(Raymond) • Neo Chin Kai, Andy Module

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dealing with Life’S Issues a Buddhist Perspective

Dealing with Life’s Issues A Buddhist Perspective B Ven. Thubten Chodron Published for Free Distribution Only Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery Dharma Propagation Division Awaken Publishing and Design 88 Bright Hill Road Singapore 574117 Tel: (65) 6849 5342 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.kmspks.org 1st Edition, January 2008 2nd reprint of 5,000 copies, April 2008 ISBN-13: 978-981-05-9395-7 EISSUES-0102-0408 © Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery Cover design: BigstockPhoto.com@rgbspace Although reprinting of our books for free distribution is encouraged as long as the publication is reprinted in its entirety with no modifications, including this statement of the conditions, and credit is given to the author and the publisher, we require permission to be obtained in writing, to ensure that the latest edition is used. Printed by Zheng Yong Binding (S) Pte Ltd Tel: (65) 6275 6228 Fax: (65) 6275 6338 Please pass this book around should you feel that you do not need it anymore. As the Buddha taught, the gift of Truth excels all other gifts! May all have the chance to know the Dharma. It is very, very rare for one to have a precious human life and still be able to encounter the Buddha-Dharma, therefore please handle this book with utmost respect and care. Printed in Singapore on 100% recycled paper. Cover is printed using paper manufactured from 55% recycled fibre and 45% pulp from responsibly managed forests. Contents Preface M v m Romantic Love & Marriage M 1 m Dharma & the Family M 14 m Dharma Guidance on World Events M 30 m Dharma & Terminal Illness M 67 m Dharma & Suicide M 103 m Dharma & the Prison: Making Friends with Ourselves M 127 m Dear Reader, If you wish to share the production costs of this and many other beautiful Dharma Books and CDs for free distribution, so that more people can be touched by the beauty of Dharma and be inspired to live a happy and meaningful life, please photocopy the sponsorship form at the back of this book, fill in your particulars and return it to us. -

2014 Multi-Faith Forum Activity Journal

1 Name : Galvihara Seated Image of the Buddha Time : 12th Century A.D. Location : Polonnaruwa (North Central Province-Sri Lanka) Founder : King Parakramabahu A Harmonious World Begins with Education 2558th Vesak Day Celebration: Learning from the Buddha's Inspirational Teachings Resolving Conflicts and Facilitating Peace and Security................................ 4 Religion and its Teachings are the Most Important Education for All Humanity...................................... 5 Religious Unity and Religious Education Can Facilitate World Peace...................................................... 5 Establishing a Religious Sacred City to Realize Religious Education....................................................... 8 Establishing a Multifaith University and Strengthening Religious Education and Religious Exchange.. 8 Wonderful New Development in the Revival of Religious Education in Indonesia.................................. 9 Indonesian Guest Photos............................................................................................................................ 11 2 “What Should We Do When Hearts are Corrupted and Society is in Chaos? —On Toowoomba, Australia as a Model City of Peace and Harmony........ 16 Unkind Human Mindset is the Root of the Chaotic Society...................................................................... 17 Religious Education is Crucial in Resolving World Crises........................................................................ 19 Cooperation between Religions is the Critical Step.................................................................................. -

Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities 469190 789811 9 Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore

Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities Inter-religious harmony is critical for Singapore’s liveability as a densely populated, multi-cultural city-state. In today’s STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS world where there is increasing polarisation in issues of race and religion, Singapore is a good example of harmonious existence between diverse places of worship and religious practices. This has been achieved through careful planning, governance and multi-stakeholder efforts, and underpinned by principles such as having a culture of integrity and innovating systematically. Through archival research and interviews with urban pioneers and experts, Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities documents the planning and governance of religious harmony in Singapore from pre-independence till the present and Communities Practices Spaces, Religious Harmony in Singapore: day, with a focus on places of worship and religious practices. Religious Harmony “Singapore must treasure the racial and religious harmony that it enjoys…We worked long and hard to arrive here, and we must in Singapore: work even harder to preserve this peace for future generations.” Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore. Spaces, Practices and Communities 9 789811 469190 Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities Urban Systems Studies Books Water: From Scarce Resource to National Asset Transport: Overcoming Constraints, Sustaining Mobility Industrial Infrastructure: Growing in Tandem with the Economy Sustainable Environment: -

