The Mathematics of Alice in Wonderland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice in Wonderland

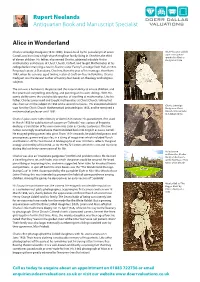

Rupert Neelands Antiquarian Book and Manuscript Specialist Alice in Wonderland Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), known to all by his pseudonym of Lewis Alice Pleasance Liddell, Carroll, was born into a high-church Anglican family living in Cheshire, the third aged seven, photo- graphed by Charles of eleven children. His father, also named Charles, obtained a double first in Dodgson in 1860 mathematics and classics at Christ Church, Oxford, and taught Mathematics at his college before marrying a cousin, Frances Jane “Fanny” Lutwidge from Hull, in 1827. Perpetual curate at Daresbury, Cheshire, from the year of his marriage, then from 1843, when his son was aged twelve, rector at Croft-on-Tees in Yorkshire, Charles Dodgson was the devout author of twenty-four books on theology and religious subjects. The son was a humourist. He possessed the natural ability to amuse children, and first practised storytelling, versifying, and punning on his own siblings. With this comic ability came the unshakeable gravitas of excelling at mathematics. Like his father, Charles junior read and taught mathematics at Christ Church, taking first class honours in the subject in 1854 and a second in classics. His exceptional talent Charles Lutwidge won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855, and he remained a Dodgson at Christ mathematical professor until 1881. Church 1856-60 (John Rich Album, NPG) Charles’s jokes were rather literary or donnish in nature. His pseudonym, first used in March 1856 for publication of a poem on “Solitude”, was a piece of linguistic drollery, a translation of his own name into Latin as Carolus Ludovicus. -

The Other Side of the Lens-Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

The Other Side of the Lens: Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography during the 19th Century is curated by Edward Wakeling, Allan Chapman, Janet McMullin and Cristina Neagu and will be open from 4 July ('Alice's Day') to 30 September 2015. The main purpose of this new exhibition is to show the range and variety of photographs taken by Lewis Carroll (aka Charles Dodgson) from topography to still-life, from portraits of famous Victorians to his own family and wide circle of friends. Carroll spent nearly twenty-five years taking photographs, all using the wet-collodion process, from 1856 to 1880. The main sources of the photographs on display are Christ Church Library, the Metropolitan Museum, New York, National Portrait Gallery, London, Princeton University and the University of Texas at Austin. Visiting hours: Monday: 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Friday: 10:00 am - 1.00 pm. Framed photographs on loan from Edward Wakeling Photographic equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu 2 The Other Side of the Lens Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography ‘A Tea Merchant’, 14 July 1873. IN 2155 (Texas). Tom Quad Rooftop Studio, Christ Church. Xie Kitchin dressed in a genuine Chinese costume sitting on tea-chests portraying a Chinese ‘tea merchant’. Dodgson subtitled this as ‘on duty’. In a paired image, she sits with hat off in ‘off duty’ pose. Contents Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and His Camera 5 Exhibition Catalogue Display Cases 17 Framed Photographs 22 Photographic Equipment 26 3 4 Croft Rectory, July 1856. -

ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Playing Around in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books • Jan Susina Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s love of play and his need for rules came together in his use of popular games as part of the structure of the two famous children’s books, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. The author of this article looks at the interplay between the playing of such games as croquet and cards and the characters and events of the novels and argues that, when reading Carroll (who took a playful approach even in his academic texts), it is helpful to understand games and game play. Charles Dodgson, more widely known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, is perhaps one of the more playful authors of children’s literature. In his career, as a children’s author and as an academic logician and mathematician, and in his personal life, Carroll was obsessed with games and with various forms of play. While some readers are surprised by the seemingly split personality of Charles Dodgson, the serious mathematician, and Lewis Carroll, the imaginative author of children’s books, it was his love of play and games and his need to establish rules and guidelines that effectively govern play that unite these two seemingly disparate facets of Carroll’s personality. Carroll’s two best-known children’s books—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking- Glass and What Alice Found There (1871)—use popular games as part of their structure. In Victoria through the Looking-Glass, Florence Becker Lennon has gone so far as to suggest about Carroll that “his life was a game, even his logic, his mathematics, and his singular ordering of his household and other affairs. -

If Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll)

If Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) had not written Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he’d probably be remembered as a pioneer photographer. But his Oxford ‘day job’ was as Lecturer in Mathematics at Christ Church. What mathematics did he do? C L Dodgson Dodgson time-line 1832 Born in Daresbury, Cheshire 1843 Moves to Croft Rectory, Yorkshire ( ) 1844–49 At Richmond and Rugby Schools Lewis Carroll 1850 Matriculates at Oxford University 1851 Studies at Christ Church, Oxford 1852 Nominated a ‘Student’ at Christ Church Oxford 1854 Long Vacation at Whitby studying with ‘Bat’ Price First Class in Mathematics in his Finals Examinations mathematician 1856 Mathematical Lecturer at Christ Church Adopts the pseudonym Lewis Carroll “What I look like when I’m lecturing. The merest sketch, you will allow – Develops an interest in photography yet still I think there’s something grand 1860 Notes on the First Two Books of Euclid In the expression of the brow 1861 The Formulae of Plane Trigonometry and in the action of the hand.” 1862 Boat trip to Godstow with the C L Dodgson Liddell sisters 1865 The Dynamics of a Parti-cle Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 1866 ‘Condensation of Determinants’ read to the Royal Society 1867 An Elementary Treatise on Determinants 1868 The Fifth Book of Euclid 1871 Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There 1873 A Discussion of the Various Methods of Procedure in Conducting Elections 1876 The Hunting of the Snark 1879 Euclid and his Modern Rivals 1881 Resigns Mathematical Lecturership 1882 Euclid, Books I, II 1883 Lawn Tennis Tournaments 1884 The Principles of Parliamentary Representation 1885 A Tangled Tale 1886 The Game of Logic 1888 Curiosa Mathematica, I. -

In.T-Ro"D :U'g Ti-O N

.IN.T-RO "D :U'G TI-O N "No! No! The-a'd ventures-, first," sajd'tlie Gryphon in .an impatient: tone: ."ex- planations, take'such a dreadful time.":('The'L6bster-Quadrille')'". •-. -. ' "Even a joke should Have some meaning- -and a child's'more important than a'joke, I hope." {'Queen Alice'}1 .. i: Tlie Child, Nonsense and Meaning '"The'adventures'..first'".,\says Carroll's' Gryphon; \vitli,his^dread of 'explanations', arid. aU1. readers: know;, this-is'.the'right orderuYet rritro^' duction's'incvitably "come before,adventures.and'intrbdu'crions.tend .to mean explanations:-Lbts of-things'happen:the.^\Tong.,way .rouh'd in' these .texts -?;1"Sentence-first —^"erdic^afterivards'i'i'-sliouts the. Queen of Hearts3'—.so:readerS'vWho'.share: the.Gryplion's:priorities^ can al\vays: read the introduction-after th'e:stories,"or:not at;all/You simplytfollow the instructions of.the King of.Hearts: "'Begin-at'the-bcgirining'..'-. ..and go on;tilTy6urcbme.io the-endr.then stop'".3. ••LJ-.: ..._ ..; ; .• . .;-.:i. : Yet,Cafrolls:herd)iie,'atLthc hearfbf,tHese:adventuresj :s, very.much concerned with'.'questions-of 'mean ing:: iVheii sKe 'dreamily: finds her way tb'the other side of.the looking-glass, one~:of the;first things she encounters "Is a. poem:'call ed:'Jabben,vocky.>.':After.-.reading ."it, '.Alice remarks '"It seems very/pretty.1.-/.'-but it's-rather hard to ^understand!'." '"Somehowit-'fills-my:head:.\vith;ideas''',^he reflects; '"only 1''don't exactly 'la'iow what they>are!".!1 " : ..•L-jiurT't ,- -.'- . ..iL:-. .••-.. -/'v,.- In this-Tespectfthe'nonsensical.mirrbr-poem;'Jabber\vock;'>.stands'asv a.mirror:of the classic literary,double-act.o£whicKJt is.'part: All readers- Q{ Alice's Adventures.in'.Wondcrlimd 'and~Tliroiigh''the--Lookwg-'Clas$, those. -

