Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis-1949-S649l.Pdf (10.18Mb)

1 LEATHEBS EMPLOYED I ·l THE 'l'EAC I.NG OF LEA'll:iERCRAFT ii LEA'IDERS ff LOYED I THE 'l'E ' C I TG OF LEATHERCRAFT By HARRY LEE ..s -, ITH Bachelor of Science ort.h Texas State Teachers College Denton, Texas 1947 Submitted to the Department of Industrial Arts Education Oklahoma Agx-icultural and echenieal. College In Partial Fulfillment. of the Requirement.a For the Degree of TER OF SCIEJ'"CE 1949 iii 1iies1s .vis · r a · Head, School of Iniust.ria.l Arts Ed.ucation WX1 Engineering Shopwork 236 592 iv AC K.J.~O' LE.DGMEN'rs 'lhe writer expresses hi sincere appreciation to Dr. De itt Hunt,, Head of the Department.. of Iroustrial. Arts Fiiucation and Engineering Shopwork, Ok1ahoma Agricul.tural am · echanical College1 for his helpful assistance and guidance during the preparation and completion of thia study. Appreciation is extentled to nw wife, Eunice Blood mith, for her encouragement and help throughout the preparation of this study. V TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. PRELIMI STATEMENTS ••••••••• • •• • l Purpose oft.he Study ••••••••••••• l '.Ille Importance of the Study ••••••••• 2 Delimit.ations • •. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 Def'inition of Terms ............. 3 A Preview of Organization •••••••••• 4 II. HISTORICAL STUDY OF LET.HER • • •• • • •• • • 5 The Raw Material • • • • • ., • • • • • • • • • 5 'Ihe Evolution of Leather ••••••••••• 6 '!he Egyptian Leather • • • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Early .Arabian Leather • • • • • • • • • ••• 7 The Jewish Babylonian Leather •••••••• 8 Gl"ec ian Leatber • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 8 Roman Leather • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 9 European Leather of the Middle Ages •••• • 9 Leather of the Far East • • • • • • • • • • • ll American Leather ••••••••••••••• 11 III. PRI CIPAL TYPES OF LEATHERCRAFT TERIALS • • • 14 Alligator • • • • • • • • • • • • • ••• .•• 14 Cabretta • • • • • • • • • • . -

Alden Shoe Company

Est. 1884 Alden Shoe Company 1 Taunton Street Middleborough, MA 02346 508-947-3926 Fax 508-947-7753 www.AldenShoe.com The Alden Shoe Company has manufactured quality shoes for men since 1884. With over 130 years of unwavering dedication to the highest standards of shoe-making, we proudly offer our collection of American handcrafted footwear. Not redone yearly at the drawing board, but reaffirmed continuously in the shop, heavy with the scent of rich leathers carefully worked to offer the best. The original tassel moccasin. Often copied... never equalled. Tassel Moccasins Shell Cordovan Calfskin Suede Q 563 Color 8 Cordovan 561 Dark Brown Calfskin 666 Mocha Kid Suede 664 Black Cordovan 660 Black Calfskin Q 3403 Snuff Suede Q 662 Burnished Tan Calfskin Aberdeen Last 663 Burgundy Calfskin Aberdeen Last Single oak leather outsoles Single oak leather outsoles Aberdeen Last C 8-13 Single oak B 8-13 D 6-13 leather outsoles Additional sizes C 7-13 E 6-13 for 660: D 6-13 B 8-13 AA 8 1/2-14 E 6-13 C 7-13 A 8 1/2-14 EEE 6-12 D 6-13 B 14, 15 E 6-13 C 14, 15 EEE 6-12 D 14, 15 E 14 EE 6-13 EEE 13 EEEE 7-12 3 Using the centuries-old method of pure vegetable tanning and hand finishing, the single tannery still producing genuine shell cordovan today is indeed practicing a rare art. The tanning process takes a full six months to complete and produces leather that is soft and supple, yet very durable.. -

