Abolitionist Movement. the Abolitionist Move- Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scripture Translations in Kenya

/ / SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA by DOUGLAS WANJOHI (WARUTA A thesis submitted in part fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in the University of Nairobi 1975 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY Tills thesis is my original work and has not been presented ior a degree in any other University* This thesis has been submitted lor examination with my approval as University supervisor* - 3- SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA CONTENTS p. 3 PREFACE p. 4 Chapter I p. 8 GENERAL REASONS FOR THE TRANSLATION OF SCRIPTURES INTO VARIOUS LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS Chapter II p. 13 THE PIONEER TRANSLATORS AND THEIR PROBLEMS Chapter III p . ) L > THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRANSLATORS AND THE BIBLE SOCIETIES Chapter IV p. 22 A GENERAL SURVEY OF SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA Chapter V p. 61 THE DISTRIBUTION OF SCRIPTURES IN KENYA Chapter VI */ p. 64 A STUDY OF FOUR LANGUAGES IN TRANSLATION Chapter VII p. 84 GENERAL RESULTS OF THE TRANSLATIONS CONCLUSIONS p. 87 NOTES p. 9 2 TABLES FOR SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN AFRICA 1800-1900 p. 98 ABBREVIATIONS p. 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY p . 106 ✓ - 4- Preface + ... This is an attempt to write the story of Scripture translations in Kenya. The story started in 1845 when J.L. Krapf, a German C.M.S. missionary, started his translations of Scriptures into Swahili, Galla and Kamba. The work of translation has since continued to go from strength to strength. There were many problems during the pioneer days. Translators did not know well enough the language into which they were to translate, nor could they get dependable help from their illiterate and semi literate converts. -

518-0002 USAID/Quito OPG Rural Community Health Dec. 82 Y R3 1 E

.I\- - - - , - CLASSIFICATION Report Contol '&A 3 PROJFCT EVALUATION SUMMARY (PES) - PART I Symbol U447 OFFICE 1. PROJECT TITLE 2.PROJECT NUMBER MISSION/AID/W 518-0002 USAID/Quito 4.EVALUATION NUMBER (Enter the number maIntalnel by the OPG Rural Community Health reporting unit e.g., Country or AID/W Admnistrative Code, Fiscal Year, Serial No. bcginning with No. 1 each FY) E0P r REGULAR EVALUATION 03 SPECIAL EVALUATION 5.KEY PROJECT IMFLEMENTATION DATES 6.ESTIMATED PROJECT 7. PERIOD COVERED BY EVALUATION A. First B. Final C. Final FUNDING Fo mnhy. C- 7 PRO-AG or Obligation Inpu t A. Total $ 800 .000 From (month/yr,) flt" 78 Eqivatni Ept Dell$r4,y0 To (month/yr.) Dec. 82 Dec. 82 - Maly R3 FY I0 FVYi-hFY_2 M B. U.S. 244,000 I__ReviewDate of Evaluation . .. y 3 8. ACTION DECISIONS APPROVED BY MISSION OR AID/W OFFICE DIRECTOR A. List decisions and/or unresolved Isues; cite those Items needing further study. 0.NAME OF 1. DATE ACTION (NOTE: Mission decisions which anticipate AID/W or regional office action should RESPONSIBLE COMPLETED specify type of document, e.g., airgram, SPAR, PIOwhich will present dtalled request.) FOR ACTION No unresolved issues. An End of Project Eva luation was carried out on Nov. 82 - March 83 as reported in following documents: a) Consultant Report - Patrick Marname, Nov. 82 on OPG-0002. ,) A PVO's Experience - End of Project Repor: by HCJB,.May 83. 9.INVENTORY OF DOCUMENTS TO BE REVISED PER ABOVE DECISIONS 10.ALTERNATIVE OECISIONS ON FUTURE OF PROJECT A. PojecT Project Paper 1 e.,IIm plemCPIentation Network Plan , Other fSpaol,¥I A. -

