Vol. 65. ] Oracia~ Xroslon I~ ~0RZ~R WAL~S. 281 1S. GLACIAL EI~Oslon in NORT~R WALES. by Prof. WILLIA~ M01iris DAWS, For. Corr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Wales' Highest Mountain the Perfect Starter Peak for Kids?

SNOWDON FOR ALL CHILD’S PLAY Is Wales’ highest mountain the perfect starter peak for kids? We sent a rock star to find out... WORDS & PHOTOGRAPHS PHOEBE SMITH ver half a million an ideal first mountain for kids visitors a year would to climb. Naturally, we wanted to suggest the cat is well put that theory to the test, so we and truly out of the went in search of an adventurous bag with Snowdon. family looking for their first taste Arguably, it’s the perfect of proper mountain walking. We mountain for walkers. weren’t expecting that search to Undeniably, it’s one of lead us to a BBC radio presenter OEurope’s most spectacular. This is who also happened to be the lead a peak of extraordinary, unrivalled singer of a multi-million-selling versatility, one that’s historically 1990s rock band. But that’s been used as a training ground exactly what happened. for Everest-bound mountaineers, The message arrived quite but also one where you could unexpectedly one Wednesday achievably stroll with your afternoon. Scanning through my children to the summit. emails, it was a pretty normal day. Then I saw it, the There are no fewer than 10 recognised ways one that stood out above the rest. The subject line to walk or scramble to Snowdon’s pyramidal read: ‘SNOWDONIA – February half-term?’ 1085m top. The beginner-friendly Llanberis Path The message was from Cerys Matthews, the offers the most pedestrian ascent; the South Ridge former frontwoman of rock band Catatonia and holds the key to the mountain’s secret back door; a current BBC Radio 6 Music presenter, who I’d while the notoriously nerve-zapping and razor-sharp accompanied on a wild camping trip a few months ridgeline of Crib Goch is reserved for those with a earlier. -

GLACIATION in SNOWDONIA by Paul Sheppard

GeoActiveGeoActive 350 OnlineOnline GLACIATION IN SNOWDONIA by Paul Sheppard This unit can be used These remnants of formerly much higher mountains have since been independently or in Conwy conjunction with OS 1:50,000 eroded into what is seen today. The Bangor mountains of Snowdonia have map sheet 115. N Caernarfon Llanrwst been changed as a result of aerial Llanberis Capel Curig Snowdon Betws y Coed (climatic) and fluvial (water) HE SNOWDONIA OR ERYRI (Yr Wyddfa) Beddgelert Blaenau erosion that always act upon a NATIONAL PARK, established Ffestiniog T Porthmadog landscape, but in more recent SNOWDONIA Y Bala in 1951, was the third National NATIONAL Harlech geological times the effects of ice PARK Park to be established in England have had a major impact upon the and Wales following the 1949 Barmouth Abermaw Dolgellau actual land surface. National Parks and Access to the Cadair Countryside Act (Figure 1). It Idris Tywyn 2 Machynlleth Glaciation covers an area of 2,171 km (838 Aberdyfi 0 25 km square miles) of North Wales and Ice ages have been common in the British Isles and northern Europe, encompasses the Carneddau and Figure 1: Snowdonia National Park Glyderau mountain ranges. It also with 40 having been identified by includes the highest mountain in important to look first at the geologists and geomorphologists. England and Wales, with Mount geological origins of the area, as The most recent of these saw Snowdon (Yr Wyddfa in Welsh) this provides the foundation upon Snowdonia covered with ice as reaching a height of 1,085 metres which ice can act. -

Self Permitting)

Final Permitting Decisions for NRWs Own Applications (Self Permitting) May-17 Permit Number Permit Regime Permit Type Permit Holder Site Address Activity Description Decision Determination Date Eryri SSSI Eryri/Snowdonia Geomorphological restoration of approximately 2238756 WCA Assent Natural Resources Wales Issued 09/05/2017 SAC 200m of the Nant Peris (river) Coedydd Nedd a Mellte SAC Bridge and culvert installation, path and 2238618 WCA Assent Natural Resources WalesDyffrynoedd Nedd a Mellte a Moel Issued 10/05/2017 drainage works. Pendery SSSI To remove gorse from both sides of the Dysynni 2239122 WCA Assent Natural Resources WalesBroadwater SSSI Issued 15/05/2017 Flood Defence embankment 2239122 WCA Assent Natural Resources WalesBroadwater SSSI Routine grass cutting of flood embankmen Issued 15/05/2017 MSc research project regarding capture 2239503 WCA Assent Natural Resources WalesCoedydd Aber SSSI/SAC success rates of Fineren bodygrip box and Trap Issued 18/05/2017 Man squirrel traps Mynydd Tir y Cwmwd a'r Glannau at Using a 360 degree excavator from the beach Garreg yr Imbill SSSI Pen Llyn ar 2240089 WCA Assent Natural Resources Wales to reposition displaced boulder stone back onto Issued 24/05/2017 Sarnau/Lleyn Peninsula and the the sea defence Sarnau SAC 2240223 WCA Assent Natural Resources WalesBroadwater SSSI Embankment protection works Issued 25/05/2017 Apr-17 Permit Number Permit Regime Permit Type Permit Holder Site Address Activity Description Decision Determination Date Sand clearance along existing access corridor Morfa -

