The Fifth Commandment and Translations of Other Short

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where's Brock?

• • ... , . Volume 30, Issue 8 Concordia College, 275 North Syndicate, St. Paul, MN 55104 Friday Febraury 17, 1995 Where's Brock? by Amy MacFee Why the resignation? John Brockopp replies, agreement with Concordia that he wouldn't have Department from being almost exclusively staffed "the policy [at Service Master] is to move manage- to leave if he took the supervisor position." In fact, by students (which did not work out) to being Everyone knew John Brockopp; he was the ment people after a certain number of years." But, he asked Chitty if he (Brockopp) would have to be staffed by part time employees. Chitty comment- Custodial Department Supervisor. Where has he Bob Zuniga, a custodian who worked under transferred, and Chitty responded, ("Brock' does ed, "John was key in training and scheduling and gone? Unfortunately, Brockopp resigned his posi- Brockopp, felt "he was forced to leave," and was a not have to move unless 'Brock' wants to move." getting that job done." Brock is remembered for tion and served his last day on February 10. He "victim of two long term problems in the depart- But, Brockopp did have to leave. Chitty explained, his hard work said Chitty: "It wouldn't be right to was offered a choice between four different man- ment: lack of money; and lack of man power." "Our intention was to have John in the [supervi- say he didn't give it everything he had." agerial positions, but he would have had to relo- However, John Chitty, head of the Custodial sor] position as long as he filled the position, but Brockopp assisted Zuniga in several of his cate upon acceptance of them. -

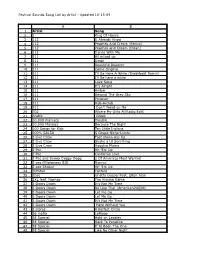

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Microbial Community and Geochemical Analyses of Trans-Trench Sediments for Understanding the Roles of Hadal Environments

The ISME Journal (2020) 14:740–756 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-019-0564-z ARTICLE Microbial community and geochemical analyses of trans-trench sediments for understanding the roles of hadal environments 1 2 3,4,9 2 2,10 2 Satoshi Hiraoka ● Miho Hirai ● Yohei Matsui ● Akiko Makabe ● Hiroaki Minegishi ● Miwako Tsuda ● 3 5 5,6 7 8 2 Juliarni ● Eugenio Rastelli ● Roberto Danovaro ● Cinzia Corinaldesi ● Tomo Kitahashi ● Eiji Tasumi ● 2 2 2 1 Manabu Nishizawa ● Ken Takai ● Hidetaka Nomaki ● Takuro Nunoura Received: 9 August 2019 / Revised: 20 November 2019 / Accepted: 28 November 2019 / Published online: 11 December 2019 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is published with open access Abstract Hadal trench bottom (>6000 m below sea level) sediments harbor higher microbial cell abundance compared with adjacent abyssal plain sediments. This is supported by the accumulation of sedimentary organic matter (OM), facilitated by trench topography. However, the distribution of benthic microbes in different trench systems has not been well explored yet. Here, we carried out small subunit ribosomal RNA gene tag sequencing for 92 sediment subsamples of seven abyssal and seven hadal sediment cores collected from three trench regions in the northwest Pacific Ocean: the Japan, Izu-Ogasawara, and fi 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: Mariana Trenches. Tag-sequencing analyses showed speci c distribution patterns of several phyla associated with oxygen and nitrate. The community structure was distinct between abyssal and hadal sediments, following geographic locations and factors represented by sediment depth. Co-occurrence network revealed six potential prokaryotic consortia that covaried across regions. Our results further support that the OM cycle is driven by hadal currents and/or rapid burial shapes microbial community structures at trench bottom sites, in addition to vertical deposition from the surface ocean. -

OCEANS ´09 IEEE Bremen

11-14 May Bremen Germany Final Program OCEANS ´09 IEEE Bremen Balancing technology with future needs May 11th – 14th 2009 in Bremen, Germany Contents Welcome from the General Chair 2 Welcome 3 Useful Adresses & Phone Numbers 4 Conference Information 6 Social Events 9 Tourism Information 10 Plenary Session 12 Tutorials 15 Technical Program 24 Student Poster Program 54 Exhibitor Booth List 57 Exhibitor Profiles 63 Exhibit Floor Plan 94 Congress Center Bremen 96 OCEANS ´09 IEEE Bremen 1 Welcome from the General Chair WELCOME FROM THE GENERAL CHAIR In the Earth system the ocean plays an important role through its intensive interactions with the atmosphere, cryo- sphere, lithosphere, and biosphere. Energy and material are continually exchanged at the interfaces between water and air, ice, rocks, and sediments. In addition to the physical and chemical processes, biological processes play a significant role. Vast areas of the ocean remain unexplored. Investigation of the surface ocean is carried out by satellites. All other observations and measurements have to be carried out in-situ using research vessels and spe- cial instruments. Ocean observation requires the use of special technologies such as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), towed camera systems etc. Seismic methods provide the foundation for mapping the bottom topography and sedimentary structures. We cordially welcome you to the international OCEANS ’09 conference and exhibition, to the world’s leading conference and exhibition in ocean science, engineering, technology and management. OCEANS conferences have become one of the largest professional meetings and expositions devoted to ocean sciences, technology, policy, engineering and education. -