Chapter 7 an Insider's Research Into Buddhist History1

Chapter 7 An Insider’s Research into Buddhist History1 Jack Meng-Tat Chia Buddhism is one of the major religions in present-day Singapore. In fact, one can easily notice the rich diversity of different Buddhist traditions – Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana – co-existing and interacting in our global city-state. According to the 2000 census, Buddhism is both the majority and fastest growing religion in Singa- pore.2 Despite this, there are only a handful of studies on the history of Buddhism in Singapore.3 As I have argued in a recent essay, while these previous research provide a useful introduction to change and continuity in the history of the religion, they tend to be overly ambitious and broad in their scope. Rather than focusing on specific themes or providing in-depth case studies of Buddhist practices, organizations and personalities, these studies examined the religion in an overarching manner. As a result, they are seldom able to fully explore and analyze the multi-faceted and complex issues surrounding Buddhism in the history of Singapore.4 For this reason, research on specific themes and case studies in the religion remain to be done. 1 I am grateful to C. C. Chin, Kuah Khun Eng, Loh Kah Seng, and Soh Gek Han for their helpful comments. Pseudonyms are used in this paper. 2 Singapore, Census of Population 2000 (Singapore: Department of Statistics, 2000). 3 See Shi Chuanfa 释传发, Xinjiapo Fojiao fazhan shi 新加坡佛教发展史[A History of the Development of Buddhism in Singapore] (Singapore: Xinjiapo Fojiao Jushilin, 1997); Y. D. Ong, Buddhism in Singapore: A Short Narrative History (Singapore: Skylark Publications, 2005); Hue Guan Thye 许原泰, Xinjiapo Fojiao: Chuanbo yange yu moshi 新加坡佛教: 传播沿 革与模式 [Buddhism in Singapore: Propagation, Evolution and Practice] (M.A. -

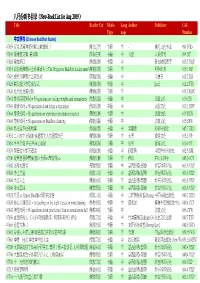

八月份新书目录(((New-Book(New-Book List for Aug 2019) Title Reader Cat Media Lang Author Publisher Call Type Uage Number 中 文 佛(Chinese 书 Buddhist Books) 47655 汉月法藏禅师珍稀文献选辑

八月份新书目录(((New-Book(New-Book List for Aug 2019) Title Reader Cat Media Lang Author Publisher Call Type uage Number 中 文 佛(Chinese 书 Buddhist Books) 47655 汉月法藏禅师珍稀文献选辑. 1 佛书总类 书籍 中 - 佛光文化事业 091 FGD 47634 惭愧僧文集. 第10集 佛书总类 书籍 中 大愿 人乘佛刊 094 DY 47610 瑜伽焰口 佛教仪制 书籍 中 新加坡报恩寺 615.3 YQY 47615 新加坡佛教居士林课诵本 = The Singapore Buddhist Lodge sutra book佛教仪制 书籍 中 柯华印务 615.1 JSP 47624 授式叉摩那六法戒仪式 佛教仪制 书籍 中 义德寺 611.2 JSS 47625 剃发授沙弥尼戒仪式 佛教仪制 书籍 中 [s.n.] 611.2 TFS 47626 比丘尼说戒仪轨 佛教仪制 书籍 中 611.2 BQN 47641 参访寺院50问 = 50 questions on visiting temples and monasteries 佛教仪制 书籍 中 法鼓文化 610 CFS 47643 素食50问 = 50 questions about being a vegetarian 佛教仪制 书籍 中 法鼓文化 619.1 SSW 47644 拜忏50问 = 50 questions on repentance prostration practice 佛教仪制 书籍 中 法鼓文化 615 BCW 47645 梵呗50问 = 50 questions on Buddhist chanting 佛教仪制 书籍 中 法鼓文化 615 FBW 47649 妙法莲华经的故事 佛教仪制 书籍 中 吴重德 和裕出版社 645.7 FXQ 47652 二六时中会瑜伽 要超度先人先超度自己 佛教仪制 书籍 中 永富 香海文化 615.3 YF 47654 生生自如 开启生命之奥秘 佛教仪制 书籍 中 依昱 香海文化 616.9 YY 47678 哭着过不如笑着活 佛教仪制 书籍 中 孙郡锴 中国华侨出版社 662.5 SJK 47700 观世音菩萨赞偈 憨山大师<<梦游集>> 佛教仪制 书籍 中 传印 庐山东林寺 645.34 CY 47602 名号如意宝 佛教宗派 书籍 中 益西彭措(智圆) 妙吉祥印经处 863.8 YXP 47603 净土之道 佛教宗派 书籍 中 益西彭措(智圆) 妙吉祥印经处 863.8 YXP 47604 大义人生 佛教宗派 书籍 中 益西彭措(智圆) 妙吉祥印经处 863.8 YXP 47605 净土真诠 佛教宗派 书籍 中 益西彭措(智圆) 妙吉祥印经处 863.8 YXP 47621 正见 = Almost Buddha 佛陀的证悟 佛教宗派 书籍 中 宗萨蒋扬钦哲( Dzongsar中国书籍出版社 Jamyang Khyentse) 849.1 DZO 47635 修心八颂讲记 = A teaching on the eight verses on mind training 佛教宗派 书籍 中 慈成加 释迦牟尼佛皈依中心 849.4 CCJ 47642 禅堂50问 = 50 questions about practicing Chan at a meditation hall 佛教宗派 书籍 中 法鼓文化 856 CTW 47656 直指明光心 《大手印指导教本 : 明现本来性》释论 佛教宗派 书籍 中 竹清嘉措( Tsultrim Gyamtso)众生文化出版 849.7 TSU 47663 悲智文集. -