Shoe and Leather Encyclopedia;

TS 945 .S35 - Copy 1 Shoe "d Leather Encyclopedia ISSUED BY THE SHOE AND LEATHER GAZETTE SAINT LOUIS Shoes of Quality As a business man you know that a factory with a large output can produce an article of manufacture at less cost than can a factory with a small output. Therein lies the explanation of the unusual quality in American Lady and American Gentleman Shoes. They are made by the largest makers of shoes in the world. Their enormous purchases insure the best quality of materials at the lowest price. They get the best workmen—can employ the best designers—their selling expense must be less per shoe. All of this result in but one thing—the best shoes for the money. You get the benefit. The H B Idea "KEEP THE QUALITY UP " St. Louis m&k r Jb MB Boston Shoexo- TRADE MARK All Leather Shoes In all lines of shoes for men, women and children, the "All Leather" line brings the best results for the merchant :: :: Senate and Atlantic SHOES FOR MEN Pacific and Swell SHOES FOR WOMEN Red Goose School Shoes FOR BOYS AND GIRLS CATALOG ON REQUEST Friedman-Shelby Shoe Co. 1625 Washington Ave. - - ST. LOUIS COPYRIGHT 1911 TRADESMEN'S PUBLISHING CO. ©CI.A292164 SHOE and LEATHER ENCYCLOPEDIA A Book of Practical and Expert Testimony by Successful Merchants Each A rticle a Chapter Each Chapter a Single and Separate Subject PUBLISHED BY THE SHOE AND LEATHER GAZETTE SAINT LOUIS - ' ..-— - " " mm i n i ~ T The Nine O'Clock^ School Shoe Dealer is IS A Public Benefactor As He Aids in the Distribution of Free Flags to Schools Read all about this fascinating trade attraction in our special "Nine O'clock" Catalog. -

Product Care Instructions

PRODUCT CARE INSTRUCTIONS TEXTILES Care for textiles by vacuuming or lightly brushing. Rotate and flip cushions when vacuuming for even wear. Keeping textiles away from direct sunlight. The nap of high pile textiles (mohairs & velvets) may become crushed or lose its original pile height. We recommend light steaming to lift the pile to its original height. The textile should also be brushed with a de-linting brush to maintain its pile. Water based or solvent cleaner may cause discoloration or staining. We recommend that stained or soiled textiles be professionally cleaned. LEATHERS Leather is a soft porous material that is sometimes uncoated. It can easily absorb liquids and oily substances. Avoid saturating the leather with lotion or water. Care by dusting and lightly vacuuming. Keep leathers away from direct sunlight and heating vents. Leathers are a natural, “living” material that breathe and move as they wear. We recommend that stained or soiled leathers be professionally cleaned. VELLUM Vellum is a natural parchment produced from calfskin, lambskin, or kidskin. As it is a skin, there are naturally occurring variations in pattern, color, and texture, which may be noticeable in side by side panels. A clear coat of sealant is added to protect the vellum. Care for vellum by wiping gently with a damp to dry soft cloth, making sure that the skin is completely dried. Keeping vellum away from direct sunlight and heating vents. Vellum is a natural, “living” material and breathes and moves as it wears Vellum may also darken over time. We recommend that stained or soiled vellum be professionally cleaned. -

