The LXX Myth and the Rise of Textual Fixity*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Reexamination of "Eternity" in Ecclesiastes 3:11

BiBLiOTHECA SACRA 165 (January-March 2008): 39-57 A REEXAMINATION OF "ETERNITY" IN ECCLESIASTES 3:11 Brian P. Gault HE PHRASE "GOD HAS PLACED ETERNITY IN THE HUMAN HEART" (Eccles. 3I11)1 has become cliché in contemporary missiology Tand a repeated refrain from many Christian pulpits today. In his popular work, Eternity in Their Hearts, missiologist Don Richardson reports on stories that reveal a belief in the one true God in many cultures around the world. Based on Qoheleth's words Richardson proposes that God has prepared the world for the gos pel of Jesus Christ.2 In support of his thesis Richardson appeals to the words of the late scholar Gleason Archer, "Humankind has a God-given ability to grasp the concept of eternity."3 While com monly accepted by scholars and laypersons alike, this notion is cu riously absent from the writings of the early church fathers4 as well as the major theological treatise of William Carey, the founder of the modern missionary movement.5 In fact modern scholars have suggested almost a dozen different interpretations for this verse. In Brian P. Gault is a Ph.D. student in Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East at Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, Ohio. 1 Unless noted otherwise, all Scripture quotations are those of the present writer. 2 Don Richardson, Eternity in Their Hearts (Ventura, CA: Regal, 1981), 28. 3 Personal interview cited by Don Richardson, "Redemptive Analogy," in Perspec tives on the World Christian Movement, ed. Ralph D. Winter and Steven C. Hawthorne (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2000), 400. -

Wisdom in Daniel and the Origin of Apocalyptic

WISDOM IN DANIEL AND THE ORIGIN OF APOCALYPTIC by GERALD H. WILSON University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 In this paper, I am concerned with the relationship of the book of Daniel and the biblical wisdom literature. The study draws its impetus from the belief of von Rad that apocalyptic is the "child" of wisdom (1965, II, pp. 304-15). My intent is to test von Rad's claim by a study of wisdom terminology in Daniel in order to determine whether, in fact, that book has its roots in the wisdom tradition. Adequate evidence has been gathered to demonstrate a robust connection between the nar ratives of Daniel 1-6 and mantic wisdom which employs the interpreta tion of dreams, signs and visions (Millier, 1972; Collins, 1975). Here I am concerned to dispell the continuing notion that apocalyptic as ex hibited in Daniel (especially in chapters 7-12) is the product of the same wisdom circles from which came the proverbial biblical books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Job and the later Ben Sirach. 1 I am indebted to the work of Why bray ( 1974), who has dealt exhaustively with the terminology of biblical wisdom, and to the work of Crenshaw (1969), who, among others, has rightly cautioned that the presence of wisdom vocabulary is insufficient evidence of sapiential influence. 2 Whybray (1974, pp. 71-154) distinguishes four categories of wisdom terminology: a) words from the root J:ikm itself; b) other characteristic terms occurring only in the wisdom corpus (5 words); c) words char acteristic of wisdom, but occurring so frequently in other contexts as to render their usefulness in determining sapiential influence questionable (23 words); and d) words characteristic of wisdom, but occurring only occasionally in other OT traditions (10 words). -

