Ecclesiastes: the Philippians of the Old Testament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Reexamination of "Eternity" in Ecclesiastes 3:11

BiBLiOTHECA SACRA 165 (January-March 2008): 39-57 A REEXAMINATION OF "ETERNITY" IN ECCLESIASTES 3:11 Brian P. Gault HE PHRASE "GOD HAS PLACED ETERNITY IN THE HUMAN HEART" (Eccles. 3I11)1 has become cliché in contemporary missiology Tand a repeated refrain from many Christian pulpits today. In his popular work, Eternity in Their Hearts, missiologist Don Richardson reports on stories that reveal a belief in the one true God in many cultures around the world. Based on Qoheleth's words Richardson proposes that God has prepared the world for the gos pel of Jesus Christ.2 In support of his thesis Richardson appeals to the words of the late scholar Gleason Archer, "Humankind has a God-given ability to grasp the concept of eternity."3 While com monly accepted by scholars and laypersons alike, this notion is cu riously absent from the writings of the early church fathers4 as well as the major theological treatise of William Carey, the founder of the modern missionary movement.5 In fact modern scholars have suggested almost a dozen different interpretations for this verse. In Brian P. Gault is a Ph.D. student in Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East at Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, Ohio. 1 Unless noted otherwise, all Scripture quotations are those of the present writer. 2 Don Richardson, Eternity in Their Hearts (Ventura, CA: Regal, 1981), 28. 3 Personal interview cited by Don Richardson, "Redemptive Analogy," in Perspec tives on the World Christian Movement, ed. Ralph D. Winter and Steven C. Hawthorne (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2000), 400. -

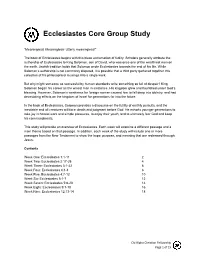

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless!” The book of Ecclesiastes begins with this bleak exclamation of futility. Scholars generally attribute the authorship of Ecclesiastes to King Solomon, son of David, who was once one of the wealthiest men on the earth. Jewish tradition holds that Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes towards the end of his life. While Solomon’s authorship is not commonly disputed, it is possible that a third party gathered together this collection of his philosophical musings into a single work. But why might someone so successful by human standards write something so full of despair? King Solomon began his career as the wisest man in existence. His kingdom grew and flourished under God’s blessing. However, Solomon’s weakness for foreign women caused him to fall deep into idolatry, and had devastating effects on the kingdom of Israel for generations far into the future. In the book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon provides a discourse on the futility of earthly pursuits, and the inevitable end all creatures will face: death and judgment before God. He exhorts younger generations to take joy in honest work and simple pleasures, to enjoy their youth, and to ultimately fear God and keep his commandments. This study will provide an overview of Ecclesiastes. Each week will examine a different passage and a main theme based on that passage. In addition, each week of the study will include one or more passages from the New Testament to show the hope, purpose, and meaning that are redeemed through Jesus. Contents Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 2 Week Two: Ecclesiastes 2:17-26 4 Week Three: Ecclesiastes 3:1-22 6 Week Four: Ecclesiastes 4:1-3 8 Week Five: Ecclesiastes 4:7-12 10 Week Six: Ecclesiastes 5:1-7 12 Week Seven: Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 14 Week Eight: Ecclesiastes 9:1-10 16 Week Nine: Ecclesiastes 12:13-14 18 Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship Page 1 of 19 Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 Worship Idea: Open in prayer, then sing some worship songs Opening Questions: 1. -

Ecclesiastes – “It’S ______About _____”

