Northwestern Bohol, Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNDP Bohol Project

1 2 CONTENTS Executive summary 4 Introduction 6 Project objectives and outputs 8 Project Accomplishments Component 1 9 Component 2 12 Component 3 16 Cross-cutting themes 18 Good practices 19 Lessons learned 20 Visibility initiatives 21 Financial performance 22 Annexes Annex 1 : Accomplishments (vis-à-vis targets in the RRF) – Component 1 25 Annex 2: Accomplishments (vis-à-vis targets in the RRF) – Component 2 26 Annex 3: Accomplishments (vis-à-vis targets in the RRF) – Component 3 27 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Many local and international organizations, including UNDP, supported government authorities in responding to the 7.2 magnitude earthquake that struck Central Visayas, including the hardest-hit province of Bohol, in October 2013. Immediately after the earthquake, UNDP joined the multi-sectoral assessment which looked into the most urgent needs of the affected population. As the co-lead of the Early Recovery (ER) Cluster, UNDP zeroed in on the specific ER needs of the communities and formulated project interventions which could facilitate their early recovery and help establish the foundations for long-term development. With funding assistance of USD 800,000 from the Government of Japan, the project “Debris Management and Livelihood Support for areas affected by the Bohol Earthquake,” or the Bohol Early Recovery Project, was designed to benefit the ten (10) hardest hit municipalities in southwestern Bohol namely, Maribojoc, Antequera, Loon, Calape, Tubigon, Clarin, Inabanga, Sagbayan, Catigbian, and San Isidro. The project later expanded to include the nearby municipality of Carmen (component 1 only) upon the request of its municipal government for assistance in addressing the effects of the earthquake. -

From the Philippine Islands

THE VELIGER © CMS, Inc., 1988 The Veliger 30(4):408-411 (April 1, 1988) Two New Species of Liotiinae (Gastropoda: Turbinidae) from the Philippine Islands by JAMES H. McLEAN Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, U.S.A. Abstract. Two new gastropods of the turbinid subfamily Liotiinae are described: Bathyliontia glassi and Pseudoliotina springsteeni. Both species have been collected recently in tangle nets off the Philippine Islands. INTRODUCTION types are deposited in the LACM, the U.S. National Mu seum of Natural History, Washington (USNM), and the A number of new or previously rare species have been Australian Museum, Sydney (AMS). Additional material taken in recent years by shell fishermen using tangle nets in less perfect condition of the first described species has in the Philippine Islands, particularly in the Bohol Strait between Cebu and Bohol. Specimens of the same two new been recognized in the collections of the USNM and the species in the turbinid subfamily Liotiinae have been re Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris (MNHN). ceived from Charles Glass of Santa Barbara, California, and Jim Springsteen of Melbourne, Australia. Because Family TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 these species are now appearing in Philippine collections, they are described prior to completion of a world-wide Subfamily LIOTIINAE H. & A. Adams, 1854 review of the subfamily, for which I have been gathering The subfamily is characterized by a turbiniform profile, materials and examining type specimens in various mu nacreous interior, fine lamellar sculpture, an intritacalx in seums. Two other species, Liotina peronii (Kiener, 1839) most genera, circular aperture, a multispiral operculum and Dentarene loculosa (Gould, 1859), also have been taken with calcareous beads, and a radula like that of other by tangle nets in the Bohol Strait but are not treated here. -

TAKING ACTION in ASIAN CITIES Poverty Reduction and Environmental Management

Poverty reduction and environmental management: TAKING ACTION IN ASIAN CITIES Poverty reduction and environmental management: TAKING ACTION IN ASIAN CITIES Copyright - Engr. Maria Nenita R. Chiu, Municipal Planning and Development Coordinator, Municipality of Maribojoc ecoBUDGET Trademark is registered by ICLEI European Secretariat GmbH - Ms. Amor Maria J. Vistal, Executive Assistant to the Municipal Mayor, Municipality of Maribojoc - Engr. Joseph R. Anania, Municipal Planning and Development Coordinator, Municipality of Pilar Disclaimer - Engr. Ednardo A. Avenido, Municipal Planning and Development Coordinator, Municipality of Talibon This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European - Ms. Joannevit R. Avenido, Municipal Planning and Development Office Staff, Municipality of Talibon Union. The contents of this document are the sole products of Realising DReAMS for - Engr. Noel. C Mendaǹa, Municipal Planning and Development Coordinator, Municipality of Tubigon South and Southeast Asian Local Authorities and can under no circumstances be - Mrs. Yolanda L. Labella, Municipal Agriculturist, Municipality of Tubigon regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. - Ms. Rita Amor M. Narvasa, Planning Officer, Municipality of Tubigon European Commission Acknowledgement - Hon. Erico B. Aumentado (Deceased) Governor (2007 to 2010), Province of Bohol This project is funded by the European Union - Hon. Edgardo M. Chatto, Governor (2010 to Present), Province of Bohol - Hon. Concepcion O. Lim, Vice-Governor, Province of Bohol Visibility of funding - Hon. Abeleon R. Damalerio, Board Member and Project Senior Officer, Province of Bohol The Realising DReAMS project has been supported by the European Union Directorate-General - Ms. Coleen R. Montalba, Project Finance Officer, DReAMS Project Management Office (Bohol) - Mr. Anthony C. -