3000 Unique Captions, Status, Quotes

3000 UNIQUE CAPTIONS, STATUS, QUOTES S I D D H A R T H Introduction Hey Guys! I am Siddharth. Here I have compiled 3000 unique Instagram captions, quotes, status just for you! The idea behind creating this e-book was the love I got from you all from past 2 years. So here is a small gesture in a way of saying thank you to all for loving us and our captions. I know the need of captions has risen so fast that people are not getting unique captions for their amazing posts. So that's why my friend, I have got you this amazing list of captions which you will never find anywhere on internet! And do you know what's the best part is? That this book is with you forever! You can literally post daily on your social media accounts for BACK-TO-BACK 3000 DAYS, which is actually 8 YEARS! That is INSANE, NO?? So, now that you have literally trashed your tension of what to post everyday, you can now chill, relax and select the best caption for next day! Table Of Contents 1.Life Inspirational Captions....................... Pg No. 01 2.Cool Attitude Captions............................. Pg No. 06 3.Love Captions............................................. Pg No. 08 4.Break-Up Quotes....................................... Pg No. 09 5.Captions For Friends................................. Pg No. 11 6.Motivational Captions............................... Pg No. 13 7.Good Morning Quotes.............................. Pg No. 14 8.Captions For Pictures................................ Pg No. 16 9.Selfie Captions............................................ Pg No. 19 10.Mirror Selfie Captions............................... Pg No. 24 11.Video Call Captions.................................. -

Dataposter SUMERGIBLES

TECNOLOGÍA DE LA 8 de junio EXPLORACIÓN MARINA DÍA MUNDIAL DE LOS OCÉANOS LOS EXPLORADORES LAS EXPLORADORAS HISTÓRICOS EN MÉXICO JAQUES VIVIANNE SOLÍS COUSTEAU WEISS (1910-1997) En 1985 se convirtió en la primera Ocial naval francés, explorador, investigadora en jefe de crucero investigador y biólogo marino en los buques de investigación interesado en el estudio del mar y PRESENTA "El Puma" y "Justo Sierra" de la la vida que alberga. Se le UNAM, los cuales también dirigió recuerda por haber presentado al en las expediciones de 1992 y mundo la escafandra autónoma 1993. Fue la primera cientíca con independencia de cables y latinoamericana a bordo del tubos de suministro de aire desde submarino Alvin, sumergiéndose la supercie. a más de 2000 metros de profundidad. JACQUES SUMERGIBLES ELVA ESCOBAR PICCARD BRIONES (1922-2008) Su línea de trabajo se centra en la Explorador, ingeniero y fauna asociada a los fondos oceanógrafo suizo, conocido por DE INVESTIGACIÓN marinos y en la macroecología de el desarrollo de vehículos los ambientes acuáticos. Ha subacuáticos para el estudio de descubierto nuevos ecosistemas las corrientes oceánicas. Piccard y La exploración de las profundidades marinas tiene por objetivo la investigación de las y descrito nuevas especies. Ha Don Walsh fueron, hasta 2012, las representado a México en temas únicas personas que alcanzaron condiciones físicas, químicas y biológicas del lecho marino con motivos científicos o comerciales. de conservación ante la el punto más bajo de la supercie Es una actividad relativamente reciente, pero ha resultado en grandes aportaciones al desarrollo Autoridad Internacional de los terrestre, el abismo Challenger, Fondos Marinos, las Naciones en la fosa de las Marianas. -

