MJT 19-2 Full OK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forest Partnerships Enhancing Local Livelihoods and Protecting the Environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific

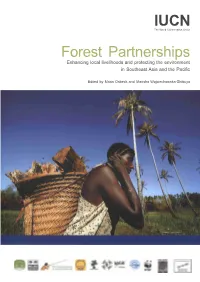

IUCN The World Conservation Union Forest Partnerships Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Edited by Maria Osbeck and Marisha Wojciechowska-Shibuya IUCN The World Conservation Union The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: The World Conservation Union (IUCN), Asia Regional Office Copyright: © 2007 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Osbeck, M., Wojciechowska-Shibuya, M. (Eds) (2007). Forest Partnerships. Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. IUCN, Bangkok, Thailand. 48pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1011-2 Cover design by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Cover photos: Local people, Papua New Guinea. A woman transports a basketful of baked sago from a pit oven back to Rhoku village. Sago is a common subsistence crop in Papua New Guinea. Western Province, Papua New Guinea. December 2004 CREDIT: © Brent Stirton / Getty Images / WWF-UK Layout by: Michael Dougherty Produced by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Printed by: Clung Wicha Press Co., Ltd. -

Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context 2

Humble: Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context 2 GRAEME J. HUMBLE Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context We had just finished our weekly shopping in a major grocery store in the city of Lae, Papua New Guinea (PNG). The young female clerk at the checkout had scanned all our items but for some reason the EFTPOS ma- chine would not accept payment from my bank’s debit card. After repeat- edly swiping my card, she jokingly quipped that sanguma (sorcery) must be causing the problem. Evidently the electronic connection between our bank and the store’s EFTPOS terminal was down, so we made alternative payment arrangements, collected our groceries, and went on our way. On reflection, the checkout clerk’s apparently flippant comment indi- cated that a supernatural perspective of causality was deeply embedded in her world view. She echoed her wider society’s “existing beliefs among Melanesians that there was always a connection between the physical and the spiritual, especially in the area of causality” (Longgar 2009:317). In her reality, her belief in the relationship between the supernatural and life’s events was not merely embedded in her world view, it was, in fact, integral to her world view. Darrell Whiteman noted that “Melanesian epistemology is essentially religious. Melanesians . do not live in a compartmentalized world of secular and spiritual domains, but have an integrated world view, in which physical and spiritual realities dovetail. Melanesians are a very religious people, and traditional religion played a dominant role in the affairs of men and permeated the life of the commu- nity” (Whiteman 1983:64, cited in Longgar 2009:317). -

Anthropology, Missiological Anthropology. the Relationship

Anthropology, Missiological Anthropology Anthropology, Missiological Anthropology. sions, where Willoughby taught from 1919 and The relationship between anthropology and Smith lectured from 1939 to 1943, little was world missions has been a long and profitable done to provide anthropological instruction for one with the benefits flowing both ways. Though missionaries before World War II. Wheaton Col- for philosophical reasons recent generations of lege (Illinois) had begun an anthropology depart- anthropologists have tended to be very critical of ment, and the WYCLIFFE BIBLE TRANSLATORS’ Sum- missionaries, much of the data used by profes- mer Institute of Linguistics, though primarily sional anthropologists from earliest days has focused on LINGUISTICS, was serving to alert come from missionaries. Anthropological pio- many to the need to take culture seriously. neers such as E. B. Tylor (1832–1917) and J. G. Though Gordon Hedderly Smith had pub- Frazer (1854–1954) in England, L. H. Morgan lished The Missionary and Anthropology in 1945, (1818–82) in the United States, and Wilhelm it was EUGENE NIDA who sparked the movement Schmidt (1868–1954) in Austria were greatly in- to make anthropology a major component in debted to missionaries for the data from which missionary thinking. He used his position as sec- they constructed their theories. Such early an- retary for translations of the American Bible So- thropological pioneers as R. H. Codrington (1830– ciety to demonstrate to missionaries and their 1922), Lorimer Fison (1832–1907), Diedrich Wes- leaders the value of anthropological insight. His termann (1875–1956), H. A. Junod (1863–1934), lectures on anthropological topics in the 1940s and Edwin Smith (1876–1957) were missionaries and early 1950s, published as Customs and Cul- for part or all of their careers. -