Rock Trails Snowdonia

CHAPTER 6 Snowdon’s Ice Age The period between the end of the Caledonian mountain-building episode, about 400 million years ago, and the start of the Ice Ages, in much more recent times, has left little record in central Snowdonia of what happened during those intervening aeons. For some of that time central Snowdonia was above sea level. During those periods a lot of material would have been eroded away, millimetre by millimetre, year by year, for millions of years, reducing the Alpine or Himalayan-sized mountains of the Caledonides range to a few hardened stumps, the mountains we see today. There were further tectonic events elsewhere on the earth which affected Snowdonia, such as the collision of Africa and Europe, but with much less far-reaching consequences. We can assume that central Snowdonia was also almost certainly under sea level at other times. During these periods new sedimentary rocks would have been laid down. However, if this did happen, there is no evidence to show it that it did and any rocks that were laid down have been entirely eroded away. For example, many geologists believe that the whole of Britain must have been below sea level during the era known as the ‘Cretaceous’ (from 145 million until 60 million years ago). This was the period during which the chalk for- mations were laid down and which today crop out in much of southern and eastern Britain. The present theory assumes that chalk was laid down over the whole of Britain and that it has been entirely eroded away from all those areas where older rocks are exposed, including central Snowdonia. -

The Far Side of the Sky

The Far Side of the Sky Christopher E. Brennen Pasadena, California Dankat Publishing Company Copyright c 2014 Christopher E. Brennen All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language or computer language, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission from Christopher Earls Brennen. ISBN-0-9667409-1-2 Preface In this collection of stories, I have recorded some of my adventures on the mountains of the world. I make no pretense to being anything other than an average hiker for, as the first stories tell, I came to enjoy the mountains quite late in life. But, like thousands before me, I was drawn increasingly toward the wilderness, partly because of the physical challenge at a time when all I had left was a native courage (some might say foolhardiness), and partly because of a desire to find the limits of my own frailty. As these stories tell, I think I found several such limits; there are some I am proud of and some I am not. Of course, there was also the grandeur and magnificence of the mountains. There is nothing quite to compare with the feeling that envelopes you when, after toiling for many hours looking at rock and dirt a few feet away, the world suddenly opens up and one can see for hundreds of miles in all directions. If I were a religious man, I would feel spirits in the wind, the waterfalls, the trees and the rock. Many of these adventures would not have been possible without the mar- velous companionship that I enjoyed along the way. -

Snowdonia Green Key Strategy Appraisal Document and User Survey Snowdonia Active – Eryri Bywiol Feb/March 2002 V3.00

Snowdonia Green Key Strategy Appraisal Document and User Survey Snowdonia Active – Eryri Bywiol Feb/March 2002 V3.00 1 Snowdonia-Active Snowdonia-Active is a recently formed group of independent freethinking business people from within the Gwynedd, Môn and the rural Conwy area. We have come together as a result of sharing a common desire to better promote and safeguard Adventure Tourism and associated Outdoor Industries within our geographical area. We see a need for a unifying group bringing together all the elements that give the Adventure Tourism and associated Outdoor Industries their special Snowdonia magic. The group represents a broad spectrum of those elements, from Freelance Instructors, Heads of Outdoor Centres and Management Development Companies to Equipment Manufacturers, Retailers and Service Industries. We believe that the best way to protect the interests of our industry, it’s customers and the environment is by coming together to promote and develop the valuable contribution that we make to the local economy. 2 Introduction This report was co-ordinated by Snowdonia-Active to provide a structured insight into the possible impact of the proposed Snowdonia Green Key Strategy (GKS) upon local outdoor orientated businesses and outdoor adventure/recreational users of Northern Snowdonia. It was deeply felt and vociferously expressed that the Green Key Strategy failed to consult with these user groups. Since the GKS argues strongly for reforms to aid the economic development of the area, the lack of consultation with the outdoor business sector has resulted in many of the positive aspects of the strategy being overshadowed by controversy surrounding the plans for the enforced Park & Ride scheme. -

