Using an Astrolabe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Science LR 2711

A Scientific Response to the Chester Beatty Library Collection Contents The Roots Of Modern Science A Scientific Response To The Chester Beatty Library Collection 1 Science And Technology 2 1 China 3 Science In Antiquity 4 Golden Age Of Islamic Science 5 Transmission Of Knowledge To Europe 6 A Scientific Response To The Chester Beatty Library Collections For Dublin City Of Science 2012 7 East Asian Collections The Great Encyclopaedia of the Yongle Reign (Yongle Dadian) 8 2 Phenomena of the Sky (Tianyuan yuli xiangyi tushuo) 9 Treatise on Astronomy and Chronology (Tianyuan lili daquan) 10 Illustrated Scrolls of Gold Mining on Sado Island (Sado kinzan zukan) 11 Islamic Collections Islamic Medicine 12 3 Medical Compendium, by al-Razi (Al-tibb al-mansuri) 13 Encyclopaedia of Medicine, by Ibn Sina (Al-qanun fi’l-tibb) 14 Treatise on Surgery, by al-Zahrawi (Al-tasrif li-man ‘ajiza ‘an al-ta’lif) 15 Treatise on Human Anatomy, by Mansur ibn Ilyas (Tashrih al-badan) 16 Barber –Surgeon toolkit from 1860 17 Islamic Astronomy and Mathematics 18 The Everlasting Cycles of Lights, by Muhyi al-Din al-Maghribi (Adwar al-anwar mada al-duhur wa-l-akwar) 19 Commentary on the Tadhkira of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi 20 Astrolabes 21 Islamic Technology 22 Abbasid Caliph, Ma’mum at the Hammam 23 European Collections European Science of the Middle Ages 24 4 European Technology: On Military Matters (De Re Militari) 25 European Technology: Concerning Military Matters (De Re Militari) 26 Mining Technology: On the Nature of Metals (De Re Metallica) 27 Fireworks: The triumphal -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance

Academia Europaea 19th Annual Conference in cooperation with: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Ministerio de Cultura (Spain) “The Dialogue of Three Cultures and our European Heritage” (Toledo Crucible of the Culture and the Dawn of the Renaissance) 2 - 5 September 2007, Toledo, Spain Chair, Organizing Committee: Prof. Manuel G. Velarde The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance M. Heydari-Malayeri Paris Observatory Summary This paper aims at presenting a brief overview of astronomical exchanges between the Eastern and Western parts of the Islamic world from the 8th to 14th century. These cultural interactions were in fact vaster involving Persian, Indian, Greek, and Chinese traditions. I will particularly focus on some interesting relations between the Persian astronomical heritage and the Andalusian (Spanish) achievements in that period. After a brief introduction dealing mainly with a couple of terminological remarks, I will present a glimpse of the historical context in which Muslim science developed. In Section 3, the origins of Muslim astronomy will be briefly examined. Section 4 will be concerned with Khwârizmi, the Persian astronomer/mathematician who wrote the first major astronomical work in the Muslim world. His influence on later Andalusian astronomy will be looked into in Section 5. Andalusian astronomy flourished in the 11th century, as will be studied in Section 6. Among its major achievements were the Toledan Tables and the Alfonsine Tables, which will be presented in Section 7. The Tables had a major position in European astronomy until the advent of Copernicus in the 16th century. Since Ptolemy’s models were not satisfactory, Muslim astronomers tried to improve them, as we will see in Section 8. -

Al-Kindi, a Ninth-Century Physician, Philosopher, And

AL-KINDI, A NINTH-CENTURY PHYSICIAN, PHILOSOPHER, AND SCHOLAR by SAMI HAMARNEH FROM 9-12 December, I962, the Ministry of Guidance in Iraq celebrated the thousandth anniversary of one of the greatest intellectual figures of ninth century Baghdad, Abui Yuisuf Ya'qiib ibn Ishaq al-Kind? (Latin Alkindus).1 However, in the aftermath ofthis commendable effort, no adequate coverage of al-Kindl as a physician-philosopher ofardent scholarship has, to my knowledge, been undertaken. This paper, therefore, is intended to shed light on his intel- lectual contributions within the framework of the environment and time in which he lived. My proposals and conclusions are mainly based upon a study of al-Kindi's extant scientific and philosophical writings, and on scattered information in the literature of the period. These historical records reveal that al-Kindi was the only man in medieval Islam to be called 'the philosopher of the Arabs'.2 This honorary title was apparently conferred upon him as early as the tenth century if not during his lifetime in the ninth. He lived in the Abbasids' capital during a time of high achievement. As one of the rare intellectual geniuses of the century, he con- tributed substantially to this great literary, philosophic, and scientific activity, which included all the then known branches of human knowledge. Very little is known for certain about the personal life of al-Kind?. Several references in the literary legacy ofIslam, however, have assisted in the attempt to speculate intelligently about the man. Most historians of the period confirm the fact that al-Kindl was of pure Arab stock and a rightful descendant of Kindah (or Kindat al-Muliuk), originally a royal south-Arabian tribe3. -

