Explaining Labor Union Support for Immigrants in Western Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OL-Sejlere Gennem Tiden

Danske OL-sejlere gennem tiden Sejlsport var for første gang på OL-programmet i 1900 (Paris), mens dansk sejlsport debuterede ved OL i 1912 (Stockholm) - og har været med hver gang siden, dog to undtagelser (1920, 1932). 2016 - RIO DE JANIERO, BRASILIEN Sejladser i Finnjolle, 49er, 49erFX, Nacra 17, 470, Laser, Laser Radial og RS:X. Resultater Bronze i Laser Radial: Anne-Marie Rindom Bronze i 49erFX: Jena Mai Hansen og Katja Salskov-Iversen 4. plads i 49er: Jonas Warrer og Christian Peter Lübeck 12. plads i Nacra 17: Allan Nørregaard og Anette Viborg 16. plads i Finn: Jonas Høgh-Christensen 25. plads i Laser: Michael Hansen 12. plads i RS:X(m): Sebastian Fleischer 15. plads i RS:X(k): Lærke Buhl-Hansen 2012 - LONDON, WEYMOUTH Sejladser i Star, Elliot 6m (matchrace), Finnjolle, 49er, 470, Laser, Laser Radial og RS:X. Resultater Sølv i Finnjolle: Jonas Høgh-Christensen. Bronze i 49er: Allan Nørregaard og Peter Lang. 10. plads i matchrace: Lotte Meldgaard, Susanne Boidin og Tina Schmidt Gramkov. 11. plads i Star: Michael Hestbæk og Claus Olesen. 13. plads i Laser Radial: Anne-Marie Rindom. 16. plads i 470: Henriette Koch og Lene Sommer. 19. plads i Laser: Thorbjørn Schierup. 29. plads i RS:X: Sebastian Fleischer. 2008 - BEIJING, QINGDAO Sejladser i Yngling, Star, Tornado, 49er, 470, Finnjolle, Laser, Laser Radial og RS:X. Resultater Guld i 49er: Jonas Warrer og Martin Kirketerp. 6. plads i Finnjolle: Jonas Høgh-Christensen. 19. plads i RS:X: Bettina Honoré. 23. plads i Laser: Anders Nyholm. 24. plads i RS:X: Jonas Kældsø. -

SOLING GUIDE 1981 CLASS and CHAMPIONSHIP \ SPECIFICATION RULES Length -Overall 8·20M Length-Waterline 6·10M

I SOLING GUIDE 1981 CLASS AND CHAMPIONSHIP \ SPECIFICATION RULES Length -Overall 8·20m Length-Waterline 6·10m Beam-Max ' 1·90m Av. Freeboard 0·54m Displacement 1,035 kg Keel Weight 580 kg Ballast Ratio 56% Mainsail Area · 13·6 m2 Jib 8·1 m2 Designer: Jan H. Linge ~OJJ. ~. ~· INTERNATIONAL SOLING ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONAL SOLING CLASS-HISTORY IN SHORT Designer: Jan Herman Linge. copies, a great success. Meeting of Members at Geneva, 1964 ·SOLING Prototype tested and evaluated. first race-series for Alpen Cup and Finnish Cup. At the 1965 ·First SOLING mould for GAP-production. meetings in London, November 1976, the Soling Class was re-elected to the Olympics in 1980 at Tallinn. A working 1966- Five SOLINGs from GAP-mould sailing trials. group was established for making Standard Soling Sailing 1966- Autumn: SOLING entered for the first Three-Man-Keel-Boat Instructions. trials at Kiel. 1967- 60 SOLINGs built. Racing in Scandinavia and U.S.A. First 1977- The activities - especially in launching new Solings - international regatta July 1967 (6 racesrat Copenhagen (17 very good. This 10th anniversary of the International Soling competed). First National Soling Association (NSA) and Class was celebrated in Norway - the country of the International Soling Association (ISA) launched. Second designer- at the World Championship. trials in Germany. - November 9th: The SOLING received 1978- The class suffered a very sad loss in the death of EYVIN international status. SCHIOTIZ, who had been secretary since the Soling 1968- First European Championship. About 300 SOLINGs built. became an International class. At short notice, Arnold van November: The International Soling Class was adopted for Altena of Holland kindly took over on a temporary basis the 1972-0iympics. -

