Vienna Kärntnertortheater Singers in the Letters from Georg Adam Hoffmann to Count Johann Adam Von Questenberg Italian Opera Singers in Moravian Sources C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opera Olimpiade

OPERA OLIMPIADE Pietro Metastasio’s L’Olimpiade, presented in concert with music penned by sixteen of the Olympian composers of the 18th century VENICE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA Andrea Marcon, conductor Romina Basso Megacle Franziska Gottwald Licida Karina Gauvin Argene Ruth Rosique Aristea Carlo Allemano Clistene Nicholas Spanos Aminta Semi-staged by Nicolas Musin SUMMARY Although the Olympic games are indelibly linked with Greece, Italy was progenitor of the Olympic operas, spawning a musical legacy that continues to resound in opera houses and concert halls today. Soon after 1733, when the great Roman poet Pietro Metastasio witnessed the premiere of his libretto L’Olimpiade in Vienna, a procession of more than 50 composers began to set to music this tale of friendship, loyalty and passion. In the course of the 18th century, theaters across Europe commissioned operas from the Olympian composers of the day, and performances were acclaimed in the royal courts and public opera houses from Rome to Moscow, from Prague to London. Pieto Metastasio In counterpoint to the 2012 Olympic games, Opera Olimpiade has been created to explore and celebrate the diversity of musical expression inspired by this story of the ancient games. Research in Europe and the United States yielded L’Olimpiade manuscripts by many composers, providing the opportunity to extract the finest arias and present Metastasio’s drama through an array of great musical minds of the century. Andrea Marcon will conduct the Venice Baroque Orchestra and a cast of six virtuosi singers—dare we say of Olympic quality—in concert performances of the complete libretto, a succession of 25 spectacular arias and choruses set to music by 16 Title page of David Perez’s L’Olimpiade, premiered in Lisbon in 1753 composers: Caldara, Vivaldi, Pergolesi, Leo, Galuppi, Perez, Hasse, Traetta, Jommelli, Piccinni, Gassmann, Mysliveek, Sarti, Cherubini, Cimarosa, and Paisiello. -

9914396.PDF (12.18Mb)

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fece, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Ifigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnaticn Compare 300 North Zeeb Road, Aim Arbor NO 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with indistinct print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available UMI THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO THREE SACRED CHORAL/ ORCHESTRAL WORKS BY ANTONIO CALDARA: Magnificat in C. -

"Lucca Città Della Musica" Di Sara Matteucci

SARA MATTEUCCI Lions Club Lucca Host CLuccaITTÀ DELLA MUSICA Questo volume è un’espressione del progetto “Lucca città della musica” che il Lions Club Lucca Host sta portando avanti negli ultimi anni al fine di far entrare Lucca fra le città UNESCO creative della musica. Il Comitato Cultura del Lions Club Lucca Host, presieduto da Leonardo Odoguardi e com- posto da Riccardo Benvenuti, Michele Bianchi, Francesco Cipriano, Giuliano Marchetti, Cristiano Meossi, Enrico Ragghianti, Antonio Sargenti, è stato supportato dai presidenti del Club Umberto Stefani, Adalberto Saviozzi, Maria Carla Giambastiani e dai soci Cesare Rocchi, Gualberto Del Roso. Si ringraziano tutti coloro che hanno collaborato alla realizzazione di questa pubblicazione ed in particolare l’autrice del lavoro Sara Matteucci e Manifatture Sigaro Toscano. SARA MATTEUCCI CLuccaITTÀ DELLA MUSICA Lions Club Lucca Host Si ringrazia per il contributo CLuccaITTÀ DELLA MUSICA Referenze fotografiche Foto Ghilardi, Lucca; Foto Arnaldo Fazzi, Archivio Maria Pacini Fazzi Editore © Copyright 2010: Lions Club Lucca Host Cura grafica e impaginazione Gabriele Moriconi per Maria Pacini Fazzi Editore, Lucca www.pacinifazzi.it ISBN 978-88-6550-026-2 Lions Club Lucca Host Negli Scopi del lionismo è previsto di «prendere attivo interesse al bene civico, culturale, sociale e mo- rale della comunità», mentre nel Codice dell’etica lionistica si chiede di «dimostrare con l’eccellenza delle opere e la solerzia del lavoro, la serietà della vocazione al servizio». Questo desiderio di incidere positiva- mente nel tessuto cittadino è stato ed è una vocazione congenita al Lions Club Lucca Host. Dalla sua istituzione nel 1955, esso si è impegnato per la valorizzazione del patrimonio culturale ed artistico di una città dalla lunga storia. -

