John Baskerville: Shaping the Alphabet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Library of Birmingham Archives & Collections

Library of Birmingham Archives & Collections John Baskerville of Birmingham, printer 1706 John Baskerville born 1737 Kept a school in the Bull Ring where he taught writing and book-keeping, and carved monumental inscriptions at Birmingham 1740 Started business at Moor Street as a japanner 1750 Began to occupy himself with type-founding 1757 After experimenting for several years, he produced a type with which he was satisfied 1758 Produced his Milton Elected printer to Cambridge University for ten years 1760 First printed his edition of the Prayer Book 1763 Printed his edition of the Bible 1770 A Quarto Horace 1772-3 A famous series of quarto editions of Latin authors 1775 John Baskerville died 1779 His printing plant purchased by Beaumarchaise “He had the reputation of being the finest printer of modern times, though the opinion of contemporary experts was somewhat unfavourable to his type.” The Concise Dictionary of National Biography, from earliest times to 1985, Volume I: A-F, Oxford University Press, 1992. “His principal trade was in japanned goods. An immigrant from Worcestershire, starting with very little capital, he began in Birmingham as a stone-cutter, was then a writing master and set up as a manufacturer of japanned goods in Moor Street in 1740. From 1745 his home was a fine house on what was then the fringe of the town, at Easy Hill [i.e. Baskerville House], and from there he directed his factory for japanned ‘tea tables, waiters, and trays’ and his printing business. Among his innovations was the introduction of papier-mâché into this country. -

History of Moveable Type

History of Moveable Type Johannes Gutenberg invented Moveable Type and the Printing Press in Germany in 1440. Moveable Type was first made of wood and replaced by metal. Example of moveable type being set. Fonts were Type set on a printing press. organized in wooden “job cases” by Typeface, Caps and Lower Case, and Point Size. Typography Terms Glyphs – letters (A,a,B,b,C,c) Typeface – The aesthetic design of an alphabet. Helvetica, Didot, Times New Roman Type Family – The range of variations and point size available within one Typeface. Font (Font Face) – The traditional term for the complete set of a typeface as it relates to one point size (Font Face: Helvetica, 10 pt). This would include upper and lower case glyphs, small capitals, bold and italic. After the introduction of the computer, the word Font is now used synonymously with the word Typeface, i.e. “What font are you using? Helvetica!” Weight – the weight of a typeface is determined by the thickness of the character outlines relative to their height (Hairline, Thin, Ultra-light, Extra-light, Light, Book, Regular, Roman, Medium, Demi-bold, Semi-bold, Bold, Extra-bold, Heavy, Black, Extra-black, Ultra-black). Point Size – the size of the typeface (12pt, 14pt, 18pt). Points are the standard until of typographic measurement. 12 points = 1 pica, 6 picas = 72 points = 1 inch. (Example right) A general rule is that body copy should never go below 10pt and captions should never be less than 8pt. Leading – or line spacing is the spacing between lines of type. In metal type composition, actual pieces of lead were inserted between lines of type on the printing press to create line spacing. -

Georgia Vs Bodoni Y Y Y Y

Georgia, a relatively new serif typeface, was designed in 1993 by Matthew Carter. Microsoft adopted this typeface to be the serif companion to Verdana both of which were intended to be optimally read on a digital screen. Georgia was ironically used in the branding for the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, Georgia. Georgia has many similarities with Times New Roman, but its differences make Georgia much more legible in the digital format. Over 200 years ago, Giambattista Bodoni designed a classic serif typeface that has been used prevalently in design ever since. The early versions of Bodoni were considered transitional but have since been altered to be a modern Didone typeface. Giambattista Bodoni looked to the ideas of John Baskerville when designing this font. He also studied the French type founders Pierre Simon Fournier and Firmin Didot and drew inspiration from their work but ultimately found his own style of typography. Although Bodoni is said to be difficult to read in digital format, printers have acceptedk Bodoni as a beautiful and classic typeface. Although Bodoni and Georgia are separated greatly by age, the both have roots in the transitional typeface catagory. Bodoni has developed over time to be a much more modern typeface, while Georgia has stayed truer to its original design. The greatest similarities to be found between Georgia and Bodoni are when they are bold and oblique. The serifs become much more rounded. Bodoni already has proven its longevity, and in a few hundred years, Georgia may prove to as well. Southern Charm Georgia vs Bodoni y y y y. -

