Anthropology, Missiological Anthropology. the Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Cultural Anthropology and British Social Anthropology

Anthropology News • January 2006 IN FOCUS ANTHROPOLOGY ON A GLOBAL SCALE In light of the AAA's objective to develop its international relations and collaborations, AN invited international anthropologists to engage with questions about the practice of anthropology today, particularly issues of anthropology and its relationships to globaliza- IN FOCUS tion and postcolonialism, and what this might mean for the future of anthropology and future collaborations between anthropologists and others around the world. Please send your responses in 400 words or less to Stacy Lathrop at [email protected]. One former US colleague pointed out American Cultural Anthropology that Boas’s four-field approach is today presented at the undergradu- ate level in some departments in the and British Social Anthropology US as the feature that distinguishes Connections and Four-Field Approach that the all-embracing nature of the social anthropology from sociology, Most of our colleagues’ comments AAA, as opposed to the separate cre- highlighting the fact that, as a Differences German colleague noted, British began by highlighting the strength ation of the Royal Anthropological anthropologists seem more secure of the “four-field” approach in the Institute (in 1907) and the Associa- ROBERT LAYTON AND ADAM R KAUL about an affinity with sociology. US. One argued that this approach is tion of Social Anthropologists (in U DURHAM Clearly British anthropology traces in fact on the decline following the 1946) in Britain, contributes to a its lineage to the sociological found- deeper impact that postmodernism higher national profile of anthropol- ing fathers—Durkheim, Weber and consistent self-critique has had in the US relative to the UK. -

Cultural Diversity: Cultural Anthropology and Linguistics

1 Cultural Diversity: Cultural Anthropology and Linguistics ANTH 104 Dr. Maria Masucci Summer 2013 Office: Faulkner House 4 Dates: May 21 – June 13 Office phone: 3496 Times: 9:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m.; T, W, TH E-Mail: [email protected] Course Description The discipline of Anthropology challenges us through a comparative approach to become aware of our own cultural preconceptions and to appreciate the tremendous variety of human experiences. In this course we will learn how other perspectives of the world can challenge our assumptions about our own way of life. As an introduction to the field of cultural anthropology students will become acquainted with concepts and methodologies utilized by cultural anthropologists as well as the social and ethical dilemmas that we face conducting cross-cultural research. Learning Goals To help create global citizens who are open to and comfortable with interacting in a multicultural, multilinqual world by helping you: gain an appreciation of the rich cultural diversity of human societies; learn to think critically about assumptions and representations of culture and society. gain competence in the history and central theoretical and methodological concepts and practices of socio-cultural anthropology and linguistics; 2 Therefore, by the end of this course you should have: an appreciation of Anthropological Perspectives, specifically a holistic and comparative perspective of humans and their cultures across time and space and the relevance of anthropology to everyday life; a developing knowledge base of the major concepts, theoretical orientations, methodological approaches and historical trends in anthropology; exposure to and familiarity with ethnographic methods central to the field of cultural anthropology; a more nuanced understanding of how people give meaning to their lives in a rapidly globalizing world and; preparation for intermediate level cultural anthropology courses. -

Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: an Introduction to Harris Brian D

The Behavior Analyst 2007, 30, 37–47 No. 1 (Spring) Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: An Introduction to Harris Brian D. Kangas University of Florida The year 2007 marks the 80th anniversary of the birth of Marvin Harris (1927–2001). Although relations between Harris’ cultural materialism and Skinner’s radical behaviorism have been promulgated by several in the behavior-analytic community (e.g., Glenn, 1988; Malagodi & Jackson, 1989; Vargas, 1985), Harris himself never published an exclusive and comprehensive work on the relations between the two epistemologies. However, on May 23rd, 1986, he gave an invited address on this topic at the 12th annual conference of the Association for Behavior Analysis in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, entitled Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: Common Problems and Radical Solutions. What follows is the publication of a transcribed audio recording of the invited address that Harris gave to Sigrid Glenn shortly after the conference. The identity of the scribe is unknown, but it has been printed as it was written, with the addendum of embedded references where appropriate. It is offered both as what should prove to be a useful asset for the students of behavior who are interested in the studyofcultural contingencies, practices, and epistemologies, and in commemoration of this 80th anniversary. Key words: cultural materialism, radical behaviorism, behavior analysis Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: Common Problems and Radical Solutions Marvin Harris University of Florida Cultural materialism is a research in rejection of mind as a cause of paradigm which shares many episte- individual human behavior, radical mological and theoretical principles behaviorism is not radically behav- with radical behaviorism. -

