1 Book of Exodus, Session 8 the Golden Calf Exodus 32–34 With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOD's GREATEST SIN Rosh Hashanah Second Day October 1

GOD’S GREATEST SIN Rosh Hashanah Second Day October 1, 2019 2 Tishri 5780 Rabbi Jennifer R. Greenspan I have found, at least in my life, that we are often our own worst critics. We expect too much of ourselves, and we overuse the word “should,” trying desperately to reach some unattainable goal of perfection. I should be able to work a full-time job, maintain a clean home, cook and serve three healthy meals a day, and find at least an hour a day for exercise. I should be able to find time to meditate, go to bed earlier, get up earlier, still get eight hours of sleep, drink more water, and start a yoga routine. I should stop buying things I don’t need and be better about saving money. I should stop using disposable bottles, plastic straws, and eating anything that isn’t organic. I should come to synagogue more often. I should stop looking at my phone. I should use my phone to make sure I’m on top of my calendar. I should spend more time with my family. I should figure out how to be perfect already. How many of those “should”s that we constantly tell ourselves are really true to who we are, and how many come from a culture of perfectionism? When we are sitting in a season of judgement, how are we to judge ourselves and our deeds and our sins when we know we’re not perfect? In the Talmud, Rabbi Abbahu asks: Why on Rosh Hashanah do we sound a shofar made from a ram’s horn? אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא: תקעו לפני בשופר של איל כדי שאזכור לכם עקידת יצחק The Holy Blessed One said: use a shofar made from a ram’s horn, so that I will be reminded of the -

From Gods to God

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters University of Nebraska Press 2012 From Gods to God Avigdor Shinan Yair Zakovitch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Shinan, Avigdor and Zakovitch, Yair, "From Gods to God" (2012). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 130. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/130 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. From Gods to God Buy the Book University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln Buy the Book FROM GODS TO God How the Bible Debunked, Suppressed, or Changed Ancient Myths & Legends avigdor shinan & yair zakovitch Translated by Valerie Zakovitch The Jewish Publication Society Philadelphia Buy the Book English translation © 2012 by Avigdor Shinan and Yair Zakovitch. Lo kakh katuv ba-Tanakh © 2004 by Miskal-Yedioth Ahronoth Books and Chemed Books. All rights reserved. Published by the University of Nebraska Press as a Jewish Publication Society book. Manufactured in the United States of America. ∞ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zakovitch, Yair. [Lo kakh katuv ba-Tanakh. English] From gods to God: how the Bible debunked, suppressed, or changed ancient myths and legends / Yair Zakovitch and Avigdor Shinan; translated by Valerie Zakovitch. p. cm. “Published by the University of Nebraska Press as a Jewish Publication Society book.” Includes bibliographical references and index. -

I C U: 35 Days to Revive My Faith

I C U: 35 Days to Revive My Faith Revelation 3:20 tells us that Jesus not only came to redeem us 2000 years ago, but every day pursues us - personally, persistently. Over the next 5 weeks, we will take a few minutes every day to open the door again to the work of God in our lives. Outside of the work on the cross and the empty tomb on the third day, God has given us another incredible gift: the gift of His word. It is through His word, the Bible, that God continues to speak, revive, and restore broken lives, dreams, and souls. I invite you to set aside 15 minutes, 5 days a week to open the door again to the work of God. Suggested daily outline: read 2 Timothy 3:16-17, pray, read the devotional, write a simple response to the devotional, and work on the weekly memory verse throughout the day ___________________ Week Five Sermon -- Making the Broken Pieces Fit: Dinah This week’s emphasis: Multiplying in Another (Coaching) Day One Read Luke 1:1-66 Elizabeth to Mary When you are “greatly troubled” do you have other believers you can open up to? Mary ran to Elizabeth, who was a truth teller in her life: “blessed are you!” Do you have someone in your life that can help you see the blessing through your troubles? It is important to find others who can lovingly walk through life with you, impart wisdom, truth, and remind you of God’s purpose and plan in your life, especially when you are under stress. -

B a P T I S M

SCOUTING in AMERICA, BSA RELIGIOUS EMBLEMS for the Episcopal Church USA Grades 1-3 B A P T I S M I WANT TO WALK AS A CHILD OF THE LIGHT ADULT LEADER / COUNSELOR’S GUIDE I. HOLY BAPTISM (grades 1-3) II. COMMUNION (grades 4-6) III. CONFIRMATION (grades 7-9) IV. RELATIONSHIPS (grades 10-12) prepared by the Rev’d Edward K. Erb under the auspices of the Episcopal Scouters’ Association and the Brotherhood of St. Andrew with permission from P.R.A.Y. 10-2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS page 1 Introduction 2 Outline of the Student book and description of sessions 3 Suggestions & Helpful Hints 6 “Answer” sheets for Water and Word Search 7 Exodus: The Game, instructions, shopping list, and resources Additional Resources Good News Translation® (Today’s English Version, Second Edition) © 1992 American Bible Society. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Bible text from the Good News Translation (GNT) is not to be reproduced in copies or otherwise by any means except as permitted in writing by American Bible Society, 101 North Independence Mall East, Floor 8, Philadelphia, PA 19106-2155 (www.americanbible.org). INTRODUCTION Thank you for agreeing to help our (your) Scouts with their Religious Emblems. This set was written by an Episcopal priest, 30-year Adult Scouter, and recipient of the St. George Award. The series is conceived to be a via media between the Roman Catholic and the general Protestant awards. Subsequent editions are planned to include resources from The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), The United Methodist Church (UMC) and other denominations in Full Communion with the Episcopal Church with a sacramental basis. -

