IHEWHITEEHIGHT 4 Sttdy of C. L . DODGSON (LWLS CARROLL)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Return of the Jabber W Ock Graham / Neale

THE RETURN OF THE JABBERWOCK THE RETURN OF A brave little boy sets off on an adventure to find the Jabberwock, just like his great grandfather before him. But what creatures will he encounter in mysterious Tulgey Wood? Illustrated by David Neale Written by Oakley Graham GRAHAM / NEALE RRP £5.99 For more Top That! books visit our website: Published by Top That! Publishing plc www.topthatpublishing.com Tide Mill Way, Woodbridge, Suffolk, IP12 1AP, UK Copyright © 2013 Top That! Publishing plc All rights reserved 0 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 Printed and bound in China XXX-XXX-XX-XXXX-XX Published by Top That! Publishing plc Tide Mill Way, Woodbridge, Suffolk, IP12 1AP, UK www.topthatpublishing.com Copyright © 2013 Top That! Publishing plc All rights reserved 0 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 Printed and bound in China Creative Director – Simon Couchman Editorial Director – Daniel Graham Illustrated by David Neale Written by Oakley Graham All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Neither this book nor any part or any of the illustrations, photographs or reproductions contained in it shall be sold or disposed of otherwise than as a complete book, and any unauthorised sale of such part illustration, photograph or reproduction shall be deemed to be a breach of the publisher’s copyright. ISBN 978-1-78244-171-7 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Printed and bound in China Written by Oakley Graham Illustrated by David Neale For the magnificent seven; Jazz, Amber, Noah, Oakie, Jemima, Isis & Isadora. -

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

THE LAND BEYOND the MAGIC MIRROR by E

GREYHAWK CASTLE DUNGEON MODULE EX2 THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR by E. Gary Gygax AN ADVENTURE IN A WONDROUS PLACE FOR CHARACTER LEVELS 9-12 No matter the skill and experience of your party, they will find themselves dazed and challenged when they pass into The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror! Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc. and in Canada by Random House of Canada Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. Distributed in the United Kingdom by TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. AD&D and WORLD OF GREYHAWK are registered trademarks owned by TSR Hobbies, Inc. ©1983 TSR Hobbies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. TSR Hobbies, Inc. TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. POB 756 The Mill, Rathmore Road Lake Geneva, Cambridge CB14AD United Kingdom Printed in U.S.A. WI 53147 ISBN O 88038-025-X 9073 TABLE OF CONTENTS This module is the companion to Dungeonland and was originally part of the Greyhawk Castle dungeon complex. lt is designed so that it can be added to Dungeonland, used alone, or made part of virtually any campaign. It has an “EX” DUNGEON MASTERS PREFACE ...................... 2 designation to indicate that it is an extension of a regular THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR ............. 4 dungeon level—in the case of this module, a far-removed .................... extension where all adventuring takes place on another plane The Magic Mirror House First Floor 4 of existence that is quite unusual, even for a typical AD&D™ The Cellar ......................................... 6 Second Floor ...................................... 7 universe. This particular scenario has been a consistent ......................................... -