Origins of Astrolabe Theory the Origins of the Astrolabe Were in Classical Greece

What is an Astrolabe? The astrolabe is a very ancient astronomical computer for solving problems relating to time and the position of the Sun and stars in the sky. Several types of astrolabes have been made. By far the most popular type is the planispheric astrolabe, on which the celestial sphere is projected onto the plane of the equator. A typical old astrolabe was made of brass and was about 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter, although much larger and smaller ones were made. Astrolabes are used to show how the sky looks at a specific place at a given time. This is done by drawing the sky on the face of the astrolabe and marking it so positions in the sky are easy to find. To use an astrolabe, you adjust the moveable components to a specific date and time. Once set, the entire sky, both visible and invisible, is represented on the face of the instrument. This allows a great many astronomical problems to be solved in a very visual way. Typical uses of the astrolabe include finding the time during the day or night, finding the time of a celestial event such as sunrise or sunset and as a handy reference of celestial positions. Astrolabes were also one of the basic astronomy education tools in the late Middle Ages. Old instruments were also used for astrological purposes. The typical astrolabe was not a navigational instrument although an instrument called the mariner's astrolabe was widely used. The mariner's astrolabe is simply a ring marked in degrees for measuring celestial altitudes. -

Science and Technology in Medieval Islam

Museum of the History of Science Science and Islam Introduction to Astronomy in Islam Science and Learning in Medieval Islam • Early Islamic teaching encouraged the pursuit of all knowledge that helped to improve people’s lives • Muslims translated important works from ancient Greece and Egypt - Arabic became the international language of scholarship • Huge libraries were established in big cities like Baghdad, Cairo and Damascus Astronomy Astronomy was important to Muslims for practical reasons: • Observations of the sun and moon were used to determine prayer times and an accurate calendar • Astronomical observations were important for purposes of navigation • Astronomical observations were import for the practice of astrology Raj Jai Singh II’s observatory (C18th) in Jaipur, India Large observatories were established and new instruments such as the astrolabe were developed Ottoman observatory 1781 Photograph: The Whipple Museum, Cambridge The quadrant The quadrant is an observational instrument used to measure the angle or altitude of a celestial object. Horary quadrants also had markings on one side that would enable the user to calculate the time of day. Armillary sphere The armillary sphere was a model used to demonstrate the motions of the celestial sphere (stars) and the annual path of the sun (the ecliptic). It could also be used to demonstrate the seasons, the path of the sun in the sky for any day of the year, and to make other astronomical calculations. Early Islamic models were based on a model of the Universe established by Ptolemy in which the Earth was placed at the centre. The astrolabe The astrolabe was a type of astronomical calculator and were developed to an extraordinary level of sophistication by early Muslim scholars. -

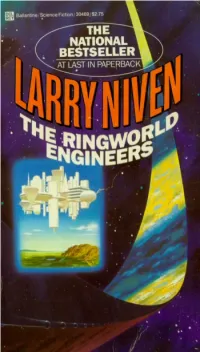

Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven PART ONE CHAPTER 1 UNDER the WIRE

Ringworld 02 Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven PART ONE CHAPTER 1 UNDER THE WIRE Louis Wu was under the wire when two men came to invade his privacy. He was in full lotus position on the lush yellow indoor-grass carpet. His smile was blissful, dreamy. The apartment was small, just one big room. He could see both doors. But, lost in the joy that only a wirehead knows, he never saw them arrive. Suddenly they were there: two pale youths, both over seven feet tall, studying Louis with contemptuous smiles. One snorted and dropped something weapon-shaped in his pocket. They were stepping forward as Louis stood up. It wasn't just the happy smile that fooled them. It was the fist-sized droud that protruded like a black plastic canker from the crown of Louis Wu's head. They were dealing with a current addict, and they knew what to expect. For years the man must have had no thought but for the wire trickling current into the pleasure center of his brain. He would be near starvation from self-neglect. He was small, a foot and a half shorter than either of the invaders. He — As they reached for him Louis bent far sideways, for balance, and kicked once, twice, thrice. One of the invaders was down, curled around himself and not breathing, before the other found the wit to back away. Louis came after him. What held the youth half paralyzed was the abstracted bliss with which Louis came to kill him. Too late, he reached for the stunner he'd pocketed. -

