Adopt-A-People. It Is Difficult to Sustain A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kingdom Partnerships for Synergy in Missions

Kingdom Partnerships for Synergy in Missions William D. Taylor, Editor William Carey Library Pasadena, California, USA Editor: William D. Taylor Technical Editor: Susan Peterson Cover Design: Jeff Northway © 1994 World Evangelical Fellowship Missions Commission All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo- copying and recording, for any purpose, without the express written consent of the publisher. Published by: William Carey Library P.O. Box 40129 Pasadena, CA 91114 USA Telephone: (818) 798-0819 ISBN 0-87808-249-2 Printed in the United States of America Table of Contents Preface Michael Griffiths . vii The World Evangelical Fellowship Missions Commission William D. Taylor . xiii 1 Introduction: Setting the Partnership Stage William D. Taylor . 1 PART ONE: FOUNDATIONS OF PARTNERSHIP 2 Kingdom Partnerships in the 90s: Is There a New Way Forward? Phillip Butler . 9 3 Responding to Butler: Mission in Partnership R. Theodore Srinivasagam . 31 4 Responding to Butler: Reflections From Europe Stanley Davies . 43 PART TWO: CRITICAL ISSUES IN PARTNERSHIPS 5 Cultural Issues in Partnership in Mission Patrick Sookhdeo . 49 6 A North American Response to Patrick Sookhdeo Paul McKaughan . 67 7 A Nigerian Response to Patrick Sookhdeo Maikudi Kure . 89 8 A Latin American Response to Patrick Sookhdeo Federico Bertuzzi . 93 9 Control in Church/Missions Relationship and Partnership Jun Vencer . 101 10 Confidence Factors: Accountability in Christian Partnerships Alexandre Araujo . 119 iii PART THREE: INTERNATIONALIZING AGENCIES 11 Challenges of Partnership: Interserves History, Positives and Negatives James Tebbe and Robin Thomson . 131 12 Internationalizing Agency Membership as a Model of Partnership Ronald Wiebe . -

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

Northwest Friend, September 1959

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church Northwest Friend (Quakers) 9-1959 Northwest Friend, September 1959 George Fox University Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_nwfriend Recommended Citation George Fox University Archives, "Northwest Friend, September 1959" (1959). Northwest Friend. 186. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_nwfriend/186 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church (Quakers) at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwest Friend by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Left to right: Dean Gregory, General Superintendent of Oregon Yearly Meeting; Keith Sarver, General Superintendent of California Yearly Meeting and recent guest speaker for our yearly meeting sessions; Dorwin E. Smith, presiding clerk. //i ^ .The^ Irish Quakers used a verb in their letter of greeting to the e«E^ngelical Friends Conference that could be useful in Oregon Yearly COUNT down... ^ Meeting: "May your meetings be presenced by the Spirit of the Lord." a travelogue of Gerald Dillon's trip yWhen this happens it is an impressive and fearful thing. The first announcement of God's redemptive intention toward mankind was made "We're off . it's just 11:40 p.m.," ob to a man and a woman hiding in mortal fear from the presence of the Lord. The Law of God was given to a man trembling in terror amid fire served Everett Heacock, as together we started a journey around the world. -

A Brief Survey of Missions

2 A Brief Survey of Missions A BRIEF SURVEY OF MISSIONS Examining the Founding, Extension, and Continuing Work of Telling the Good News, Nurturing Converts, and Planting Churches Rev. Morris McDonald, D.D. Field Representative of the Presbyterian Missionary Union an agency of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA P O Box 160070 Nashville, TN, 37216 Email: [email protected] Ph: 615-228-4465 Far Eastern Bible College Press Singapore, 1999 3 A Brief Survey of Missions © 1999 by Morris McDonald Photos and certain quotations from 18th and 19th century missionaries taken from JERUSALEM TO IRIAN JAYA by Ruth Tucker, copyright 1983, the Zondervan Corporation. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, MI Published by Far Eastern Bible College Press 9A Gilstead Road, Singapore 309063 Republic of Singapore ISBN: 981-04-1458-7 Cover Design by Charles Seet. 4 A Brief Survey of Missions Preface This brief yet comprehensive survey of Missions, from the day sin came into the world to its whirling now head on into the Third Millennium is a text book prepared specially by Dr Morris McDonald for Far Eastern Bible College. It is used for instruction of her students at the annual Vacation Bible College, 1999. Dr Morris McDonald, being the Director of the Presbyterian Missionary Union of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA, is well qualified to write this book. It serves also as a ready handbook to pastors, teachers and missionaries, and all who have an interest in missions. May the reading of this book by the general Christian public stir up both old and young, man and woman, to play some part in hastening the preaching of the Gospel to the ends of the earth before the return of our Saviour (Matthew 24:14) Even so, come Lord Jesus Timothy Tow O Zion, Haste O Zion, haste, thy mission high fulfilling, to tell to all the world that God is Light; that He who made all nations is not willing one soul should perish, lost in shades of night. -