Lewis Carroll (Charles L

LEWIS CARROLL (CHARLES L. DODGSON) a selection from The Library of an English Bibliophile Peter Harrington london VAT no. gb 701 5578 50 Peter Harrington Limited. Registered office: WSM Services Limited, Connect House, 133–137 Alexandra Road, Wimbledon, London SW19 7JY. Registered in England and Wales No: 3609982 Design: Nigel Bents; Photography Ruth Segarra. Peter Harrington london catalogue 119 LEWIS CARROLL (CHARLES L. DODGSON) A collection of mainly signed and inscribed first and early editions From The Library of an English Bibliophile All items from this catalogue are on display at Dover Street mayfair chelsea Peter Harrington Peter Harrington 43 Dover Street 100 Fulham Road London w1s 4ff London sw3 6hs uk 020 3763 3220 uk 020 7591 0220 eu 00 44 20 3763 3220 eu 00 44 20 7591 0220 usa 011 44 20 3763 3220 usa 011 44 20 7591 0220 Dover St opening hours: 10am–7pm Monday–Friday; 10am–6pm Saturday www.peterharrington.co.uk FOREWORD In 1862 Charles Dodgson, a shy Oxford mathematician with a stammer, created a story about a little girl tumbling down a rabbit hole. With Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), children’s literature escaped from the grimly moral tone of evangelical tracts to delight in magical worlds populated by talking rabbits and stubborn lobsters. A key work in modern fantasy literature, it is the prototype of the portal quest, in which readers are invited to follow the protagonist into an alternate world of the fantastic. The Alice books are one of the best-known works in world literature. They have been translated into over one hundred languages, and are referenced and cited in academic works and popular culture to this day. -

Carrollian Language Arts & Rhetoric

CARROLLIAN LANGUAGE ARTS & RHETORIC: DODGSON’S QUEST FOR ORDER & MEANING, WITH A PORPOISE By Madonna Fajardo Kemp Approved: _____________________________________ __________________________________ Rebecca Ellen Jones Susan North UC Foundation Associate Professor Director of Composition of Rhetoric and Composition Committee Member Director of Thesis _____________________________________ Charles L. Sligh Assistant Professor of Literature Committee Member _____________________________________ __________________________________ Herbert Burhenn A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Dean of the Graduate School CARROLLIAN LANGUAGE ARTS & RHETORIC: DODGSON’S QUEST FOR ORDER & MEANING, WITH A PORPOISE By Madonna Fajardo Kemp A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English: Rhetoric and Composition The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, TN December 2011 ii Copyright © 2011 By Madonna Fajardo Kemp All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Lewis Carroll (Rev. Charles Dodgson) is a language specialist who has verifiably altered our lexicon and created fictional worlds that serve as commentary on our ability to effectively create meaning within our existing communicative systems. This ability to create language and illustrations of everyday language issues can be traced back to his personal quest for order and meaning; the logician and teacher has uncovered the accepted language and language practices that can result in verbal confusion and ineffective speech, as well as the accepted practices that can help us to avoid verbal confusion and social conflict—all of which reveals a theorist in his own right, one who aides our understanding of signification and pragmatic social skills. Dodgson’s fictive representations of our ordinary language concerns serve as concrete examples of contextual language interactions; therefore, they serve as appropriate material for the teaching of rhetorical theory and, most especially, language arts. -