Boats to Burn: Bajo Fishing Activity in the Australian Fishing Zone

Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph 2 BOATS TO BURN: BAJO FISHING ACTIVITY IN THE AUSTRALIAN FISHING ZONE Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph 2 BOATS TO BURN: BAJO FISHING ACTIVITY IN THE AUSTRALIAN FISHING ZONE Natasha Stacey Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/boats_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Stacey, Natasha. Boats to burn: Bajo fishing activity in the Australian fishing zone. Bibliography. ISBN 9781920942946 (pbk.) ISBN 9781920942953 (online) 1. Bajau (Southeast Asian people) - Fishing. 2. Territorial waters - Australia. 3. Fishery law and legislation - Australia. 4. Bajau (Southeast Asian people) - Social life and customs. I. Title. (Series: Asia-Pacific environment monograph; 2). 305.8992 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Duncan Beard. Cover photographs: Natasha Stacey. This edition © 2007 ANU E Press Table of Contents Foreword xi Acknowledgments xv Abbreviations xix 1. Contested Rights of Access 1 2. Bajo Settlement History 7 3. The Maritime World of the Bajo 31 4. Bajo Voyages to the Timor Sea 57 5. Australian Maritime Expansion 83 6. Bajo Responses to Australian Policy 117 7. Sailing, Fishing and Trading in 1994 135 8. An Evaluation of Australian Policy 171 Appendix A. Sources on Indonesian Fishing in Australian Waters 195 Appendix B. Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of Australia and the Government of the Republic of Indonesia Regarding the Operations of Indonesian Traditional Fishermen in Areas of the Australian Exclusive Fishing Zone and Continental Shelf (7 November 1974) 197 Appendix C. -

Remembering Don Richardson

MISSION FRONTIERS MAR/APR 2019 Remembering Don Richardson June 23, 1935–December 23, 2018 Tribute to a Pioneer Missionary, Author & Great Commission Statesman runner all his life, missionary influencer and Don’s third book, Eternity in Their Hearts, documented pace-setter Don Richardson completed his life’s how the concept of a supreme God has existed for centuries race in Orlando, Florida, ten months after his in hundreds of cultures around the world. The book soon diagnosis with brain cancer. became “required reading” in seminaries and Bible colleges. A Christians worldwide were inspired afresh by the notion The oldest of four boys, Don spent his early years in that God has “prepared the gospel for the world,” and “the Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. His father moved world for the gospel.” the family to Victoria, British Columbia, in the hopes of securing a more promising future for them, before his own In 1977 Don began serving as World Team’s minister- death to Hodgkin’s disease when Don was 11. Don’s life at-large, speaking at dozens of events each year in North direction was set as a teen when he gave his life to Christ at America and worldwide. The Richardsons moved to a 1952 Youth for Christ rally. He subsequently met Carol Pasadena, CA, joining Ralph and Roberta Winter to assist Joy Soderstrom while training for ministry at Prairie Bible in the founding of the U.S. Center for World Mission. With Institute in Alberta. They were lovingly married for 43 the emergence of the “Perspectives on the World Christian years until her death in 2004. -

01-14.Qxp 5.5 X 8.5 Starter 5/23/13 8:53 AM Page 1 Don Richardson, Peace Child Bethany House, a Division of Baker Publishing

01-14.qxp_5.5 x 8.5 starter 5/23/13 8:53 AM Page 1 5 Don Richardson, Peace Child Bethany House, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2005. Used by permission. 01-14_5.indd 16 7/23/14 1:20 PM © 2005 by Don Richardson Published by Bethany House Publishers 11400 Hampshire Avenue South Bloomington, Minnesota 55438 www.bethanyhouse.com Bethany House Publishers is a division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan Bethany House edition published 2014 ISBN 978-0-7642-1561-2 Third Edition, 1976 Fourth Edition, 2005 Previously published by Regal Books Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. The Library of Congress has cataloged the original edition as follows: Richardson, Don. Peace child / Don Richardson.—4th ed. p. cm. ISBN 0-8307-3784-7 (trade paper) 1. Sawi (Indonesian people)—Missions. I. Title. BV3373.S3R5 2005 266’.009951—dc22 2005013901 Photos on pages 236 and 238 by Don Richardson. Other photos by Fred Roberts. Readers interested in assisting World Team’s international work force in their spiritual, medical and educational labors in developing countries should contact: World Team 1431 Stuckert Rd. P.O. Box 217, Ringwood East Warrington, PA 18976 Victoria, 3135 U.S.A. Australia 7570 Danbro Cr. www.worldteam.org Mississauga, ON L5N 6P9 Canada 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 Don Richardson, Peace Child Bethany House, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2005. -