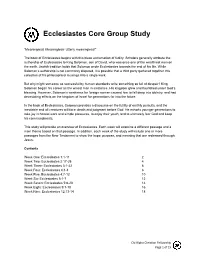

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless!” The book of Ecclesiastes begins with this bleak exclamation of futility. Scholars generally attribute the authorship of Ecclesiastes to King Solomon, son of David, who was once one of the wealthiest men on the earth. Jewish tradition holds that Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes towards the end of his life. While Solomon’s authorship is not commonly disputed, it is possible that a third party gathered together this collection of his philosophical musings into a single work. But why might someone so successful by human standards write something so full of despair? King Solomon began his career as the wisest man in existence. His kingdom grew and flourished under God’s blessing. However, Solomon’s weakness for foreign women caused him to fall deep into idolatry, and had devastating effects on the kingdom of Israel for generations far into the future. In the book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon provides a discourse on the futility of earthly pursuits, and the inevitable end all creatures will face: death and judgment before God. He exhorts younger generations to take joy in honest work and simple pleasures, to enjoy their youth, and to ultimately fear God and keep his commandments. This study will provide an overview of Ecclesiastes. Each week will examine a different passage and a main theme based on that passage. In addition, each week of the study will include one or more passages from the New Testament to show the hope, purpose, and meaning that are redeemed through Jesus. Contents Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 2 Week Two: Ecclesiastes 2:17-26 4 Week Three: Ecclesiastes 3:1-22 6 Week Four: Ecclesiastes 4:1-3 8 Week Five: Ecclesiastes 4:7-12 10 Week Six: Ecclesiastes 5:1-7 12 Week Seven: Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 14 Week Eight: Ecclesiastes 9:1-10 16 Week Nine: Ecclesiastes 12:13-14 18 Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship Page 1 of 19 Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 Worship Idea: Open in prayer, then sing some worship songs Opening Questions: 1. -

The King Who Will Rule the World the Writings (Ketuvim) Mako A

David’s Heir – The King Who Will Rule the World The Writings (Ketuvim) Mako A. Nagasawa Last modified: September 24, 2009 Introduction: The Hero Among ‘the gifts of the Jews’ given to the rest of the world is a hope: A hope for a King who will rule the world with justice, mercy, and peace. Stories and legends from long ago seem to suggest that we are waiting for a special hero. However, it is the larger Jewish story that gives very specific meaning and shape to that hope. The theme of the Writings is the Heir of David, the King who will rule the world. This section of Scripture is very significant, especially taken all together as a whole. For example, not only is the Book of Psalms a personal favorite of many people for its emotional expression, it is a prophetic favorite of the New Testament. The Psalms, written long before Jesus, point to a King. The NT quotes Psalms 2, 16, and 110 (Psalm 110 is the most quoted chapter of the OT by the NT, more frequently cited than Isaiah 53) in very important places to assert that Jesus is the King of Israel and King of the world. The Book of Chronicles – the last book of the Writings – points to a King. He will come from the line of David, and he will rule the world. Who will that King be? What will his life be like? Will he usher in the life promised by God to Israel and the world? If so, how? And, what will he accomplish? How worldwide will his reign be? How will he defeat evil on God’s behalf? Those are the major questions and themes found in the Writings. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

Ecclesiastes – “It’S ______About _____”

“DISCOVERING THE UNREAD BESTSELLER” Week 18: Sunday, March 25, 2012 ECCLESIASTES – “IT’S ______ ABOUT _____” BACKGROUND & TITLE The Hebrew title, “___________” is a rare word found only in the Book of Ecclesiastes. It comes from a word meaning - “____________”; in fact, it’s talking about a “_________” or “_________”. The Septuagint used the Greek word “__________” as its title for the Book. Derived from the word “ekklesia” (meaning “assembly, congregation or church”) the title again (in the Greek) can simply be taken to mean - “_________/_________”. AUTHORSHIP It is commonly believed and accepted that _________authored this Book. Within the Book, the author refers to himself as “the son of ______” (Ecclesiastes 1:1) and then later on (in Ecclesiastes 1:12) as “____ over _____ in Jerusalem”. Solomon’s extensive wisdom; his accomplishments, and his immense wealth (all of which were God-given) give further credence to his work. Outside the Book, _______ tradition also points to Solomon as author, but it also suggests that the text may have undergone some later editing by _______ or possibly ____. SNAPSHOT OF THE BOOK The Book of Ecclesiastes describes Solomon’s ______ for meaning, purpose and satisfaction in life. The Book divides into three different sections - (1) the _____ that _______ is ___________ - (Ecclesiastes 1:1-11); (2) the ______ that everything is meaningless (Ecclesiastes 1:12-6:12); and, (3) the ______ or direction on how we should be living in a world filled with ______ pursuits and meaninglessness (Ecclesiastes 7:1-12:14). That last section is important because the Preacher/Teacher ultimately sees the emptiness and futility of all the stuff people typically strive for _____ from God – p______ – p_______ – p________ - and p________. -