The Arabic-Latin Translators – Natural Science and Philosophy

CHARLES BURNETT List of Publications Books, and articles over 100 pages long Articles and pamphlets, arranged thematically, and in chronological order within each topic The Arabic-Latin Translators – Natural Science and Philosophy – Astronomy and Astrology - Medicine and Psychology – Magic and Divination – Arithmetic and Geometry – Anglo- Norman Science and Learning in the Twelfth Century – Peter Abelard and the French Schools – Music – Contacts between the West and the Far East – Miscellaneous – Reviews (selection) List of editions of Latin texts in books and articles above (Please note that some diacritical markings are missing) Books, and articles over 100 pages long: 1. Hermann of Carinthia, De essentiis, critical edition, translation and commentary, Leiden, 1982, 385 pp. (reviews in Speculum, 1984, pp. 911–3, Cahiers de civilisation médiévale, 28, 1985, p. 685, Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch, 20, 1985, pp. 287–90, Deutsches Archiv, 41, 1985, p. 255, Rivista di storia della filosofia, 2, 1984, pp. 349–51, Bulletin de théologie ancienne et médiévale, 14, 1989, p. 695). 2. ‘A Checklist of the Manuscripts Containing Writings of Peter Abelard and Heloise and Other Works Closely Associated with Abelard and his School’, Revue d’histoire des textes, 14–15, 1984–5, pp. 183–302 (with David Luscombe and Julia Barrow). 3. Pseudo-Bede, De mundi celestis terrestrisque constitutione: a Treatise on the Universe and the Soul, edition, translation and commentary, Warburg Institute Surveys and Texts 10, London, 1985. 88 pp. (reviews in Isis, 77, 1986, pp. 182–3, Revue d’histoire ecclésiastique, 81, 1986, p. 742, Ambix, 33, 1986, p. 155, Journal of the History of Astronomy, 19, 1988, pp. -

Universal Astrolabe

The Production Guide for the Zarqaliyya (Universal Astrolabe) in the Work of Abu al-Hasan al-Marrakushi Atilla Bir* Saliha Bütün** Mustafa Kaçar*** Âdem Akın**** Translated by Beyza Akatürk***** and Sena Aydın****** Abstract: One of the greatest astronomers of the 13th century, Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥasan al-Marrākushī is the author of Jāmiʿ al-mabādī’ wa-l-ghāyāt fī ʿilm al-mīqāt (An A to Z of Astronomical Timekeeping) which includes the production and operation guides for many astronomical instruments. This study translates the production guide Zarqāliyya, examines the working principle of this instrument, and presents a mathematical interpretation for current readers. A standard astrolabe provides measurements by means of disks produced separately for the different latitudes. The particular disk we examine in this article was developed by the Andalusian astronomer al-Zarqālī (d. 493/1100), is named zarqāliyya, and is known as ṣafīḥa in the West. This disk is peculiar to Islamic astronomy and enables measurement for any latitude. At present, this astrolabe is qualified as universal for being operational independent of latitude. Marrākushī’s discussion of this universal disk zarqāliyya in his time is an epitome for the understanding of the transmission and circulation of knowledge in the scientific environment of Islam, and the current article evaluates this aspect. This article includes the subject and importance of Marrākushī’s monumental work, its modern presentations, and the mathematical explanations of the universal astrolabe’s stereographic projection. It additionally provides the formulations necessary for constructing this astrolabe and presents drawings based on these relations using the Paris edition of the manuscript registered as Or. -