Annual Report of the Certification Officer | 2013-2014

Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2013-2014 www.certoffice.org CERTIFICATION OFFICE FOR TRADE UNIONS AND EMPLOYERS’ ASSOCIATIONS Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2013-2014 www.certoffice.org © Crown Copyright 2014 First published 2014 ii The Rt Hon Dr Vince Cable MP Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills 1 Victoria Street London SW1H 0ET Sir Brendan Barber Chair of ACAS Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3JJ I am required by the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 to submit to you both a report on my activities as the Certification Officer during the previous reporting period. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2014. DAVID COCKBURN The Certification Officer 24 June 2014 iii Contents Page Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Lists of Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations 5 Entry in the lists and its significance 5 Unions and employers’ associations formed by an amalgamation 6 Trade unions and employers’ associations not on the lists (scheduled bodies) 6 Removal from the lists and schedules 6 Additions to the lists and schedules 8 The lists and schedules at 31 March 2014 8 Special register bodies 9 Changes of name of listed trade unions and employers’ associations 10 Definition of a trade union 11 Definition of an employers’ association 11 2 Trade Union Independence 13 The statutory provisions 13 Criteria 14 Applications, decisions, reviews and appeals 14 3 Annual Returns, Financial Irregularities -

For Unions the Future

the future for unions Tom Wilson This publication has been produced with the kind support of Russell Jones & Walker Solicitors. © No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing from Unions 21. Registered offi ce Unions 21 Swinton House 324 Gray’s Inn Road London WC1X 8DD Contents Foreword – Debate 4 Biography – Tom Wilson 5 Summary 5 Introduction 6 A 9-point plan for growth 7 Union membership 12 Like recruits like: the importance of occupation 13 Public versus private 16 Equality and gender: the feminisation of the unions 18 Education 20 The changing shape of the union movement 21 Vulnerable workers 22 Students and young workers 24 The unions themselves 25 Size: to merge or not to merge? 30 What makes a successful union? 33 Appendix 34 Debate Unions 21 exists to provide an ‘open space’ for discussion on the future of the trade union movement and help build tomorrow’s unions in the UK. We are mainly resourced by contributions from trade unions and others who work with trade unions that recognise we need to keep the movement evolving in an ever changing world. We encourage discussion on tomorrow’s unions through publications, conferences, seminars and similar activities. The Debate series of publications present opinions upon the challenges trade unions are facing, solutions they may consider and best practice they may adopt. These opinions are not endorsed by Unions 21, but are published by us to encourage the much needed, sensible and realistic debate that is required if the trade union movement is going to prosper. -

1991 Soling Worlds at the Rochester Yacht

\ 1991 so|_||\|<;. WOR LD CHAMPIONSHIPS ROCHESTER N Y n f ' afiél x%**§E-_ ff -my 5 .3; ,_ .,,__ ' ;. _ . *Qi §3f§` __ " S 31: ` ' .,`. ` is _,_ .:f S <1 'f 2 1 wow » §%»1 ~ ,;;,5.; ;§YT*" z_ , '» __ ' ` é%<'==iLSf_;' ;§ff=f1",.' Q ~¥~§;!_ ~ 1" if '2f»§~:" ~ :_ P f=~ ' fl :_ \ I? 2, '= ~ gy ' 'fi ,:\Yf%f@_;@§;. ; __ x ;;?>_¢>%=>=§ ¢ -_ ~ » _Q ~ 1, ~ ' ~ ~ 53 _ __ _ _ _¢ ~W '~ _ Q- f __ ,i ~ *_ §f,,f§§S¢§_% » ' . f _ j -"_ V Q Xxx. ~ ; _ 'S __ ;x~ ~ 3 ,__ S;<_;~' * » _.___ - _` _ ~ _ww S `.,,_ 13, : Q ».' . Aa ` af" » w = " '!_ "', 1 if ,_ ¢§»?f= 1 ";¥~_" ¥ 1 : ~ _ " Qé*"_'¢_ :_§T* yay ; ~ 5% v . T S5>';&;~ ~_'g-5, ` 'S :~ " _ , v, `I`i "S;»isé_e=_ _ ' SLS ~. " ' ' » S -9 ~ ,_;1 _» § _ fav -'»'*:=_@ W - » = _: S ¢ ' , " - SSS ~, S » ' _ 31, " " _~ L59 ..`» <~ ~ ' \= ` ' ,_ ' . S. ~ ~~;f' _ ,> S ,,~~~_»§~¢~ = ~ __ f?`fi - > ¢z_ _J L "W _ '2i,;¢}¢§ »~ ei ,. 1 ' *%`_ * M " , gs; ,, " S; _, Q _viii S : ' _4.__,~, ' _. _ ' ' MS " S " ° » __ %>='%i~~` J- »Mf';%f 22 _ ' . "_»:==S1~'*_ i " fre > '= E ~ fi '~ _ /M ; ' ~;;>Sf_'Tif';; » , ' ' ~ ) _ __ ff 3f*'~s,§_¢'*#'::s=»1_~~>¢~» ' ~ »' _ L ` *:§f<~"=,__,;._= _t' S' * > S._='§i;'Z>:5, 1' '= _ ff ~ þÿ';;e';" ¬~'f 121 ` "" S ' -1 ff: ;§ ==<<5; ~ fm- ` _ »» 7 S_ ~ _ *ww 11: __¢3i~__"""5w_~'1_j'*i7- _ ~~»1 ='._-';,!@:=¢\*¥"$§>»_ , ._ ,ff _ ` wk'_~ f ~ ~£~> _»f,,.;' .»» >\.-wma ;S;_; , mi";,_>':\-,';g:;_»;_s>,gg~=£-*#.-; » - - ~ ~f»,, ' , , _ f §_S,;~ . -