The PAS and American Abolitionism: a Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War

The PAS and American Abolitionism: A Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War By Richard S. Newman, Associate Professor of History Rochester Institute of Technology The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was the world's most famous antislavery group during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, although not as memorable as many later abolitionists (from William Lloyd Garrison and Lydia Maria Child to Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth), Pennsylvania reformers defined the antislavery movement for an entire generation of activists in the United States, Europe, and even the Caribbean. If you were an enlightened citizen of the Atlantic world following the American Revolution, then you probably knew about the PAS. Benjamin Franklin, a former slaveholder himself, briefly served as the organization's president. French philosophes corresponded with the organization, as did members of John Adams’ presidential Cabinet. British reformers like Granville Sharp reveled in their association with the PAS. It was, Sharp told told the group, an "honor" to be a corresponding member of so distinguished an organization.1 Though no supporter of the formal abolitionist movement, America’s “first man” George Washington certainly knew of the PAS's prowess, having lived for several years in the nation's temporary capital of Philadelphia during the 1790s. So concerned was the inaugural President with abolitionist agitation that Washington even shuttled a group of nine slaves back and forth between the Quaker State and his Mount Vernon home (still, two of his slaves escaped). The PAS was indeed a powerful abolitionist organization. PAS Origins The roots of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society date to 1775, when a group of mostly Quaker men met at a Philadelphia tavern to discuss antislavery measures. -

The Greatest Mirror: Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha

The Greatest Mirror Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha Andrei A. Orlov On the cover: The Baleful Head, by Edward Burne-Jones. Oil on canvas, dated 1886– 1887. Courtesy of Art Resource. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2017 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production, Dana Foote Marketing, Fran Keneston Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Orlov, Andrei A., 1960– author. Title: The greatest mirror : heavenly counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha / Andrei A. Orlov. Description: Albany, New York : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016052228 (print) | LCCN 2016053193 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438466910 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438466927 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal books (Old Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS1700 .O775 2017 (print) | LCC BS1700 (ebook) | DDC 229/.9106—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016052228 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For April DeConick . in the season when my body was completed in its maturity, there imme- diately flew down and appeared before me that most beautiful and greatest mirror-image of myself. -

Aaron and the Golden Calf in the Rhetoric of the Pentateuch

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences Fall 2011 Aaron and the Golden Calf in the Rhetoric of the Pentateuch James W. Watts Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Watts, James W. "Aaron and the Golden Calf in the Rhetoric of the Pentateuch." Journal of Biblical Literature 130 (2011), 417-430. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JBL 130, no. 3 (2011): 417–430 Aaron and the Golden Calf in the Rhetoric of the Pentateuch james w. watts [email protected] Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244-1170 In the Pentateuch, the contrast between legal or instructional material, on the one hand, and stories, on the other, is nowhere more stark than in the relationship between the story of the golden calf (Exodus 32–34) and the instructions and nar- ratives (Exodus 25–31; 35–40) that surround it. The story tells of ritual failure with disastrous consequences, while the ritual instructions and narratives around it recount fulfilling those divine instructions to the letter. The contrast becomes most excruciating in each section’s characterization of the high priest: the golden calf story seems to vilify Aaron by placing him at the center of the idolatrous event, while the ritual texts celebrate Aaron and his sons as divinely consecrated priests. -

“Turn in Repentance to Your Creator, Then Slay Yourselves”: the Levitical Election, Atonement, and Secession in Early and Classical Islamic Exegesis1

[CIS 6.1–2 (2010) 101–150] Comparative Islamic Studies (print) ISSN 1740-7125 doi: 10.1558/cis.v6i1–2.101 Comparative Islamic Studies (online) ISSN 1743-1638 “Turn in Repentance to your Creator, then Slay Yourselves”: The Levitical Election, Atonement, and Secession in Early and Classical Islamic Exegesis1 Michael E. Pregill Elon University, Elon, NC [email protected] In memory of Thomas Sizgorich ABSTR A CT The quranic retelling of the Golden Calf story found at 2:51–54 contains a unique allusion to what is arguably one of the most important elements in the biblical precursor in Exodus, the so-called Levitical election. This paper will explore the interpretation of Moses’ puzzling command to the Israelite idolaters to “slay yourselves” in early and classical tafsīr. I will argue that the subtle changes in Muslim exegetes’ understanding of this aspect of the episode reflect important developments in early Islamic soci- ety, in particular the emergence of the accommodationist political ideol- ogy that would become one of the defining features of classical Sunnism. Keywords Biblical stories in Islam, Exodus in Islam, Golden Calf in Islam, Quran, sectarianism, Tafsīr, violence 1. ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������I delivered an early draft of this paper at the Society of Biblical Literature meet- ing in Boston in 2008, on a panel I organized entitled “The Muslim Bible: Islamic Visions of Israel’s History.” I thank the attendees and my fellow panelists for their helpful comments and questions. -