Part I ABATAN WATERSHED CHARACTERIZATION REPORT

Part I [Type text] Page 0 Abatan Watershed Characterization Report and Integrated Watershed Management Plan September 2010 Part I ABATAN WATERSHED CHARACTERIZATION REPORT I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND INFORMATION The Abatan Watershed is the third largest of the 11 major watershed networks that support water needs and other requirements of the island province of Bohol. It covers some 38,628 hectares or close to 9% of the province‟s total land area. It has three distinct land divisions, coastal, lowland and upland. The coastal areas are marine and not along the most of the river. Table 1. Municipalities and their barangays comprising the Abatan Watershed Municipality Barangay Percent Angilan, Bantolinao, Bicahan, Bitaugan, Bungahan, Can-omay, Canlaas, 1. Antequera Cansibuan, Celing, Danao, Danicop, Mag-aso, Poblacion, Quinapon-an, 100 Santo Rosario, Tabuan, Tagubaas, Tupas, Ubojan, Viga, and Villa Aurora Baucan Norte, Baucan Sur, Boctol, Boyog Sur, Cabad, Candasig, Cantalid, Cantomimbo, Datag Norte, Datag Sur, Del Carmen Este, Del Carmen Norte, 2. Balilihan 71 Del Carmen Sur, Del Carmen Weste, Dorol, Haguilanan Grande, Magsija, Maslog, Sagasa, Sal-ing, San Isidro, and San Roque 3. Calape Cabayugan, Sampoangon, and Sohoton 9 Alegria, Ambuan, Bongbong, Candumayao, Causwagan, Haguilanan, 4. Catigbian Libertad Sur, Mantasida, Poblacion, Poblacion Weste, Rizal, and 54 Sinakayanan 5. Clarin Cabog, Danahao, and Tubod 12 Anislag, Canangca-an, Canapnapan, Cancatac, Pandol, Poblacion, and 6. Corella 88 Tanday Fatima, Loreto, Lourdes, Malayo Norte, Malayo Sur, Monserrat, New 7. Cortes Lourdes, Patrocinio, Poblacion, Rosario, Salvador, San Roque, and Upper de 93 la Paz 8. Loon Campatud 1 9. Maribojoc Agahay, Aliguay, Busao, Cabawan, Lincod, San Roque, and Toril 39 10. -

Republic of the Philippines Region VII, Central Visayas

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Region VII, Central Visayas DIVISION OF BOHOL City of Tagbilaran April 28, 2017 DIVI SION MEMORANDUM No. 2O2. , s. 2017 TRAINING WORKSHOP ON CONTEXTUALIZING THE CURICULUM FOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLES EDUCATION(IPED) PART 3 To : PUBLIC SCHOOLS DISTRICT SUPERVISORS (PSDS)/OIC-PSDSs SCHOOL HEADS AND TEACHERS IMPLEMENTING IPED PROGRAM, IPED TECHNICAL WORKING GROUP AND ALL OTHER CONCERNS: 1. Per unnumbered Regional Memorandum dated April 17, 2017 there will be a Training Workshop on Contextualizing the Curriculum for Indigenous (IPED) Part 3 on May 2-5, 2017 at Crown Regency Hotel, Guadalupe Cebu City. First meal will be on lunch of May 2, 2017. 2. The following are the School Heads and teacher participants from this division: Name School/District Name School/District Nenita Alupit Taytay ES, Duero Virginia Estoce - Tutolan ES/Dauis Verona Ampo Taytay ES, Duero Saturnina Castro - Tutolan ES, Dauis Rosalia Ladica Taytay ES, Duero Agustina Doloritos - Tutolan ES, Dauis Ma. Grace Codilla BiabasES, Guindulman Merry Joy Cuadra - Tutolan ES, Dauis Romualda Aranay Biabas ES, Guindulman Donabel Datahan - Mariviles ES, Dauis Cristina Peligro Biabas ES, Guindulman Cerila Umas-as - Botoc ES, Loay Regie Mante Lundag ES, Pilar Hazel Leopando - Botoc ES, Loay Normelita Amonicio Lundag ES, Pilar Jupiter Maboloc- Div. Office Charlyn Balaba Lundag ES, Pilar 3. The following IP elder representatives are also invited as resource speakers. a.Decena Nida Salingay-Eskaya IP Representative b.Vilma Pauden - Ati IP Representative c.Edith Ligadong - Badjao Representative REPUBLIKANG PILIFINAS REPUBLIC OFTHE PHILIPPINES KAGAWARAN NG EDUKASYON DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION REHTVON VD, GITNANG V1SAYAS REGION VII, CENTRAL VISAYAS Sudlon, Lahug, Ccbu City MEMORANDUM To : Schools Division Superintendents of: Bohol Division Ceba City City of Naga From : JULIET A. -

