Dresden--History, Stage, Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Christstollen, Der Stollen Oder Die Stolle

Der Christstollen, der Stollen oder die Stolle (die Schreibweise „Stolln“ ist regional nur für die Bergwerksanlage Stollen gebräuchlich) ist ein bekanntes Weihnachts- und Gebildegebäck. Die Form und das Aussehen des Gebäcks sollen an das gewickelte Christkind erinnern. angeschnittener Christstollen Detailaufnahme Stollen sind Gebäcke aus schwerem Hefeteig. Sie enthalten mindestens 3 kg Butter oder Margarine sowie 6 kg Trockenfrüchte – ausschließlich Rosinen, Sultaninen oder Korinthen – sowie Zitronat und Orangeat, bezogen auf 10 kg Mehl. Geschichte Der handwerkliche Christstollen ist das Weihnachtsgebäck mit der wohl längsten Tradition in Deutschland. Die erste urkundliche Erwähnung erfolgte „anno 1329“ in Naumburg (Saale), als Weihnachtsgabe für den Bischof Heinrich. Damals waren Stollen sehr magere Backwerke aus Hefeteig für das christliche Adventsfasten. Die bis heute unveränderte Form stellt ein Gebildebrot dar, welches an das in Windeln liegende Jesuskind erinnern soll. Dies erklärt auch die weiße Zuckerschicht außen. Die traditionelle Form ist bis heute unverändert. Katholische Dogmen erlaubten in der Fastenzeit seinerzeit weder Butter noch Milch. Stollenteige durften nur aus Wasser, Hafer und Rüböl geknetet werden. Papst Innozenz VIII. schickte 1491 ein als „Butterbrief“ bekanntes Schreiben, das Butter statt Öl erlaubte. Der „Butterbrief“ war an die Bedingung geknüpft, Buße zu zahlen, die unter anderem zum Bau des Freiberger Doms verwendet wurde. Der Butterbrief galt nur für das Herrscherhaus und dessen Lieferanten, wurde wohl aber bald großzügig ausgelegt. Man kann also mit Recht sagen, dass ein Papst am heutigen Stollenrezept mitgewirkt hat. Nach der Überlieferung war es die Idee des Hofbäckers Heinrich Drasdo in Torgau (Sachsen), den vorweihnachtlichen Fastenstollen zum Weihnachtsfest mit reichhaltigen Zutaten wie zum Beispiel Früchten zu ergänzen. -

Dresden Makes Winter Sparkle

Tourism Dresden makes winter sparkle www.dresden.de/events Visit Dresden e City of Christmas A Dresden welcome If you like Christmas, you’ll love Dresden. A grand total of twelve completely different Christmas markets, from the by no means Dark Ages to the après- ski charm of Alpine huts, makes for wonderfully conflicting decisions. Holiday sounds fill the air throughout the city. From the many oratorios to Advent, organ and gospel concerts, Dresden’s churches brim with FIVE STARS IN festive insider tips. Christmas tales also come to life in the city’s theatres whilst museums PREMIUM LOCATION host special exhibitions and boats bejewelled with lights glide along the Elbe. If only Christmas could last more than just a few weeks … Dresden Christmas markets ................................................................. 4 INFORMATION & OPENING OFFER T 036461-92000 I [email protected] Dresden winter magic ........................................................................... 8 www.elbresidenz-bad-schandau.net Concerts, Theatre, Shows..................................................................... 10 Boat Trips, Tours ................................................................................... 16 Exhibitions ............................................................................................ 18 Christmas through the Region ........................................................... 20 Shopping at the Advent season .......................................................... 23 Package offer: Advent in -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