Library of Birmingham Supplement

© Christian Richters www.libraryofbirmingham.com Published by History West Midlands www.historywm.com THE NEW LIBRARY OF BIRMINGHAM he £188.8 million Library of Birmingham stands on Centenary Square, at the heart of Birmingham; an area of the city not far from New Street Station which is currently undergoing major refurbishment. It has been built on the site Tof a former car park and is joined with the neighbouring Birmingham Repertory Theatre. Dutch architects Mecanoo designed the building, the award-winning support services and construction company Carillion was the principal contractor, and Capita Symonds was the project manager. © Simon Hadley The new library has ten levels: nine above ground and one lower Brian Gambles, Project Director, Library of Birmingham ground floor. The first to eighth floors of the building are wrapped by an intricate metal façade, reflecting the gasometers, tunnels, canals irmingham has always been a city that and viaducts which fuelled Birmingham’s industrial growth. has valued libraries and the city’s Central Library, built in 1974, was one Highlights of the new building include a studio theatre seating of the biggest in Europe and 300 people, a performance area and children’s spaces, two outdoor garden terraces, an outdoor amphitheatre in Centenary Bwelcomed a huge number of visitors through its doors every day - children and adults reading Square, and a panoramic viewing gallery offering stunning views for pleasure, as well as students and adults from one of the highest points in the city. hungry to learn. A 'Golden Box' of secure archive storage occupies two levels of the The new Library of Birmingham is taking library building, within which the city’s internationally significant collection services to a whole new level, redefining what a of archives, photography and rare books is housed. -

A Brief History of Typefaces the Invention of Printing Movable Type Was Invented by Johannes Gutenberg in Fifteenth-Century Germany

A brief history of typefaces The invention of printing Movable type was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in fifteenth-century Germany. His typography took cues from the dark, dense handwriting of the period, called “blackletter.” The traditional storage of fonts in two cases, one for majuscules and one for minuscules, yielded the terms “uppercase” and “lowercase” still used today. Working in Venice in the late fifteenth century, Nicolas Jenson created letters that combined gothic calligraphic traditions with the new Italian taste for humanist handwriting, which were based on classical models. )ADMIT)HAVEHADALITTLEWORKDONE 2PCFSU4MJNCBDITUZMFE!DOBE+FOTPO BGUFS/JDPMBT+FOTPOTSPNBOUZQFT ANDTHEITALICSOF,UDOVICODEGLI!RRIGHI DSFBUFEJOmGUFFOUIDFOUVSZ*UBMZ )DONTLOOKADAYOVERFIVEHUNDRED DO) )ADMIT)HAVEHADALITTLEWORKDONE 2PCFSU4MJNCBDITUZMFE!DOBE+FOTPO BGUFS/JDPMBT+FOTPOTSPNBOUZQFT ANDTHEITALICSOF,UDOVICODEGLI!RRIGHI DSFBUFEJOmGUFFOUIDFOUVSZ*UBMZ )DONTLOOKADAYOVERFIVEHUNDRED DO) The Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius distributed inexpensive, small-format books in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries to a broad, international public. His books used italic types, a cursive form that economized printing by allowing more words to fit on a page. This page combines italic text with roman capitals. Integrated uppercase and lowercase typefaces. The quick brown fox ran over lazy d the lazy dog 2 or 3 times. ITC Garamond, 1976 The quick brown fox ran over the lazy d lazy dog 2 or 3 (2 or 3) times. Adobe Garamond, 1986 The quick brown fox ran over the lazy d lazy dog 2 or 3 (2 or 3) times. Garamond Premier Regular, 2005 Garamond typefaces, based on the Renaissance designs of Claude Garamond, sixteenth century Enlightenment and abstraction The painter and designer Geofroy Tory believed that the proportions of the alphabet should reflect the ideal human form. -