PDF-1 5 May/June 2019 2019 May/June Cedrus Libani

MAY JUNE 2019 6 Cedrus libani Forever? 14 Astrolabe 8SJUUFOBOEQIPUPHSBQIFECZ Sheldon Chad Tech Made … The cedars of Lebanon are symbols of the country itself, a living metaphor of both majestic Not So Easy beauty and endurance that has been tested by empire after axe-wielding empire. But few 8SJUUFOCZ Lee Lawrence cedars remain, and their survival is challenged by warming temperatures and the insects that 1IPUPHSBQITBOEWJEFPCZ David H. Wells follow. Reforestation is bringing new trees to higher, colder altitudes as activists work to *MMVTUSBUJPOTCZ Ivy Johnson extend preserves and biologists look to genetics for adaptations. Even our author pitches in and volunteers a handful of 24-year-old cedar seed cones for analysis—all to keep Cedrus libani About the size of a tablet computer, growing in the hills as well as in the hearts of Lebanon. astrolabes were tools of astronomers, surveyors and navigators, to name a few. But using them took a lot more than typing, tapping and swiping. OnlineCLASSROOM GUIDE 2FIRSTLOOK 4FLAVORS We distribute AramcoWorld in print and online to increase cross-cultural understanding by broadening knowledge of the histories, cultures and geography of the Arab and Muslim worlds and their global connections. aramcoworld.com Front Cover:&BDIBTUSPMBCFTGSPOUQMBUFJTFUDIFEXJUIMJOFTUIBUIFMQDBMDVMBUFTVOSJTF May/June 2019 TVOTFUBOEDFMFTUJBMDPPSEJOBUFTCZSPUBUJOHUIFDBMJCSBUFESFUFPWFSUIFN1IPUP"MBNZ Vol. 70, No. 3 /BWBM.VTFVNPG.BESJE Back Cover:*OUIFNPVOUBJOTPG-FCBOPO DFEBSTEFQFOEPOUIFDPMEPGXJOUFSUPCSFBLPQFO UIFJSTFFET1IPUPCZ(FPSHF"[BS -

History of Islamic Science

History of Islamic Science George Sarton‟s Tribute to Muslim Scientists in the “Introduction to the History of Science,” ”It will suffice here to evoke a few glorious names without contemporary equivalents in the West: Jabir ibn Haiyan, al-Kindi, al-Khwarizmi, al-Fargani, Al-Razi, Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Battani, Hunain ibn Ishaq, al-Farabi, Ibrahim ibn Sinan, al-Masudi, al-Tabari, Abul Wafa, ‘Ali ibn Abbas, Abul Qasim, Ibn al-Jazzar, al-Biruni, Ibn Sina, Ibn Yunus, al-Kashi, Ibn al-Haitham, ‘Ali Ibn ‘Isa al- Ghazali, al-zarqab,Omar Khayyam. A magnificent array of names which it would not be difficult to extend. If anyone tells you that the Middle Ages were scientifically sterile, just quote these men to him, all of whom flourished within a short period, 750 to 1100 A.D.” Preface On 8 June, A.D. 632, the Prophet Mohammed (Peace and Prayers be upon Him) died, having accomplished the marvelous task of uniting the tribes of Arabia into a homogeneous and powerful nation. In the interval, Persia, Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, the whole North Africa, Gibraltar and Spain had been submitted to the Islamic State, and a new civilization had been established. The Arabs quickly assimilated the culture and knowledge of the peoples they ruled, while the latter in turn - Persians, Syrians, Copts, Berbers, and others - adopted the Arabic language. The nationality of the Muslim thus became submerged, and the term Arab acquired a linguistic sense rather than a strictly ethnological one. As soon as Islamic state had been established, the Arabs began to encourage learning of all kinds. -

Life and Activity of Nasir Al-Din Al-Tusi

http://www.hst-journal.com Історія науки і техніки 2020, том 10, випуск 2 History of science and technology, 2020, vol. 10, issue 2 DOI:10.32703/2415-7422-2020-10-2-353-367 UDC 51(091) Maryam Seyidbeyli Institute of the History of Science Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences 115, Huseyn Javid Avenue, Baku, Azerbaijan e-mail: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6827-5885 Life and activity of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi Abstract. At the beginning of the VII century in the political life of the Near and Middle East, fundamental changes have taken place. The Arabs conquered a colossal territory, which included the lands of Iran, North Africa, North-West India, the Asian provinces of Byzantium, most of the former Roman Empire. In the conquered cities of the caliphate, observatories, madaris, libraries were built. At the end of VII century, the first scientific center, an academy, the House of Wisdom, was founded in Baghdad, in which scholars who spoke different languages were assembled. Here the translation and commentary activity were very developed, the main works of ancient thought, such as the writings of Aristotle, Ptolemy were published in the 9th century in the Arabic- speaking world. For two centuries from 750 to 950 years, the works of ancient authors on philosophy, mathematics, medicine, alchemy, and astronomy were translated into Arabic, which indicates the high scientific potential of that time in the East. At the same time, in the XII century, Ibn Rushd composed 38 commentaries on the works of Aristotle, the “Republic” of Plato, the treatise “On the Mind” of Alexander of Aphrodisias, which subsequently had an important influence on the work of Nasir al- Din al-Tusi.