Collection of Online Sources for Cultural Anthropology Videos In

Collection of Online Sources for Cultural Anthropology Videos in Anthropology Man and His Culture (14:51) The movie shows, in the imaginative form of a 'REPORT FROM OUTER SPACE,' how the ways of mankind might appear to visitors from another planet. Considers the things most cultures have in common and the ways they change as they pass from one generation to the next. Key words: Culture, Cultural universals, Language, Culture Change Chemically Dependent Agriculture (48:59) The change from smaller, more diverse farms to larger single-crop farms in the US has led to greater reliance on pesticides for pest management. Key words: Agriculture; Culture change, Food, Pesticide, Law The Story of Stuff (21:24) The Story of Stuff is a 20-minute, fast-paced, fact-filled look at the underside of our production and consumption patterns. Key words: Culture of consumption; Consumerism, Environment The Real Truth About Religion (26:43) Although the ancients incorporated many different conceptions of god(s) and of celestial bodies, the sun, the most majestic of all entities was beheld with awe, revered, adored and worshiped as the supreme deity. Key words: Religion, Symbolism, Symbolic Language, System of Beliefs Selected by Diana Gellci, Ph.D Updated 5.3.16 Collection of Online Sources for Cultural Anthropology The Arranged Marriage (Kashmiri) (20:48) Niyanta and Rohin, our lovely Kashmiri couple are an epitome of the popular saying "for everyone there is someone somewhere". Love struck when Rohin from South Africa met the Kashmiri beauty from Pune. They decided to get married. Everyone called it an arranged marriage, an "Arranged Marriage" with a rare amalgamation of Beauty, Emotions and above all Trust. -

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by C. Nadia Seremetakis All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7334-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7334-5 To my students anywhere anytime CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Exploring Cultures Chapter One ................................................................................................. 4 Redefining Culture and Civilization: The Birth of Anthropology Fieldwork versus Comparative Taxonomic Methodology Diffusion or Independent Invention? Acculturation Culture as Process A Four-Field Discipline Social or Cultural Anthropology? Defining Culture Waiting for the Barbarians Part II: Writing the Other Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 30 Science/Literature Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Nature, Objects, and Scope of Cultural Anthropology, Ethnology and Ethnography - Paolo Barbaro

ETHNOLOGY, ETHNOGRAPHY AND CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY - Nature, Objects, And Scope Of Cultural Anthropology, Ethnology And Ethnography - Paolo Barbaro NATURE, OBJECTS, AND SCOPE OF CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY, ETHNOLOGY AND ETHNOGRAPHY Paolo Barbaro Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, France Keywords: Anthropology, Archeology, Culture, Ethnography, Ethnology, Human Beings, Humanity, Language, Society, Sociology. Contents 1. Introduction 2. What is Cultural Anthropology? 3. About the use of the expression ‘Cultural Anthropology’ and other terms 4. The Objects of Investigation and the Scope of Cultural Anthropology Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary This chapter gives a broad view of the discipline of Cultural Anthropology: the study of human beings from the perspective of their cultures and societies, both from a synchronic and a diachronic standpoint. Cultural Anthropology is one of the three (or four) major branches of the broader field of Anthropology, and this chapter discusses its nature, objects and scope also in relation in the wider anthropological context, including an analysis of the concept of Ethnology – a synonym of Anthropology as well as a sub- branch dealing with division of human beings into groups, distribution, relations and characteristics. This chapter also analyzes the sub-branch of Ethnography, i.e. the scientific description of specific cultures, sub-cultures, cultural environments or cultural productions on which anthropological theories, analysis and conceptualizations are based. In this way it ushers the reader into the chapters that follow in this volume for deeper aspects of the subjects. The volume, in fact, is organized in order to sketch a panoramic view of the methods employed in, and of the main subject treated by, Cultural Anthropology. -