Quiz 1 Review 1

Quiz 1 Review 1. Printing was invented in: !A. France !B. China !C. Germany !D. Japan 1. Printing was invented in: !A. France !B. China !C. Germany !D. Japan Printing was invented by the Chinese. The earliest wood block print fragments are dated around 220 A.D. Chops, pictured here, were made by carving calligraphic characters into a flat surface of jade, silver, ivory etc. Around 500 A.D. Chops were made by carving the negative space around the characters so the character would be printed in ink surrounded by the white of the paper. Printing was invented by the Chinese. The earliest wood block print fragments are dated around 220 A.D. Chops, pictured here, were made by carving calligraphic characters into a flat surface of jade, silver, ivory etc. Around 500 A.D. Chops were made by carving the negative space around the characters so the character would be printed in ink surrounded by the white of the paper. 2. The use of movable type in printing was invented by: !A. Bì Sh"ng !B. Johannes Gutenberg !C. John Baskerville !D. Marcus Aurelius 2. The use of movable type in printing was invented by: !A. Bì Sh"ng !B. Johannes Gutenberg !C. John Baskerville !D. Marcus Aurelius The use of movable type in printing was invented in 1041 AD by Bi Sheng in China. Sheng used clay type and adhered it to a board with wax. The use of movable type in printing was invented in 1041 AD by Bi Sheng in China. Sheng used clay type and adhered it to a board with wax. -

TRACING BASKERVILLE John Baskerville (Source: Birmingham Museum); Virgil Aeneid with Expansive Margins and Fine Alignment, 1757 (Source: Typefaces for Books)

MiraCosta College / oceanside MAT 155 Graphic Design 2 : Typography Min Choi // Fall 2017 TRACING BASKERVILLE John Baskerville (Source: Birmingham Museum); Virgil Aeneid with expansive margins and fine alignment, 1757 (Source: Typefaces for Books) “Having been an early admirer of the beauty of letters, I became insensibly desirous of contributing to the perfection of them. I formed to myself ideas of greater accuracy than had yet appeared, and had endeavoured to produce a set of types according to what I conceived to be their true proportion.” — John Baskerville, preface to Milton, 1758 (Anatomy of a Typeface) http://idsgn.org/posts/know-your-type-baskerville/ ABOUT BASKERVILLE Baskerville is known as a Transitional typeface. Transitional refers to fonts that bridge the gap between the organic Old Style typefaces and the mechanical looking structure of the modern fonts. Characteristics of Transitional fonts include: A greater contrast between thick and thin strokes, wider, gracefully bracketed serifs with flat bases, larger x-height, vertical stress in rounded strokes, the height of capitals more closely matching that of ascenders, and the numerals and cap height are consistent.* John Baskerville was an English writing master, stonecutter, letter designer, typefounder and printer. Although in his lifetime he was un- derappreciated compared with his close contemporary William Caslon, he is now recognized as the other half of the duo that transformed English printing and type founding. After first working as an accomplished writing master and headstone engraver in Birmingham, he found business success japanning (coating with black varnish) trays and snuff-boxes. His quest for perfection meant his first complete book took until 1757 to produce, during which time he made major innovations in press construction (making a flatter, sturdier bed), printing ink (blacker, more even, and quicker-drying), papermaking (wove instead of laid), and of course letter design (which Handy cut to Baskerville’s designs). -

