THE WAY WE SAY GOODBYE and OTHER STORIES a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where's Brock?

• • ... , . Volume 30, Issue 8 Concordia College, 275 North Syndicate, St. Paul, MN 55104 Friday Febraury 17, 1995 Where's Brock? by Amy MacFee Why the resignation? John Brockopp replies, agreement with Concordia that he wouldn't have Department from being almost exclusively staffed "the policy [at Service Master] is to move manage- to leave if he took the supervisor position." In fact, by students (which did not work out) to being Everyone knew John Brockopp; he was the ment people after a certain number of years." But, he asked Chitty if he (Brockopp) would have to be staffed by part time employees. Chitty comment- Custodial Department Supervisor. Where has he Bob Zuniga, a custodian who worked under transferred, and Chitty responded, ("Brock' does ed, "John was key in training and scheduling and gone? Unfortunately, Brockopp resigned his posi- Brockopp, felt "he was forced to leave," and was a not have to move unless 'Brock' wants to move." getting that job done." Brock is remembered for tion and served his last day on February 10. He "victim of two long term problems in the depart- But, Brockopp did have to leave. Chitty explained, his hard work said Chitty: "It wouldn't be right to was offered a choice between four different man- ment: lack of money; and lack of man power." "Our intention was to have John in the [supervi- say he didn't give it everything he had." agerial positions, but he would have had to relo- However, John Chitty, head of the Custodial sor] position as long as he filled the position, but Brockopp assisted Zuniga in several of his cate upon acceptance of them. -

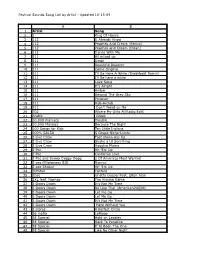

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Thesis-1949-S649l.Pdf (10.18Mb)

1 LEATHEBS EMPLOYED I ·l THE 'l'EAC I.NG OF LEA'll:iERCRAFT ii LEA'IDERS ff LOYED I THE 'l'E ' C I TG OF LEATHERCRAFT By HARRY LEE ..s -, ITH Bachelor of Science ort.h Texas State Teachers College Denton, Texas 1947 Submitted to the Department of Industrial Arts Education Oklahoma Agx-icultural and echenieal. College In Partial Fulfillment. of the Requirement.a For the Degree of TER OF SCIEJ'"CE 1949 iii 1iies1s .vis · r a · Head, School of Iniust.ria.l Arts Ed.ucation WX1 Engineering Shopwork 236 592 iv AC K.J.~O' LE.DGMEN'rs 'lhe writer expresses hi sincere appreciation to Dr. De itt Hunt,, Head of the Department.. of Iroustrial. Arts Fiiucation and Engineering Shopwork, Ok1ahoma Agricul.tural am · echanical College1 for his helpful assistance and guidance during the preparation and completion of thia study. Appreciation is extentled to nw wife, Eunice Blood mith, for her encouragement and help throughout the preparation of this study. V TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. PRELIMI STATEMENTS ••••••••• • •• • l Purpose oft.he Study ••••••••••••• l '.Ille Importance of the Study ••••••••• 2 Delimit.ations • •. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 Def'inition of Terms ............. 3 A Preview of Organization •••••••••• 4 II. HISTORICAL STUDY OF LET.HER • • •• • • •• • • 5 The Raw Material • • • • • ., • • • • • • • • • 5 'Ihe Evolution of Leather ••••••••••• 6 '!he Egyptian Leather • • • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Early .Arabian Leather • • • • • • • • • ••• 7 The Jewish Babylonian Leather •••••••• 8 Gl"ec ian Leatber • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 8 Roman Leather • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 9 European Leather of the Middle Ages •••• • 9 Leather of the Far East • • • • • • • • • • • ll American Leather ••••••••••••••• 11 III. PRI CIPAL TYPES OF LEATHERCRAFT TERIALS • • • 14 Alligator • • • • • • • • • • • • • ••• .•• 14 Cabretta • • • • • • • • • • . -

