The Coming of the Railways to Northampton, Northamptonshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia

Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Contents Foreword 3 Looking Ahead 5 Priorities in Detail • Great Eastern Main Line 6 • West Anglia Main Line 6 • Great Northern Route 7 • Essex Thameside 8 • Branch Lines 8 • Freight 9 A five county alliance • Norfolk 10 • Suffolk 11 • Essex 11 • Cambridgeshire 12 • Hertfordshire 13 • Connecting East Anglia 14 Our counties connected 15 Foreword Our vision is to release the industry, entrepreneurship and talent investment in rail connectivity and the introduction of the Essex of our region through a modern, customer-focused and efficient Thameside service has transformed ‘the misery line’ into the most railway system. reliable in the country, where passenger numbers have increased by 26% between 2005 and 2011. With focussed infrastructure We have the skills and enterprise to be an Eastern Economic and rolling stock investment to develop a high-quality service, Powerhouse. Our growing economy is built on the successes of East Anglia can deliver so much more. innovative and dynamic businesses, education institutions that are world-leading and internationally connected airports and We want to create a rail network that sets the standard for container ports. what others can achieve elsewhere. We want to attract new businesses, draw in millions of visitors and make the case for The railways are integral to our region’s economy - carrying more investment. To do this we need a modern, customer- almost 160 million passengers during 2012-2013, an increase focused and efficient railway system. This prospectus sets out of 4% on the previous year. -

The Carrying Trade and the First Railways in England, C1750-C1850

The Carrying Trade and the First Railways in England, c1750-c1850 Carolyn Dougherty PhD University of York Railway Studies November 2018 Abstract Transport and economic historians generally consider the change from moving goods principally on roads, inland waterways and coastal ships to moving them principally on railways as inevitable, unproblematic, and the result of technological improvements. While the benefits of rail travel were so clear that most other modes of passenger transport disappeared once rail service was introduced, railway goods transport did not offer as obvious an improvement over the existing goods transport network, known as the carrying trade. Initially most railways were open to the carrying trade, but by the 1840s railway companies began to provide goods carriage and exclude carriers from their lines. The resulting conflict over how, and by whom, goods would be transported on railways, known as the carrying question, lasted more than a decade, and railway companies did not come to dominate domestic goods carriage until the 1850s. In this study I develop a fuller picture of the carrying trade than currently exists, highlighting its multimodal collaborative structure and setting it within the ‘sociable economy’ of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century England. I contrast this economy with the business model of joint-stock companies, including railway companies, and investigate responses to the business practices of these companies. I analyse the debate over railway company goods carriage, and identify changes in goods transport resulting from its introduction. Finally, I describe the development and outcome of the carrying question, showing that railway companies faced resistance to their attempts to control goods carriage on rail lines not only from the carrying trade but also from customers of goods transport, the government and the general public. -

Download the Report Item 4

BOROUGH COUNCIL OF WELLINGBOROUGH AGENDA ITEM 4 Development Committee 17 February 2020 Report of the Principal Planning Manager Local listing of the Roundhouse and proposed Article 4 Direction 1 Purpose of report For the committee to consider and approve the designation of the Roundhouse (or number 2 engine shed) as a locally listed building and for the committee to also approve an application for the addition of an Article 4(1) direction to the building in order to remove permitted development rights and prevent unauthorised demolition. 2 Executive summary 2.1 The Roundhouse is a railway locomotive engine shed built in 1872 by the Midland Railway. There is some concern locally that the building could be demolished and should be protected. It was not considered by English Heritage to be worthy of national listing but it is considered by the council to be worthy of local listing. 2.2 Local listing does not protect the building from demolition but is a material consideration in a planning application. 2.3 An article 4(1) direction would be required to be in place to remove the permitted development rights of the owner. In this case it would require the owner to seek planning permission for the partial or total demolition of the building. 3 Appendices Appendix 1 – Site location plan Appendix 2 – Photos of site Appendix 3 – Historic mapping Appendix 4 – Historic England report for listing Appendix 5 – Local list criteria 4 Proposed action: 4.1 The committee is invited to APPROVE that the Roundhouse is locally listed and to APPROVE that an article 4 (1) direction can be made. -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

Introduction Railfuture Oxford to Cambridge (East West Rail)