“DISCOVERING THE UNREAD BESTSELLER” Week 18: Sunday, March 25, 2012 ECCLESIASTES – “IT’S ______ ABOUT _____” BACKGROUND & TITLE The Hebrew title, “___________” is a rare word found only in the Book of Ecclesiastes. It comes from a word meaning - “____________”; in fact, it’s talking about a “_________” or “_________”. The Septuagint used the Greek word “__________” as its title for the Book. Derived from the word “ekklesia” (meaning “assembly, congregation or church”) the title again (in the Greek) can simply be taken to mean - “_________/_________”. AUTHORSHIP It is commonly believed and accepted that _________authored this Book. Within the Book, the author refers to himself as “the son of ______” (Ecclesiastes 1:1) and then later on (in Ecclesiastes 1:12) as “____ over _____ in Jerusalem”. Solomon’s extensive wisdom; his accomplishments, and his immense wealth (all of which were God-given) give further credence to his work. Outside the Book, _______ tradition also points to Solomon as author, but it also suggests that the text may have undergone some later editing by _______ or possibly ____. SNAPSHOT OF THE BOOK The Book of Ecclesiastes describes Solomon’s ______ for meaning, purpose and satisfaction in life. The Book divides into three different sections - (1) the _____ that _______ is ___________ - (Ecclesiastes 1:1-11); (2) the ______ that everything is meaningless (Ecclesiastes 1:12-6:12); and, (3) the ______ or direction on how we should be living in a world filled with ______ pursuits and meaninglessness (Ecclesiastes 7:1-12:14). That last section is important because the Preacher/Teacher ultimately sees the emptiness and futility of all the stuff people typically strive for _____ from God – p______ – p_______ – p________ - and p________. -

Final Draft Dissertation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Arbiters of the Afterlife: Olam Haba, Torah and Rabbinic Authority A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures by Candice Liliane Levy 2013 © Copyright by Candice Liliane Levy 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Arbiters of the Afterlife: Olam Haba, Torah and Rabbinic Authority by Candice Liliane Levy Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Carol Bakhos, Chair As the primary stratum of the rabbinic corpus, the Mishna establishes a dynamic between rabbinic authority and olam haba that sets the course for all subsequent rabbinic discussions of the idea. The Mishna Sanhedrin presents the rabbis as arbiters of the afterlife, who regulate its access by excluding a set of individuals whose beliefs or practices undermine the nature of rabbinic authority and their tradition. In doing so, the Mishna evinces the foundational tenets of rabbinic Judaism and delineates the boundaries of ‘Israel’ according to the rabbis. Consequently, as arbiters of the afterlife, the rabbis constitute Israel and establish normative thought and practice in this world by means of the world to come. ii There have been surprisingly few studies on the afterlife in rabbinic literature. Many of the scholars who have undertaken to explore the afterlife in Judaism have themselves remarked upon the dearth of attention this subject has received. For the most part, scholars have sought to identify what the rabbis believed with regard to the afterlife and how they envisioned its experience, rather than why they held such beliefs or how the afterlife functioned within the rabbinic tradition. -

A Time to Let Go

A Time to Let Go Summary and Goal As Ecclesiastes reminds us, there is a time for everything in our lives. Winter is an important season and does some important work. In every life, there comes a time to let go and move on to our future. Main Passages Ecclesiastes 3:1-11 Session Outline 1. The Sovereignty of God from Beginning to End (Ecclesiastes 3:1-2) 2. Seasons of Peace and Strife (Ecclesiastes 3:3-8) 3. The Frustration of the Immediate in Light of Eternity (Ecclesiastes 3:9-11) Theological Theme God is sovereign throughout every season of life. Christ Connection In His earthly ministry, Jesus experienced every season of life—even leading to His own crucifixion. God’s power and sovereignty was shown as every detail of Jesus’ life fulfilled His promise in redemptive history. Missional Application One of the difficult questions frequently posed to believers has to do with God’s power in bleak seasons of suffering and loss. In understanding that God’s sovereignty never waivers, even in seasons of loss, believers can walk through those times with hope. 1 Leader Guide Historical Context of Ecclesiastes Purpose Ecclesiastes shows us that since we and our works are futile—that is, destined to perish—we must not waste our lives trying to justify our existence with pursuits that ultimately mean nothing. Put simply, Ecclesiastes examines major endeavors of life in light of the reality of death. Author According to 1:1 and 1:12, the author was David’s son and a king over Israel from Jerusalem. -