Twenty Years of Taoist Practice 20Th Anniversary Commemorative Book of Taoist Federation (Singapore) 勤而行 二十载 新加坡道教总会成立二十周年纪念特刊

Twenty Years of Taoist Practice 20th Anniversary Commemorative Book of Taoist Federation (Singapore) 勤而行 二十载 新加坡道教总会成立二十周年纪念特刊 徐李颖⊙主编 Edited by Xu Liying 新加坡道教总会⊙出版 Published by Taoist Federation (Singapore) Twenty Years of Taoist Practice 20th Anniversary Commemorative Book of Taoist Federation (Singapore) 勤而行 二十载 新加坡道教总会成立二十周年纪念特刊 徐李颖⊙主编 Edited by Xu Liying 新加坡道教总会⊙出版 Published by Taoist Federation (Singapore) 书 名: 勤而行道二十载─ 新加坡道教总会二十周年纪念特刊 Book Title: Twenty Years of Taoist Practice 20th Anniversary Commemorative Book of Taoist Federation (Singapore) 顾 问: 陈添来BBM Advisor: Tan Thiam Lye BBM 主 编: 徐李颖 Edited by: Xu Liying 设 计: 陈立贤 Designed by: Tan Lee Sian 出 版: 新加坡道教总会 Published by: Taoist Federation (Singapore) 21, Bedok North Ave 4, Singapore 489948 Tel: (65) 6242 2115 Fax: (65) 6242 1127 设计承印: 高艺排版中心私营有限公司 Printed by: Superskill Graphics Pte Ltd Block 1001 Jalan Bukit Merah #03-11 Singapore 159455 Tel: (65) 6278 7888 Fax: (65) 6274 5565 出版日期: 2011年12月 Published in December 2011 ISBN 978-981-07-0218-2 版权所有,翻印必究 All rights reserved 目录 Contents 7 一、前言 24 新加坡道教总会第十届(2008/2010年度)理事会 Preface Taoist Federation (Singapore) 10th Management Committee (2008/2010) 9 二、新加坡道教总会 26 新加坡道教总会第十一届(2010/2012年度)理事会 历届理事会芳名录(1990-2012) Taoist Federation (Singapore)11th Management Committee Taoist Federation (Singapore) Management Committee (2010/2012) (1990 – 2012 ) 31 新加坡道教总会顾问团(2010/2012年度) 10 新加坡道教总会第一届(1990/1991年度)理事会 Taoist Federation (Singapore) Advisory Committee Taoist Federation (Singapore)1st Management Committee (2010/2012) (1990/1991) 32 新加坡道教总会第十一届(2010/2012年度)理事玉照 -