Download 6.02 MB

Initial Environmental Examination January 2019 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Rehabilitation of Ilaya to Datag Access Road in Inabanga, Bohol Prepared by Municipality of Inabanga, Province of Bohol for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 03 December 2018 Year) The date of the currency equivalents must be within 2 months from the date on the cover. Currency unit – peso (PhP) PhP 1.00 = $ 0.019052 $1.00 = PhP 52.4864 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank BDC Barangay Development Council BUB Bottom-Up Budgeting CNC Certificate of Non-Coverage CSC Construction Supervision Consultant CSO Civil Society Organization DED Detail Engineering Design DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources DILG Department of Interior and Local Government DSWD Department of Social Welfare and Development ECA Environmentally Critical Area ECC Environmental Compliance Certificate ECP Environmentally Critical Project EHSM Environmental Health and Safety Manager EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIS Environmental Impact Statement EMB Environmental Management Bureau ESS Environmental Safeguards Specialist GAD Gender and Development IEE Initial Environmental Examination INREMP Integrated Natural Resources and Environment Management Project IP Indigenous People IROW Infrastructure Right of Way LGU Local Government Unit LPRAT Local Poverty Reduction Action Team MDC Municipal Development Council NAAQ National Ambient Air Quality Guidelines NCB National Competitive Bidding NECA Non-Environmental Critical -

LIST of PROJECTS ISSUED CEASE and DESIST ORDER and CDO LIFTED( 2001-2019) As of May 2019 CDO

HOUSING AND LAND USE REGULATORY BOARD Regional Field Office - Central Visayas Region LIST OF PROJECTS ISSUED CEASE AND DESIST ORDER and CDO LIFTED( 2001-2019) As of May 2019 CDO PROJECT NAME OWNER/DEVELOPER LOCATION DATE REASON FOR CDO CDO LIFTED 1 Failure to comply of the SHC ATHECOR DEVELOPMENT 88 SUMMER BREEZE project under RA 7279 as CORP. Pit-os, Cebu City 21/12/2018 amended by RA 10884 2 . Failure to comply of the SHC 888 ACACIA PROJECT PRIMARY HOMES, INC. project under RA 7279 as Acacia St., Capitol Site, cebu City 21/12/2018 amended by RA 10884 3 A & B Phase III Sps. Glen & Divina Andales Cogon, Bogo, Cebu 3/12/2002 Incomplete development 4 . Failure to comply of the SHC DAMARU PROPERTY ADAMAH HOMES NORTH project under RA 7279 as VENTURES CORP. Jugan, Consolacion, cebu 21/12/2018 amended by RA 10884 5 Adolfo Homes Subdivision Adolfo Villegas San Isidro, Tanjay City, Negros O 7/5/2005 Incomplete development 7 Aduna Beach Villas Aduna Commerial Estate Guinsay, Danao City 6/22/2015 No 20% SHC Corp 8 Agripina Homes Subd. Napoleon De la Torre Guinobotan, Trinidad, Bohol 9/8/2010 Incomplete development 9 . AE INTERNATIONAL Failure to comply of the SHC ALBERLYN WEST BOX HILL CONSTRUCTION AND project under RA 7279 as RESIDENCES DEVELOPMENT amended by RA 10884 CORPORATION Mohon, Talisay City 21/12/2018 10 Almiya Subd Aboitizland, Inc Canduman, Mandaue City 2/10/2015 No CR/LS of SHC/No BL Approved plans 11 Anami Homes Subd (EH) Softouch Property Dev Basak, Lapu-Lapu City 04/05/19 Incomplete dev 12 Anami Homes Subd (SH) Softouch Property -