Typography Consultant to Monotype Corporation*

Typography TYPOGRAPHY The art of type TYPE All the letters (abc), Numbers (123) & characters (; ? @) of the alphabet. MONOTYPE Trade name for hot metal composition system Monotype Corporation Machine Shop Hot Metal Composition FONT Type or letter style Examples: Impact Baskerville Old Face Agency Cooper Black Broadway VARIATIONS OF TYPE Width of letters: regular, or Weight of letters: light, regular, bold, heavy TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES • SERIF: Letters that have feet or tails. • SAN SERIF: Letters without feet or tails. • SCRIPT: Letters that simulate handwriting (cursive) and/or calligraphy • DECORATIVE: Letters that have character, are unique in style. Examples of TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES Having feet or SERIF tails Having feet or tails More examples of “SERIF” fonts SERIF SERIF SERIF SERIF Examples of TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES Having NO feet SAN SERIF or tails Having NO feet or tails More examples of “SAN SERIF” fonts SAN SERIF SAN SERIF SAN SERIF SAN SERIF SAN SERIF Examples of TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES Rule of thumb:Script When using a Script Resembles handwriting, font, do not write in all capital letters, cursive lettering or calligraphy. it is too hard to read. SCRIPT More examples of “SCRIPT” fonts Script Script Script Examples of TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES Fonts that are unique in style and typically only used for headlines, or one word emphasis. More examples of “DECORATIVE” fonts DECORATIVE DECORATIVE DECORATIVE DECORATIVE POINT Type is measured in points Smallest typographical unit. 1 point = 1/72 of an inch 36 point = ½ of an inch 72 point = 1 inch SPACING TRACKING: T R A C K I N G Adjusting space between all letters equally. -

Type Classifications

Type Classifications Individual characteristics of a typeface’s drawing are what distinguishes fonts. Most characteristics are related to historical differences. Classifying type helps designers grasp the differences in styles and to select a appropriate for a project. The historical development of type is tied to the evolution of the technology used to make it and print it. Up to the 15th century, type was drawn by hand or a brush, reed pen or chisel These methods influenced the aesthetics of type. In the mid- 1500’s casting letter in lead allowed for a new precision of form. As technology has changed type has become more finely drawn and flexible. The classification system was devised in the 19th century, when printer sought to identify a heritage analogous to art history. Humanist — Calligraphy and movement of the hand Transitional and Modern — abstract and less organic Humanist/Transitional/Modern correspond roughly to Renaissance, Baroque and Enlightenment periods of Art and Literature. 20th and 21st century typefaces continue to be based on historic characteristics. Type Classifications Old Style (1500’s-1700’s) Garamond Old Style 1615 Humanistic - Old Style fonts: Jensen, Centaur A Garamond Old Style /1615 Transitional A Baskerville 1757 A Modern A Bodoni 1788 Egyptian or Slab Serif Century Expanded 1894 A Sans Serif A Helvetica 1957 Type Classifications Humanist (1460’s-70’s) Ae strong roots in calligraphy Fonts Jenson, Kennerly, Centaur, Stempel Schneidler, Verona, Lutetia, Jersey, Lynton. Characteristics 1. Sloping cross-bar on the lowercase “e”; 2. Relatively small x-height; 3. Low contrast between “thick” and “thin” strokes (little variation in the stroke width); 4. -

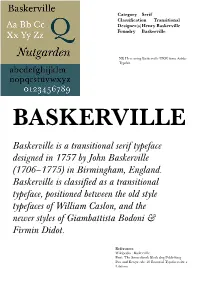

Sans Serif Typefaces By: Years, All of Which Were Designed by Ben- Ton and Issued by A.T.F