BC CATALOGO AI1920 ENG.Pdf

Fall Winter Collection 2019/2020 2 The Time for the Spirit and Harmony THE TIME FOR THE pirit and Harmony The time in which heart and mind, free from everyday troubles, come back together in the deepest essence of our being human is time for the Spirit. We can find that time wherever we want it. Like when we leave our workplace in the evening, and when we close the door we also leave behind us what’s necessary in life: that’s time for the spirit. IIIIII “Time transforms nd if we go home tower, get a bit closer to the stars, things, on foot, we might and feel the beauty of the time that in just raise our eyes that enchanted place we’ll dedicate to just as skywards. Of course, the spirit and its mysterious meaning, this is more likely spending hours regenerating and in dreams” to happen if we’re reflecting in solitude. Time transforms lucky enough to live in the countryside, things, just as in dreams, and there is no whereA everything is gentler, calmer, apparent reason to it. How beautiful are more peaceful, more profound. And then all those things that can be understood we’ll see the twinkling lights of the stars, without needing to be explained by and it will seem as if we understood reason! When we take time for the the silent language of the celestial spirit, we see new, profound things, vault. We will read in it the mystery of and old things from a new perspective: time for spirit and that of the universal where once we felt sorrow, we now infinite. -

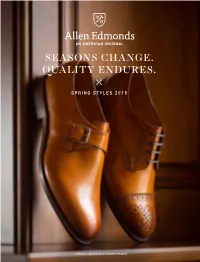

Seasons Change. Quality Endures

SEASONS CHANGE. QUALITY ENDURES. SPRING STYLES 2015 WARWICK AND ROGUE IN WALNUT (PAGE 8) HANDCRAFTED SPRING HAS SPRUNG A LEGACY WORTH CARRYING ON Artic blast. Polar vortex. Snowmageddon—winter these days feels more like a horror movie or disaster flick than a season. But your reward for the cold temps, icy winds and record snowfall is here: our Spring catalog featuring our latest designs perfect for the new year and the new you. With the weather transitioning from cold to warm you need to be prepared for anything. That means having a pair of our shoes with an all-weather Dainite sole. Made of rubber and studded for extra grip without the extra grime that comes with ridging, these soles let you navigate April showers without breaking your stride. Speaking of breaks, spring is a great time for one. If you are out on the open road or hopping on a plane, the styles in our Drivers Collection are comfortable and convenient travel footwear. Available in a variety of designs and colors, there is one For nearly a century we have (or more) to match your destination as well as your personality. PAGE 33 PAGE 14 continued to adhere to our 212-step manufacturing process Enjoy the Spring catalog and the sunnier days ahead. because great craftsmanship cannot and should not be Warm regards, rushed. To that end, during upper sewing, our skilled cutters and sewers still create the upper portion of each shoe by hand using time-tested methods, hand-cut pieces of leather PAUL GRANGAARD and dependable, decades-old President and CEO sewing machines. -

MINIATURE DESIGNER BINDINGS the Neale M

The Neale M. Albert Collection of MINIATURE DESIGNER BINDINGS The Neale M. Albert Collection of MINIATURE DESIGNER KLBINDINGS — , Photographs by Tom Grill / • KLCONTENTS Frontispiece: Neale M. Albert, , silver gelatin photograph by Patricia Juvelis by Lee Friedlander Some Thoughts on the Neale M. Albert Collection of Miniature Designer Bindings and the Grolier Club Traditions Copyright © by Piccolo Press/NY by Neale M. Albert All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from Piccolo Press/NY. --- Printed and bound in China ABOUT MINIATUREKL DESIGNER BINDINGS Some Thoughts on the Neale Albert Collection of Contemporary Designer Bindings and the Grolier Club Traditions a tradition that started in , with two exhibitions of fine bindings, the not be called a “contemporary” binding exhibition. In there was another I Grolier Club honors its namesake, the sixteenth century bibliophile and contemporary American binding exhibition, “Contemporary American patron of book binders, Jean Grolier, vicomte d’Aguisy. Jean Grolier’s collec- Hand Bindings.” In , the Grolier embarked on the first of a continuing tion of fine bindings, commissioned by him from binders working in his day, is series of collaborative exhibitions with the Guild of Book Workers on the still a benchmark for collectors of contemporary bindings. Since its founding in occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of that group’s founding. In , an exhi- , and continuing with this exhibition of Neale Albert’s collection of con- bition of contemporary English book bindings was organized. In “The temporary designer bindings on miniature books, the Grolier Club has mount- th Anniversary of the Guild of Book Workers,” and in , “Finely ed over exhibitions of finely bound books. -