Awareness of Self As a Cultural Being

Awareness of Self as a Cultural Being Valerie A. Batts, PhD VISIONS, Inc. Foundations of Infant Mental Health Training Program 2013/2014 Central California Children’s Institute, Fresno State November 2013 Awareness Of Self as a Cultural Being Agenda/ "Map” I) Introduction: Self awareness as a first step in providing better services for families • What is the multicultural process of change? • Overview of guidelines for effective cross cultural dialogue (Video clip I) Activity 1: Applying guidelines • Who am I as a cultural being? Exploring multiple identities, Part I Activity 2: Cultural sharing (using cultural artifacts) 2) How does race/ethnicity continue to impact infant mental health practice in 2013? The role of modern oppression • Video clip II • Identifying 5 kinds of "modern isms" Activity 3: Identifying isms • Video clip III • Identifying 5 "survival behaviors"/internalized oppression Activity 4: Identifying survival or i.o. behaviors • 11:45 - 12:45 Working lunch 3) Understanding my multiple identities, Part II Activity 5: Understanding how power impacts identity 4) Identifying alternative behaviors Activity 6: Identifying options in cross cultural infant mental health interactions 5) Closure: Appreciation, Regrets, Learnings and Re-learnings Multicultural Process of Change (at all levels) Monoculturalism Pluralism Rejection of differences and a .Recognize Acceptance, appreciation, belief in the superiority of the .Understand utilization and celebration of dominant group at the following .Appreciate similarities and differences at levels: .Utilize Differences these levels: • Personal • Personal • Interpersonal • Interpersonal • Institutional/Systemic • Institutional/Systemic • Cultural • Cultural (“Emancipatory Consciousness”) Social/Economic Justice Monoculturalism Pluralism (“Melting Pot”) (“Salad Bowl/Fruit Salad”) Assimilation Diversity Exclusion Inclusion *Designed by: Valerie A. -

Anthropology 1

Anthropology 1 ANTHROPOLOGY [email protected] Hillary DelPrete, Assistant Professor (Graduate Faculty). B.S., Tulane Chair: Christopher DeRosa, Department of History and Anthropology University; M.A., Ph.D., Rutgers University. Professor DelPrete is a biological anthropologist with a specialization in modern evolution. The Anthropology curriculum is designed to provide a liberal arts Teaching and research interests include human evolution, human education that emphasizes the scientific study of humanity. Three areas variation, human behavioral ecology, and anthropometrics. of Anthropology are covered: [email protected] • Cultural Anthropology, the comparative study of human beliefs and Christopher DeRosa, Associate Professor and Chair (Graduate Faculty). behavior with special attention to non-Western societies; B.A., Columbia University; Ph.D., Temple University. Fields include • Archaeology, the study of the human cultural heritage from its military history and American political history. Recent research prehistoric beginnings to the recent past; and concerns the political indoctrination of American soldiers. • Biological Anthropology, the study of racial variation and the physical [email protected] and behavioral evolution of the human species. Adam Heinrich, Assistant Professor (Graduate Faculty). B.S., M.A., The goal of the Anthropology program is to provide students with a broad Ph.D., Rutgers University. Historical and prehistoric archaeology; understanding of humanity that will be relevant to their professions, their -

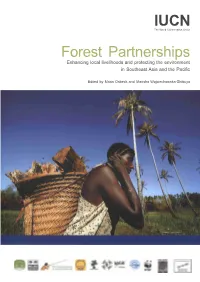

Forest Partnerships Enhancing Local Livelihoods and Protecting the Environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific

IUCN The World Conservation Union Forest Partnerships Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Edited by Maria Osbeck and Marisha Wojciechowska-Shibuya IUCN The World Conservation Union The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: The World Conservation Union (IUCN), Asia Regional Office Copyright: © 2007 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Osbeck, M., Wojciechowska-Shibuya, M. (Eds) (2007). Forest Partnerships. Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. IUCN, Bangkok, Thailand. 48pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1011-2 Cover design by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Cover photos: Local people, Papua New Guinea. A woman transports a basketful of baked sago from a pit oven back to Rhoku village. Sago is a common subsistence crop in Papua New Guinea. Western Province, Papua New Guinea. December 2004 CREDIT: © Brent Stirton / Getty Images / WWF-UK Layout by: Michael Dougherty Produced by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Printed by: Clung Wicha Press Co., Ltd. -