Lewis Carroll � Wikipedia, La Enciclopedia Libre Página 1 De 7

Lewis Carroll - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre Página 1 de 7 Lewis Carroll De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre Lewis Carroll es el seudónimo por el que es conocido en la historia de la literatura Charles Lewis Carroll Lutwidge Dodgson (Daresbury, Cheshire, 27 de enero de 1832 – Guildford, Surrey, 14 de enero de 1898), diácono anglicano, lógico, matemático, fotógrafo y escritor británico, conocido sobre todo por su obra Alicia en el país de las maravillas . Contenido ■ 1 Biografía ■ 2 Carroll y la fotografía ■ 3 Carrera literaria ■ 4 Carroll y las matemáticas ■ 5 Controversias e incógnitas ■ 5.1 Consumo de estupefacientes ■ 5.2 Sacerdocio Lewis Carroll, fotografía tomada por él mismo ■ 6 Véase también ■ 7 Referencias Nombre completo Charles Lutwidge Dodgson ■ 8 Bibliografía Nacimiento 27 de enero de 1832 ■ 8.1 Algunas obras de Lewis Daresbury, Cheshire, Reino Carroll Unido ■ 8.2 Correspondencia ■ 8.3 En inglés Defunción 14 de enero de 1898 (65 años) ■ 8.4 Bibliografía pasiva Guilford, Surrey, Reino Unido ■ 9 Enlaces externos Seudónimo Lewis Carroll Ocupación Escritor, diácono, matemático, lógico, fotógrafo Biografía Nacionalidad Británica Obras notables Alicia en el país de las Los antepasados de Dodgson procedían principalmente del norte de Inglaterra, con maravillas , algunas conexiones irlandesas. Conservadores A través del espejo y lo que y miembros de la High Church anglicana, la Alicia encontró allí mayoría de ellos se dedicaron a las dos profesiones características de la clase media-alta inglesa: el ejército y la Iglesia. Su bisabuelo, llamado también Charles Dodgson, llegó a ser obispo; su abuelo, otro Charles, fue capitán del ejército y murió en batalla en 1803, cuando sus dos hijos eran todavía muy pequeños. -

Lewis Carroll - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Lewis Carroll - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Lewis Carroll(27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898) Charles Lutwidge Dodgson better known by the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, was an English author, mathematician, logician, Anglican deacon and photographer. His most famous writings are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, as well as the poems "The Hunting of the Snark" and "Jabberwocky", all examples of the genre of literary nonsense. He is noted for his facility at word play, logic, and fantasy, and there are societies dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life in many parts of the world, including the United Kingdom, Japan, the United States, and New Zealand. Antecedents Dodgson's family was predominantly northern English, with Irish connections. Conservative and High Church Anglican, most of Dodgson's ancestors were army officers or Church of England clergymen. His great-grandfather, also Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become Bishop of Elphin. His grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in Ireland in 1803, when his two sons were hardly more than babies. His mother's name was Frances Jane Lutwidge. The elder of these sons – yet another Charles Dodgson – was Carroll's father. He reverted to the other family tradition and took holy orders. He went to Westminster School, and thence to Christ Church, Oxford. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. -