9th September 2013 Railfuture Oxford to Cambridge (East West Rail) campaign Briefing note on route options for the Central Section from Bedford to Cambridge Introduction The government and the Office of Rail Regulation have approved the upgrading and rebuilding of the railway between Oxford and Bedford, the Western Section of East West Rail. Railfuture is a long-term campaigner for the completion of the East West Rail project to Cambridge and into East Anglia. The Eastern Section of the route is already in use from Norwich and Ely to Cambridge via the soon to be opened Cambridge Science Park station; from Ipswich via Bury St Edmunds and Newmarket to Cambridge; and from Stansted Airport to Cambridge. Map 1: The East West Rail Link Between Bedford and Cambridge some of the original route is lost to development and population growth in the region has occurred away from the original stations. The question of corridor and route selection is therefore a key factor in making the case for the Bedford to Cambridge (Central) section of East West Rail. Railfuture is assessing the candidate corridors that have been identified by the East West Rail (EWR) Consortium. An early conclusion is that routes for possible approaches to the two nodes, Bedford and Cambridge, should be agreed and protected at an early stage, such is the pace of growth and development. Page 1 of 10 9th September 2013 Purpose The purpose of this document is to set out the options for EWR route options for the approach to Cambridge from the west. The options for Bedford will be covered by another document. -

Catalog 210: Photographic Viewbooks

R & A PETRILLA, BOOKSELLERS P.O. Box 306 Roosevelt, NJ 08555 Catalog 210: Photographic Viewbooks 1. Alabama-Georgia-Carolinas-Florida. SINGER SOUVENIR OF THE SOUTH: Set of Ten Photographic Views. s.l.: Singer Sewing Machine Co., ca 1900. First Edition. Comprises 10 photographic views (11cm x 18cm) of Southern cities and scenes, each with a full-page Singer ad on the verso. Views include: Court Square, Montgomery, Ala.; Selling Cotton, Newman, Ga.; Scene on the French Broad River, NC; Pringle House, Charleston, SC; Silver Spring, Head of Ocklawaha River, Florida; &c. In the original illustrated envelope, edges split but intact. Views in fine condition. 4.75" x 7.5" Very Good. Portfolio. (#036829) $90.00 [Not recorded by WorldCat, which does find one holding of a set of 10 views of Boston, issued by Singer Co.] 2. Alaska, Yukon Territory. A HAND BOOK OF VACATION TRIPS IN ALASKA AND THE YUKON ON THE WHITE PASS AND YUKON ROUTE (via the Steamer "Whitehorse") . Seattle: Farwest, 1940. First Edition. 56pp; illustrated from photographs and strip maps. This guide offers various Yukon tours, including: The Trail of '98 to the Klondike Gold Fields; West Taku Arm; Whitehorse and the Yukon River; Miles Canyon and Whitehorse Rapids; The Yukon River to Dawson; Dawson to Whitehorse: &c. The description of each tour includes a brief history of places along the route, a strip map, and views from photographs (several full-page). The original owner made three neat, marginal notes regarding costs. Pictorial wrappers. 3.5" x 6" Fine. Pictorial Paper Covers. (#037142) $50.00 3. -

Train Times 12 December 2010 to 21 May 2011

Train Times 12 December 2010 to 21 May 2011 Great Northern Route London 6,500 Welwyn Garden City re Hertford North mo Stevenage seats! Peterborough See page 116 for details Cambridge King’s Lynn CI.GNA.1210 thameslinkprogramme.co.uk visit information, more – 16January 2011.For 20November Blackfriars willbeclosed from London (2230 –0430)andmostweekends. evenings Friday Herne to HillonMonday late Bridge / InternationalandLondon Pancras St / Town noservices are Kentish between There London Connections Maida Vale ST. PANCRAS St John’s KING’S RAIL SERVICES Warwick INTERNATIONAL Essex Road Zone MARYLEBONE Wood EUSTON CROSS Hoxton NATIONAL RAIL SERVICES Avenue Great Angel 2 First Capital Connect Royal Oak Portland Street Chiltern Railways Cambridge c2c Old Street Heath Baker King’s Cross FARRINGDON First Great Western Regents Euston Square Shoreditch Street St Pancras High Street London Midland Edgware Park Warren Street Barbican London Overground PADDINGTON Road Russell MOORGATE Bethnal Bayswater Goodge Square National Express Street Green East Anglia Holland Lancaster Bond LIVERPOOL Southern Notting Tottenham Park Gate Street Court Road Holborn STREET Southeastern Hill Gate Chancery Lane Zone South West Trains Shepherd’s Queensway Marble Oxford Heathrow Connect Bush Circus Arch Covent St Paul’s 1 Heathrow Express Zone 1 Garden Whitechapel Green Piccadilly Leicester Aldgate TfL SERVICES Kensington High Street Hyde Park Circus Bank Kensington Park Square City (thinner lines) Olympia Corner Thameslink FENCHURCH Aldgate Bakerloo Line East Knightsbridge Underground station STREET Central Line CHARING closed until late 2011 CANNON Circle Line South CROSS BLACKFRIARS Bank District Line Kensington Sloane STREET Shadwell Docklands Square Westminster Light Railway Mansion Monument Tower Tower Temple Hill Hammersmith & Earls Gloucester VICTORIA St. -

