Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing the Witch in Contemporary American Popular Culture

"SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES": CONSTRUCTING THE WITCH IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE Catherine Armetta Shufelt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2007 Committee: Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor Dr. Andrew M. Schocket Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Donald McQuarie Dr. Esther Clinton © 2007 Catherine A. Shufelt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor What is a Witch? Traditional mainstream media images of Witches tell us they are evil “devil worshipping baby killers,” green-skinned hags who fly on brooms, or flaky tree huggers who dance naked in the woods. A variety of mainstream media has worked to support these notions as well as develop new ones. Contemporary American popular culture shows us images of Witches on television shows and in films vanquishing demons, traveling back and forth in time and from one reality to another, speaking with dead relatives, and attending private schools, among other things. None of these mainstream images acknowledge the very real beliefs and traditions of modern Witches and Pagans, or speak to the depth and variety of social, cultural, political, and environmental work being undertaken by Pagan and Wiccan groups and individuals around the world. Utilizing social construction theory, this study examines the “historical process” of the construction of stereotypes surrounding Witches in mainstream American society as well as how groups and individuals who call themselves Pagan and/or Wiccan have utilized the only media technology available to them, the internet, to resist and re- construct these images in order to present more positive images of themselves as well as build community between and among Pagans and nonPagans. -

AGRICULTURAL. SYSTEMS of PAPUA NEW GUINEA Ing Paper No. 14

AUSTRALIAN AtGENCY for INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGRICULTURAL. SYSTEMS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ing Paper No. 14 EAST NIEW BRITAIN PROVINCE TEXT SUMMARIES, MAPS, CODE LISTS AND VILLAGE IDENTIFICATION R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, R.L. Hide, D. Fritsch, T. Geob, R. Grau, 5. Heai, P. Hobsb21wn, G. Ling, S. Lyon and M. Poienou REVISED and REPRINTED 2002 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY PAPUA NEW GUINEA DEPARTMENT OF AGRI LTURE AND LIVESTOCK UNIVERSITY OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Papers I. Bourke, R.M., B.J. Allen, P. Hobsbawn and J. Conway (1998) Papua New Guinea: Text Summaries (two volumes). 2. Allen, BJ., R.L. Hide. R.M. Bourke, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, E. Lowes, T. Nen, E. Nirsie, J. Risimeri and M. Woruba (2002) East Sepik. Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. 3. Bourke, R.M., BJ. Allen, R.L. Hide, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, E. Lowes, T. Nen, E. Nirsie, J. Risimeri and M. Woruba (2002) West Sepik Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. 4. Allen, BJ., R.L. Hide, R.M. Bourke, W. Akus, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, G. Ling and E. Lowes (2002) Western Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. 5. Hide, R.L., R.M. Bourke, BJ. Allen, N. Fereday, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, E. Lowes and M. Woruba (2002) Gulf Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. 6. Hide, R.L., R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, T. Betitis, D. Fritsch, R. Grau. L. Kurika, E. Lowes, D.K. Mitchell, S.S. -

Magic, Witchcraft, and Faërie: Evolution of Magical Ideas in Ursula K

Volume 39 Number 2 Article 2 4-23-2021 Magic, Witchcraft, and Faërie: Evolution of Magical Ideas in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea Cycle Oleksandra Filonenko Petro Mohyla Black Sea National University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Recommended Citation Filonenko, Oleksandra (2021) "Magic, Witchcraft, and Faërie: Evolution of Magical Ideas in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea Cycle," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 39 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol39/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract In my article, I discuss a peculiar connection between the persisting ideas about magic in the Western world and Ursula Le Guin's magical world in the Earthsea universe and its evolution over the decades. -