Dresden.De/Events Visit Dresden Christmas Magic in the Dresden Elbland Region

Winter Highlights 2018/2019 www.dresden.de/events Visit Dresden Christmas magic in the Dresden Elbland region Anyone who likes Christmas will love Dresden. Eleven very distinct Christmas markets make the metropolis on the Elbe a veritable Christmas city. Christmas in Dresden – that also means festive church concerts, fairy tale readings and special exhibitions. Or how about a night lights cruise on the Elbe? Just as the river itself connects historic city-centre areas with gorgeous landscapes, so the Christmas period combines the many different activities across the entire Dresden Elbland region into one spellbinding attraction. 584th Dresden Striezelmarkt ..................................................... 2 Christmas cheer everywhere Christmas markets in Dresden .................................................. 4 Christmas markets in the Elbland region ................................... 6 Events November 2018 – February 2019 ............................................... 8 Unique experiences ................................................................... 22 Exhibitions ................................................................................. 24 Advent shopping ....................................................................... 26 Prize draw .................................................................................. 27 Packages .................................................................................... 28 Dresden Elbland tourist information centre Our service for you ................................................................... -

Classic Germany

CLASSIC GERMANY September 25-October 9, 2017 15 days for $5,592 total price from Boston, New York, Philadelphia ($4,895 air & land inclusive plus $697 airline taxes and fees) This tour is provided by Odysseys Unlimited, six-time honoree Travel & Leisure’s World’s Best Tour Operators award. An Exclusive Small Group Tour for Alumni & Friends of Duke University Dear Duke Alumni and Friends, We invite you to join us on an exclusive 15-day journey through Germany. Our small group will experience the best this country has to offer, from its famed Black Forest to its classic cities – Heidelberg, Munich, and Berlin. Guests on this tour will have the opportunity to be in Munich during the Oktoberfest celebrations to enjoy the sights, sounds, smells, and tastes of traditional Bavaria. Our tour begins in Frankfurt with a relaxing cruise through the Rhine River Valley. We discover the quintessential German city of Heidelberg then travel to the storied Black Forest. Next, experience the breathtaking Bavarian Alps, fairy tale Neuschwanstein Castle, and the Bavarian capital of Munich. After visiting the memorial at Dachau and the historic city of Nuremberg, travel on to Dresden to tour the beloved Semper Opera House and Dresden Castle’s Green Vault. Continue on to Meissen and Germany’s cultural heart, Berlin, where we visit the Brandenburg Gate, the Pergamon Museum, and the Berlin Wall Memorial. Space on this exclusive Duke departure is limited to 24 guests in total and will fill quickly. As the group grows in size, we will make every attempt to find a Duke host who will join the program to add a uniquely Duke perspective to the experience. -

A Boutique Stay That Avoids an Iron Curtain Vibe Changing the Oil, Filling up Petrol and Examining the Spare Tyre

12 Friday, August 1, 2014 www.thenational.ae The National weekend travel my kind of place Dresden, Germany travelling with kids Solving being Phoenix from the fire driven to distraction The once-devastated city has been restored to its glorious best, with many modern attractions, writes David Whitley Why Dresden? driving holiday in New Zealand There’s an overwhelming sense of taught us that be- a city trying to grasp back what it ing cooped up in once had. The day that everything Aa car for hours at a stretch changed was February 13, 1945, isn’t all that bad. when Allied bombers unleashed Within the first hour a firebombing campaign of of picking up our rental unprecedented savagery. Dresden, car in Auckland, both long regarded as the most beautiful my daughters vomited. city in Germany, was obliterated. We’re at the beginning That which was lost was largely of a 10-day holiday. The built in the late 17th century and plan is to drive to Christ- early 18th under Augustus the church and then Queens- Strong, the autocratic ruler of town, before looping back Saxony who had an enormous up to Auckland. Except that appetite for all things blingy and the car is now smelling to self-aggrandising. The Altstadt high heaven. (Old Town) became a Baroque We stop off at a grocery masterpiece. Over the decades store and buy cleaning sup- since the end of the Second World plies, wondering if we’re do- War, the pieces of the jigsaw have ing the right thing by driv- been painstakingly put back ing so many miles with two together. -