Department of Education REGION VII - CENTRAL VISAYAS SCHOOLS DIVISION of DUMAGUETE CITY

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education REGION VII - CENTRAL VISAYAS SCHOOLS DIVISION OF DUMAGUETE CITY Office of the Schools Division Superintendent August 7, 2020 DIVISION MEMORANDUM No. 204, s. 2020 SIMPLIFIED CO-FACILITATION MANUAL FOR PARENTS TO : OIC, Asst. Schools Division Supt. Chiefs, CID and SGOD Education Program Supervisors Senior/Education Program Specialists Public Elementary and Secondary School Heads All others concerned 1. Learning in the new normal has presented an unprecedented challenge for instruction, particularly among parents. Along the issue, this office has developed a simplified co-facilitation manual which will aid parents in understanding better their own learners. 2. In view of such, all schools are directed to integrate the manual in the conduct of their parents and teachers’ meetings and orientation prior to the opening of classes. Schools may also print the same and distribute to parents for proper guidance. 3. Expenses relative thereto shall be charged against the school funds, subject to the accounting and auditing rules and regulations. 4. Immediate compliance to this Memorandum is desired. GREGORIO CYRUS R. ELEJORDE, Ed.D., CESO V Schools Division Superintendent Address: Taclobo, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental Telephone Nos.: (035) 421-2262/(035) 225-0603/(035) 523-6689 Email Address: [email protected] Republic of the Philippines Department of Education REGION VII - CENTRAL VISAYAS SCHOOLS DIVISION OF DUMAGUETE CITY Office of the Schools Division Superintendent Address: Taclobo, -

I. Region Vii - Central Visayas

I. REGION VII - CENTRAL VISAYAS I.1. BOHOL ISLAND STATE UNIVERSITY (CENTRAL VISAYAS STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND TECHNOLOGY) For general administration and support, and operations, as indicated hereunder .......................................... P 120,371,000 --------------- New Appropriations, by Program/Project ====================================== Current Operating Expenditures Maintenance and Other Personal Operating Capital Services Expenses Outlays Total A. PROGRAMS I. General Administration and Support/Operations P 95,765,000 P 24,606,000 P 120,371,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- Total, Programs 95,765,000 24,606,000 120,371,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- TOTAL NEW APPROPRIATIONS P 95,765,000 P 24,606,000 P 120,371,000 =============== =============== =============== Current Operating Expenditures Maintenance and Other Personal Operating Capital Services Expenses Outlays Total PROGRAMS AND ACTIVITIES I. General Administration and Support a. General Administration & Support Services P 25,989,000 P 9,993,000 P 35,982,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- Sub-Total, General Administration and Support 25,989,000 9,993,000 35,982,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- II. Operations a. Higher Education Services 69,776,000 14,613,000 84,389,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- Sub-Total, Operations 69,776,000 14,613,000 84,389,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- TOTAL PROGRAMS AND ACTIVITIES P 95,765,000 P 24,606,000 P 120,371,000 -

Bohol Emergency Contact List 25 October 2013

Bohol Emergency Contact List 25 October 2013 Organization Last First Cluster Title Cell Email Government DSWD National GUDMALIN Camilo CCCM, Food, Protection Asst. Secretary 0920-9485383 [email protected] OCD VII MORANTE Minda Regional Director [email protected] Crisis Management Team - Relief LGU Province QUIROG Liza Operation 0917-3246600 LGU Maribojoc EVASCO Leoncio Mayor 0928-5078279 LGU Loon LOPEZ Llyod Peter Mayor 0920-9012918 LGU Antequera PAHANG Jose Mario Mayor 0917-6335550 LGU Calape YU Sulpicio Mayor 0917-3090033 LGU Carmen TORIBIO Ricardo Francisco Mayor 0920-9669848 LGU Sagbayan SUAREZ Ricardo Mayor 0917-3042799 DepEd Superintendent (Bohol) BONGALOS Will Superitendent 0917-6309160 LGU Tugibon AMILA Marlon Mayor 0922-8495296 DSWD FO-VII SUBONG Grace Shelter Cluster Coordinator 0917-7120024 [email protected] LGU Province DAMALERIO II Alfonso Provincial Administrator 0917-3042306 [email protected] Crisis Management Team - Medical LGU Province CABAGNOT Reymoses Support 0916-7929825 LGU Alicia AYUBAN Marnilou Mayor 0929-4364046 LGU Clarin PIEZAS Allen Ray Mayor 0917-3041060 MSWDO Loon PALACIO Ma. Vilma Social Welfare Assistant 0939-2878389 MSWDO Loon MAGUINDANG Ma. Marnelli Focal Point 0917-3241272 OPSWD Bohol COMODAS Jesusa CAA-I 0919-6919691 OCD VII-Planning ALEMANIA Tash Information focal point 0946-3545827 [email protected] LGU Alburquerque TUNGOL Efren Mayor 0917-3038158 Organization Last First Cluster Title Cell Email LGU Baclayon UY Alvin Mayor 0917-3043930 LGU Balilihan CHATTO Dominisio Mayor 0917-3042738 -