Antonio Caldara

Portus Felicitatis Johann Georg Reutter (1708-1772) MOTETS AND ARIAS FOR THE PANTALEON MOTETTEN UND ARIEN FÜR DAS PANTALEON MOTETS ET ARIAS POUR LE PANTALÉON 1. Aria Venga l'età vetusta 6:59 (from the FESTA DI CAMERA PER MUSICA La magnanimità di Alessandro, 1729) 2. Mottetto de ominibus Sanctis Justorum animae in manu Dei sunt (1732) 5:34 3. Pizzicato 5:29 4. Aria Dura legge a chi t'adora 7:20 (from the FESTA TEATRALE Archidamia, 1727) 5. Allegro 3:20 6. Mottetto de quovis Sancto vel Sancta Hodie in ecclesia sanctorum (1753?) 7:37 7. Mottetto de Sancto Wenceslau Wenceslaum Sanctissimum (1752?) 5:09 8. Aria Del pari infeconda 6:42 (from the AZIONE SACRA La Betulia liberata, 1734) 9. Mottetto de Resurrectione Domini Surrexit Pastor bonus (1748?) 8:13 10. Mottetto de Sanctissima Trinitate Deus Pater paraclytus (1744?) 6:21 11. Aria Soletto al mio caro 6:45 (from the DRAMMA PER MUSICA Alcide trasformato in dio, 1729) TOTAL 69:36 4 Monika Mauch soprano Stanislava Jirků alto La Gioia Armonica Meret Lüthi violin Sabine Stoffer violin Lucile Chionchini viola Felix Knecht cello Armin Bereuter violone Margit Übellacker dulcimer Michael Freimuth archlute, theorbo Jürgen Banholzer organ, direction 5 Th e ensemble La Gioia Armonica was founded by Austrian dulcimer-player Margit Übellacker and German or- ganist and singer Jürgen Banholzer. One of the ensemble's objectives is to explore the baroque repertoire for dulcimer, in particular in connection with the legendary pantaleon. Th e size of the group varies from dulcimer-organ duet to large chamber-music settings. -

Luca Antonio Predieri

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Hudební věda Iva Bittová Luca Antonio Predieri: Missa in C Sacratissimi Corporis Christi Magisterská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Jana Perutková, Ph.D. 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracovala samostatně a pouze s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. ...................................... OBSAH PŘEDMLUVA ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 ÚVOD ..................................................................................................................................................................... 5 1 STAV BÁDÁNÍ .............................................................................................................................................. 6 2 LUCA ANTONIO PREDIERI .................................................................................................................... 12 2.1 ŽIVOTOPIS .............................................................................................................................................. 12 2.2 PŘEHLED DÍLA ........................................................................................................................................ 16 3 EDICE PRAMENE MISSA IN C SACRATISSIMI CORPORIS CHRISTI ......................................... 19 3.1 POPIS PRAMENE ..................................................................................................................................... -