Adopt-A-People. It Is Difficult to Sustain A

AIDS and Mission Adopt-a-People. It is difficult to sustain a mis- birth has declined—to 37 years in Uganda, for sion focus on the billions of people in the world example, the lowest global life expectancy. By or even on the multitudes of languages and cul- 2010 a decline of 25 years in life expectancy is tures in a given country. Adopt-a-people is a mis- predicted for a number of African and Asian sion mobilization strategy that helps Christians countries. In Zimbabwe it could reduce life ex- get connected with a specific group of people pectancy from 70 to 40 years in the next 15 who are in spiritual need. It focuses on the goal years. Sub-saharan Africa, with less than 10 per- of discipling a particular people group (see PEO- cent of the world’s population, has 70 percent of PLES, PEOPLE GROUPS), and sees the sending of the world’s population infected with HIV. missionaries as one of the important means to Asia, the world’s most populous region, is fulfill that goal. poised as the next epicenter of the epidemic. Ini- Adopt-a-people was conceptualized to help tially spread in the region primarily by drug in- congregations focus on a specific aspect of the jection and men having sex with men, heterosex- GREAT COMMISSION. It facilitates the visualization ual transmission is now the primary cause of of the real needs of other people groups, enables infection. It is expected that child mortality in the realization of tangible accomplishments, de- Thailand, where the sex-tourism industry has fu- velops and sustains involvement, and encourages eled the epidemic, will triple in the next 15 years more meaningful and focused prayer. -

A New Classification of Indonesia's

A New Classification of Indonesia’s Ethnic Groups (Based on the 2010 Population Census) ISEAS Working Paper #1 2014 By: Aris Ananta Nur Budi Handayani Email: [email protected] Senior Research Fellow, ISEAS Researcher Statistics-Indonesia Evi Nurvidya Arifin (BPS) Visiting Fellow, ISEAS Agus Pramono M Sairi Hasbullah Researcher Head Statistics-Indonesia Statistics-Indonesia (BPS) (BPS) Province of East Java Province of East Java 1 The ISEAS Working Paper Series is published electronically by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each Working Paper. Papers in this series are preliminary in nature and are intended to stimulate discussion and criti- cal comment. The Editorial Committee accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed, which rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be produced in any form without permission. Comments are welcomed and may be sent to the author(s) Citations of this electronic publication should be made in the following manner: Author(s), “Title,” ISEAS Working Paper on “…”, No. #, Date, www.iseas.edu.sg Series Chairman Tan Chin Tiong Series Editor Lee Hock Guan Editorial Committee Ooi Kee Beng Daljit Singh Terence Chong Francis E. Hutchinson Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30, Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Homepage: www.iseas.edu.sg Introduction For the first time since achieving independence in 1945, data on Indonesia’s ethnicity was col- lected in the 2000 Population Census. The chance to understand ethnicity in Indonesia was fur- ther enhanced with the availability of the 2010 census which includes a very rich and complicated ethnic data set. -

Community Focused Investments to Address Deforestation and Forest Degradation Project

Safeguards Due Diligence Report Project Number: 47084-002 March 2021 Indonesia: Community Focused Investments to Address Deforestation and Forest Degradation Project For Sintang and Kapuas Hulu districts, West Kalimantan Province Prepared by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry for the Asian Development Bank. This safeguards due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ABBREVIATION ADB Asian Development Bank ANR Assisted Natural Regeneration BPHP Balai Pengelolaan Hutan Produksi BPSKL Balai Perhutanan Sosial dan Kemitraan Lingkungan CBE Community Based Ecotourism CBFM Community Based Forest Management EA Executing Agency FIP Forest Investment Program FMU Forest Management Unit GRM Grievance Redress Mechanisms IP Indigenous People IPP Indigenous People Plan KMHA Kesatuan Masyarakat Adat M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MHA Masyarakat Hukum Adat MoEF Ministry of Environment and Forestry NTFP Non-Timber Forest Product PCU Project Coordinator Unit PDD Project Design Document PJLHK Pemanfaatan Jasa lingkungan Hutan Konservasi PMU Project Management Unit PISU Project Implementation Supporting Unit Poskedes Pos Kesehatan Desa Posyandu Pos Pelayanan Terpadu PTHI PT Hatfield Indonesia REDD+ Reducing Emission from Deforestation and Forest Degradation SFM Sustainable Forest Management ToR Terms of Reference TNBKDS Taman Nasional Betung Kerihun dan Danau Sentarum CONTENTS Abbreviations i Contents ii List of Tables iii List of Figures v List of Appendix vi CHAPTER I: BACKGROUND AND PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 1. -

An Indigenous Agricultural Model from West Sumatra: a Source of Scientific Insight