1 the GOLDEN CALF in PSALM 22 George W. Coats the Narrative In

THE GOLDEN CALF IN PSALM 22 George W. Coats The narrative in Exodus 32 describes the tragic event in Israel's wilderness experience marked by construction of the Golden Calf. According to the tale in these verses, Moses had left the people, apparently in the care of Aaron, in order to climb the Mountain for an audience with God. The problem posed by the narrative, the plot at the foundation of the tale, emerges with clarity in the first verses of the unit. Now anxious because Moses tarried so long on the Mountain, the people address Aaron with instructions designed to resolve the source of their anxiety: "Up! Make us gods who shall go before us. As for this Moses, the man who brought us up out of the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him." In the face of their anxiety, the people call for Aaron to construct gods who could continue the leadership for the people in their journey through the wilderness. The present form of the text interprets this speech as rank heresy. Not only do the people request construction of an object that would serve as leader of the exodus and wilderness journey, an object defined as gods and thus as an idol that violates the second commandment, but they also identify the object as "gods" and thus violate the first commandment. Indeed, the noun is plural, constructed with a plural verb. The first commandment prohibits service of other gods, a noun also clearly defined as plural by the plural adjective that follows it. -

THE PALINDROMIC DEAD SEA SCROLLS Pent Feigns but God Is N LIVE NOT 0 Almighty Del MOOD SEV ERE HOWARD RICHLER Displays Zen Cote St

150 REV ILED I I THE PALINDROMIC DEAD SEA SCROLLS pent feigns but God is n LIVE NOT 0 Almighty del MOOD SEV ERE HOWARD RICHLER displays zen Cote St. Luc, Quebec, Canada EVE DAMNED as God evict Many Biblical scholars are expecting a bombshell with the recent release of previously- unpublished documents of the Dead Sea Scrolls. CAIN, A MOl They will not be disappo i nted i.n discove ring that there another Abel in a cl document which traces the l1istory of the Bible in palindromic form. HA' ON' ON' Not only is thi.s document written palindromically, but it is writ of Arc, is ir ten in English palindromes. WAS IT ARA One should not be totally surprised at this revelation, for there the seventh are indications of the favored status of English; it has become a double-tak the lingua franca for a reason. Just as the Jews were the Chosen People, English has become the Chosen Language, supplanting "PEE? WE E Hebrew and Aramaic. his uncle A Genesis 17) J The facts speak for themselves. Examine the Biblica1 names Eve, Hannah, Asa , Adam, Anna, Onan. Ahab, Mo ses, Annas and PA'S A SAP' Jesus. All these names a re e ither palindromes o r near-palindromes' his two dauf Wa s not Joshua the son of Nun ? Was not David the son of Jesse? so the elde~ Wa s not Janna the great-grea t-grea t-grandfather of Jesus? Was drunk he w( not Aram the great-great-great-great-grandson of Abraham? The girls bear s Biblica1 place-names Eden, Canaan, Tarsus, Gaza, Cana and Ararat i tes. -

The Golden Calf: NO Idols Exodus 32:1-14 When the People Saw That

The Golden Calf: NO Idols Exodus 32:1-14 When the people saw that Moses delayed to come down from the mountain, the people gathered around Aaron, and said to him, "Come, make gods for us, who shall go before us; as for this Moses, the man who brought us up out of the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him." He took the gold from them, formed it in a mold, and cast an image of a calf; and they said, "These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt!" Exodus 32:1, 4 For a while, the Israelites stopped worshipping God who brought them out of slavery in Egypt. THEY MADE their own god to worship—a golden calf. God did not like it! We only should worship our one, true God—not things made by ourselves or others. Supplies: 1 paper plate 2 wooden clothes pins or something else to use as legs Golden calf head template Tape Yellow/gold crayon Scissors 1. Color the golden calf head cut out gold/yellow. 2. Either write on the outer side of the paper plate (with a marker) or cut out pieces of paper and write the name of things we sometimes can love too much—even more than God to remind us to be careful to love God first and most. (things like money, stuff) 3. Color the paper plate golden 4. Fold the paper plate in half and put two clothes pins at the bottom for its feet. -

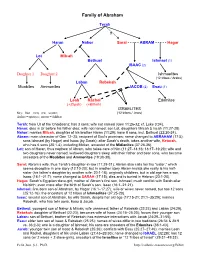

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20).