Proverbs Part One: Ten Instructions for the Wisdom Seeker

PROVERBS 67 Part One: Ten Instructions for the Wisdom Seeker Chapters 1-9 Introduction.Proverbs is generally regarded as the COMMENTARY book that best characterizes the Wisdom tradition. It is presented as a “guide for successful living.” Its PART 1: Ten wisdom instructions (Chapters 1-9) primary purpose is to teach wisdom. In chapters 1-9, we find a set of ten instructions, A “proverb” is a short saying that summarizes some aimed at persuading young minds about the power of truths about life. Knowing and practicing such truths wisdom. constitutes wisdom—the ability to navigate human relationships and realities. CHAPTER 1: Avoid the path of the wicked; Lady Wisdom speaks The Book of Proverbs takes its name from its first verse: “The proverbs of Solomon, the son of David.” “That men may appreciate wisdom and discipline, Solomon is not the author of this book which is a may understand words of intelligence; may receive compilation of smaller collections of sayings training in wise conduct….” (vv 2-3) gathered up over many centuries and finally edited around 500 B.C. “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge….” (v.7) In Proverbs we will find that certain themes or topics are dealt with several times, such as respect for Verses 1-7.In these verses, the sage or teacher sets parents and teachers, control of one’s tongue, down his goal: to instruct people in the ways of cautious trust of others, care in the selection of wisdom. friends, avoidance of fools and women with loose morals, practice of virtues such as humility, The ten instructions in chapters 1-9 are for those prudence, justice, temperance and obedience. -

Final Draft Dissertation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Arbiters of the Afterlife: Olam Haba, Torah and Rabbinic Authority A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures by Candice Liliane Levy 2013 © Copyright by Candice Liliane Levy 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Arbiters of the Afterlife: Olam Haba, Torah and Rabbinic Authority by Candice Liliane Levy Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Carol Bakhos, Chair As the primary stratum of the rabbinic corpus, the Mishna establishes a dynamic between rabbinic authority and olam haba that sets the course for all subsequent rabbinic discussions of the idea. The Mishna Sanhedrin presents the rabbis as arbiters of the afterlife, who regulate its access by excluding a set of individuals whose beliefs or practices undermine the nature of rabbinic authority and their tradition. In doing so, the Mishna evinces the foundational tenets of rabbinic Judaism and delineates the boundaries of ‘Israel’ according to the rabbis. Consequently, as arbiters of the afterlife, the rabbis constitute Israel and establish normative thought and practice in this world by means of the world to come. ii There have been surprisingly few studies on the afterlife in rabbinic literature. Many of the scholars who have undertaken to explore the afterlife in Judaism have themselves remarked upon the dearth of attention this subject has received. For the most part, scholars have sought to identify what the rabbis believed with regard to the afterlife and how they envisioned its experience, rather than why they held such beliefs or how the afterlife functioned within the rabbinic tradition. -

The Book of Proverbs: Wisdom for Life August 5Th, 2015 Text

The Book of Proverbs: Wisdom for Life August 5th, 2015 Text: Proverbs 1:1-7 Background/Theme: The book of Proverbs was written mainly by Solomon (known as Israel’s wisest king) yet some of the later sections were written by men named Lemuel and Agur (See Prov. 1:1). It was written during Solomon’s reign (970-930 B.C.). Solomon asked God for wisdom to rule God’s nation and God granted it (1 Kings 3:6-14). Proverbs along with Job, Psalms, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon are known as the writings or “Wisdom Books” addressing practical living before God. The theme of Proverbs is wisdom (the skilled and right use of knowledge). The main purpose of this book is to teach wisdom to God’s people through the use of proverbs. The word Proverb means “to be like.” Therefore, Proverbs are short statements, which compare and contrast common, concrete images with life’s most profound truth. They are practical and point the way to godly character. These proverbs address subjects such as: life, family, friends, good judgment, and distinctions between the wise and foolish man. Proverbs is not a do-it-yourself success kit for the greedy but a guidebook for the godly. This starts with fearing the LORD. Memory Verse: Prov. 1:7 Outline: Ch 1-9-Solomon writes wisdom for younger people. Ch 10-24 - There is wisdom on various topics that apply to the average person. Ch 25-31 - Wisdom for leaders is provided. Tips for reading proverbs-Proverbs are statements of general truth and must not be taken as divine promises (Prov. -

Social Identity in the Letter of Aristeas Noah Hacham (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) and Lilach Sagiv (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem)*