Glaslyn, Dwyryd, Artro Catchment Management Plan Action Plan: 1996

-N A/^-5 GLASLYN, DWYRYD, ARTRO CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN ACTION PLAN: 1996 at m ’>*v *- Blaenau ^Ffestiniog thmadoi i Harlech CONTACTING THE NRA The national head office of the N R A is in Bristol Enquiries about the Glaslyn, Dwyryd, Artro Catchment Management Plan should be directed to: Telephone: 01454 - 624400 Kelvin Graham, The Welsh Region head office is in Cardiff Area Catchment Planner, Telephone: 01222 - 770088 Ffordd Penlan, The Area Manager for the Northern Area of the Welsh Parc Menai, Region is: Bangor, G w ynedd, Steve Brown, L L 554B P Ffordd Penlan, Parc Menai, You should note that the N R A will be merged into B angor, the Environment Agency after 1st April 1996. G w y ne d d . However, responses to this report should be sent to the LL57 4B P same address, as above. NRA Copyright Waiver. This report is intended to be used widely and may be quoted, copied or reproduced in any way, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and due acknowledgement is given to the National Rivers Authority. Acknowledgement:- Maps are based on the 1992 Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 scale map with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s stationary Office © Copyright. WE 2 96 1.5k E AQMV Awarded for excellence in GLASLYN, DWYRYD, ARTRO CATCHMENT Gajp" i BK. CATCHMENT STATISTICS Area.................................. ,508km2 Population......................... 19,000 Area at flood risk............... ..1,700Ha Average rainfall................. ..3266mm River quality...................... 72.2km Very Good 3.2km Fair KEY Estuary quality................... .29.9 km Good ..... CATCHMENT BOUNDARY 0.5km Fair ----- A ROAD Designated fisheries......... -

Paul Gannon 2Nd Edition

2nd Edition In the first half of the book Paul discusses the mountain formation Paul Gannon is a science and of central Snowdonia. The second half of the book details technology writer. He is author Snowdonia seventeen walks, some easy, some more challenging, which bear Snowdonia of the Rock Trails series and other books including the widely evidence of the story told so far. A HILLWalker’s guide TO THE GEOLOGY & SCENERY praised account of the birth of the Walk #1 Snowdon The origins of the magnificent scenery of Snowdonia explained, and a guide to some electronic computer during the Walk #2 Glyder Fawr & Twll Du great walks which reveal the grand story of the creation of such a landscape. Second World War, Colossus: Bletchley Park’s Greatest Secret. Walk #3 Glyder Fach Continental plates collide; volcanoes burst through the earth’s crust; great flows of ash He also organises walks for hillwalkers interested in finding out Walk #4 Tryfan and molten rock pour into the sea; rock is strained to the point of catastrophic collapse; 2nd Edition more about the geology and scenery of upland areas. Walk #5 Y Carneddau and ancient glaciers scour the land. Left behind are clues to these awesome events, the (www.landscape-walks.co.uk) Walk #6 Elidir Fawr small details will not escape you, all around are signs, underfoot and up close. Press comments about this series: Rock Trails Snowdonia Walk #7 Carnedd y Cribau 1 Paul leads you on a series of seventeen walks on and around Snowdon, including the Snowdon LLYN CWMFFYNNON “… you’ll be surprised at how much you’ve missed over the years.” Start / Finish Walk #8 Northern Glyderau Cwms A FON NANT PERIS A4086 Carneddau, the Glyders and Tryfan, Nant Gwynant, Llanberis Pass and Cadair Idris. -

Ucheldir Y Gogledd Part 1: Description

LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREA 1: UCHELDIR Y GOGLEDD PART 1: DESCRIPTION SUMMARY OF LOCATION AND BOUNDARIES Ucheldir y Gogledd forms the first significant upland landscape in the northern part of the National Park. It includes a series of peaks - Moel Wnion, Drosgl, Foel Ganol, Pen y Castell, Drum, Carnedd Gwenllian, Tal y Fan and Conwy Mountain rising between 600 and 940m AOD. The area extends from Bethesda (which is located outside the National Park boundary) in the west to the western flanks of the Conwy valley in the east. It also encompasses the outskirts of Conwy to the north to form an immediate backdrop to the coast. 20 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREA 1: UCHELDIR Y GOGLEDD KEY CHARACTERISTICS OF THE LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREA1 Dramatic and varied topography; rising up steeply from the Conwy coast Sychnant Pass SSSI, in the north-east of the LCA, comprising dry heath, acid at Penmaen-bach Point to form a series of mountains, peaking at Foel-Fras grassland, bracken, marshland, ponds and streams – providing a naturalistic backdrop (942 metres). Foothills drop down from the mountains to form a more to the nearby Conwy Estuary. intricate landscape to the east and west. Wealth of nationally important archaeological features including Bronze Age Complex, internationally renowned geological and geomorphological funerary and ritual monuments (e.g. standing stones at Bwlch y Ddeufaen), prominent landscape, with a mixture of igneous and sedimentary rocks shaped by Iron Age hillforts (e.g. Maes y Gaer and Dinas) and evidence of early settlement, field ancient earth movements and exposed and re-modelled by glaciation. systems and transport routes (e.g. -