In Search of Kohelet

IN SEARCH OF KOHELET By Christopher P. Benton Ecclesiastes is simultaneously one of the most popular and one of the most misunderstood books of the Bible. Too often one hears its key verse, “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity,” interpreted as simply an injunction against being a vain person. The common English translation of this verse (Ecclesiastes 1:2) comes directly from the Latin Vulgate, “Vanitas vanitatum, ominia vanitas.” However, the original Hebrew, “Havel havelim, hachol havel,” may be better translated as “Futility of futilities, all is futile.” Consequently, Ecclesiastes 1:2 is more a broad statement about the meaninglessness of life and actions that are in vain rather than personal vanity. In addition to the confusion that often surrounds the English translation of Ecclesiastes 1:2, the appellation for the protagonist in Ecclesiastes also loses much in the translation. In the enduring King James translation of the Bible, the speaker in Ecclesiastes is referred to as “the Preacher,” and in many other standard English translations of the Bible (Amplified Bible, New International Version, New Living Translation, American Standard Version) one finds the speaker referred to as either “the Preacher” or “the Teacher.” However, in the original Hebrew and in many translations by Jewish groups, the narrator is referred to simply as Kohelet. The word Kohelet is derived from the Hebrew root koof-hey-lamed meaning “to assemble,” and commentators suggest that this refers to either the act of assembling wisdom or to the act of meeting with an assembly in order to teach. Furthermore, in the Hebrew, Kohelet is generally used as a name, but in Ecclesiastes 12:8 it is also written as HaKohelet (the Kohelet) which is more suggestive of a title. -

Ecclesiastes 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Ecclesiastes 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew text is all of verse 1. The Septuagint translation (third century B.C.) gave it the name "Ekklesiastes," from which the English title is a transliteration. This Greek word is related to ekklesia, meaning "assembly." "Ekklesiastes" is the Greek translation of the Hebrew word qohelet that the NASB translated "Preacher" in verse 1. The Hebrew word designates a leader who speaks before an assembly of people. As such, this book is a sermon.1 The NIV translation of qohelet as "Teacher" is also a good one. A more literal translation of qohelet would be "Gatherer," as the gatherer of people to an assembly, or the gatherer of thoughts or observations. WRITER AND DATE "… there is scarcely one aspect of the book, whether of date, authorship or interpretation, that has not been the subject of wide difference of opinion."2 The commentators sometimes treat the Hebrew word qohelet ("Preacher"; 1:1-2, 12; 7:27; 12:8-10) as a proper name.3 However, the fact that the article is present on the Hebrew word in 12:8, and perhaps in 7:27, seems to indicate that qohelet is a title: "the preacher" or "the teacher" or "the assembler" or "the convener." 1J. Sidlow Baxter, Explore the Book, 3:143. 2Robert Gordis, Koheleth—The Man and His World, p. 4. 3E.g., ibid., p. 5. Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. Constable www.soniclight.com 2 Dr. Constable's Notes on Ecclesiastes 2021 Edition Internal references point to Solomon as this preacher (cf. -

Funeral Readings

P a g e | 1 Readings for Catholic Funerals Old Testament / Hebrew Scripture 2 Maccabees 12:43-45 ................................................................................................................... 2 Job 19:1, 23-27A ............................................................................................................................ 3 Ecclesiastes 3: 1-8 .......................................................................................................................... 4 Ecclesiastes 3: 1-15 ........................................................................................................................ 5 Wisdom 3:1-9 ................................................................................................................................ 6 Wisdom 4:7-15 .............................................................................................................................. 7 Isaiah 25:6a, 7-9 ............................................................................................................................. 8 Lamentations 3:17-26 ................................................................................................................... 9 Daniel 12: 1-3............................................................................................................................... 10 New Testament / Christian Scripture Acts of the Apostles 10: 34-43 ................................................................................................... 11 Romans 5:5-11 ............................................................................................................................ -

Don't Freak Out, but YOU Are Not in Control Ecclesiastes 3:1-4:3 What's

Don’t freak out, but YOU are not in control Ecclesiastes 3:1-4:3 What’s the Point!?! Sermon 05 Out of the night that covers me, Black as the Pit from pole to pole, I thank whatever gods may be For my unconquerable soul. In the fell clutch of circumstance I have not winced nor cried aloud. Under the bludgeonings of chance My head is bloody, but unbowed. Beyond this place of wrath and tears Looms but the Horror of the shade, And yet the menace of the years Finds, and shall find, me unafraid. It matters not how strait the gate, How charged with punishments the scroll. I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul. That short Victorian poem, Invictus, was written by English poet, William Ernest Henley in 1875. When he was 14, Henley contracted a bone disease. A few years later, the disease had progressed to his foot. His doctor told him that the only way they could save his life was to amputate his leg just below the knee. So at 17 years of age, he half of his leg was amputated. While recovering from surgery, he wrote Invictus. “I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.” But he wasn’t, though he apparently had a full life, at age 53, William Ernest Henley died. Are you a control freak? Do you like to be in control? We humans love to be in control, to be the “masters of our fate: captains of our souls.” Ladies, does it drive you nuts when someone else works in your kitchen and moves things around? Are you that way at work? You have things just so in your workspace. -