3000 Unique Captions, Status, Quotes

3000 UNIQUE CAPTIONS, STATUS, QUOTES S I D D H A R T H Introduction Hey Guys! I am Siddharth. Here I have compiled 3000 unique Instagram captions, quotes, status just for you! The idea behind creating this e-book was the love I got from you all from past 2 years. So here is a small gesture in a way of saying thank you to all for loving us and our captions. I know the need of captions has risen so fast that people are not getting unique captions for their amazing posts. So that's why my friend, I have got you this amazing list of captions which you will never find anywhere on internet! And do you know what's the best part is? That this book is with you forever! You can literally post daily on your social media accounts for BACK-TO-BACK 3000 DAYS, which is actually 8 YEARS! That is INSANE, NO?? So, now that you have literally trashed your tension of what to post everyday, you can now chill, relax and select the best caption for next day! Table Of Contents 1.Life Inspirational Captions....................... Pg No. 01 2.Cool Attitude Captions............................. Pg No. 06 3.Love Captions............................................. Pg No. 08 4.Break-Up Quotes....................................... Pg No. 09 5.Captions For Friends................................. Pg No. 11 6.Motivational Captions............................... Pg No. 13 7.Good Morning Quotes.............................. Pg No. 14 8.Captions For Pictures................................ Pg No. 16 9.Selfie Captions............................................ Pg No. 19 10.Mirror Selfie Captions............................... Pg No. 24 11.Video Call Captions.................................. -

Saturday Faith Community News

Wildcat RELIGION tennis action Saturday Faith community news ...................................Page 3 .............Page 6 March 17, 2007 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Sunday: Clouds followed by sunshine 7 58551 69301 0 Monday: Afternoon rain 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 14 pages, Volume 148 Number 342 email: [email protected] Vet meds MOVING DAY FOR CALFIRE UKIAH UNIFIED stolen in Charter nighttime burglary school By KATIE MINTZ The Daily Journal If you love your pet, don’t buy flea, tick and heartworm products petition peddled on the street, said Dr. Kerry Levin, a veterinarian at North State Animal Hospital. The medicine, she said, could be part of the approximate $7,000 in denied loot a thief or thieves made away By LAURA MCCUTCHEON with from her clinic at 2280 N. The Daily Journal State St. sometime Thursday night. The Ukiah Unified School District has Levin said that when her assis- denied Charter Academy of the Redwoods’ tant showed up Friday morning to petition for the Career Academy of Ukiah open shop, he found a large rock because it needed more development, had been thrown through a win- specifically in the proposed educational dow and the hospital had been bur- program, said Dolores Fisette, administra- glarized. tive consultant with Ukiah Unified. “I would think they’d be look- “The concept was good; it just was too ing for money and drugs. I’m sur- Isaac Eckel/The Daily Journal general,” she said. “The petition is the prised they took medicine that is The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection has now moved into its major document for a charter school. -

FALL / WINTER 2017/2018 2017. Is It Fall and Winter?

THE FASHION GROUP FOUNDATION PRESENTS FALL / WINTER 2017/2018 TREND OVERVIEW BY MARYLOU LUTHER N E W Y O R K • LONDON • MILAN • PARIS DOLCE & GABBANA 2017. Is it Fall and Winter? Now and Next? Or a fluid season of see it/buy it and see it/wait for it? The key word is fluid, as in… Gender Fluid. As more women lead the same business lives as men, the more the clothes for those shared needs become less sex-specific. Raf Simons of Calvin Klein and Anna Sui showed men and women in identical outfits. For the first time, significant numbers of male models shared the runways with female models. Some designers showed menswear separately from women’s wear but sequentially at the same site. Transgender Fluid. Marc Jacobs and Proenza Schouler hired transgender models. Transsexuals also modeled in London, Milan and Paris. On the runways, diversity is the meme of the season. Model selections are more inclusive—not only gender fluid, but also age fluid, race fluid, size fluid, religion fluid. And Location Fluid. Philipp Plein leaves Milan for New York. Rodarte’s Kate and Laura Mulleavy leave New York for Paris. Tommy Hilfiger, Rebecca Minkoff and Rachel Comey leave New York for Los Angeles. Tom Ford returns to New York from London and Los Angeles. Given all this fluidity, you could say: This is Fashion’s Watershed Moment. The moment of Woman as Warrior—armed and ready for the battlefield. Woman in Control of Her Body—to reveal, as in the peekaboobs by Anthony Vaccarello for Yves Saint Laurent. -