A Liminal Experience Under the Surface of the Ocean

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES APNEA A liminal experience under the surface of the ocean Janna Nadjejda Ribow Guichet Dissertação Mestrado em Arte Multimedia Especialização em Fotografia Dissertação orientada pela Professora Doutora Maria João Pestana Noronha Gamito 2021 DECLARAÇÃO DE AUTORIA Eu Janna Nadjejda Ribow Guichet, declaro que a presente dissertação de mestrado intitulada “Apnéia”, é o resultado da minha investigação pessoal e independente. O conteúdo é original e todas as fontes consultadas estão devidamente mencionadas na bibliografia ou outras listagens de fontes documentais, tal como todas as citações diretas ou indiretas têm devida indicação ao longo do trabalho segundo as normas académicas. O Candidato [assinatura] Lisboa, 27.10.19 RESUMO O trabalho é sobre uma imersão no oceano e em nós mesmos. A questão é: como podemos obter um efeito positivo por meio do oceano? O primeiro capítulo analisará os pensamentos antigos e contemporâneos do sublime; A figura do vórtice foi usada nas artes e na literatura para criar sensações sublimes, Immanuel Kant e Edmund Burke afirmaram que o sublime pode trazer um efeito positivo que será discutido. Uma sensação sublime diferente é a Liminalidade, que encontrei durante a Apnéia. Muitos artistas descrevem seu poder transformador, que será comparado à pesquisa médica científica. Mas a mensagem fundamental permanece: “A experiência sublime é fundamentalmente transformadora, sobre a relação entre desordem e ordem, e a ruptura das coordenadas estáveis de tempo e espaço. Algo se precipita e somos profundamente alterados.” (Morley, 2010, p.12) O segundo capítulo define Ambientes Imersivos em Artes e Apnéia. Após a experiência liminar comecei a treinar o desporto e aprendi a controlar minha mente e corpo de forma imersiva, o que trouxe à tona os conceitos: ponto do silêncio (preparação), jogo mental (submersão) e foco (volta a superfície). -

Under High Pressure: Spherical Glass Flotation and Instrument Housings in Deep Ocean Research

PAPER Under High Pressure: Spherical Glass Flotation and Instrument Housings in Deep Ocean Research AUTHORS ABSTRACT Steffen Pausch All stationary and autonomous instrumentation for observational activities in Nautilus Marine Service GmbH ocean research have two things in common, they need pressure-resistant housings Detlef Below and buoyancy to bring instruments safely back to the surface. The use of glass DURAN Group GmbH spheres is attractive in many ways. Glass qualities such as the immense strength– weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and low cost make glass spheres ideal for both Kevin Hardy flotation and instrument housings. On the other hand, glass is brittle and hence DeepSea Power & Light subject to damage from impact. The production of glass spheres therefore requires high-quality raw material, advanced manufacturing technology and expertise in Introduction processing. VITROVEX® spheres made of DURAN® borosilicate glass 3.3 are the hen Jacques Piccard and Don only commercially available 17-inch glass spheres with operational ratings to full Walsh reached the Marianas Trench ocean trench depth. They provide a low-cost option for specialized flotation and W instrument housings. in1960andreportedshrimpand flounder-like fish, it was proven that Keywords: Buoyancy, Flotation, Instrument housings, Pressure, Spheres, Trench, there is life even in the very deepest VITROVEX® parts of the ocean. What started as a simple search for life has become over (1) they need to have pressure- the years a search for answers to basic Advantages and resistant housings to accommodate questions such as the number of spe- Disadvantages sensitive electronics, and (2) they need cies, their distribution ranges, and the of Glass Spheres either positive buoyancy to bring the composition of the fauna. -

Comparative Perspectives on the Rise of the Brazilian Novel COMPARATIVE LITERATURE and CULTURE

Comparative Perspectives on the Rise of the Brazilian Novel COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND CULTURE Series Editors TIMOTHY MATHEWS AND FLORIAN MUSSGNUG Comparative Literature and Culture explores new creative and critical perspectives on literature, art and culture. Contributions offer a comparative, cross- cultural and interdisciplinary focus, showcasing exploratory research in literary and cultural theory and history, material and visual cultures, and reception studies. The series is also interested in language-based research, particularly the changing role of national and minority languages and cultures, and includes within its publications the annual proceedings of the ‘Hermes Consortium for Literary and Cultural Studies’. Timothy Mathews is Emeritus Professor of French and Comparative Criticism, UCL. Florian Mussgnug is Reader in Italian and Comparative Literature, UCL. Comparative Perspectives on the Rise of the Brazilian Novel Edited by Ana Cláudia Suriani da Silva and Sandra Guardini Vasconcelos First published in 2020 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Collection © Editors, 2020 Text © Contributors, 2020 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0). This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). -