Antonio Vivaldi I La Cantata

PROJECTE FINAL La Cantata a Europa a l’entorn del segle XVIII Música da camera italiana del Barroc tardà Estudiant: Anna Valls i Puig Àmbit/Modalitat: Música antiga / cant històric Director: Lambert Climent Curs: 2012-2013 Vistiplau del Membres del tribunal: director: 1. Lambert Climent 2. Emilio Moreno 3. Albert Romaní AGRAÏMENTS A la Maria Dolors Puig i en Joan Valls, els meus estimats pares, per decidir de donar-me la millor herència, la meva educació. A la meva àvia i al meu avi, Francesca Torrellas i Francesc Puig, per ser un exemple de superació personal. Al Manuel Cabero, per dir-me un dia “nena, a tu no t’agradaria cantar?” A l’Elisenda Cabero, per “picar pedra” i creure en mi. Al Lambert Climent, per aquella frase “tu vols estudiar amb mi, jo et faré lloc” i per la seva gran disponibilitat i generositat docent. A l’Albert Romaní, per ensenyar-me tantes coses amb poques paraules. Al Raúl Coré, un gran bibliotecari, un gran musicòleg, un gran cantant i per sobre de tot, un gran amic. Al Genís Riba, un savi amic. Afortunats aquells que el tinguin al voltant. Al Pedro Beriso, per dedicar-me generosament el seu temps. A la Kathy Leidig, la Marta Carreton i la Belén Doménech, una germana nord americana, una basca i una valenciana sempre disposades a ajudar-me “més”. Als instrumentistes i amics que m’han regalat, generosament, el seu temps i professionalitat acompanyant-me en aquest projecte: Kathy Leidig, Amie Weiss, Leticia Moros, Melodie Roig, Daniel Ramírez, Dimitri Kindynis i Ariadna Cabiró. -

Cangianze: the Deception of Baroque

CANGIANZE: THE DECEPTION OF BAROQUE A JOURNEY INTO THE MODERNITY OF BAROQUE Teatro Caio Melisso Spazio Carla Fendi Sunday, july 10 at 19.30 CANGIANZE: THE DECEPTION OF BAROQUE Created specifically for the fifth edition of the Carla Fendi Foundation Award, a performance combining contemporary arts with the baroque. Three different moments of choir, dance and bel canto. The vocal talent of the Pueri Cantores of the Sistine Chapel. Representing the young, propelling soul and real jewel in the crown of the entire choir, the Pueri Cantores maintain alive a tradition which, albeit with various interruptions, has been around for 15 centuries, contributing to giving value to a musical heritage which is one-of-a-kind. In this performance the choirmeets the words of the poet GIUSEPPE MANFRIDI; on music by SAMUEL BARBER. The versatility of great soloists who “deceive” through unexpected appearances. The Escuela Nacional de Ballet di Cuba: the best European and American academic traditionscombined with the vitality and musicality typical of La Isla Grande; juxtaposed to the baroque music of GIAN BATTISTA LULLY. A voice without boundaries and limitations. The timeless talent of the countertenor Max Emanuele Cenčic, one of the most important figures responsible for rediscovering music from the XVIII century; accompanied by the baroque ensemble IL POMO D’ORO. Cangianze : like the mutation and contemporary rewriting of Baroque Theatre, or of “the deception.” PUERI CANTORES OF THE SISTINE CHAPEL The Pueri Cantores of the Sistine Chapel make up the section of white voices of the Pontifical Musical Choir. Representing the young, propelling soul and real jewel in the crown of the entire choir, and required to carry out musical studies for five intense years, the Pueri Cantores maintain alive a tradition which, albeit with various interruptions, has been around for 15 centuries, contributing to giving value to a one-of-a-kind musical heritage. -