SCHLOESSERLAND SACHSEN. Fireplace Restaurant with Gourmet Kitchen 01326 Dresden OLD SPLENDOR in NEW GLORY

Savor with all your senses Our family-led four star hotel offers culinary richness and attractive arrangements for your discovery tour along Sa- xony’s Wine Route. Only a few minutes walking distance away from the hotel you can find the vineyard of Saxon master vintner Klaus Zimmerling – his expertise and our GLORY. NEW IN SPLENDOR OLD SACHSEN. SCHLOESSERLAND cuisine merge in one of Saxony’s most beautiful castle Dresden-Pillnitz Castle Hotel complexes into a unique experience. Schloss Hotel Dresden-Pillnitz August-Böckstiegel-Straße 10 SCHLOESSERLAND SACHSEN. Fireplace restaurant with gourmet kitchen 01326 Dresden OLD SPLENDOR IN NEW GLORY. Bistro with regional specialties Phone +49(0)351 2614-0 Hotel-owned confectioner’s shop [email protected] Bus service – Elbe River Steamboat jetty www.schlosshotel-pillnitz.de Old Splendor in New Glory. Herzberg Żary Saxony-Anhalt Finsterwalde Hartenfels Castle Spremberg Fascination Semperoper Delitzsch Torgau Brandenburg Senftenberg Baroque Castle Delitzsch 87 2 Halle 184 Elsterwerda A 9 115 CHRISTIAN THIELEMANN (Saale) 182 156 96 Poland 6 PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR OF STAATSKAPELLE DRESDEN 107 Saxony 97 101 A13 6 Riesa 87 Leipzig 2 A38 A14 Moritzburg Castle, Moritzburg Little Buch A 4 Pheasant Castle Rammenau Görlitz A72 Monastery Meissen Baroque Castle Bautzen Ortenburg Colditz Albrechtsburg Castle Castle Castle Mildenstein Radebeul 6 6 Castle Meissen Radeberg 98 Naumburg 101 175 Döbeln Wackerbarth Dresden Castle (Saale) 95 178 Altzella Monastery Park A 4 Stolpen Gnandstein Nossen Castle -

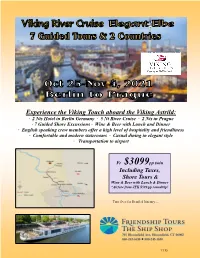

Oct 25 '21 Elbe.Pub

Experience the Viking Touch aboard the Viking Astrild: · 2 Nts Hotel in Berlin Germany · 5 Nt River Cruise · 2 Nts in Prague · 7 Guided Shore Excursions · Wine & Beer with Lunch and Dinner · English speaking crew members offer a high level of hospitality and friendliness · Comfortable and modern staterooms · Casual dining in elegant style · Transportation to airport Fr $3099pp twin Including Taxes, Shore Tours & Wine & Beer with Lunch & Dinner *Airfare from JFK $599.pp roundtrip! Turn Over for Detailed Itinerary…. T115 Day 1: Fly to Berlin, Germany. Deluxe motorcoach to JFK airport to catch our flights to Berlin, Germany. Day 2: Arrive Berlin. Meet your Viking Representative at the airport and transfer to your hotel. Welcome to Germany! After check-in, you have free time to get acquainted with the city, or join Viking’s Welcome Walk to stretch your legs. Day 3: Berlin, Germany. After breakfast, enjoy a panoramic tour of the vibrant German capital, which has seen its fair share of dramatic changes in the last century. See the Reichstag with its spectacular glass dome, the historic Brandenburg Gate, Checkpoint Charlie and many other iconic sites. Enjoy the remainder of your day at leisure. Day 4: Berlin / Wittenberg. After breakfast, travel to Potsdam. Tour Sanssouci Palace, a perfect example of German ro- coco architecture, built by Prussian king Frederick the Great in the 18th century. Built as a summer retreat, it became his personal sanctuary and place to relax in the company of his beloved dogs. Wander through the rooms of the elegant palace and stroll through the magnificent gardens. -