Category Serif Classification Transitional Designer(s) Henry Baskerville Foundry Baskerville NB Here using Baskerville URW from Adobe Typekit BASKERVILLE Baskerville is a transitional serif typeface designed in 1757 by John Baskerville (1706–1775) in Birmingham, England. Baskerville is classified as a transitional typeface, positioned between the old style typefaces of William Caslon, and the newer styles of Giambattista Bodoni & Firmin Didot. References Wikipedia : Baskerville Font: The Sourcebook Black dog Publishing Pau and Berger eds: 30 Essential Typefaces for a Lifetime History CHARACTERISTICS In Birmingham, England, Henry Baskerville ad- vanced the use of more delicate typefaces that could The Baskerville typeface is the result of withstand the repeated poundings on the press. He John Baskerville’s intent to improve upon also developed smoother paper so the typefaces could the types of William Caslon. He was aim- print without breaks or clogs. Had an airy quality ing at simplicity and quiet refinement due to the lightness of the letterforms and generosity though: of the page margins. Melted down his type after each printing. • increasing the contrast between thick and thin strokes Baskerville’s typeface was the culmination of a larg- • making the serifs sharper and more er series of experiments to improve legibility which tapered also included paper making and ink manufactur- • shifting the axis of rounded letters to a ing. His background as a writing master is evident more vertical position. in the distinctive swash tail on the uppercase Q and • making curved strokes more circular in in the cursive serifs in the Baskerville Italic. shape and making characters more regu- lar. -

Created Caslon Font: Used for the Declaration of Independence • Influenced Many Contemporary Typographers • Known Style: Old Style, Roman John Baskerville

Typography TYPOGRAPHY The art of type TYPE All the letters (abc), Numbers (123) & characters (; ? @) of the alphabet. MONOTYPE Trade name for hot metal composition system Monotype Corporation Machine Shop Hot Metal Composition FONT Type or letter style VARIATIONS OF TYPE Width of letters: regular, or Weight of letters: light, regular, bold, heavy TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES • SERIF: Letters that have feet or tails. • SAN SERIF: Letters without feet or tails. • SCRIPT: Letters that simulate handwriting (cursive) and/or calligraphy • DECORATIVE: Letters that have character, are unique in style. Examples of TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES Having feet or SERIF tails Having feet or tails More examples of “SERIF” fonts SERIF SERIF SERIF Examples of TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES Having NO feet SAN SERIF or tails Having NO feet or tails More examples of “SAN SERIF” fonts SAN SERIF SAN SERIF SAN SERIF SAN SERIF Examples of TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES Resembles handwriting, Rule of thumb: When using a Script cursive lettering or calligraphy. font, do not write in all capital letters, it is too hard to read. More examples of “SCRIPT” fonts Script Script Examples of TYPESTYLE CATEGORIES Fonts that are unique in style and typically only used for headlines, or one word emphasis. More examples of “DECORATIVE” fonts DECORATIVE DECORATIVE DECORATIVE DECORATIVE POINT Type is measured in points Smallest typographical unit. 1 point = 1/72 of an inch 36 point = ½ of an inch 72 point = 1 inch SPACING TRACKING: Adjusting space between all letters equally. KERNING: Adjusting space between two letters. LEADING: Adjusting space between sentences. BASELINE The line where all letters stand on. Typographical Designers Study all the information in orange of the next few pages Three Famous English Type Designers • William Caslon • John Baskerville • Stanley Morison William Caslon Caslon Font 1. -

Catalog of the Peal Exhibition: the Book Arts John Spalding Gatton University of Kentucky

The Kentucky Review Volume 4 Number 1 This issue is devoted to a catalog of an Article 11 exhibition from the W. Hugh Peal Collection in the University of Kentucky Libraries. 1982 Catalog of the Peal Exhibition: The Book Arts John Spalding Gatton University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Gatton, John Spalding (1982) "Catalog of the Peal Exhibition: The Book Arts," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol4/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1te" The Book Arts l to te >f 112. JAMBLICHUS. De mysteriis Aegyptiorum, Chaldaeorum, Assyriorum. Venice: Aldus, 1497. 1eir Incunabula, Latin for "swaddling clothes," describes books produced in the infancy of printing, especially those printed before 1500. In 1428 Johann Gutenberg began experimenting in Strasbourg ill with cast letters and a press for printing, later developing his k invention with Johann Fust in Mainz about 1445. The first great ps production of this new art was a forty-two-line Bible, completed l about 1455 and generally attributed to Gutenberg. ed The scholar Aldus Manutius (1449-1515) founded an academy in Venice for the study of Greek and Latin.