D:\Myfiles\JRS\Issue16

Journal of Ritual Studies 16 (2) 2002 Review Forum This Book Review Forum appeared in the Journal of Ritual Studies 16.2 (2002): pages 4-59. Book Review Forum [page 4] We are pleased to present the following Review Forum of Harvey Whitehouse’s book, Arguments and Icons: Divergent Modes of Religiosity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. 204 pages. ISBN 0-19- 823414-7 (cloth); 0-19-823415-5 (paper). We have given the contributors and the book’s author sufficient space to discuss its themes carefully and thus make a significant contribution to the further analysis of religion and ritual generally. Pamela J. Stewart and Andrew Strathern, Co-editors Journal of Ritual Studies Reviews of this book by: Brian Malley, Pascal Boyer, Fredrik Barth, Michael Houseman, Robert N. McCauley, Luther H. Martin, Tom Sjoblom, and Garry W. Trompf Reply by Harvey Whitehouse Arguments and Icons: Divergent Modes of Religiosity (Harvey Whitehouse, Oxford Univ. Press, 2000) Reviewed by Brian Malley (Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan) [pages 5-7] A friend of mine, a dedicated post-everything-ist, once wistfully remarked that she had an affinity for those old-style “big theories” of religion characteristic of late nineteenth century social thought. I knew what she meant: those “big theories” strove to account both for the form and the very existence of religious belief and practice in terms of a grand scheme of human history. A century of ethnographic and historical investigation has given us a much richer understanding of both large- and small-scale religions, and, to the degree that Mueller, Durkheim, and the like produced empirically tractable theories, they have been disconfirmed. -

Comments on Sorcery in Papua New Guinea

GIALens. (2010):3. <http://www.gial.edu/GIALens/issues.htm> Comments on Sorcery in Papua New Guinea KARL J. FRANKLIN, PH. D. Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics and SIL International ABSTRACT Variations of sorcery and witchcraft are commonly reported in Papua New Guinea. The Melanesian Institute (in Goroka, PNG) has published two volumes (Zocca, ed. 2009; Bartle 2005) that deal extensively with some of the issues and problems that have resulted from the practices. In this article I review Zocca, in particular, but add observations of my own and those of other authors. I provide a summary of the overall folk views of sorcery and witchcraft and the government and churches suggestions on how to deal with the traditional customs. Introduction Franco Zocca, a Divine Word Missionary and ordained Catholic priest from Italy with a doctorate in sociology, has edited a monograph on sorcery in Papua New Guinea (Zocca, ed. 2009). Before residing in PNG and becoming one of the directors of the Melanesian Institute, Zocca worked on Flores Island in Indonesia. His present monograph is valuable because it calls our attention to the widespread use and knowledge of sorcery and witchcraft in PNG. Zocca’s monograph reports on 7 areas: the Simbu Province, the East Sepik Province, Kote in the Morobe Province, Central Mekeo and Roro, both in the Central Province, Goodenough Island in the Milne Bay Province and the Gazelle Peninsula in the East New Britain Province. The monograph follows Bartle’s volume (2005), also published by the Melanesian Institute. Before looking at Zocca’s volume and adding some observations from the Southern Highlands, I include some general comments on the word sanguma . -

Prophet -- a Symbol of Protest a Study of the Leaders of Cargo Cults in Papua New Guinea

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1972 Prophet -- a Symbol of Protest a Study of the Leaders of Cargo Cults in Papua New Guinea Paul Finnane Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Finnane, Paul, "Prophet -- a Symbol of Protest a Study of the Leaders of Cargo Cults in Papua New Guinea" (1972). Master's Theses. 2615. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/2615 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1972 Paul Finnane THE PROPHET--A SYifJ30L OF PROTEST A Study of the Leaders of Cargo Cults · in Papua New Guinea by Paul Finnane OFM A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University, Chicago, in Partial Fulfillment of the-Requirements for the Degree of r.;aster of Arts June 1972 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .• I wish to thank Sister I·llark Orgon OSF, Philippines, at whose urging thip study was undertaken: Rev, Francis x. Grollig SJ, Chair~an of the Department of Anthropology at Loyola University, Chicago, and the other members of the Faculty, especially Vargaret Hardin Friedrich, my thesis • ""' ..... d .. ·+· . super\!'isor.. '\¥ •• ose sugges --ion=? an pcrnpicaciouo cr~.. w1c1sm helped me through several difficult parts o~ the. -

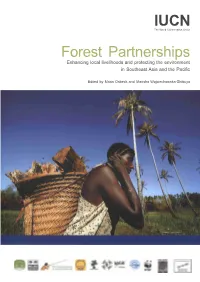

Forest Partnerships Enhancing Local Livelihoods and Protecting the Environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific

IUCN The World Conservation Union Forest Partnerships Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Edited by Maria Osbeck and Marisha Wojciechowska-Shibuya IUCN The World Conservation Union The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: The World Conservation Union (IUCN), Asia Regional Office Copyright: © 2007 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Osbeck, M., Wojciechowska-Shibuya, M. (Eds) (2007). Forest Partnerships. Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. IUCN, Bangkok, Thailand. 48pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1011-2 Cover design by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Cover photos: Local people, Papua New Guinea. A woman transports a basketful of baked sago from a pit oven back to Rhoku village. Sago is a common subsistence crop in Papua New Guinea. Western Province, Papua New Guinea. December 2004 CREDIT: © Brent Stirton / Getty Images / WWF-UK Layout by: Michael Dougherty Produced by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Printed by: Clung Wicha Press Co., Ltd. -

Religion and the Return of Magic: Wicca As Esoteric Spirituality

RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC: WICCA AS ESOTERIC SPIRITUALITY A thesis submitted for the degree of PhD March 2000 Joanne Elizabeth Pearson, B.A. (Hons.) ProQuest Number: 11003543 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003543 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION The thesis presented is entirely my own work, and has not been previously presented for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. The views expressed here are those of the author and not of Lancaster University. Joanne Elizabeth Pearson. RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC: WICCA AS ESOTERIC SPIRITUALITY CONTENTS DIAGRAMS AND ILLUSTRATIONS viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix ABSTRACT xi INTRODUCTION: RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC 1 CATEGORISING WICCA 1 The Sociology of the Occult 3 The New Age Movement 5 New Religious Movements and ‘Revived’ Religion 6 Nature Religion 8 MAGIC AND RELIGION 9 A Brief Outline of the Debate 9 Religion and the Decline o f Magic? 12 ESOTERICISM 16 Academic Understandings of -

The Punishment of Clerical Necromancers During the Period 1100-1500 CE

Christendom v. Clericus: The Punishment of Clerical Necromancers During the Period 1100-1500 CE A Thesis Presented to the Academic Faculty by Kayla Marie McManus-Viana In Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Requirements for the Bachelor of Science in History, Technology, and Society with the Research Option Georgia Institute of Technology December 2020 1 Table of Contents Section 1: Abstract Section 2: Introduction Section 3: Literature Review Section 4: Historical Background Magic in the Middle Ages What is Necromancy? Clerics as Sorcerers The Catholic Church in the Middle Ages The Law and Magic Section 5: Case Studies Prologue: Magic and Rhetoric The Cases Section 6: Conclusion Section 7: Bibliography 3 Abstract “The power of Christ compels you!” is probably the most infamous line from the 1973 film The Exorcist. The movie, as the title suggests, follows the journey of a priest as he attempts to excise a demon from within the body of a young girl. These types of sensational pop culture depictions are what inform the majority of people’s conceptions of demons and demonic magic nowadays. Historically, however, human conceptions of demons and magic were more nuanced than those depicted in The Exorcist and similar works. Demons were not only beings to be feared but sources of power to be exploited. Necromancy, a form of demonic magic, was one avenue in which individuals could attempt to gain control over a demon. During the period this thesis explores, 1100-1500 CE, only highly educated men, like clerics, could complete the complicated rituals associated with necromancy. Thus, this study examines the rise of the learned art of clerical necromancy in conjunction with the re-emergence of higher learning in western Europe that developed during the period from 1100-1500 CE. -

PONERA Abeillei André, 1881; See Under HYPOPONERA. Abyssinica Guérin-Méneville, 1849; See Under MEGAPONERA