The Danish Immigrant Museum

The Danish Immigrant Museum An International Cultural Center Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, Protector ® Your visit to THE DANISH IMMIGRANT MUSEUM is a Journey . A LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT January 2008 did we do to deserve this”? As my four grandparents Dear Friends and immigrated separately to this emerging nation, I speculate what their Supporters of thoughts must have been. Certainly The Danish their feelings must have been mixed. Immigrant Museum, Probably immense sadness at leaving family knowing they may never n calendar year 2008, The Danish see them again. I suspect there was IImmigrant Museum celebrates its anxiety at how they would cope in the 25th anniversary. Over the past 25 new world probably not knowing the years, much has been accomplished. language. There must have been great anticipation as to what opportunities A tremendous thank you goes to the Marc L. Petersen, President many dedicated people, volunteers and they would fi nd. The questions and staff, who have made this possible. Pat speculation could go on and on, but challenges of the future, we must yourself on the back as without you we all know courage had to be a have a fi rm foundation upon which there would be no national museum strong part of the constitution of the to build. We need both your fi nancial in the heart of the continent. Our immigrant striking out to a new life in and volunteer support. Certainly Danish heritage would not have been an unfamiliar world. membership renewal and recruitment preserved to the extent it is today The immigrant experiences of the is a key way to assist. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 171. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 13.Mai 2016 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 1 Gesetzentwurf der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Einstufung der Demokratischen Volksrepublik Algerien, des Königreichs Marokko und der Tunesischen Republik als sichere Herkunftsstaaten Drs. 18/8039 und 18/8311 Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 572 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 58 Ja-Stimmen: 424 Nein-Stimmen: 145 Enthaltungen: 3 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 13.05.2016 Beginn: 10:05 Ende: 10:08 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. André Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Iris Eberl X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Klaus-Peter Flosbach X Seite: 3 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. -

1989-Christmas

TOE BBITISB DRAGON ASSOCIATION 1989/90 CBRISTIIAS NEWSLETTER IN TBlS ISSUE Fixture List 1989 Season Reports 4 - 16 East Coast Championship South Coast Championship Edinburgh O..p 6 War ld Championship 7 - 14 Scottish Championship 15 1989 Gold O..p - Travemunde 16 From the Hon . Sec retary · s Desk 18 - 19 Notice of 1990 Annual General Meeting and Dinner 20 Accounts for the year ended 31st October 1989 21 - 22 0\airman' s Report 23 Selection procedure for European and World Championship events 25 - 26 Fleet Reports 27 - 34 Numerical list of DrAKOnS of B.D.A. .....bers 35- 38 Boats for sale 39 Notice Board 39 Membership Details AmendiDent Form 40 Form of APplication for Membership of B.D.A. 41 UST ~ ADYEBI"ISEliS North Sails Beefeater Gin 8 Harken 17 Hood Sails 24 St .Georce' s Dragons Ltd 34 Petticrow Boatyard Back Cover Rats ey &. l.apthorn Inside Back Cover Cover photocraph by Janet Harber ••••• FIXTURE LIST ••••• 1990 .._ (All "Q.oalifying" events) East Coast Cballlpionship 5th - 7th llay Levi.ncton South Coast Cballlpionship 26th - 28th llay Cowes Northent Area Championship 2nd l 3rd June Bangor , N. I. Edinburch O..p 16th - 22nd June Cowes Overseas Australia Prince Philip Cup 28th Dec ' 89 - ll th Jan' 90 Perth, WA Austria Austrian Championship 19th - 24th Aug Attersee Belgium North Sea Championship 16th/17th and 23rd/ 24th June Os tend Belgium Open Championship 11th - 15th Aug Os tend Denmark Danis h Championship 27th - 30th June France Vasco de Gama 14th - 21st April Arca.cbon Coupes des Q.Ji llards des Sports 28th April - lst llay -