Best Books for Kindergarten Through High School

! ', for kindergarten through high school Revised edition of Books In, Christian Students o Bob Jones University Press ! ®I Greenville, South Carolina 29614 NOTE: The fact that materials produced by other publishers are referred to in this volume does not constitute an endorsement by Bob Jones University Press of the content or theological position of materials produced by such publishers. The position of Bob Jones Univer- sity Press, and the University itself, is well known. Any references and ancillary materials are listed as an aid to the reader and in an attempt to maintain the accepted academic standards of the pub- lishing industry. Best Books Revised edition of Books for Christian Students Compiler: Donna Hess Contributors: June Cates Wade Gladin Connie Collins Carol Goodman Stewart Custer Ronald Horton L. Gene Elliott Janice Joss Lucille Fisher Gloria Repp Edited by Debbie L. Parker Designed by Doug Young Cover designed by Ruth Ann Pearson © 1994 Bob Jones University Press Greenville, South Carolina 29614 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved ISBN 0-89084-729-0 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Contents Preface iv Kindergarten-Grade 3 1 Grade 3-Grade 6 89 Grade 6-Grade 8 117 Books for Analysis and Discussion 125 Grade 8-Grade12 129 Books for Analysis and Discussion 136 Biographies and Autobiographies 145 Guidelines for Choosing Books 157 Author and Title Index 167 c Preface "Live always in the best company when you read," said Sydney Smith, a nineteenth-century clergyman. But how does one deter- mine what is "best" when choosing books for young people? Good books, like good companions, should broaden a student's world, encourage him to appreciate what is lovely, and help him discern between truth and falsehood. -

Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives William Prevette University of Edinburgh, Ir [email protected]

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Edinburgh Centenary Series Resources for Ministry 1-1-2014 Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives William Prevette University of Edinburgh, [email protected] Keith White University of Edinburgh, [email protected] C. Rosalee Velloso da Silva University of Edinburgh, [email protected] D. J. Konz University of Edinburgh, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.csl.edu/edinburghcentenary Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Prevette, William; White, Keith; da Silva, C. Rosalee Velloso; and Konz, D. J., "Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives" (2014). Edinburgh Centenary Series. Book 24. http://scholar.csl.edu/edinburghcentenary/24 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Resources for Ministry at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Edinburgh Centenary Series by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGNUM EDINBURGH CENTENARY SERIES Volume 24 Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives REGNUM EDINBURGH CENTENARY SERIES The centenary of the World Missionary Conference of 1910, held in Edinburgh, was a suggestive moment for many people seeking direction for Christian mission in the 21st century. Several different constituencies within world Christianity held significant events around 2010. From 2005, an international group worked collaboratively to develop an intercontinental and multi- denominational project, known as Edinburgh 2010, based at New College, University of Edinburgh. This initiative brought together representatives of twenty different global Christian bodies, representing all major Christian denominations and confessions, and many different strands of mission and church life, to mark the centenary. -

Present State of Christianity, and of the Missionary Establishments For

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com PresentstateofChristianity,andthemissionaryestablishmentsforitspropagationinallpartsworld JohannHeinrichD.Zschokke,FredericShoberl,Zschokke ^SSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSt Harvard College Library FROM THE BEQUEST OF Evert Jansen Wendell CLASS OF 1882 1918 c 3. & J. TTARPER, PRINTERS, 82 FfHF ffllilBMfHr! ITT PRESS, FOR THE TRADE, PELHAM; OR THE ADVENTURES OF A GEN TLEMAN. A Novel. In 2 vols. 12mo. 14 If the most brilliant wit, a narrative whose interest never flags, and some pictures of the most rivetting interest, can make a work popular, " Pelham" will he as first rate in celebrity as it is in excellence. The scenes are laid at the present day, and in fashionable life." — London Literary Gazette. THE SUBALTERN'S LOG-BOOK ; containing anecdotes of well-known Military Characters. In two vols. 12mo. In Press, for the Trade. DOMESTIC DUTIES ; or, Instructions to young Married Ladies, on the Management of their Households and the Regulation of their Conduct in the various relations and duties of Married Life. By Mrs. William Parkes. PRESENT STATE OF CHRISTIANITY, and of the Mis sionary Establishment for its propagation in all parts of the World. Edited by Frederic Shoberl. 12ano. HISTORY OF THE CAMPAIGNS OF THE BRITISH ARMIES in Spain, Portugal, and the South op France, from 1 308 to 1 8 14. By the Author of " Cyri! Thornton." GIBBON'S ROME, with Maps, Portrait, and Vignette Ti tles. 4 vols. 8vo. CROCKFORD'S LIFE IN THE WEST ; or, THE CUR TAIN DRAWN. -