Rules and Regulations

GOLD COAST GALLERIA CONDOMINIUM ASSOCIATION RULES AND REGULATIONS As Amended and Adopted August 5, 2015 r TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Pg. 3 Exterminating Pg. 28 Building Access “ Fire Extinguishers and Smoke Detectors Pg. 29 Basic Entry Procedures “ Plumbing Facilities “ Deliveries, Guests, and Service Access “ Ventilation “ Guests and Non-Residents Pg. 5 Waste Disposal “ Keys, Locks, Security Systems, Lockouts “ Window Washing Pg. 30 Elevators Pg. 6 Emergency Procedures Pg. 31 Security Pg. 7 Emergency Numbers “ Solicitation “ Fire Safety “ Common Elements-Use & Restrictions “ Ambulances “ Advertisements, Communications, and Solicitations Pg, 8 Water Emergencies/Leaks “ Balconies “ Damages to Personal or Common Property/Insurance Pg. 32 Bicycles, Tricycles, Rollerblades Pg. 9 Enforcement Pg. 33 Exterior Appearance and Attachments “ Rule Violation Enforcement “ HVAC Pg, 10 Fines “ Lobby Appearance “ Rules Regarding Elections Pg. 34 Hallways, Stairwells, and Lobby “ Nominations of Candidates “ Mail Pg. 11 Qualifications “ Parking “ Election Inspectors “ Unit Occupancy-Use & Restrictions “ Election & Tabulation of Ballots “ General Use and Restrictions “ Results of Election “ Interior Appearance Pg. 12 Campaign Rules “ Construction and Remodeling “ Conclusion Pg. 35 Drain Cleaners Pg. 13 Useful Telephone Numbers “ Employees of Residents “ Index Pg. 36 Jacuzzi/Hot Tubs “ Musical Instruments “ Noise/ Nuisances “ Washers and Dryers Pg. 14 Water Furniture “ Windows “ Pets “ General Restrictions and Pet Registration Pg. 15 Visiting Pets Pg.17 Amenities “ Sundeck “ Cable/Satellite Television Pg.18 Laundry Room “ Luggage Carts “ Assessments & Collections Pg.19 Monthly Statements “ Due Date & Late Fee “ Non-Sufficient Funds Check “ Collection of Past Due Accounts “ Sales, Leasing & Refinancing Procedures Pg.20 Sales of Units “ Mortgage Disclosure Forms & Refinancing “ Leases and Owner Responsibility Pg. 21 Open House, Estate Sales, and Auctions Pg. -