Catalogo Generale 2015-Min.Pdf

03 INDEX The Company 05 Linea SG Natù® Line 06 SG Touch 11 Boots from Nappa calfskin 12 Boots from Full Grain calfskin 18 Boots SG Young Line 22 Gaiters 27 Jodhpur 32 SG Ultratech 36 SG Top 37 SG with crystals from Swarovski® 40 Accessories 49 05 Expressing talent is my passion. My first prototype saw the light of day over thirty years ago. It was the result of pure passion: for elegance, quality, innovation and the world of horse-riding – your world, your passion. With the help of expert staff, and listening to the needs of riders, I have always attempted to combine the great tradition and quality of Italian footwear with a search for perfect technical performance. And I have done so with the use of the most advanced technologies, while never betraying our values and ideals of hand-craftsmanship in every stage of production. This is the secret behind the creation of unique, original boots that satisfy the desires of each customer, be they enthusiasts or professional riders. By all means ask me for perfection – I will not be content until I have achieved it. Creating riding boots that are always better than the ones before is a constant challenge, an authentic contest in which what is at stake is the very concept of excellence. And this can be achieved only when the passion is authentic. SG Natù® line. Quality, beyond all limits. Only nubuck leather, with finishes in Full Grain calfskin: comfort, impermeability and sporting elegance, relinquishing nothing, not even during leisure time. The best of innovation, thanks to exclusive Natù® Technology. -

A L D E N N E W E N G L a N D E S T a B L I S H E D 1 8

Alden New England Established 1884 The Alden Shoe Company has manufactured quality shoes for men since 1884. With over 125 years of unwavering dedication to the highest standards of shoe-making, we proudly offer our collection of American handcrafted footwear. Not redone yearly at the drawing board, but reaffirmed continuously in the shop, heavy with the scent of rich leathers carefully worked to offer the best. Standards of Quality 1. Genuine Goodyear welt construction. 5. Every Alden New England shoe Top quality leather welting is securely carries a tempered steel shank, precisely stitched through the upper to the insole contoured and triple ribbed for extra rib. On models requiring the clean strength. Truly the backbone of a fine appearance of a close heel trim the welt shoe, the shank provides the welt runs from the heel forward. For proper support and shape so necessary other styles, such as brogues, where when your day involves walking and the solid look of an extended heel trim 1 time on your feet. is appropriate the welt is stitched all 6 around the shoe. 5 2 6. Oak tanned leather bends are cut 7 into outsoles at our factory for maximum 2. Long wearing rubber dovetail control of quality. heels with leather inserts. Solid brass 8 slugging gives secure attachment yet allows for easy rebuilding. 7. Every Alden New England shoe has a leather lining chosen from our special stock of supple glove linings and 3. Upper leather selected from the smooth, glazed linings. top grades of the finest tanneries in the world. Rich, aniline calfskins, luxurious 3 calf and kid suedes, and genuine shell cordovan. -

![IS 1640 (2007): Glossary of Terms Relating to Hides, Skins and Leather [CHD 17: Leather, Tanning Materials and Allied Products]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7197/is-1640-2007-glossary-of-terms-relating-to-hides-skins-and-leather-chd-17-leather-tanning-materials-and-allied-products-1817197.webp)

IS 1640 (2007): Glossary of Terms Relating to Hides, Skins and Leather [CHD 17: Leather, Tanning Materials and Allied Products]