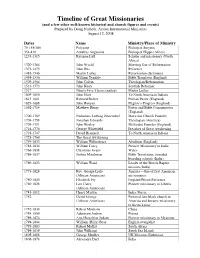

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

Octor of ^F)Ilos(Opi)P «&=• /•.'' in St EDUCATION

^ CONTRIBUTION OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONARIES TOWARDS DEVELOPMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION IN ASSAM SINCE INDEPENDENCE ABSTRACT OF THE <^ V THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF octor of ^f)ilos(opI)p «&=• /•.'' IN St EDUCATION wV", C BY •V/ SAYEEDUL HAQUE s^^ ^ 1^' UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ALI AHMAD DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2009 ^&. ABSTRACT Title of the study: "Contribution of Christian Missionaries Towards Development of Secondary Education in Assam Since Independence" Education is the core of all religions, because it prepares the heathen mind for the proper understanding and acceptance of the supremacy of his Creator. Thus, acquisition of Knowledge and learning is considered as an act of salvation in Christianity. The revelation in Bible clearly indicates that the Mission of Prophet of Christianity, Jesus Christ, is to teach his people about the tenets of Christianity and to show them the true light of God. As a true follower of Christ, it becomes the duty of every Christian to act as a Missionary of Christianity. The Missionaries took educational enterprise because they saw it as one of the most effective means of evangelization. In India, the European Missionaries were regarded as the pioneers of western education, who arrived in the country in the last phase of the fifteenth century A.D. The Portuguese Missionaries were the first, who initiated the modem system of education in India, when St. Xavier started a University near Bombay in 1575 A.D. Gradually, other Europeans such as the Dutch, the Danes, the French and the English started their educational efforts. -

In One Sacred Effort – Elements of an American Baptist Missiology

In One Sacred Effort Elements of an American Baptist Missiology by Reid S. Trulson © Reid S. Trulson Revised February, 2017 1 American Baptist International Ministries was formed over two centuries ago by Baptists in the United States who believed that God was calling them to work together “in one sacred effort” to make disciples of all nations. Organized in 1814, it is the oldest Baptist international mission agency in North America and the second oldest in the world, following the Baptist Missionary Society formed in England in 1792 to send William and Dorothy Carey to India. International Ministries currently serves more than 1,800 short- term and long-term missionaries annually, bringing U.S. and Puerto Rico churches together with partners in 74 countries in ministries that tell the good news of Jesus Christ while meeting human needs. This is a review of the missiology exemplified by American Baptist International Ministries that has both emerged from and helped to shape American Baptist life. 2 American Baptists are better understood as a movement than an institution. Whether religious or secular, movements tend to be diverse, multi-directional and innovative. To retain their character and remain true to their core purpose beyond their first generation, movements must be able to do two seemingly opposite things. They must adopt dependable procedures while adapting to changing contexts. If they lose the balance between organization and innovation, most movements tend to become rigidly institutionalized or to break apart. Baptists have experienced both. For four centuries the American Baptist movement has borne its witness within the mosaic of Christianity. -

HBU Academy – 1St Place Winner-Piece of the Past Essay Contest, 2020

HBU Academy – 1st place winner-Piece of the Past Essay Contest, 2020 A Threefold Legacy: How Adoniram Judson’s Wives Contributed to the Ministry of the Man Who First Translated the Bible for the Burmese People by Rebecca Rizzotti In a glass case in the Dunham Bible Museum sits a book, open to public eye, filled seemingly with mere curves and squiggles. To an uninformed passerby, it may appear a simple curiosity, yet there is a story of incredible suffering, perseverance, and patience behind that book. It is a Burmese Bible. Adoniram Judson, as the first missionary sent out from the United States to a foreign country and the first person to translate the Bible into Burmese, is a well-known figure in the annals of missions. Yet in the many biographies, narratives, and articles centering on his life and work, the lives and work of his three wives—especially the latter two—are often overlooked. Each woman contributed immensely to a different aspect of his service that was essential to success as a missionary. Ann Hasseltine Judson demonstrated an incredible spirit of self-sacrifice during her marriage to Adoniram—first in agreeing to leave her family and homeland for a future of sickness and suffering, just days after their wedding in 1812—but most especially during her husband’s twenty-one months in brutal Burmese prisons in 1824-1825, his punishment for the false charge of espionage as he ministered in Rangoon. She “saved Judson’s life during the prison years… several times…Ann loved him fiercely, unreservedly, even to the point of giving her life for him. -