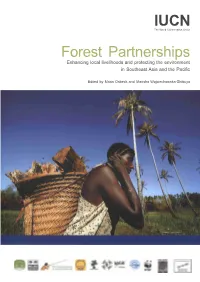

Forest Partnerships Enhancing Local Livelihoods and Protecting the Environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific

IUCN The World Conservation Union Forest Partnerships Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Edited by Maria Osbeck and Marisha Wojciechowska-Shibuya IUCN The World Conservation Union The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: The World Conservation Union (IUCN), Asia Regional Office Copyright: © 2007 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Osbeck, M., Wojciechowska-Shibuya, M. (Eds) (2007). Forest Partnerships. Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. IUCN, Bangkok, Thailand. 48pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1011-2 Cover design by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Cover photos: Local people, Papua New Guinea. A woman transports a basketful of baked sago from a pit oven back to Rhoku village. Sago is a common subsistence crop in Papua New Guinea. Western Province, Papua New Guinea. December 2004 CREDIT: © Brent Stirton / Getty Images / WWF-UK Layout by: Michael Dougherty Produced by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Printed by: Clung Wicha Press Co., Ltd. -

Avoiding the Tentmaker Trap

AVOIDING THE TENTMAKER TRAP A special edition for the Bedouin CD Not to be copied in any way This book was re-edited in 1997 and printed by WEC International. Second printing 1999, Third Printing 2002. To obtain the latest version with up-to-date appendicies etc., please contact WEC International Dan Gibson 2002 1 Chapter One Tom and Sue (A case study) Tom and Sue were excited. Their interest in missions had been growing for several years now and finally the pieces were falling together. Several weeks back Tom responded to an advert in a professional journal for a position in the Middle East and the reply was positive. The company wanted them in two weeks time! At first they were taken back by the suddenness of it all, but the company was adamant that they must come in two weeks or else someone else would fill the position. They spent a long evening together discussing the pro's and cons. Tom would have to quit his job at the plant. Sue would need to leave her work at the flower shop. It would mean leaving their church and close friends. That much seemed normal, although a little frightening. They had grown used to the security that comes from a steady job, income and the support of their church. But Sue was excited about the possibilities of missions. The more they discussed it the more excited they got. First of all they wouldn't have to join a mission organization. They were painfully aware of a young couple from their church who had spent several years trying to raise enough support for missions and then had fallen short and were now trying to sort their lives out. -

International Bulletin of Missionary Research, Vol 36, No. 3

Vol. 36, No. 3 July 2012 Faith, Flags, and Identities n March 24–25, 2011, Duke Divinity School, Durham, ONorth Carolina, hosted a two-day conference focused on the somewhat cumbersome theme “Saving the World? The On Page Changing Terrain of American Protestant Missions, 1910 to the 115 Change and Continuity in American Protestant Present” (see http://isae.wheaton.edu/projects/missions). Orga- Foreign Missions nized and sponsored by Wheaton College’s Institute for the Study Edith L. Blumhofer of American Evangelicals, the conference involved nearly one hundred academ- 115 The Presbyterian Church in Canada’s Mission ics, who presented to Canada’s Native Peoples, 1900–2000 and listened to Peter Bush papers and lec- 122 Pentecostal Missions and the Changing tures exploring the Character of Global Christianity evolving nature of Heather D. Curtis American Protes- The Sister Church Phenomenon: A Case Study tant missions since 129 of the Restructuring of American Christianity the Edinburgh Against the Backdrop of Globalization World Mission- ary Conference of Janel Kragt Bakker 1910, and who dis- 136 Changes in African American Mission: cussed the nation’s Rediscovering African Roots Courtesy of Affordable Creations, http://peggymunday.blogspot.com continuing influ- Mark Ellingsen ence on Christianity globally. This issue of the journal is pleased to 138 Noteworthy feature five of the papers presented at this conference. “Americans,” the late Tony Judt observed, “have trouble 143 The Wesleys of Blessed Memory: Hagiography, with the idea that they are not the world’s most heroic warriors Missions, and the Study of World Methodism or that their soldiers have not fought harder and died braver Jason E. -