Social Identity in the Letter of Aristeas Noah Hacham (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) and Lilach Sagiv (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem)* The Letter of Aristeas has long been considered the work most emblematic, elucidatory and de- clarative of Jewish identity in Hellenistic Egypt. The work embraces emphatically Jewish content alongside a profound identification with Hellenistic concepts, ideas and frameworks. This com- plexity has intrigued scholars and it continues to do so as they attempt to qualify the essential identity that the author of the Letter of Aristeas seeks to promote and to transmit. The question of identity is two-faceted: First, it explores the nature of the affinity between the Jewish and Hellenistic components in the doctrine advocated by the Letter of Aristeas. Second, it strives to identify the threat and the danger that the author confronts and deplores. In our discussion we aim to provide answers to these questions. Furthermore, we introduce a new conceptualiza- tion of the way the Letter of Aristeas combines and “manages” the various identities and their constituent details. For that aim, we draw on models from the realm of social psychology, which we have found to be eminently useful in understanding the complex and dynamic nature of the identities of Antique Jewry. We reason that considering models of social identity could provide us with a fresh perspective of the text, which allows for a new understanding of the complex and dynamic nature of the identities as they appear in the Letter of Aristeas. Introduction The Letter of Aristeas has long been considered the work most emblematic, elucidatory, and declarative of Jewish identity in Hellenistic Egypt. -

The Book of Proverbs Is Not Mysterious, Nor Does It Leave Its Readers Wondering As to Its Purpose

INTRODUCTION The book of Proverbs is not mysterious, nor does it leave its readers wondering as to its purpose. At the very outset we are clearly told the author’s intention. The purpose of these proverbs is to teach people wisdom and discipline, and to help them understand wise sayings. Through these proverbs, people will receive instruction in discipline, good conduct, and doing what is right, just, and fair. These proverbs will make the simpleminded clever. They will give knowledge and purpose to young people. Let those who are wise listen to these proverbs and become even wiser. And let those who understand receive guidance by exploring the depth of meaning in these proverbs, parables, wise sayings, and riddles. NLT, 1:2-6 The book of Proverbs is simply about godly wisdom, how to attain it, and how to use it in everyday living. In Proverbs the words wise or wisdom are used roughly125 times. The wisdom that is spoken of in these proverbs is bigger than raw intelligence or advanced education. This is a wisdom that has to do skillful living. It speaks of understanding how to act and be competent in a variety of life situations. Dr. Roy Zuck’s definition of wisdom is to the point. Wisdom means being skillful and successful in one’s relationships and responsibilities . observing and following the Creator’s principles of order in the moral universe. (Zuck, Biblical Theology of the Old Testament, p. 232) The wisdom of Proverbs is not theoretical.1 It assumes that there is a right way and a wrong way to live. -

Jesus and Second Temple Judaism

SCJR 14, no. 1 (2019): 1-3 Ben C. Blackwell, John K. Goodrich, and Jason Maston, Eds. Reading Mark in Context: Jesus and Second Temple Judaism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018), 286 pp. NICHOLAS A. ELDER [email protected] Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI 53233 Reading Mark in Context is a collection of thirty essays that sequentially in- terprets passages in Mark with specific reference to relevant Second Temple Jewish texts. The volume includes a foreword by N. T. Wright that notes its dual purpose, which is to (1) introduce the reader to Jewish texts from the Second Temple period and (2) provide a “running commentary” on Mark in light of those texts (pp. 14– 15). Preceding the collection’s thirty essays is an introduction from the editors that serves several functions. First, they briefly review historical Jesus scholarship in order to highlight the importance of non-canonical Second Temple Jewish texts for understanding Jesus as he is presented in the gospels. Second, they identify the kind of readers that the volume is primarily intended for, namely beginning to interme- diate students who are evangelical. Third, it offers an introduction to the Second Temple period with reference to major events and writings. As a whole, the collection of essays is well-balanced. Each contribution is ap- proximately seven pages long and is evenly divided between an introduction to a Second Temple Jewish text and an interpretation of Mark in light of that text. A broad swath of Second Temple literature is represented, including the Letter of Aristeas, the Psalms of Solomon, 4 Ezra, the Book of Jubilees, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, and various texts from Qumran, Philo, Josephus, Rabbinic literature, and the Enochic corpus.