ABSTRACT Liang Fa's Quanshi Liangyan and Its Impact on The

ABSTRACT Liang Fa’s Quanshi liangyan and Its Impact on the Taiping Movement Sukjoo Kim, Ph.D. Mentor: Rosalie Beck, Ph.D. Scholars of the Taiping Movement have assumed that Liang Fa’s Quanshi liangyan 勸世良言 (Good Words to Admonish the Age, being Nine Miscellaneous Christian Tracts) greatly influenced Hong Xiuquan, but very little has been written on the role of Liang’s work. The main reason is that even though hundreds of copies were distributed in the early nineteenth century, only four survived the destruction which followed the failure of the Taiping Movement. This dissertation therefore explores the extent of the Christian influence of Liang’s nine tracts on Hong and the Taiping Movement. This study begins with an introduction to China in the nineteenth century and the early missions of western countries in China. The second chapter focuses on the life and work of Liang. His religious background was in Confucianism and Buddhism, but when he encountered Robert Morrison and William Milne, he identified with Christianity. The third chapter discusses the story of Hong especially examining Hong’s acquisition of Liang’s Quanshi liangyan and Hong’s revelatory dream, both of which serve as motives for the establishment of the Society of God Worshippers and the Taiping Movement. The fourth chapter develops Liang’s key ideas from his Quanshi liangyan and compares them with Hong’s beliefs, as found in official documents of the Taipings. The fifth chapter describes Hong’s beliefs and the actual practices of the Taiping Movement and compares them with Liang’s key ideas. -

The Images of Jesus in the Emergence of Christian Spirituality in Ming and Qing China

religions Article The Images of Jesus in the Emergence of Christian Spirituality in Ming and Qing China Xiaobai Chu Department of Chinese Language and Literature, East China Normal University, 500 Dongchuan Rd., Shanghai 200241, China; [email protected]; Tel.: +86-135-6419-6708 Academic Editor: Mark G. Toulouse Received: 10 January 2016; Accepted: 15 March 2016; Published: 18 March 2016 Abstract: Images of Jesus Christ played an important role in the emergence of Christian spirituality in Ming and Qing China. Of the great many images that we know from this period, this paper introduces five of them: Jesus as infant, criminal, gate, brother, and pig. The paper unfolds the historical, anthropological, and theological layers of these images to reveal the original tension between Christian spirituality and Chinese culture. The central thesis of the paper therefore is that this tension is reflected in the images of Jesus Christ and, moreover, that analyzing this tension allows us to achieve a more profound understanding of the emergence of Christian spirituality in Ming, Qing, and perhaps even today’s China. Keywords: Image of Jesus Christ; Christian spirituality; missionary practice; local knowledge; Chinese cultural memory 1. Introduction What would you think upon seeing Jesus depicted as a Chinese, more specifically, as a Confucius teacher? At least to Western people with no particular knowledge of Christian history, such an image would likely appear strange. Was this how Chinese people reacted to images of Jesus Christ that were presented to them in the long history of Christian missions in China? What was the image Chinese people themselves made of Jesus Christ’s person? These are but a few basic questions that we can ask about the images of Jesus Christ that circulated in Ming and Qing China. -

A Brief Survey of Missions

2 A Brief Survey of Missions A BRIEF SURVEY OF MISSIONS Examining the Founding, Extension, and Continuing Work of Telling the Good News, Nurturing Converts, and Planting Churches Rev. Morris McDonald, D.D. Field Representative of the Presbyterian Missionary Union an agency of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA P O Box 160070 Nashville, TN, 37216 Email: [email protected] Ph: 615-228-4465 Far Eastern Bible College Press Singapore, 1999 3 A Brief Survey of Missions © 1999 by Morris McDonald Photos and certain quotations from 18th and 19th century missionaries taken from JERUSALEM TO IRIAN JAYA by Ruth Tucker, copyright 1983, the Zondervan Corporation. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, MI Published by Far Eastern Bible College Press 9A Gilstead Road, Singapore 309063 Republic of Singapore ISBN: 981-04-1458-7 Cover Design by Charles Seet. 4 A Brief Survey of Missions Preface This brief yet comprehensive survey of Missions, from the day sin came into the world to its whirling now head on into the Third Millennium is a text book prepared specially by Dr Morris McDonald for Far Eastern Bible College. It is used for instruction of her students at the annual Vacation Bible College, 1999. Dr Morris McDonald, being the Director of the Presbyterian Missionary Union of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA, is well qualified to write this book. It serves also as a ready handbook to pastors, teachers and missionaries, and all who have an interest in missions. May the reading of this book by the general Christian public stir up both old and young, man and woman, to play some part in hastening the preaching of the Gospel to the ends of the earth before the return of our Saviour (Matthew 24:14) Even so, come Lord Jesus Timothy Tow O Zion, Haste O Zion, haste, thy mission high fulfilling, to tell to all the world that God is Light; that He who made all nations is not willing one soul should perish, lost in shades of night.