इंटरनेट मानक Disclosure to Promote the Right To Information Whereas the Parliament of India has set out to provide a practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, and whereas the attached publication of the Bureau of Indian Standards is of particular interest to the public, particularly disadvantaged communities and those engaged in the pursuit of education and knowledge, the attached public safety standard is made available to promote the timely dissemination of this information in an accurate manner to the public. “जान का अधकार, जी का अधकार” “परा को छोड न 5 तरफ” Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan Jawaharlal Nehru “The Right to Information, The Right to Live” “Step Out From the Old to the New” IS 1640 (2007): Glossary of terms relating to hides, skins and leather [CHD 17: Leather, Tanning Materials and Allied Products] “ान $ एक न भारत का नमण” Satyanarayan Gangaram Pitroda “Invent a New India Using Knowledge” “ान एक ऐसा खजाना > जो कभी चराया नह जा सकताह ै”ै Bhartṛhari—Nītiśatakam “Knowledge is such a treasure which cannot be stolen” IS 1640:2007 wi,m+k WET * TT1’R$nf$% ● WwI+ll Indian Standard GLOSSARY OF TERMS RELATING TO HIDES, SKINS AND LEATHER (First Revision,) ICS 01.040.59; 59.140.20 0 BIS 2007 BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS MANAK BHAVAN, 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 December 2007 Price Group 16 Leather Tanning Materials and Allied Products Sectional Committee, CHD 17 FOREWORD This Indian Standard (First Revision) was adopted by the Bureau of Indian Standards, after the draft finalized by the Leather, Tanning Materials and Allied Products Sectional Committee had been approved by the Chemical Division Council. -

Hides, Skins, and Leather

Industry\)\) Trade Summary Hides, Skins, and Leather USITC Publication 3015 February 1997 OFFICE OF INDUSTRIES U.S. International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Marcia E. Miller, Chairman Lynn M. Bragg, Vice Chairman Don E. Newquist Carol T. Crawford Robert A. Rogowsky Director of Operations Vern Simpson Director of Industries This report was prepared principally by Rose Steller Agriculture and Forest Products Division Animal and Forest Products Branch Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 PREFACE In 1991 the United States International Trade Commission initiated its current Industry and Trade Summary series of informational reports on the thousands of products imported into and exported from the United States. Each summary addresses a different commodity/industry area and contains information on product uses, U.S. and foreign producers, and customs treatment. Also included is an analysis of the basic factors affecting trends in consumption, production, and trade of the commodity, as well as those bearing on the competitiveness of U.S. industries in domestic and foreign markets.1 This report on hides, skins, and leather covers the period 1991 through 1995 and represents one of approximately 250 to 300 individual reports to be produced in this series. Listed below are the individual SUll1llUII)' reports published to date on the agricultural and forest products sector. USITC publication Publication number date Title 2459 November 1991 ........ Live Sheep and Meat of Sheep 2462 November 1991 ........ Cigarettes 2477 January 1992. Dairy Produce 2478 January 1992 .......... Oilseeds 2511 March 1992 . Live Swine and Fresh, Chilled, or Frozen Pork 2520 June 1992 . -

Valley at Dusk Gary J

College of the Holy Cross CrossWorks Fenwick Scholar Program Honors Projects Spring 1983 Valley at Dusk Gary J. Gala '83 College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://crossworks.holycross.edu/fenwick_scholar Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Gala, Gary J. '83, "Valley at Dusk" (1983). Fenwick Scholar Program. 6. http://crossworks.holycross.edu/fenwick_scholar/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fenwick Scholar Program by an authorized administrator of CrossWorks. garyj gala Valley at Dusk Gary J. Gala Acknowledgements It goes without saying that there are many more people to thank than I have space or time for here. A first never, more than any other work, is probably the most likely place to find outpourings of gratitude for everyone who has touched the author's life, even in the briefest way. However, there are a few who rise above the many, at least as far as my poor memory serves. First, this work would never have been started without the help of my advisor Richard H. Rodino who brought me from ground zero to loftier heights than I could ever have hoped for in a years time. If there are good things in this novel, he deserves the credit for channeling my efforts towards those areas and away from my own misgivings about the workings of fiction. Second, I would like to thank my readers, both official and unofficial who made many significant and helpful contributions along the way.