The Role of Acculturation and White Supremacist Ideology

American Psychologist © 2019 American Psychological Association 2019, Vol. 74, No. 1, 143–155 0003-066X/19/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000368 Racial Trauma, Microaggressions, and Becoming Racially Innocuous: The Role of Acculturation and White Supremacist Ideology William Ming Liu and Rossina Zamora Liu Yunkyoung Loh Garrison, Ji Youn Cindy Kim, University of Maryland Laurence Chan, Yu C. S. Ho, and Chi W. Yeung The University of Iowa Acculturation theories often describe how individuals in the United States adopt and incor- porate dominant cultural values, beliefs, and behaviors such as individualism and self- reliance. Theorists tend to perceive dominant cultural values as “accessible to everyone,” even though some dominant cultural values, such as preserving White racial status, are reserved for White people. In this article, the authors posit that White supremacist ideology is suffused within dominant cultural values, connecting the array of cultural values into a coherent whole and bearing with it an explicit status for White people and people of color. Consequently, the authors frame acculturation as a continuing process wherein some people of color learn explicitly via racism, microaggressions, and racial trauma about their racial positionality; White racial space; and how they are supposed to accommodate White people’s needs, status, and emotions. The authors suggest that acculturation may mean that the person of color learns to avoid racial discourse to minimize eliciting White fragility and distress. Moreover, acculturation allows the person of color to live in proximity to White people because the person of color has become unthreatening and racially innocuous. The authors provide recommendations for research and clinical practice focused on understanding the connections between ideology, racism, microaggressions and ways to create psychological healing. -

Multicultural Education As Community Engagement: Policies and Planning in a Transnational Era

Vol. 14, No. 3 International Journal of Multicultural Education 2012 Multicultural Education as Community Engagement: Policies and Planning in a Transnational Era Kathryn A. Davis Prem Phyak Thuy Thi Ngoc Bui University of Hawai`i at Mānoa U. S. A. Through viewing multicultural education as policy and planning that is enacted at national, regional, and local levels in Nepal and Vietnam, we explore the challenges and possibilities of engaging communities. We examine transnationalism, neoliberalism, and globalization as these impact national policies, community ideologies, regional/local economy, social welfare, and education. Critical ethnographic studies further focus on history, place, and culture in engaging communities of policy makers, educators, students, families and activists in reflection and transformation, policy making, and planning. These studies serve to re-envision multicultural education as critical community engagement and transformation within a transnational era. Transnationalism, Neoliberalism, and Education Resisting Monoculturalism in Nepal Reimagining Globalization, Multiculturalism and Education in Vietnam Multicultural Education as Community Engagement Notes References Indigenous and multicultural education across borders reveals ongoing debate over policies affecting achievement among students from linguistically-diverse and socioeconomically-marginal communities (Davis, 2009; Luke, 2008, 2011). Researchers (Evans & Hornberger, 2005; Luke, 2011; Wiley & Wright, 2004) document the negative impact on students of global trends towards one-size-fits-all approaches to basic skills, textbooks, and standardized assessment. These and other scholars from multilingual countries such as Australia, Canada, Namibia, New Zealand, and the Republic of South Africa (Beukes, 2009; Luke, 2011) have argued for policies of inclusion which promote community ideologies and language choice in schools through culturally responsive and linguistically responsible education. -

Flexible Acculturation

FLEXIBLE ACCULTURATION HSIANG-CHIEH LEE National Science and Technology Center for Disaster Reduction, Taiwan “Flexibility” has become an important concept in studies of globalization and transnationalism. Most academic discus- sions fall into the literature of global capitalist restructuring: e.g., Piore and Sabel’s (1984) notion of flexible specialization and David Harvey’s concept (1991) of flexible accumulation. These discussions are centered on economic production and market logics. Theoretical discussions of flexibility about other regimes of power — such as cultural reproduction, the nation- state and family — are relatively insufficient. In this paper, I explore the concept of “flexible acculturation,” first proposed by Jan Nederveen-Pieterse (2007), to show a cultural aspect of transnational flexibility. I situate my discussion in the literature of transmigration studies and define flexible acculturation as having four important virtues: (1) it has diverse social players, rather than just political and economic elites; (2) it refers to interac- tions, not just differences; (3) it involves multiple processes; and (4) it is not just about agency but also about social regulations. These definitions help to explain why flexible acculturation is different from other concepts that have been proposed. I further argue that definitions of important social actors are contingent on a specific set of flexible acculturation processes. Social ac- tors discussed in this paper include governments, the public, transmigrants, and women. “Flexibility” has become an important concept in studies of globalization and transnationalism, especially after David Harvey’s Hsiang-Chieh Lee (PhD, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2008) is a senior assistant research fellow in National Science and Technology Center for Disaster Reduction in Taiwan.