Ecclesiastes 3

Ecclesiastes 3 Ecclesiastes chapters 3 (ESV) Keep the poem in verses 3:1-8 in context with the rest of the following verses 3:9-15. In 3:9 of this chapter the opening theme found in Ecclesiastes 1:3 – “What does man gain by all the toil at which he toils under the sun?” (Which in chapter one is followed by an expression of the temporal, meaninglessness of the cycles of nature, man and life.) 3:1 – “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven:” A. Topic is: The Proper Time B. Proverbs 15;23 – “To make an apt answer is a joy to a man, and a word in season, how good it is!” C. Proverbs 26:4 do not answer a fool is contrasted with Proverbs 26:5 to answer the fool. The key to this wisdom is knowing the right time. D. There is no real difference between the words “season” and “time”. Both words indicate specific points in time. E. “Time” appears 28 times in seven verses. F. “Event” or “every matter” refers to human activity that results as a choice made by man. G. The student of these verses has to decide which is the focus: a. Is Qohelet saying that the extreme of every action and decision a man makes is appropriate, and even necessary, at the right time. b. OR, is Qohelet saying that all events are in the hands of God either causes or judges with approval every action in its appropriate time. H. It is possible that Qohelt is saying that although there is a right time for all these things, the challenge comes in knowing WHEN that time is. -

The LXX Myth and the Rise of Textual Fixity*

Journal for the Study of Judaism Journal for the Study of Judaism 43 (2012) 1-21 brill.nl/jsj The LXX Myth and the Rise of Textual Fixity* Francis Borchardt Lutheran Theological Seminary (Hong Kong) 50 To Fung Shan Road, Shatin, Hong Kong [email protected] Abstract This brief study investigates the desire for a fixed textual form as it pertains to scripture in the Judean tradition. It particularly delves into this phenomenon in three early versions of the Septuagint origin myth. This paper argues that this myth is invaluable for the study of transmission and reception of scripture, as it is one of the earliest testimonies to the desire for a scriptural text to be frozen. By highlighting the ways the author of the Letter of Aristeas, Philo, and Josephus deal with the issue of textual fixity in the origin myth, this study aims to elucidate the range of opinions held by Judeans concerning the process of transmission of their holy books. Keywords Aristeas, Philo, Josephus, Septuagint The myth1 of the origin of the LXX, known to us in various forms, is often investigated for its potential to shed light on the translation process,2 the *) This study was prepared under the auspices of the EURYI project “The Birth and Trans- mission of Holy Tradition led by Juha Pakkala at the University of Helsinki. The group has provided funding and a setting for enlightening discussion. 1) The use of the term myth here should not be understood as derogatory or as a judgment about the objective truth or accuracy behind a story or belief. -

1 Transcription of 20ID4034 Ecclesiastes 3:12-22 "Solomon's

Transcription of 20ID4034 Ecclesiastes 3:12-22 "Solomon's Conflicted Views" June 7, 2020 All right. Let's open our Bibles to Ecclesiastes Chapter 3 verse 12 this morning, as we continue our kind of trip through Solomon's journal. Solomon, David's son, was a godly young boy. In fact, when he was old enough to take over for his dad, his first and only request from the Lord was wisdom to rule as well as his dad had; and at least early on, that was exactly what he did. God was very pleased that he hadn't asked for money or long life or power; that he just asked for wisdom, and so the Lord gave him all that. In fact, he became the wisest man that ever lived, to this day. No one after him, no one before him was wiser, and he used that wisdom to serve the Lord. It went well. The nation did well. It was at its zenith, and for many years he seemed to be just on the path of serving God. And then he began to marry a lot of very strange heathen women, much of them through political alliances. It was a common practice of the day. Shouldn't have been for him. But in his later years, these wives turned his heart away from the God that he knew and had grown up with. And so Solomon spent several years of his life wealthy, powerful, able to chase down life under the world to see if there was a life apart from God to be found in the world.