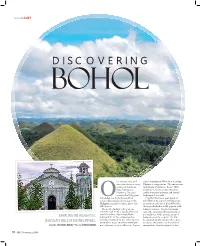

DISCOVERING Bohol

wanderLUST DISCOVERING Bohol ver the past 10 years I a week lounging on White Beach, asking have visited almost every Filipinos for suggestions. The answer was country in Southeast surprisingly unanimous: Bohol. With Asia, from Laos to promises of dreamy tropical beaches, Indonesia. But until cuddly miniature primates and surreal recently the Philippines landscapes, I was sold. had eluded me. To be honest, I had Frankly, I had never even heard of Onever really considered traveling to the Bohol before my trip to the Philippines. Philippines, mainly because I knew very Located a stone’s throw from Cebu City, little about it. the tropical island is wildly popular with Then, after fi nding a cheap promo domestic tourists. Despite remaining ticket through AirAsia, I suddenly found under the international tourist radar, it myself boarding a last-minute fl ight is actually one of the most frequented SAMPLING THE DELIGHTFUL to Cebu City. As the archipelago was destinations in the country. The few uncharted territory for me, I was clueless foreign visitors who venture there do so CHOCOLATE HILLS OF THE PHILIPPINES. about where to go, other than visiting the to explore the pristine coral reefs that WORDS JUSTINE LOPEZ | PHOTOS TONY KUEHN world-famous beaches of Boracay. I spent surround the island and give Bohol its 10 JPLUS November 23, 2014 wanderLUST reputation as one of the top 10 dive spots in place is so great, why had I never heard of it the world. before? And why don’t more people visit it? Because I’m not a diver, I came to check `I booked a hotel room in the quaint were surprisingly few tourists. -

The “Chocolate Hills” of Bohol (Philippines) Skrivnostni Kras: “Čokoladni Griči” Otoka Bohol (Filipini)

COBISS: 1.01 A MYSTERIOUS KARST: THE “CHOCOLATE HILLS” OF BOHOL (PHILIPPINES) SKRIVNOSTNI KRAS: “ČOKOLADNI GRIČI” OTOKA BOHOL (FILIPINI) Jean-Noël SALOMON1 Abstract UDC 911.2:551.435.8(599) Izvleček UDK 911.2:551.435.8(599) Jean-Noël Salomon: A Mysterious Karst: the “Chocolate Hills” Jean-Noël Salomon: Skrivnostni kras: “Čokoladni griči” otoka of Bohol (Philippines) Bohol (Filipini) A public showcase by the Philippine tourism authorities, and Glavni adut filipinske državne turistične organizacije, in to rightly so, are the “Chocolate Hills” of Bohol (Philippines), the z razlogom, so “Čokoladni griči” na otoku Bohol, ena najbolj strangest karst landform known. These numerous residual re- nenavadnih kraških pokrajin. Ti nenavadni reliefni ostanki so lief forms are so perfectly symmetrical that, in order to explain tako popolnoma simetrični, da se za razlago njihovega nasta- their existence, natural explanations are systematically sidelined nka izogiba naravnim procesom na račun legend in mitov, da by legends, myths and many so-called “scientific” explanations. niti ne omenimo številnih lažnoznanstvenih razlag. Ti kraški The object of many television broadcasts related to travel, these griči, pogosto predmet televizijskih oddaj o potovanjih, so karst hills are a particularly original example of mogotes tropi- posebni primer tropskega krasa z mogotami, ki so takorekoč cal karst; their almost “perfect” aspect had intrigued those who “popolne”, kar je povzročalo težave vsem, ki so se ukvarjali z have studied their formation and have given birth