A Guide for Hirers of Milton Malsor Village Hall

WELCOME PACK A Guide for Hirers of Milton Malsor Village Hall Page 1 of 4 31/03/2013 Facilities & Utilities Entrance door, security and emergency Exit • A single door key operates all the locks fitted to the main entrance door & the door from the kitchen to the outside lobby. • Outside security lights are in operation in the car park and at the emergency exit door. • Power failure lights are in operation in the main hall, entrance hall and by the emergency exit door and ladies toilet area. Main hall (14.25m x 8.75m approx.) The maximum capacity allowed is 90 people. Sufficient chairs and tables for all to be seated are included in the hire charges. Features of the hall include: A large pull down projection screen. • A table store room to the left contains 20 x 1.52m x .76m tables and 3 smaller tables - if the tables are used please clean them before stacking away neatly. • Chair store room to the right. • On the near side is a hatchway & doorway leading to the kitchen. • Other doorways are for private use. The James meeting room (4.5m x 2.8m approx.) The room can accommodate 15 persons seated around 4 Tables. One wall is coated for use as a projection screen and a projector can be hired at extra cost; please advise the booking officer if you wish to hire the projector. Toilets o Gentlemen’s toilet on the left of the entrance hall. o Disabled toilets which contain a baby changing unit are also on the left of the entrance hall. -

Scottish Railways: Sources

Scottish Railways: Sources How to use this list of sources This is a list of some of the collections that may provide a useful starting point when researching this subject. It gives the collection reference and a brief description of the kinds of records held in the collections. More detailed lists are available in the searchroom and from our online catalogue. Enquiries should be directed to the Duty Archivist, see contact details at the end of this source list. Beardmore & Co (GUAS Ref: UGD 100) GUAS Ref: UGD 100/1/17/1-2 Locomotive: GA diesel electric locomotive GUAS Ref: UGD 100/1/17/3 Outline and weight diagram diesel electric locomotive Dunbar, A G; Railway Trade Union Collection (GUAS Ref: UGD 47) 1949-67 GUAS Ref: UGD 47/1/6 Dumbarton & Balloch Joint Railway 1897-1909 GUAS Ref: UGD 47/1/3 Dunbar, A G, Railway Trade Union Collection 1869-1890 GUAS Ref: UGD 47/3 Dunbar, A G, Railway Trade Union Collection 1891-1892 GUAS Ref: UGD 47/2 London & North Eastern Railway 1922-49 Mowat, James; Collection (GUAS Ref: UGD 137) GUAS Ref: UGD 137/4/3/2 London & North Western Railway not dated Neilson Reid & Co (GUAS Ref: UGD 10) 1890 North British Locomotive Co (GUAS Ref: UGD 11) GUAS Ref: UGD 11/22/41 Correspondence and costs for L100 contract 1963 Pickering, R Y & Co Ltd (GUAS Ref: UGD 12) not dated Scottish Railway Collection, The (GUAS Ref: UGD 8) Scottish Railways GUAS Ref: UGD 8/10 Airdrie, Coatbridge & Wishaw Junction Railway 1866-67 GUAS Ref: UGD 8/39 Airdrie, Coatbridge & Wishaw Junction Railway 1867 GUAS Ref: UGD 8/40 Airdrie, Coatbridge -