Everyday Life of Chinese Singaporeans: Past & Present

Module Code GES1005: Everyday Life of Chinese Singaporeans: Past & Present Tutorial Group D13 Assignment Name Temple Group Project - The Singapore Buddhist Lodge Date of Submission 31 October 2017 S/N Students’ Names 1. Chua Shu Zhen 2. Elsie Mok Kai Ying 3. Kong Kai Li TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: About the Temple 1 2.1 Background of Temple 1 2.1.1 Ties with Chinese Buddhist Circle 2 2.2 Main Gods & Secondary Gods 2 2.3 Temple Events 2 2.4 Preservations of Traditions 3 2.5 Interesting Stories 3 2.6 Temple Facilities and Features 4 Chapter 3: Reflections and Challenges 5 3.1 Reflections 5 3.2 Challenges 5 Chapter 4: References - Chapter 5: Appendices - APPENDICES Appendix A - Entrance of Singapore Buddhist Lodge Appendix B - Image of Sakyamuni Buddha Appendix C (1-10) - List of Secondary Gods Appendix D - Consecration Ceremony of Largest Amitabha Figure Appendix E - SBL Logo Appendix F - Red Cloth Strips Appendix G - Lotus Oil Lamp Appendix H - Article on the Complaints of SBL Appendix I - 1st Storey Layout: Courtyard Appendix J - 2nd Storey Layout: Office Appendix K - 3rd Storey Layout: Virtue Hall Appendix L - 4th Storey Layout: Library and Meeting Rooms Appendix M - 5th Storey Layout: Chanting Hall Appendix N - 6th Storey Layout: Storeroom Appendix O - 7th Storey Layout: Main Hall Appendix P - Donation Boxes Appendix Q - Screen Walls Appendix R - Symbolic Brazier Appendix S - Plaque Chapter 1: Introduction Temples are preserved as cultural artifacts which represent the history and rich cultures of ancient China. The temples are used as places of worship where devotees will visit to pay respect to the Gods and receive blessings. -

The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism (PDF)

The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism This book is published by Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive Bringing you the teachings of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche This book is made possible by kind supporters of the Archive who, like you, appreciate how we make these teachings freely available in so many ways, including in our website for instant reading, listening or downloading, and as printed and electronic books. Our website offers immediate access to thousands of pages of teachings and hundreds of audio recordings by some of the greatest lamas of our time. Our photo gallery and our ever-popular books are also freely accessible there. Please help us increase our efforts to spread the Dharma for the happiness and benefit of all beings. You can find out more about becoming a supporter of the Archive and see all we have to offer by visiting our website at http://www.LamaYeshe.com. Thank you so much, and please enjoy this ebook. Previously Published by the LAMA YESHE WISDOM ARCHIVE Becoming Your Own Therapist, by Lama Yeshe Advice for Monks and Nuns, by Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche Virtue and Reality, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Make Your Mind an Ocean, by Lama Yeshe Teachings from the Vajrasattva Retreat, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, by Lama Yeshe Daily Purification: A Short Vajrasattva Practice, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Making Life Meaningful, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Teachings from the Mani Retreat, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Direct and Unmistaken Method, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Yoga of Offering Food, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche -

Awaken to the Buddha Within Understanding and Practicing The

Ski ^Juliw Venerable Wuling is an American Buddhist nun of the Pure Land school of Mahayana Buddhism. More of her writingcan be found at wovw.amitabha-publications.org Amitabha Publications, Chicago, 60532 © 2006 by Amitabha Publications No part ofthis book may be altered without permission from the publisher. Reprinting is allowed fornon-profit use. For the latest edition, contact www.amitabha-publications.org Printed in Taiwan 15 14 13 12 89 10 11 12 ISBN: 978-1-59975-355-3 The Corporation Republic of Hwa Dzan Society 2F., No. 333-1, Sec. 4. Hsin Yi Road, Taipei, Taiwan Tel: (886)-2-2754-7178 Fax: (886)-2-2754-7262 E-Mail: [email protected] Contents Acknowledgment vii Buddhism Today 1 He Who Has Accomplished His Goal 8 The Great Awakening 18 Turning the Dharma Wheel 28 The Path to Liberation 38 Karma and Rebirth 49 The Three Dharma Seals 60 The Four Immeasurable Minds 65 The Five Precepts 72 The Six Paramitas 80 Taking the Three Refuges 116 Pure Land Buddhism 121 Acknowledgements With deep appreciation, I thank all those who have contributed to this book: family, friends, fellow students, and teachers. Without their support and patience, this book could never have come into being. I thank my teacher, Master Chin Kung, who over the past decade has wisely taught me the principles that are woven throughout this book. I thank my fellow students and friends who have so kindly taken the time to serve as consultants and editors. Any errors that remain are my own. I am deeply grateful to my parents, Milton and Evelyn Bolender, who provided the opportunity for me to follow my path in this lifetime. -