Agricultural Systems 26 (1988) 191-209 An Indigenous Agricultural Model from West Sumatra: A Source of Scientific Insight Carol J. Pierce Colfer* Department of' Agronomy and Soils, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA Dan W. Gill Soil Science Department, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27650, USA & Fahmuddin Agus Centre for Soils Research. Ji. Juanda 98, Bogor, Indonesia (Received 22 June 1987, accepted 27 July 1987) SUMMARY A long-c vcled, rice andrubber basedswidden system was investigatedamong the Minangkabau of Pulai. West Sumatra, in 1985-86, as part of the Tropsoils Project. This paperfirst describesthe conceptualframework used by- these people with regardto their land. The production and income that derive from their diverse agricultural activities are then discussed. Our conclusions are that (1) tree crops can be effectively and beneficially incorporatedinto a system that includes food crops, (2) diversifiedsystems make sense in these high risk environments and (3) both sexes areimportant in this kind of agriculture. We urge scientists to broaden their traditional researchparadigmso as to incorporateand improve on systems like the one describedhere. INTRODUCTION Agricultural research in the Humid Tropics has been conducted, by and large, using a conceptual model which assumes land scarcity, field crops, and . Present address: Ministry of Agriculture, DG Fisheries, MSFC, PO Box 467, Muscat, Oman. 191 Agricultural Systems 0308-521X/88/$03.50 () Elsevier Applied Science Publishers Ltd, England, 1988. Printed in Great Britain / 192 Carol J. Pierce Colfer, Dan W. Gill, Fahinuddin Agus labour intensive management by men. Recently, there has been some recognition that this model is, in many ways, inappropriate to the marginal, unirrigated upland areas where we are beginning Io work (e.g. -

FULL ISSUE (48 Pp., 2.2 MB PDF)

Vol. 7, No.4 nternattona• October 1983 ettn• Toward N ell' Priorities in Mission hristians today are challenged to take a closer look at In the midst of both perplexity and opportunity, Christians Ctheir priorities. When it comes to mission, do our actions are continually challenged to pay closer attention to their priori genuinely reflect what we say our goals are? Have we paid suffi ties. cient attention to what our priorities are, and what they ought to be? There is ample biblical encouragement for us to rethink our priorities periodically, and this issue of the International Bulletin On Page challenges us to do just that. David B. Barrett, editor of the World Christian Encyclopedia, con tends that priorities for Christian goals have been greatly distorted by the ways in which Christians actually spend their money. He 146 Silver and Gold Have I None: Church of the Poor or provides here statistical data to examine the financial resources Church of the Rich? that are available to Christians in the pursuit of their mission, and DavidB. Barrett he suggests strategies for improvement. Vinay Samuel and Chris Sugden call attention to the ways in 152 Mission Agencies as Multinationals which the operations of mission agencies resemble multinational Vinay Samuel and Chris Sugden corporations, and distort the priorities of national churches. In re 156 Responses to the Article by Vinay Samuel and Chris sponse, William R. Burrows, S.V.D., and David M. Howard ac Sugden knowledge the problem, and assess its implications for mission William R. Burrows, S. ~D. and DavidM Howard planning. -

2 the Trans New Guinea Family Andrew Pawley and Harald Hammarström

2 The Trans New Guinea family Andrew Pawley and Harald Hammarström 2.1 Introduction The island of New Guinea is a region of spectacular, deep linguistic diversity.1 It contains roughly 850 languages, which on present evidence fall into at least 18 language families that are not demonstrably related, along with several iso- lates.2 This immense diversity, far greater than that found in the much larger area of Europe, is no doubt mainly a consequence of the fact that New Guinea has been occupied for roughly 50,000 years by peoples organised into small kin-based social groups, lacking overarching political affiliations, and dispersed across a terrain largely dominated by rugged mountains and swampy lowlands, with quite frequent population movements. Among the non-Austronesian families of New Guinea one family stands out for its large membership and wide geographic spread: Trans New Guinea (TNG). With a probable membership of between 300 and 500 discrete languages, plus hundreds of highly divergent dialects, TNG is among the most numerous of the world’s language families.3 TNG languages are spoken from the Bomberai Pen- insula at the western end of mainland New Guinea (132 degrees E) almost to the eastern tip of the island (150 degrees E). Most of the cordillera that runs for more than 2000 kilometers along the centre of New Guinea is occupied exclusively by TNG languages. They are also prominent in much of the lowlands to the south of the cordillera and in patches to the north, especially from central Madang Province eastwards. There are possible outliers spoken on Timor, Alor and Pantar.