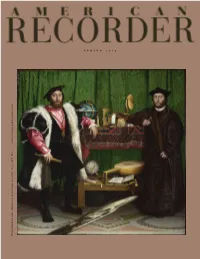

S P R I N G 2 0

Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. LIV, No. 1 • www.americanrecorder.org spring 2013 SOPRANINO TO SUBBA SS A WELL-TUNED CON S ORT www.moeck.com Anzeige_Orgel_A4.indd 1 11.11.2008 19:21:44 Uhr Lost in Time Press New works and arrangements for recorder ensemble Compositions by Frances Blaker Paul Ashford Hendrik de Regt and others Inquiries: Corlu Collier PMB 309 2226 N Coast Hwy Newport, Oregon 97365 www.lostintimepress.com [email protected] Dream-Edition – for the demands of a soloist Enjoy the recorder Mollenhauer & Adriana Breukink Enjoy the recorder Dream Recorders for the demands of a soloist New: due to their characteristic wide bore and full round sound Dream-Edition recorders are also suitable for demanding solo recorder repertoire. These hand-finished instru- ments in European plumwood with maple decorative rings combine a colourful rich sound with a stable tone. Baroque fingering and double holes provide surprising agility. TE-4118 Tenor recorder with ergonomic- ally designed keys: • Attractive shell-shaped keys • Robust mechanism • Fingering changes made TE-4318 easy by a roll mechanism fitted to double keys • Well-balanced sound a1 = 442 Hz Soprano and alto in luxurious leather bag, tenor in a hard case TE-4428 www.mollenhauer.com Soprano Alto Tenor (with double key) TE-4118 Plumwood with maple TE-4318 Plumwood with maple TE-4428 Plumwood with maple decorative rings decorative rings decorative rings Editor’s ______Note ______ ______ ______ ______ Volume LIV, Number 1 Spring 2013 efore you ask: yes, that’s a skull on the Features cover of this issue. -

The Chalumeau in Eighteenth-Century Vienna: Works for Soprano and Soprano Chalumeau Elizabeth Crawford

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Chalumeau in Eighteenth-Century Vienna: Works for Soprano and Soprano Chalumeau Elizabeth Crawford Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE CHALUMEAU IN EIGHTEENTH - CENTURY VIENNA: WORKS FOR SOPRANO AND SOPRANO CHALUMEAU By ELIZABETH CRAWFORD A Treatise submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Elizabeth Crawford defended on March 17, 2008. ________________________________ Frank Kowalsky Professor Directing Treatise ________________________________ James Mathes Outside Committee Member ________________________________ Jeff Keesecker Committee Member ________________________________ John Parks Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii Dedicated to my mother and to the memory of my father. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee – Dr. Frank Kowalsky, Professor Jeff Keesecker, Dr. Jim Mathes, and Dr. John Parks – for their time and guidance. Thanks also to the staff of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek for their assistance and to Eric Hoeprich for his insight and patience. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical Examples . vi Preface . vii Chapter 1 – The Chalumeau . 1 Chapter 2 – Italian Influence in Vienna . 8 Chapter 3 – Musical Life at Court . 13 Chapter 4 – Giovanni Bononcini (1670-1747) . 17 Chapter 5 – Joseph I, Habsburg (1678-1711) . 23 Chapter 6 – Johann Joseph Fux (1660-1741) . -

Música I Política a L'època De L'arxiduc Carles En El Context Europeu

Música i política a l’època de l’arxiduc Carles en el context europeu Tess Knighton Ascensión Mazuela (ed.) Juan José Carreras Danièle Lipp Andrea Sommer-Mathis José María Domínguez Álvaro Torrente Xavier Torres Lluís Bertran Musica y politica en epoca Carlos III_INT.indd 1 22/06/2017 10:53:46 Consell d’Administració de l’Institut Consell d’Edicions i Publicacions de cultura de Barcelona: de l’Ajuntament de Barcelona: President: Gerardo Pisarello Prados, Josep M. Montaner Jaume Collboni Cuadrado Martorell, Laura Pérez Castallo, Jordi Campillo Vicepresidenta: Gámez, Joan Llinares Gómez, Marc Andreu Gala Pin Ferrando Acebal, Águeda Bañón Pérez, José Pérez Freijo, Pilar Roca Viola, Maria Truñó i Vocals: Salvadó, Anna Giralt Brunet Jaume Ciurana i Llevadot, Joan Josep Puigcorbé i Benaiges, Pau Guix Pérez, Guillem Espriu Avendaño, Alfredo Bergua Valls, Pere Casas Zarzuela, Ricard Vinyes Ribas, Martina Millà Bernad, Arantxa García Terente, Fèlix Ortega Sanz, Antonio Ramírez González, Núria Sempere Comas, Eduard Escoffet Coca Secretària: Montserrat Oriol Bellot Gerent: Valentí Oviedo Cornejo Coordinació editorial: Ana Shelly Correcció català i castellà: Joan Lluís Quilis Disseny de coberta: Carlos Ortega i Jaume Palau Maquetació: Addenda Impressió: Crown Quarto, S.L. Primera edició: maig 2017 © de l’edició: Museu d’Història de Barcelona, Institució Milà i Fontanals (IMF), Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (ICREA), Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions © dels texts: els seus autors © de les imatges: Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona (AHCB), Biblioteca Nacional de Catalunya (BNC), Biblioteca Nacional Austríaca, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung. Imatge de coberta: Cant dels aucells quant arriben los vaxells devant de Barcelona, y del desembarch de Carles III, 1705 (?). -