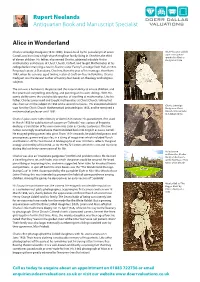

Alice in Wonderland

Rupert Neelands Antiquarian Book and Manuscript Specialist Alice in Wonderland Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), known to all by his pseudonym of Lewis Alice Pleasance Liddell, Carroll, was born into a high-church Anglican family living in Cheshire, the third aged seven, photo- graphed by Charles of eleven children. His father, also named Charles, obtained a double first in Dodgson in 1860 mathematics and classics at Christ Church, Oxford, and taught Mathematics at his college before marrying a cousin, Frances Jane “Fanny” Lutwidge from Hull, in 1827. Perpetual curate at Daresbury, Cheshire, from the year of his marriage, then from 1843, when his son was aged twelve, rector at Croft-on-Tees in Yorkshire, Charles Dodgson was the devout author of twenty-four books on theology and religious subjects. The son was a humourist. He possessed the natural ability to amuse children, and first practised storytelling, versifying, and punning on his own siblings. With this comic ability came the unshakeable gravitas of excelling at mathematics. Like his father, Charles junior read and taught mathematics at Christ Church, taking first class honours in the subject in 1854 and a second in classics. His exceptional talent Charles Lutwidge won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855, and he remained a Dodgson at Christ mathematical professor until 1881. Church 1856-60 (John Rich Album, NPG) Charles’s jokes were rather literary or donnish in nature. His pseudonym, first used in March 1856 for publication of a poem on “Solitude”, was a piece of linguistic drollery, a translation of his own name into Latin as Carolus Ludovicus. -

Cweb Study Guide

" " " " " Alice in Wonderland " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " STUDY " GUIDE " " Designed and developed" " " by: Lexi Barnett" " : Meet the Author Lewis Carrol Lewis Carroll was the pseudonym of Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a lecturer in mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford, who lived from 1832 to 1898. Carroll’s physical deformities, partial deafness, and irrepressible stammer made him an unlikely candidate for producing one of the most popular and enduring children’s fantasies in the English language. Carroll’s unusual appearance caused him to behave awkwardly around other adults, and his students at Oxford saw him as a stuffy and boring teacher. Underneath Carroll’s awkward exterior, however, lay a brilliant and imaginative artist. Carroll’s keen grasp of mathematics and logic inspired the linguistic humor and witty wordplay in his stories. Additionally, his unique understanding of children’s minds allowed him to compose imaginative fiction that appealed to young people. In 1856, Carroll and met the Liddell family. During their frequent afternoon boat trips on the river, Carroll told the Liddells fanciful tales. Alice quickly became Carroll’s favorite of the three girls, and he made her the subject of the stories that would later became Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Almost ten years after first meeting the Liddells, Carroll compiled the stories and .1 submitted the completed manuscript for publication. pg If you lived all by yourself,Translating what would your housethe lookJabberwocky! like? Draw your ideal house below: There are many poems recited in Alice in Wonderland- one of the most bizarre is the Jabberwocky! What do you think it means? Write your translation of the words to the right of the poem " ’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

Submission and Agency, Or the Role of the Reader in the First Editions of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderla

Submission and Agency, or the Role of the Reader in the First Editions of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871) Virginie Iché To cite this version: Virginie Iché. Submission and Agency, or the Role of the Reader in the First Editions of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871). Cahiers Victoriens et Edouardiens, Montpellier : Centre d’études et de recherches victoriennes et édouardiennes, 2016, 84, pp.Texte intégral en ligne. 10.4000/cve.2962. hal-03062880 HAL Id: hal-03062880 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03062880 Submitted on 27 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens 84 Automne | 2016 Object Lessons: The Victorians and the Material Text Submission and Agency, or the Role of the Reader in the First Editions of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through -

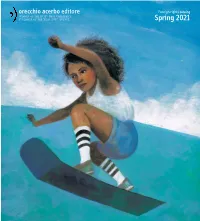

Orecchio Acerbo Rights List Spring 2021

orecchio acerbo editore Foreign rights catalog Winner of the BoP · Best Children’s PuBlisher of the Year 2017, euroPe Spring 2021 picture books daybrEak NEW by Daniel Fehr illustrations Elena Rotondo for children 4 years and older pp. 28 | cm. 23 x 21 ISBN 9788832070651 | July 2021 today NEW by Daniel Fehr big quEstioNs | grEat advENturEs illustrations Simone Rea WaitiNg for Walt for children 4 years and older by Daniel Fehr The story is about a young boy and his father. pp. 64 | cm. 17 x 24 illustrations Maja Celjia In the middle of the night they leave their house. ISBN 9788832070590 | April 2021 for children 5 years and older For the boy it is the first time that he leaves home pp. 32 | cm. 24 x 32 | May 2020 at this time of the night when normally uNdEr thE gazE of timE | rEcouNtiNg thE prEsENt he is asleep. As they walk through the forest storiEs of thE visioNary aNd thE absurd laughtEr aNd smilEs the flashlight of the boy “turns on” part A father who is leaving. Two brothers. A long wait. of the vegetation and at the same time the rest But together it is easier, together it is easy disappear. He turns off the flashlight and “turns on” to be strong. The older brother reads books Two kids are waiting for Walt. But who is Walt? all his senses: he experiences the darkness, to the younger one who can’t read yet but can And, if Walt was there with them, what would the sounds of the forest, the sound of his father, at least choose the book; then they go together they all do together? They would have a lot the roughness of the ground, the smells… on a secret mission: is every mission of spies of fun, because when he is there he always He dares not ask for the space and time secret? Then one goes to play football, the other has crazy ideas. -