Download Alternative Route

ALTERNATIVE ROUTES DURING DISRUPTION KING’S LYNN Suggested alternative 37* Watlington Downham Market routes during times of Littleport ELY disruption XL* Waterbeach 9*,12* Cambridge North PETERBOROUGH CAMBRIDGE Journeys via alternative routes may take longer than B* Huntingdon your normal journey or operate only at certain times. Foxton St Neots Shepreth Meldreth Sandy On some alternative routes, you may need to purchase BEDFORD X5* Royston Biggleswade Ashwell & a ticket and apply for a refund*. Full details of where Flitwick Morden Arlesey Baldock your ticket will be accepted will be available on our Audley End websites during times of disruption. Harlington Letchworth Garden City HITCHIN 97, 98 Leagrave Stansted 55 Airport GreatNorthernRail.com STEVENAGE LUTON 101 Watton-at-Stone Bishops Stortford ThameslinkRailway.com LUTON AIRPORT 100 Knebworth Hertford PARKWAY 301 HERTFORD NORTH East Welwyn North 724 Harlow Town Hertford Further information will be available from the sources Harpenden 366, WELWYN GARDEN CITY 301 Bayford Bus Stn 610 724 Cuffley below: 242 Broxbourne ST ALBANS CITY 301, 302, 601 Hatfield 602, 653, 724 242 Crews Hill Cheshunt Welham Green National Rail Enquiries 610 601 Brookmans Park Gordon Hill Enfield Enfield nationalrail.co.uk Radlett Potters Bar Town 84 Chase 03457 48 49 50 313 High Hadley Wood Grange Park Elstree & Borehamwood Barnet New Barnet 107 Cockfosters Winchmore Hill Transport for London Oakleigh Park Tottenham (Tube & bus services within London travel zones) Mill Hill Broadway Palmers Green Hale New Southgate -

The Development of the Railway Network in Britain 1825-19111 Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Xuesheng You 1

The development of the railway network in Britain 1825-19111 Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Xuesheng You 1. Introduction This chapter describes the development of the British railway network during the nineteenth century and indicates some of its effects. It is intended to be a general introduction to the subject and takes advantage of new GIS (Geographical Information System) maps to chart the development of the railway network over time much more accurately and completely than has hitherto been possible. The GIS dataset stems from collaboration by researchers at the University of Cambridge and a Spanish team, led by Professor Jordi Marti-Henneberg, at the University of Lleida. Our GIS dataset derives ultimately from the late Michael Cobb’s definitive work ‘The Railways of Great Britain. A Historical Atlas’. Our account of the development of the British railway system makes no pretence at originality, but the chapter does present some new findings on the economic impact of the railways that results from a project at the University of Cambridge in collaboration with Professor Dan Bogart at the University of California at Irvine.2 Data on railway developments in Scotland are included but we do not discuss these in depth as they fell outside the geographical scope of the research project that underpins this chapter. Also, we focus on the period up to 1911, when the railway network grew close to its maximal extent, because this was the end date of our research project. The organisation of the chapter is as follows. The next section describes the key characteristics of the British transport system before the coming of the railways in the nineteenth century. -

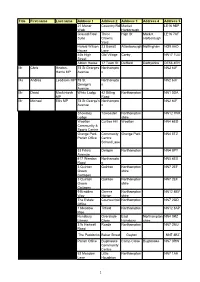

Title First Name Last Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4

Title First name Last name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 Address 5 21 Manor Coventry Rd Market LE16 9BP Walk Harborough Ground Floor Three High St Market LE16 7AF Suite Crowns Harborough Yard Harold Wilson 23 Barratt Attenborough Nottingham NG9 6AD House Lane 44b High Old Village Corby NN17 1UU Street Albion House 17 Town St Duffield Derbyshire DE56 4EH Mr Chris Heaton- 78 St Georges Northampto NN2 6JF Harris MP Avenue n Ms Andrea Leadsom MP 78 St. Northampto NN2 6JF George's n Avenue Mr David Mackintosh White Lodge 42 Billing Northampton NN1 5DA MP Road Mr Michael Ellis MP 78 St George's Northampto NN2 6JF Avenue n Showsley Towcester Northampton NN12 7NR Lodge shire Wootton Curtlee Hill Wootton NN4 6ED Community & Sports Centre Grange Park Community Grange Park NN4 5TZ Parish Office Centre School Lane 33 Friars Delapre Northampton NN4 8PY Avemue 417 Weedon Northampto NN5 4EX Road n 3 Quinton Quinton Northampton NN7 2EF Green shire Cottages 3 Quinton Quinton Northampton NN7 2EF Green shire Cottages 9 Bradden Greens Northampton NN12 8BY Way Norton shire The Estate Courteenhal Northampton NN7 2QD Office l 1 Meadow Tiffield Northampton NN12 8AP Rise Hunsbury Overslade East Northampton NN4 0RZ Library Close Hunsbury shire 31b Hartwell Roade Northampton NN7 2NU Road The Paddocks Baker Street Gayton NN7 3EZ Parish Office Bugbrooke Camp Close Bugbrooke NN7 3RW Community Centre 52 Meadow Little Northampton NN7 1AH Lane Houghton 1 Title First name Last name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 Address 5 Greenglades West Northampton