River Cruises Aboard Europe’S Only All-Suite, All-Balcony River Ships True Luxury All-Suite | All-Balcony | All-Butler Service | All-Inclusive

���� ALL-INCLUSIVE RIVER CRUISES ABOARD EUROPE’S ONLY ALL-SUITE, ALL-BALCONY RIVER SHIPS TRUE LUXURY ALL-SUITE | ALL-BALCONY | ALL-BUTLER SERVICE | ALL-INCLUSIVE Travelling Europe’s great waterways with Crystal is truly an exercise in superlatives. Nowhere else will you encounter state-of-the-art ships as spacious, service ratios as high, cuisine as inspired, and cultural immersion as enriching. These defining hallmarks of the Crystal Experience have helped us become the World’s Most Luxurious River Cruise Line — and a rising tide of accolades from travel publications, cruise critics and past guests confirms that these are indeed journeys far beyond compare. The All-Inclusive CRYSTAL EXPERIENCE® INCLUDES BOOK NOW SAVINGS OPEN BARS & LOUNGES with complimentary fine wines, champagnes, spirits & speciality coffees MICHELIN-INSPIRED CUISINE in up to three dining venues plus 24-hour in-suite dining COMPLIMENTARY SHORE EXCURSIONS IN EVERY PORT CRYSTAL SIGNATURE EVENT on select itineraries NIGHTLY ENTERTAINMENT COMPLIMENTARY, UNLIMITED WI-FI PRE-PAID GRATUITIES CALL CRYSTAL ON 020 7399 7604 OR CONTACT YOUR PREFERRED TRAVEL ADVISOR THE ALL-INCLUSIVE WORLD OF CRYSTAL RIVER CRUISES 8 Your Delight is our Pleasure 10 Your Personal Sanctuary 12 Devoted to Your Comfort 14 Inspiration On Board & On Land 16 A World of Culinary Delights 26 Signature Hallmarks 38 Value Comparison 40 Fleet Overview 42 Uniquely River DESTINATIONS 46 Danube River 50 Delightful Danube 52 Magnificent Danube 54 Danube Serenade 56 Treasures of the Danube 58 Pre- and Post-Cruise -

The Family Bach November 2016

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra Jane Glover, Music Director Violin 1 Flute Gina DiBello, Mary Stolper, principal concertmaster Alyce Johnson Kevin Case, assistant Oboe concertmaster Jennet Ingle, principal Kathleen Brauer, Peggy Michel assistant concertmaster Bassoon Teresa Fream William Buchman, Michael Shelton principal Paul Vanderwerf Horn Violin 2 Samuel Hamzem, Sharon Polifrone, principal principal Fritz Foss Ann Palen Rika Seko Harpsichord Paul Zafer Stephen Alltop François Henkins Viola Elizabeth Hagen, principal Terri Van Valkinburgh Claudia Lasareff- Mironoff Benton Wedge Cello Barbara Haffner, principal Judy Stone Mark Brandfonbrener Bass Collins Trier, principal Andrew Anderson Performing parts based on the critical edition Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: The Complete Works (www.cpebach.org) were made available by the publisher, the Packard Humanities Institute of Los Altos, California. The Family Bach Jane Glover, conductor Sunday, November 20, 2016, 7:30 PM North Shore Center for the Performing Arts, Skokie Tuesday, November 22, 2016, 7:30 PM Harris Theater for Music and Dance, Chicago Gina DiBello, violin Mary Stolper, flute Sinfonia from Cantata No. 42 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Adagio and Fugue for 2 Flutes Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and Strings in D Minor (1710-1784) Adagio Allegro Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major J. S. Bach Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Gina DiBello, violin INTERMISSION Flute Concerto in B-flat Major Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788) Allegretto Adagio Allegro assai Mary Stolper, flute Symphony in G Minor, op. 6, no. 6 Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) Allegro Andante più tosto Adagio Allegro molto Biographies Acclaimed British conductor Jane Glover has been Music of the Baroque’s music director since 2002. -