The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, the Hunting of the Snark, a Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online

yaTOs (Download pdf) The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online [yaTOs.ebook] The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Pdf Free Lewis Carroll ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1419651 in Books 2011-11-07Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 1.70 x 6.50 x 9.30l, 1.70 #File Name: 0890097003440 pages | File size: 46.Mb Lewis Carroll : The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Wonderful books for a wonderful priceBy llamapyrLewis Carroll must've been the greatest children's book author of his time. I really admire his writing style and the creativity of his books, having grown up on them since I was 6. I've got a bunch of his novels in hardcover and paperback sitting on my shelves, so it seemed only right to add some digital versions to my library :)Anyway, I came here looking for Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and found this set, and for a mere 99 cents it seemed worth a look. -

The Other Side of the Lens-Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

The Other Side of the Lens: Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography during the 19th Century is curated by Edward Wakeling, Allan Chapman, Janet McMullin and Cristina Neagu and will be open from 4 July ('Alice's Day') to 30 September 2015. The main purpose of this new exhibition is to show the range and variety of photographs taken by Lewis Carroll (aka Charles Dodgson) from topography to still-life, from portraits of famous Victorians to his own family and wide circle of friends. Carroll spent nearly twenty-five years taking photographs, all using the wet-collodion process, from 1856 to 1880. The main sources of the photographs on display are Christ Church Library, the Metropolitan Museum, New York, National Portrait Gallery, London, Princeton University and the University of Texas at Austin. Visiting hours: Monday: 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Friday: 10:00 am - 1.00 pm. Framed photographs on loan from Edward Wakeling Photographic equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu 2 The Other Side of the Lens Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography ‘A Tea Merchant’, 14 July 1873. IN 2155 (Texas). Tom Quad Rooftop Studio, Christ Church. Xie Kitchin dressed in a genuine Chinese costume sitting on tea-chests portraying a Chinese ‘tea merchant’. Dodgson subtitled this as ‘on duty’. In a paired image, she sits with hat off in ‘off duty’ pose. Contents Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and His Camera 5 Exhibition Catalogue Display Cases 17 Framed Photographs 22 Photographic Equipment 26 3 4 Croft Rectory, July 1856. -

ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Playing Around in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books • Jan Susina Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s love of play and his need for rules came together in his use of popular games as part of the structure of the two famous children’s books, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. The author of this article looks at the interplay between the playing of such games as croquet and cards and the characters and events of the novels and argues that, when reading Carroll (who took a playful approach even in his academic texts), it is helpful to understand games and game play. Charles Dodgson, more widely known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, is perhaps one of the more playful authors of children’s literature. In his career, as a children’s author and as an academic logician and mathematician, and in his personal life, Carroll was obsessed with games and with various forms of play. While some readers are surprised by the seemingly split personality of Charles Dodgson, the serious mathematician, and Lewis Carroll, the imaginative author of children’s books, it was his love of play and games and his need to establish rules and guidelines that effectively govern play that unite these two seemingly disparate facets of Carroll’s personality. Carroll’s two best-known children’s books—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking- Glass and What Alice Found There (1871)—use popular games as part of their structure. In Victoria through the Looking-Glass, Florence Becker Lennon has gone so far as to suggest about Carroll that “his life was a game, even his logic, his mathematics, and his singular ordering of his household and other affairs.