Fashionpedia: Ontology, Segmentation, and an Attribute Localization Dataset

Fashionpedia: Ontology, Segmentation, and an Attribute Localization Dataset Menglin Jia?1, Mengyun Shi?1;4, Mikhail Sirotenko?3, Yin Cui?3, Claire Cardie1, Bharath Hariharan1, Hartwig Adam3, Serge Belongie1;2 1Cornell University 2Cornell Tech 3Google Research 4Hearst Magazines Abstract. In this work we explore the task of instance segmentation with attribute localization, which unifies instance segmentation (detect and segment each object instance) and fine-grained visual attribute cat- egorization (recognize one or multiple attributes). The proposed task requires both localizing an object and describing its properties. To illus- trate the various aspects of this task, we focus on the domain of fashion and introduce Fashionpedia as a step toward mapping out the visual aspects of the fashion world. Fashionpedia consists of two parts: (1) an ontology built by fashion experts containing 27 main apparel categories, 19 apparel parts, 294 fine-grained attributes and their relationships; (2) a dataset with everyday and celebrity event fashion images annotated with segmentation masks and their associated per-mask fine-grained at- tributes, built upon the Fashionpedia ontology. In order to solve this challenging task, we propose a novel Attribute-Mask R-CNN model to jointly perform instance segmentation and localized attribute recogni- tion, and provide a novel evaluation metric for the task. Fashionpedia is available at: https://fashionpedia.github.io/home/. Keywords: Dataset, Ontology, Instance Segmentation, Fine-Grained, Attribute, Fashion 1 Introduction Recent progress in the field of computer vision has advanced machines' ability to recognize and understand our visual world, showing significant impacts in arXiv:2004.12276v2 [cs.CV] 18 Jul 2020 fields including autonomous driving [52], product recognition [32,14], etc. -

BC CATALOGO AI1920 ENG.Pdf

Fall Winter Collection 2019/2020 2 The Time for the Spirit and Harmony THE TIME FOR THE pirit and Harmony The time in which heart and mind, free from everyday troubles, come back together in the deepest essence of our being human is time for the Spirit. We can find that time wherever we want it. Like when we leave our workplace in the evening, and when we close the door we also leave behind us what’s necessary in life: that’s time for the spirit. IIIIII “Time transforms nd if we go home tower, get a bit closer to the stars, things, on foot, we might and feel the beauty of the time that in just raise our eyes that enchanted place we’ll dedicate to just as skywards. Of course, the spirit and its mysterious meaning, this is more likely spending hours regenerating and in dreams” to happen if we’re reflecting in solitude. Time transforms lucky enough to live in the countryside, things, just as in dreams, and there is no whereA everything is gentler, calmer, apparent reason to it. How beautiful are more peaceful, more profound. And then all those things that can be understood we’ll see the twinkling lights of the stars, without needing to be explained by and it will seem as if we understood reason! When we take time for the the silent language of the celestial spirit, we see new, profound things, vault. We will read in it the mystery of and old things from a new perspective: time for spirit and that of the universal where once we felt sorrow, we now infinite. -

Table of Contents

Table Of Contents Early Days of Rogers, Family 1 Rogers Calf Skin Heads 7 The Covington Era 9 Henry Grossman 12 Joe Thompson 13 Grossman Buys Rogers 19 Ben Strauss 20 Covington Factory Building 24 Rogers Personnel, Covington Era 26 George Way and Rogers 32 Roland “Peewee” Davidson 34 English Rogers 35 Arbiter Autotune Drums 38 Grossman sells Rogers to CBS 40 Covington Fire of 1967 41 CBS Moves Rogers From Covington 42 CBS-Era Rogers 43 Memriloc Hardware 46 Rogers Rack System 47 Rogers Snare Machine 48 R&D Projects, 1980s 53 Craig Krampf 54 Rogers Factory Moves 1952–1984 56 Roy Burns 57 Dave Gordon and John Cermenaro 61 Post-CBS Rogers 64 Rogers Endorsees 65 Craig Krampf 79 Dating interview with Bobby Chiasson 84 Rogers Catalogs 85 Colors 89 Steve Maxwell Collection 95 Gary Nelson Collection 97 Bruce Felter Collection 99 Ray Bungay collection 101 Bobby Chiasson Rogers photos 102 Brook Mays Music Rogers 107 Dating Guide Shells 117 Lugs 119 Strainers 123 Spurs 126 Badges 127 Bass Drum Logos 129 Cymbal Stands 131 High Hat Stands 134 Snare Stands 137 Pedals 140 Tom Holders 143 Hoops 148 Snare Drums 149 Outfts 157 Malletron 172 Timpani 173 Budget, Import Outfts 176 Dyna-Sonic Snare Drum 179 Skinny Drum 195 Swivomatic Hardware 197 Parts 198 Index 225 Rogers resources today 227 Early Days of Rogers Joseph H. Rogers learned Son, Bacon, and dozens of others. Rogers heads were his trade as a boy in the not the cheapest, but were without question the fnest. parchment yards of Dublin, Even drum companies that eventually opened their own Ireland. -