Fazio | 1 Presented at the Council on Dispensational Hermeneutics

F a z i o | 1 Presented at the Council on Dispensational Hermeneutics September 18-19, 2019 – Calvary University, Belton, Missouri Dispensational Thought as Motivation for Social Activism among Early Plymouth Brethren James I. Fazio Introduction Over the past two centuries, the community of Christians known as the Plymouth Brethren have been known for several traits that stem from a strict adherence to a theologically conservative view of Scripture’s authority and sufficiency as understood through a literalistic interpretation. This approach to Scripture has resulted in an orientation that could be generally described as evangelical, if not fundamentalist, with several nuances, including a primitivist ecclesiology that maintains a low church orientation, a premillennial eschatology that is consistent with a dispensational understanding of Scripture, and a Calvinistic soteriology that emphasizes separatism from the world and other corrupting influences. It may also be added that the Brethren have become as well defined by what they stand against as what they stand for. In this way, they may be well characterized as anti-denominational, anti-creedal, anti-liturgical, and anti-clerical. Many of these named qualities are commonly recognized by those who possess even a scant familiarity with those who identify with the label Brethren. What is less immediately recognized is that among the most prominent contributions made by this community of dispensational-minded believers is the indelible mark they have left on the developing world through their unrivaled efforts in international and cross-cultural missionary outreach and a distinct zeal for social activism. F a z i o | 2 Some may be aware of the itinerate ministry of John Nelson Darby (1800–1882) in Switzerland, throughout Europe, and in North America, including his original translation work of the Hebrew and Greek Testaments into English, French, and German. -

Contents El Paso TX 79915

IJFM (ISSN # 0743-2529) was estab- INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF lished in 1984 by the International Student Leaders Coalition for Frontier FRONTIER MISSIONS Missions. Published quarterly for $15.00 in Jan.- Jan.-March 1996 March., April-June, July-Sept. and Oct.- Volume 13 Number 1 Dec., by the International Journal of Frontier Missions, 7665 Wenda Way, Contents El Paso TX 79915. Editor: 1 Editorial: Shoring up the Foundations Hans M. Weerstra Hans M. Weerstra Associate Editors: Richard A. Cotton 3 The Great Commission in the Old Testament D. Bruce Graham Walter C. Kaiser, Jr. Managing Editor: Judy L. Weerstra 9 The Khmer: A People Disillusioned Assistant to the Editor: Adopt-A-People Clearinghouse Kelly Cordova IJFM Secretary: 11 All the Clans, All the Peoples Barbara R. Pitts Richard Showalter Publisher: Bradley Gill 15 The Supremacy of God Among “All the Nations” John Piper The IJFM promotes the investigation of frontier mission issues, including plans and coordination for world evangeliza- 27 Challenging the Church to World Mission tion, measuring and monitoring its David J. Hesselgrave progress, defining, publishing and profiling unreached peoples, and the promotion of biblical mission theology. 33 Biblical Foundations for Missions: Seven Clear Lessons The Journal advocates completion of Thomas Schirrmacher world evangelization by AD 2000. The IJFM also seeks to promote inter- 41 Seeing the Big Picture generational dialogue between senior Ralph D. Winter and junior mission leaders, cultivate an international fraternity of thought in the development of frontier missiology. 45 Melchizedek and Abraham Walk Together in World Mission W. Douglas Smith, Jr. Address all editorial correspondence and manuscripts, to 7665 Wenda Way, El Paso Texas, 79915 USA. -

You Have Access to This Because You Are an EMQ Subscriber. Not to Be Reproduced, Reprinted, Or Redistributed Without Prior Consent from EMQ

You have access to this because you are an EMQ subscriber. Not to be reproduced, reprinted, or redistributed without prior consent from EMQ. For permissions, email [email protected]. word from the editor eadership is critical in every human endeavor. This includes not only leading, but the ability to L pass leadership on—whether to local Christians or to the next generation. Some components of Chris- A. Scott Moreau tian leadership development are universal, such as the Editor memorization of Scripture. Others are framed in terms of the values of the society in which we serve; issues of honor, trust, patronage, personal care, money and leadership training all happen in particular settings drawing on particular values. In this issue, our authors map some of the terrain of these values, helping us understand them better and see them in light of the particular settings in which the authors serve. We hope you will be encouraged, and challenged, as you read them and learn to draw on their insights for your ministry setting. All of the articles in this issue of EMQ are available in reprint format Perspective: The Not-So-Good Method of Church Planting. page 6 A Second Look: What Are We to Do? A Question of Self-defense . page 10 Memorization and Maturation . page 12 Good Decisions Need a Godly Process: Acts 15 as Our Guide . page 18 A Japanese Gospel Message . page 26 Suffering and the Widows of Kitual Village (Kenya) . page 36 The Priority of Leadership Training in Global Mission . page 44 Resourcing Majority World Seminaries: A Case Study from Indonesia . -

Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context 2

Humble: Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context 2 GRAEME J. HUMBLE Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context We had just finished our weekly shopping in a major grocery store in the city of Lae, Papua New Guinea (PNG). The young female clerk at the checkout had scanned all our items but for some reason the EFTPOS ma- chine would not accept payment from my bank’s debit card. After repeat- edly swiping my card, she jokingly quipped that sanguma (sorcery) must be causing the problem. Evidently the electronic connection between our bank and the store’s EFTPOS terminal was down, so we made alternative payment arrangements, collected our groceries, and went on our way. On reflection, the checkout clerk’s apparently flippant comment indi- cated that a supernatural perspective of causality was deeply embedded in her world view. She echoed her wider society’s “existing beliefs among Melanesians that there was always a connection between the physical and the spiritual, especially in the area of causality” (Longgar 2009:317). In her reality, her belief in the relationship between the supernatural and life’s events was not merely embedded in her world view, it was, in fact, integral to her world view. Darrell Whiteman noted that “Melanesian epistemology is essentially religious. Melanesians . do not live in a compartmentalized world of secular and spiritual domains, but have an integrated world view, in which physical and spiritual realities dovetail. Melanesians are a very religious people, and traditional religion played a dominant role in the affairs of men and permeated the life of the commu- nity” (Whiteman 1983:64, cited in Longgar 2009:317). -

The Consummation: the Crucial Ministries Involved

The Consummation: The Crucial Ministries Involved Reaching the peoples of the 10/40 Window has been greatly advanced by a variety of support and media ministries. Immense efforts are being poured into these ministries, all of which have the potential of completely covering the world’s population and peoples. In this article the author briefly describes the impact of the major mega-ministries working to help reach the unreached peoples of the world. by Patrick Johnstone an we really see church planting believers in a small tribe of 1,000 can Translating the C initiatives launched for all peo- be significant, but one church among Scriptures ples within our present generation? the 6 million Tibetans or a few It is almost impossible to conceive Some might question that. In answer I churches among the 200 million Ben- of a strong church within a people report on what transpired in GCOWE- galis is less than a drop in the bucket. that has no word of the Bible trans- 97 in South Korea. Our aim should be at minimum a lated into their own language. The Luis Bush, the Director of the church for every people, but this is lack of the Scriptures for the Berber AD2000 Mvt., made a great effort dur- only a beginning. This is where the languages of North Africa was a signif- ing GCOWE-97to encourage mission Discipline a Whole Nation vision of icant factor in the surprising disap- agencies represented and the various Jim Montgomery is so valid. We need pearance of the once-large North Afri- national delegations to commit them- to ensure that there is a vital, wor- can Church between the coming of selves to reaching each of the remain- shiping group of believers within easy Islam in 698 and the twelfth century.