Verlorene Kirchen Dresdens Zerstörte Gotteshäuser Eine Dokumentation Seit 1938

Faktum Dresden Die sächsische Landeshauptstadt in Zahlen · 2015/2016 Verlorene Kirchen Dresdens zerstörte Gotteshäuser Eine Dokumentation seit 1938 Verlorene Kirchen Dresdens zerstörte Gotteshäuser Eine Dokumentation seit 1938 Dank Abb. 1: Rathaus und Evangelisch-reformierte Kirche, um 1910 Für umfangreiche Unterstützung oder für die Bereitstellung historischer Unterlagen danken die Autoren ■ Dr. Roland Ander ■ Eberhard Mittelbach, ehemaliger ■ Claudia Baum Sprengmeister ■ Pfarrer i. R. Johannes Böhme ■ Anita Niederlag, Landesamt für Denk- ■ Ulrich Eichler malpflege ■ Pfarrer Bernd Fischer, St.-Franziskus- ■ Rosemarie Petzold Xaverius-Gemeinde ■ Gerd Pfitzner, Amt für Kultur und ■ Martina Fröhlich, Bildstelle Stadt- Denkmalschutz planungsamt ■ Pfarrer i. R. Hanno Schmidt ■ Gerd Hiltscher, ehemaliger Küster der ■ Pfarrer Michael Schubert, St.-Pauli- Versöhnungskirche Gemeinde ■ Uwe Kind, Ipro Dresden ■ Dr. Peter W. Schumann, Gesellschaft ■ Stefan Kügler, Förderverein Trinitatis- zur Förderung einer Gedenkstätte für kirchruine den Sophienkirche Dresden e. V. ■ Cornelia Kraft ■ Friedrich Reichert, Stadtmuseum ■ Christa Lauffer, May Landschafts- ■ Pfarrer Klaus Vesting, Evangelisch- architekten reformierte-Gemeinde Abb. 2: Rathaus und Evangelisch-reformierte Kirche, nach 1945 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort 4 Die St.-Pauli-Kirche 40 Manfred Wiemer Joachim Liebers Einführung 5 Die Evangelisch-reformierte Kirche 44 Prof. Gerhard Glaser Dr. Manfred Dreßler † Die Sophienkirche 6 Die Trinitatiskirche 48 Dietmar Schreier und Manfred Lauffer † Dirk -

The American Bach Society the Westfield Center

The Eastman School of Music is grateful to our festival sponsors: The American Bach Society • The Westfield Center Christ Church • Memorial Art Gallery • Sacred Heart Cathedral • Third Presbyterian Church • Rochester Chapter of the American Guild of Organists • Encore Music Creations The American Bach Society The American Bach Society was founded in 1972 to support the study, performance, and appreciation of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach in the United States and Canada. The ABS produces Bach Notes and Bach Perspectives, sponsors a biennial meeting and conference, and offers grants and prizes for research on Bach. For more information about the Society, please visit www.americanbachsociety.org. The Westfield Center The Westfield Center was founded in 1979 by Lynn Edwards and Edward Pepe to fill a need for information about keyboard performance practice and instrument building in historical styles. In pursuing its mission to promote the study and appreciation of the organ and other keyboard instruments, the Westfield Center has become a vital public advocate for keyboard instruments and music. By bringing together professionals and an increasingly diverse music audience, the Center has inspired collaborations among organizations nationally and internationally. In 1999 Roger Sherman became Executive Director and developed several new projects for the Westfield Center, including a radio program, The Organ Loft, which is heard by 30,000 listeners in the Pacific 2 Northwest; and a Westfield Concert Scholar program that promotes young keyboard artists with awareness of historical keyboard performance practice through mentorship and concert opportunities. In addition to these programs, the Westfield Center sponsors an annual conference about significant topics in keyboard performance.