Lewis in Storyland

LEWIS IN STORYLAND JIM PUDER Saratoga, California It is the peculiar fate of a few celebrated authors, whose personalities as well as whose works fasci- nate us, to experience, posthumously, new literary careers as characters in other writers' fiction. Such an author is Charles Dodgson, better known to many as Lewis Carroll, wllose first of a score of appearances as a character in fiction occurred about 70 years ago. Hardcore Carroll devotees, of course, already know all about all such fictional "LC" apparitions, but more casual Carroll enthusiasts may thank Seattle writer N. Lee for compiling a list of eleven novels and one feature film in which Dodgson figures as a major or a minor character. (1) Of her list, Lee wryly remarks that one could, for that matter, "...argue that ALL portrayals of Lewis Carroll are fictional, including his letters and diaries [and] much of Carroll scholar- ship. o " No doubt; nevertheless, here is her list, which I have taken the liberty of rearranging and aug- menting with informatioil fiom other sources, and in which I have replaced her comments with my own: FILM Dreamchild British, 1985. DVD. With Coral Browne, Ian Holm and Peter Gallagher. Directed by Gavin Millar; written by Dennis Potter. While no one doubts that young Alice Liddell (2) was Charles Dodgson's muse and his inspiration for the heroine in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, the precise nature of the Dodgson- Liddell relation- ship, particularly on Dodgson's part, remains after a century and a half a seemingly endlessly fascinating and disputable topic, and it is the subject matter of Dreamchild, 111 it, Dodgson is depicted as a shy, lone- ly, socially awkward bachelor to whom his friendship with Liddell comes to mean a great deal, and his feelings for her are portrayed as being platonic, sincere, touching, and ultimately sad. -

Lewis Carroll

Alice in Wonderland (Poetry in Motion) Study Guide A Ballet Presented by State Street Ballet of Santa Barbara Sponsored by the Valley Performing Arts Council Janet M. Kelly [email protected] 1 Table of Contents 3 Letter to Educators 4-6 Biographical Information about Lewis Carroll 7 The “Real” Alice in Wonderland, Alice Liddel 8-10 Summary of the story “Alice in Wonderland” 11-12 State Street Ballet of Santa Barbara Ballet Information 13-14 “Jabberwocky” Poem and Activities 15-16 Characters in Alice in Wonderland Critical thinking about the symbolism of the characters 17-18 Poetry in Motion 19-20 “White Rabbit” by Jefferson Airplane, Woodstock, 1969 A critical thinking exercise for older students 21 Bibliography 2 Dear Educators, State Street Ballet of Santa Barbara’s version of Alice in Wonderland is one of the most student friendly ballets I’ve witnessed. It is appropriate for very young students who will take the story literally. It is also appropriate for older students who may want to delve into the historical context, innuendo, and figurative nature of Alice in Wonderland. The costumes and choreography tell a wordless story so well that students who have never seen ballet will comprehend what the dancers are trying to convey. I’ve titled this Study Guide as “Poetry in Motion” because I found that movement can tell a story, or help interpret a poem, so the meaning of the writing is understandable for even the youngest student. This study guide has background information, and a variety of points-of-view that can appeal to young students as well as adults. -

Alice's Evidence: Lewis Carroll and Autism

Alice’s Evidence: A New Look at Autism by Robert B. Waltz To Elizabeth Rosenberg Catie Jo Pidel Patricia Rosenberg Who showed me where I was wrong and to Sarah Jane and her son wherever you are in hopes it may help make a better world for them Eyes so wide with wonder Looking for the key, In the tongues of others Zealously she sees A tale with hidden meaning Battling to be free. Ears will hear the story Told where’er she goes; How many other hearers Rejoice in what she knows! Oh, can we ever match Such a blooming rose? Ever may she tell the tale, New words for the old, Bearing on her journey Each precious word untold, Roving the world over Giving gifts like gold. Passing minstrels tell a tale, A tale of joy and love, !at is carried on the wind Rung down from high above. I would tell you this story, Carried by "ying birds, It is a tale of treasure — A treasure beyond words. Read to me this story, Oh, may it come to you! Send this joy upon her; Ever may it come true. Now may your heart be joyful, By land and sea and air, Even amid the sorrows Real folk ever must share, Guard her from every care! Can you hear the music Afar upon the wind? !e lonesome #ddle playing In the newgrass string band? Every note is perfect; Joy in every tune — Old songs, new songs, stories, Played under sun and moon. Inspired is the music — Dreams are in her hands; Ever may they come true, Like songs of many lands.