New Publications by ISEAS, 2009–10 83

Front Cover: A young girl faces a devastated landscape — the prospect of a regional scenario posed by global warming and environmental degradation. The photograph on the cover continues ISEAS’ practice of identifying an iconic image that embodies a regional challenge. This challenge is also reflected in the areas of research undertaken at ISEAS. (Photo Credit: nmedia, 2010 Used under license from Shutterstock.com) FrontCvr AR09-10.indd 2 6/18/10 7:23:36 PM A REGIONAL RESEARCH CENTRE DEDICATED TO THE STUDY OF SOCIO-POLITICAL, SECURITY, AND ECONOMIC TRENDS AND DEVELOPMENTS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND ITS WIDER GEOSTRATEGIC AND ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT Contents Executive Summary 4 Mission Statement 7 Organizational Structure 8 International Advisory Panel (IAP) 11 Research Programmes and Activities 12 Public Affairs Unit 39 Publications Unit 42 Library 44 Administration 52 Computer Unit 53 Appendices 55 I Research Staff 56 II Visiting Researchers and Affiliates 62 III Scholarship Award 72 IV Public Lectures, Conferences and Seminars 73 V New Publications by ISEAS, 2009–10 83 VI Donations, Grants, Contributions and Fees Received 86 Audited Financial Statements 89 Executive Summary n FY2009/10 the Institute of Southeast comprehensively at the religious, cultural I Asian Studies (ISEAS) witnessed a steady and economic interactions and diasporic consolidation of its two new centres, namely networks across Asia. Its first book was a the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC) and the volume of reflections on the Chola naval Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC). expeditions to Southeast Asia. The Centre also launched its research and working paper The ASC (launched on 21 July 2008), reflected series. -

Charisma in Buddhism?

CharismaCharisma inin BuddhismBuddhism By Ven. Piyasilo HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Charisma in Buddhism? sociological and doctrinal study of charisma, this book discusses three A past Buddhist workers — Father Sumaṅgalo, Ānanda Maṅgala Mahā. nāyaka Thera, Dr. Wong Phui Weng — and a living master, the charis matic Ajahn Yantra Amaro of Siam. Among other topics discussed are • Types of charisma • Genius, leadership and charisma • The Buddha as a charismatic leader • The Sangha and the routinization of charisma • Exploiting charisma • The disadvantages of charisma • Buddhist Suttas relating to charisma The Buddhist Currents series deals with topics of current interest relating to Buddhism in society today. Each title, a preprint from Buddhism, History and Society, gives a balanced treatment between academic views and Bud dhist doctrine to help understand the tension that exists today between religion (especially Buddhism) and society. Titles in the series (available where year is mentioned): • Buddhism, History and Society: Towards a postmodern perspective • Buddhist Currents: A brief social analysis of Buddhism in Sri Lanka and Siam (1992a) • Buddhism, Merit and Ideology • Charisma in Buddhism (1992h) Dharmafarer Enterprises P.O. Box 388, Jalan Sultan, 46740 Petaling Jaya, Malaysia ISBN 983 9030 10 8 Commemorating the Venerable Piyasīlo’s 20 Years of Monkhood A study of the work of Father Sumaṅgalo, Ānanda Maṅgala Mahā.nāyaka Thera and Dr. Wong Phui Weng in Malaysia and Singapore & Phra Ajahn Yantra Amaro [being a preprint of Buddhism, Society and History: towards a postmodern perspective] by Piyasīlo Dharmafarer Enterprises for The Community Of Dharmafarers 1992h [II:6.3–6.8] The Buddhist Currents Series This title forms part of the main work, Buddhism, History and Society (1992g) by Piyasīlo. -

A Plethora of Scenic Splendours" Gives an Account on What I Have Seen and Heard During My Stint

i. Table of Contents i. Table of Contents................................................................. 2 ii. Copyright & Terms of Use................................................... 5 iii. About Living Buddha Lian-sheng....................................... 6 iv. Preface.................................................................................. 8 1. Sanskrit Words And Moon Disc Appearing On Top Of The Head ..................................................................................... 11 2. Walking On A Glass Bridge ................................................ 14 3. Using Deva-eyes To Observe "Karma" ............................... 17 4. A Story Of A Woman Who Cannot Conceive ..................... 20 5. Headline In The Lian-he Evening News.............................. 23 6. The Experience Of Taking A Trishaw Ride ........................ 28 7. Kusu Island .......................................................................... 31 8. The Correct Knowledge And Correct View Of Li Mu Yuan .............................................................................................. 34 9. Lian Hua Jia Xing Told His Personal Experience................ 39 10. Killing And Committing Arson ........................................... 45 11. The Inner Meanings Of "Pu Men " Chapter......................... 48 12. True Buddha Empowerment ................................................ 51 13. Geomancy ............................................................................ 54 14. A Criticism Of An Analogy By Xing Yun,