Download Booklet

CONVERSAZIONI II Duelling Cantatas Sounds Baroque Anna Dennis soprano Andrew Radley countertenor Julian Perkins director Noelle Barker OBE (1928–2013) Sounds Baroque was privileged to have had Noelle Barker as its first honorary patron. In addition to being a distinguished soprano, Noelle was a formidable teacher and a refreshingly honest friend. Her indefatigable support was invaluable in launching this series of conversazioni concerts and recordings. Conversazioni II is dedicated to her memory. 2 CONVERSAZIONI II Duelling Cantatas Sounds Baroque Jane Gordon and Jorge Jimenez violins Jonathan Rees cello and viola da gamba James Akers archlute, guitar and theorbo Frances Kelly triple harp Anna Dennis soprano Andrew Radley countertenor Julian Perkins harpsichord, organ and director 3 Francesco Gasparini (1668–1727) Io che dal terzo ciel (Venere e Adone) 24:26 1 Recitativo – Io che dal terzo ciel raggi di gioia (Venere) 1:00 2 Aria – Come infiamma con luce serena (Venere) 2:32 3 Recitativo – Se già nacqui fra l’onde (Venere) 0:49 4 Aria – T’amerò come mortale (Adone) 3:22 5 Recitativo – Non m’adorar, no, no (Venere) 0:23 6 Aria – Tutto il bello in un sol bello (Venere) 2:08 7 Recitativo – È il mio volto mortale (Adone) 0:21 8 Aria – Ove scherza il ruscel col ruscello (Venere e Adone) 1:37 9 Recitativo – Del ruscel dell’augello il canto e’l suono (Venere e Adone) 0:34 10 Aria – La pastorella ove il boschetto ombreggia (Venere e Adone) 4:12 11 Recitativo – Qual farfalletta anch’io (Venere e Adone) 1:03 12 Aria – Meco parte il mio dolore (Venere) 1:49 13 Recitativo – Ecco ti lascio, o caro (Venere e Adone) 0:36 14 Aria – Usignol che nel nido sospira (Venere e Adone) 3:54 Antonio Caldara (c1670–1736) Trio sonata in E minor, op. -

The Harpsichord: a Research and Information Guide

THE HARPSICHORD: A RESEARCH AND INFORMATION GUIDE BY SONIA M. LEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Chair and Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus Donald W. Krummel, Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus John W. Hill Associate Professor Emerita Heidi Von Gunden ABSTRACT This study is an annotated bibliography of selected literature on harpsichord studies published before 2011. It is intended to serve as a guide and as a reference manual for anyone researching the harpsichord or harpsichord related topics, including harpsichord making and maintenance, historical and contemporary harpsichord repertoire, as well as performance practice. This guide is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide a user-friendly resource on the subject. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation advisers Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch and Professor Donald W. Krummel for their tremendous help on this project. My gratitude also goes to the other members of my committee, Professor John W. Hill and Professor Heidi Von Gunden, who shared with me their knowledge and wisdom. I am extremely thankful to the librarians and staff of the University of Illinois Library System for assisting me in obtaining obscure and rare publications from numerous libraries and archives throughout the United States and abroad. Among the many friends who provided support and encouragement are Clara, Carmen, Cibele and Marcelo, Hilda, Iker, James and Diana, Kydalla, Lynn, Maria-Carmen, Réjean, Vivian, and Yolo.