BARRY BOLTON’S ANT CATALOGUE, 2020 PONERA abeillei André, 1881; see under HYPOPONERA. abyssinica Guérin-Méneville, 1849; see under MEGAPONERA. abyssinica Santschi, 1938; see under HYPOPONERA. acuticostata Forel, 1900; see under PSEUDONEOPONERA. aemula Santschi, 1911; see under HYPOPONERA. aenigmatica Arnold, 1949; see under EUPONERA. aethiopica Smith, F. 1858; see under STREBLOGNATHUS. aethiopica Forel, 1907; see under HYPOPONERA. *affinis Heer, 1849; see under LIOMETOPUM. affinis. Ponera affinis Jerdon, 1851: 118 (w.) INDIA (Karnataka/Kerala; “Malabar”). Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated). Type-locality: India: Malabar (T.C. Jerdon). Type-depository: unknown (no material known to exist). [Duplicated in Jerdon, 1854b: 102.] [Unresolved junior primary homonym of *Ponera affinis Heer, 1849: 147 (Bolton, 1995b: 360).] Status as species: Smith, F. 1858b: 84; Mayr, 1863: 447; Smith, F. 1871a: 320; Dalla Torre, 1893: 37; Emery, 1911d: 116; Chapman & Capco, 1951: 68; Tiwari, 1999: 29. Unidentifiable to genus; incertae sedis in Ponerinae: Emery, 1911d: 116. Unidentifiable to genus; incertae sedis in Ponera: Bolton, 1995b: 360. Distribution: India. agilis Borgmeier, 1934; see under HYPOPONERA. aitkenii Forel, 1900; see under HYPOPONERA. albopubescens Menozzi, 1939; see under HYPOPONERA. aliena Smith, F. 1858; see under HYPOPONERA. alisana. Ponera alisana Terayama, 1986: 591, figs. 1-5 (w.q.) TAIWAN. Type-material: holotype worker, 5 paratype workers, 4 paratype queens. Type-locality: holotype Taiwan: Chiayi Hsien, Fenchihu (1400 m.), 3.viii.1980 (M. Terayama); paratypes with same data. Type-depositories: NSMT (holotype); NIAS, NSMT, TARI (paratypes). Leong, Guénard, et al. 2019: 27 (m.). Status as species: Bolton, 1995b: 360; Xu, 2001a: 53 (in key); Xu, 2001c: 218 (in key); Lin & Wu, 2003: 68; Terayama, 2009: 109; Yoshimura, et al. -

On Death and Magic: Law, Necromancy and the Great Beyond Eric J

Western New England University School of Law Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2010 On Death and Magic: Law, Necromancy and the Great Beyond Eric J. Gouvin Western New England University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/facschol Part of the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation On Death and Magic: Law, Necromancy, and the Great Beyond, in Law and Magic: A Collection of Essays (Christine A. Corcos, ed., Carolina Academic Press 2010) This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 14 On Death and Magic: Law, Necromancy, and the Great Beyond Eric J. Gouvin* Throughout history humans have been fascinated by the ultimate mystery of life and death. Beliefs about what lies beyond the grave are at the core of many religious prac tices and some magical practices as well. Magicians have long been involved with spirits, ghosts, and the dead, sometimes as trusted intermediaries between the world of the liv ing and the spirit realm and sometimes as mere entertainers.' The branch of magic that seeks communion with the dead is known as necromancy.2 This essay examines instances where the legal system encounters necromancy itself and other necromantic situations (i.e., interactions involving ghosts, the dead, or the spirit world). -

Spiritual Leadership, Salvation, and Disillusionment in Randolph Stow's

Tourmaline and Trauma: Spiritual Leadership, Salvation, and Disillusionment in Randolph Stow’s Novel Cressida Rigney Introduction Australian Literature is, at least internationally, understudied, and far more so than Australian visual arts. A unique, dedicated academic programme within the English department has existed at the University of Sydney since 1962; nevertheless Australian Literature still feels the effect of the cultural cringe associated with colonial countries.1 Despite this, certain authors and texts inspire a relatively steady stream of scholarship. Randolph Stow is one of these. Stow’s compelling, complex, often metaphysical style allows him to use literature to explore religious and spiritual life and its intersections with community. Stow’s Tourmaline (1963) is part of the mid twentieth century post-apocalyptic movement most notably represented by Neville Shute’s 1957 novel On the Beach.2 In Tourmaline Randolph Stow mitigates the fraught relationship between perception and experiences, specifically those relating to the interplay of human responses to spirituality, social structure and character, essential forces in community construction. Stow’s vibrant prose, layered plot, philosophical thematics, and a set of characters painfully human in their lack of holistic appeal absorb his reader. Tourmaline is concerned with a potential conflict between the active and inactive experiential religion dealing with the Cressida Rigney is an Honours student within the University of Sydney in the department of Studies in Religion and an Honours Research Fellow of the Faculty of Arts in collaboration with the Sydney Environment Institute. 1 The University of Sydney, ‘Australian Literature Program: About Us’, at http://sydney.edu.au/arts/australian_literature/about/index.shtml.