OLYMPIC GAMES MOSCOW July 19 - August 03, 1980

Y.E.A.H. - Young Europeans Active and Healthy OLYMPIC GAMES MOSCOW July 19 - August 03, 1980 USA vs Soviet Union = boycott respective National Olympic Committees . Some of these teams that marched under flags other than their national flags were depleted by boycotts by individual athletes, while some The 1980 Summer Olympics, officially athletes did not participate in the march. The known as the Games of the XXII impact of the boycott was mixed. Some events, Olympiad ( Russian : Igry XXII Olimpiady ), took such as swimming, track and field, boxing, part in Moscow , Soviet Union , in present- basketball, diving, field hockey and equestrian day Russia . sports, were hard hit. Athletes from 25 countries won Olympic gold and competitors from 36 The 1980 Games were the first Olympic countries became Olympic medalists. Italy won Games to be staged in Eastern Europe , and four times more gold medals than they won in remain the only Summer Olympics held there, as Montreal and France multiplied its gold medal well as the first Olympic Games to be held in tally by three. Romania won more gold medals a Slavic language -speaking country. They were than it had at any previous Olympics. In terms of also the first Olympic Games to be held in a total medals, the Moscow Olympics was Ireland's socialist country, and the only Summer Games to most successful games since Melbourne 1956 be held in such a country until 2008 (winning 2 medals). The same was true for Great in Beijing , China . Britain. " Third World " athletes qualified for more events and took more medals than they did at any The only two cities to bid for the 1980 previous Olympics. -

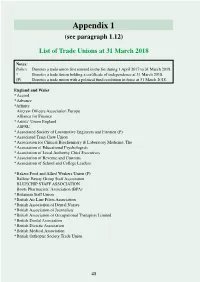

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

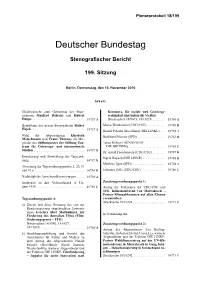

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a) -

Maersk Drilling in Australia in July 1982 Maersk Drilling Opened Its Office in Perth on the West Coast of Australia

The Danish Shipowners' Association was founded on January 17, 1884, under the name of "Dampskibsrhederi-Foreningen". At the time Danish shipowners were not awfully interested in the Association, which remained small at first. Today the Association counts most of the major shipping companies in Denmark among its members, and in a very effective way it looks after the interests of the third largest export industry in this country: shipping. The Association enjoys excellent, well-established relations with its own ministry, the Ministry of Industrial Affairs, and with other ministries and authorities, particularly the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Moreover, the MÆRSK organization co-operates well with various maritime associations and with the world at large wherever the ships operate; it maintains contacts with and connections to shipping organizations and authorities in other countries, to POST the UN, to NATO, and other international organizations. I believe that I am justified in saying that the Danish Shipowners' Associa- tion is respected for its work, both nationally and internationally, and it is always a pleasure to be reminded that the delegates of the Danish Published by A.P. Møller, Copenhagen Shipowners' Association fight well all over the world to ensure that the Editor: Einar Siberg world's needs for transport at sea may be satisfied without constricting ties. Printers: Dansk Kliché Fabrik 70 per cent of our planet is covered with water and almost 80 per cent of all international commerce is sea-borne, so there is good reason to fight to ensure that ships from Danish companies will retain their importance on the oceans and in the harbours of the world.