Lookbook About O’Connors

Fall & Winter 2016 LOOKBOOK ABOUT O’CONNORS UPDATED CLASSICS AND CONTEMPORARY STYLES O’Connors is synonymous with both. Fifty years on and we’re still proud to help people put their best foot forward. We feature the finest and hottest labels and collections from around the world. Our tailor shop is unsurpassed in Canada, expertly accommodating your rush fittings. O’Connors shoe stores offer, simply put, the largest selection of men’s fine footwear available in Canada. Our extensive inventory of sizes and widths means we are certain to have what you are looking for. Experience superlative service and unique collections at O’Connors Women’s store. From business to denim — and beyond — we offer an extensive selection of clothing, fantastic footwear and accessories. Our on-site tailor will guarantee you’ll look your best. O’Connors continues to bring cutting edge fashion and new trends to Calgary. We strive to surpass your every need. Owner operated and proudly local, discover for yourself what discerning Calgarians have known for more than half a century – O’Connors is an unparalleled one-stop shopping experience. SERGEI POLUNIN, BALLET DANCER PALZILERI.COM <No intersecting link> 4 • Topcoat $1198 • Check Suit $898 • Shirt $178 • Tie $128 • Belt $108 • Scarf $118 RON WHITE Top to Bottom Easton in Cognac, Navy and Black $445 5 • Goose Down Quilted Coat $1198 • Quarter Zip Nautical Sweater $528 • Shirt $278 Top to Bottom ALLEN EDMONDS: 6 • BRAX Micro-Wool Casual Trouser $228 • ALLEN EDMONDS Belt $140 • ECCO Boot Roxton $320 • Alumnus Brown -

Mail on Sunday Reveals 999 Operators Are Ordering the Public To

Cookie Policy Feedback Monday, Mar 19th 2018 12AM -1°C 3AM -1°C 5-Day Forecast Home News U.S. Sport TV&Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Fashion Finder Latest Headlines Health Health Directory Discounts Login 'Why won't they let the dead rest?' Mail Site Web Enter your search on Sunday reveals 999 operators are Advertisement ordering the public to resuscitate the dead bodies of loved ones who can't be saved for fear of 'getting in trouble' Call staff routinely ordering grieving relatives to perform CPR on dead bodies Families being 'guilt tripped' by handlers who say they'll get into trouble Doctors now demanding urgent overhaul of 999 services following MoS exposé By LOIS ROGERS FOR THE MAIL ON SUNDAY PUBLISHED: 22:00, 23 September 2017 | UPDATED: 00:00, 24 September 2017 233 257 shares View comments Emergency call handlers are routinely issuing ‘grotesque’ instructions ordering callers to attempt to resuscitate the bodies of loved ones who are obviously beyond help, The Mail on Sunday can reveal. In horrific accounts given to this newspaper, readers have told how they were commanded to perform futile chest compressions on corpses already blackened with decomposition, stiff with rigor mortis or badly damaged. Like +1 Daily Mail Daily Mail Some told how operators ‘shouted’ at Follow Follow them, despite protestations that a @DailyMail Daily Mail parent, spouse or other family member Follow Follow had ‘been dead for hours’. @MailOnline Daily Mail Others were told they would ‘get into DON'T MISS trouble’ if they did not comply with EXCLUSIVE: Ant instructions, and they spoke of how they McPartlin emerges from were made to feel ‘guilty’ for not doing the wreck of his £26,000 Mini - SECONDS after Mini - SECONDS after enough if they objected to carrying out crashing' as Saturday CPR attempts.