Voluntary Warden Inform Ation Pack 2020 Snowdonia National Park

20 20 Pack Authority Park Information National Warden 1 Voluntary Snowdonia Content Important Contacts ................................................................................................................................. 3 DEALING WITH A MEDICAL EMERGENCY ON THE MOUNTAIN ............................................................... 3 Dealing with Difficult Behaviour .............................................................................................................. 5 Kit List ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Daily Schedule ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Routes up Snowdon ................................................................................................................................ 8 Llanberis Path......................................................................................................................... 8 PyG Track ............................................................................................................................. 11 Miners Track ........................................................................................................................ 14 Visitor FAQ’s .......................................................................................................................................... 17 Appendix 1 – Risk Assessments -

Voluntary W Arden Inform Ation Pack 2021 Snowdonia National Park

21 20 Pack Authority Park Information National Warden 1 Voluntary Snowdonia Content Important Contacts ................................................................................................................................. 3 DEALING WITH A MEDICAL EMERGENCY ON THE MOUNTAIN ............................................................... 3 Dealing with Difficult Behaviour .............................................................................................................. 5 Kit List ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Daily Schedule ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Routes up Snowdon ................................................................................................................................ 8 Llanberis Path......................................................................................................................... 8 PyG Track ............................................................................................................................. 11 Miners Track ........................................................................................................................ 14 Visitor FAQ’s .......................................................................................................................................... 17 Appendix 1 – Risk Assessments -

Gaeaf 2003Opens in a New Window

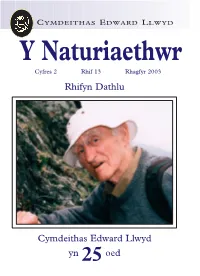

CYMDEITHAS EDWARD LLWYD Dosberthir yn rhad i aelodau Cymdeithas Edward Llwyd Pris i’r cyhoedd Rhifyn arbennig £3.50 Cyhoeddir Y Naturiaethwr yn rhannol trwy Y Naturiaethwr gymhorthdal gan Gyngor Cefn Gwlad Cymru Cyfres 2 Rhif 13 Rhagfyr 2003 Rhifyn Dathlu Cymdeithas Edward Llwyd yn 25 oed Lluniau’r Clawr Clawr blaen: Dafydd Dafis, Rhandirmwyn, Llywydd a sylfaenydd Cymdeithas Edward Llwyd, yn astudio Lili’r Wyddfa ar Glogwyn Du’r Arddu,Yr Wyddfa, Mai 2003 Llun: Ifor Williams Clawr ôl: Lili’r Wyddfa (neu Brwynddail y Mynydd) Lloydia serotina Llun: Goronwy Wynne Cymdeithas Edward Llwyd Sefydlwyd Cymdeithas Edward Llwyd yn 1978 a hi yw Cymdeithas Genedlaethol Naturiaethwyr Cymru. Enwir y Gymdeithas ar ôl Edward Llwyd, a anwyd yn 1660 ac a alwyd yn ei gyfnod “y naturiaethwr gorau yn awr yn Ewrop”. Cymraeg yw iaith y Gymdeithas, ac y mae dros 1,200 o aelodau led-led Cymru a thu hwnt. Prif ddibenion y Gymdeithas yw astudio byd natur, yn cynnwys planhigion, anifeiliaid a chreigiau, gan hyrwyddo ymwybyddiaeth o amgylchedd a threftadaeth naturiol Cymru ac ymgyrchu dros eu gwarchod. Mae’r Gymdeithas yn: • trefnu cyfarfodydd awyr-agored ym mhob rhan o Gymru, i astudio ac i gerdded • cynnal cyfarfodydd gwaith cadwriaethol • trefnu darlithoedd a chyfarfodydd cymdeithasol • cynnal pabell ar faes yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol • cyhoeddi Y Naturiaethwr ddwywaith y flwyddyn • cyhoeddi Cylchlythyr ddwywaith y flwyddyn • cyhoeddi llyfrau ar enwau Cymraeg creaduriaid a phlanhigion • cynnig grantiau (£600) bob blwyddyn am waith gwreiddiol ym myd natur • lleisio barn gyhoeddus ar faterion amgylcheddol • trefnu pris gostyngol gyda nifer o siopau dillad ac offer awyr agored Mae aelodaeth yn agored i bawb o bob oed sydd â diddordeb ym myd natur.