Sabbath Sentinel September–October 2009 Volume 61, No

SabbathThe Sentinel September–October 2009 What are her religious rights in public school? BSA — The Bible Sabbath Association Jesus said, “the Son of Man is Lord also of the Sabbath” The Sabbath Sentinel September–October 2009 Volume 61, No. 5 Issue 539 FEATURES The Sabbath Sentinel is published bimonthly by The Bible Sabbath Association, 802 N. W. 21st Ave., Battle Ground, WA 98604. Copyright 4 Last Man Standing © 2009, by The Bible Sabbath Association. Printed in the U.S.A. All by Kenneth Westby rights reserved. Reproduction in any form without written permission is prohibited. Nonprofit bulk rate postage paid at Rapid City, South 6 First Steps to Revitalizing your Marriage Dakota. Editor: Kenneth Ryland, [email protected]. by Pastor David Guerrero Associate Editors: Julia Benson & Shirley Nickels 8 ALL the Commandments BSA’s Board of Directors for 2007-2011: by Greg Sereda President: John Paul Howell, [email protected] Vice President: Marsha Basner 11 I Can, but Will I? Vice President: June Narber by Bryant Buck Treasurer: Bryan Burrell Secretary: Calvin Burrell 12 The Divine Subjectivity Office Manager—Battle Ground, WA, Office: Shirley Nickels by Terril D. Littrell, Ph. D. Directors At Large: Darrell Estep, Calvin Burrell, Bryan Burrell, Rico Cortes, John Guffey, Dusti Howell, Tom Justus, Earl Lewis, Kenneth 16 Is Obedience a Condition of Salvation Ryland by Marvin Moore Subscriptions: Call (888) 687-5191 or write to: The Bible Sabbath Association, 802 N. W. 21st Ave., Battle Ground, WA 98604 or contact 20 Putting Faith in God First, us at the office nearest you (see international addresses below). -

Leslie Silko E James Redfield, Mentores De Uma Nova Consciência

Zaida Pinto Ferreira Leslie Silko e James Redfield, Mentores de uma Nova Consciência: da Fragmentação à Unidade Tese de Doutoramento em Literatura Especialidade em Literatura Norte-Americana UNIVERSIDADE ABERTA LISBOA 2013 Zaida Pinto Ferreira Leslie Silko e James Redfield, Mentores de uma Nova Consciência: da Fragmentação à Unidade Tese de Doutoramento apresentada à Universidade Aberta e realizada sob a orientação da Ex.ma Senhora Professora Doutora Maria Filipa Palma dos Reis UNIVERSIDADE ABERTA LISBOA 2013 A todos os Mestres que me inspiraram. Agradecimentos A elaboração desta dissertação de doutoramento contou com preciosos contributos que pretendo destacar. Assim, agradeço à Professora Doutora Filipa Palma dos Reis, minha orientadora, a disponibilidade, a dedicação, o apoio, e a leitura atenta e rigorosa que dedicou a este estudo, contribuindo para ampliar a minha visão sobre o tema. O seu empenho foi crucial para o resultado final deste trabalho. Expresso o meu agradecimento à Ana Maria Costa pelas preciosas sugestões que me facultou e pela leitura crítica, atenta e rigorosa que lhe mereceu o meu texto. Agradeço ainda às minhas amigas Anabela Sardo e Isa Severino pelo estímulo constante ao longo deste percurso, pelas ajudas que deram a este estudo, contribuindo para melhorar alguns aspectos. De igual modo, expresso o meu reconhecimento aos meus amigos que não preciso nomear, porque, de modo indirecto, concorreram para o sucesso do meu trabalho, com o seu apreço e amizade. Dedico uma mensagem especial aos meus filhos, Tiago, André, à minha mãe, ao meu irmão e à Mila, pois sem o saberem, deram-me um extremo alento para prosseguir esta travessia. -

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Plays Last Played Skips Last Ski ppedDancing MyQueen Rating ABBA LocationBenny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA For ever Gold I Rock 3715072 231 1 1 1 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 1Knowing Dancing me, Queen.mp3 knowing you ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA Forever Gold I Rock 3885158 241 1 1 2 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 2Take Knowing a chance me, knowingon me you.mp3 ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gol d I Rock 3924028 244 1 1 3 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file 2 9/10/11 10:56 PM Audio:ABBA:ABBA ForeverMamma mia Gold I:03 ABBA Take a Bennychance Andersson/Björn on me.mp3 Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA For ever Gold I Rock 3428328 213 1 1 4 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file 2 9/10/11 10:59 PM Audio:ABBA:ABBA ForeverLay all Goldyour I:04love Mammaon me mia.mp3 ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gol d I Rock 4401337 274 1 1 5 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 5Super Lay alltrouper your love ABBA on me.mp3 Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gold I Rock 4081599 254 1 1 6 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBAI