Cultural Centers of Color: Report on a National Survey. INSTITUTION Nustats, Inc., Austin, TX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

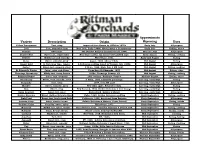

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Handling of Apple Transport Techniques and Efficiency Vibration, Damage and Bruising Texture, Firmness and Quality

Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences PUBLISHED BY: B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACTIVITIES OF WP9 IN THE CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE AGROPHYSICS CONTRACT NO: QLAM-2001-00428 CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR APPLIED PHYSICS IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE WITH THE th ACRONYM AGROPHYSICS IS FOUNDED UNDER 5 EU FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH, TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION ACTIVITIES GENERAL SUPERVISOR OF THE CENTRE: PROF. DR. RYSZARD T. WALCZAK, MEMBER OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES PROJECT COORDINATOR: DR. ENG. ANDRZEJ STĘPNIEWSKI WP9: PHYSICAL METHODS OF EVALUATION OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE QUALITY LEADER OF WP9: PROF. DR. ENG. BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI, JR. REVIEWED BY PROF. DR. ENG. JÓZEF KOWALCZUK TRANSLATED (EXCEPT CHAPTERS: 1, 2, 6-9) BY M.SC. TOMASZ BYLICA THE RESULTS OF STUDY PRESENTED IN THE MONOGRAPH ARE SUPPORTED BY: THE STATE COMMITTEE FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNDER GRANT NO. 5 P06F 012 19 AND ORDERED PROJECT NO. PBZ-51-02 RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF POMOLOGY AND FLORICULTURE B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ©Copyright by BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES LUBLIN 2006 ISBN 83-89969-55-6 ST 1 EDITION - ISBN 83-89969-55-6 (IN ENGLISH) 180 COPIES, PRINTED SHEETS (16.8) PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER IN POLAND BY: ALF-GRAF, UL. -

Marktbericht Für Die Obstregion Bodensee

Marktbericht für die Obstregion Bodensee 50. Jahrgang, Nr. 09 Mittwoch, den 1. September 2010 Aufnahmefähig er Markt Frankr. lose 132150 Der Verkauf der Frühsorten ist durch die guten Absatzmöglichkeiten wei- Niederl. lose 90 90 terhin flüssig. Im Gegensatz zum Vorjahr ist genügend Spielraum zur Plat- Gala Spanien 75/80 144144 zierung von Tafeläpfeln vorhanden, sodass sich die Preislage deutlich stabi- Goden D. Frankr. 75/80 165 0 ler gestaltet als zu Beginn der letzten Saison. Aus Südtirol erreichten erste Italien 70/75 105105 Gala den deutschen Markt. G. Smith Frankr. lose 125108 Spanien lose 152156 Gravenst. Deutschl. lose 129135 Jamba Deutschl. lose 81 85 Bodensee J. Grieve Deutschl. lose 100 110 In der vergangenen Woche gab es Jerseymac Frankr. lose 85 84 Aktuelle Notierung vom 31. August Jonagold Deutschl. lose 62 72 auf dem Apfelmarkt durch die zu- 2010, Kl.1, in €/dt Jonagored Deutschl. lose 55 56 friedenstellende Nachfrage ausrei- Woche 35 ± Abst. 23 20 Sonst. Sorten Deutschl. lose 107 110 chend Möglichkeiten zum Absatz Delbarestivale Niederl. lose 130130 von Frühäpfeln und Birnen. Das be- 75/80/90 75 9:0 - - Summerred Deutschl. lose 98101 traf vor allem Delbarestivale und 70/75 70 9:0 - - Royal Gala Deutschl. lose 123 0 Summered. Ebenfalls im Sortiment 65/70 55 7:2 - - Frankr. lose 128132 60/65 44 7:2 - - vertreten sind Gravensteiner, Dis- Italien lose 112 115 70+ Kl.2 40 8:0 - - covery, Piros und Lodi. In der ers- Birnen Elstar CA Abate Fetel Italien 75/80 210 0 ten Notierung der neuen Saison 80/85 75 8:0 - 57 wurde neben Delbarestivale und C. -

Assessing the Environmental Adaptation of Wildlife And

Assessing the Environmental Adaptation of Wildlife and Production Animals Production and Wildlife of Adaptation Assessing Environmental the Assessing the Environmental Adaptation of Wildlife and • Edward Narayan Edward • Production Animals Applications of Physiological Indices and Welfare Assessment Tools Edited by Edward Narayan Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Animals www.mdpi.com/journal/animals Assessing the Environmental Adaptation of Wildlife and Production Animals: Applications of Physiological Indices and Welfare Assessment Tools Assessing the Environmental Adaptation of Wildlife and Production Animals: Applications of Physiological Indices and Welfare Assessment Tools Editor Edward Narayan MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Edward Narayan The University of Queensland Australia Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Animals (ISSN 2076-2615) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/animals/special issues/ environmental adaptation). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-0365-0142-0 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-0365-0143-7 (PDF) © 2021 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher areproperly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. -

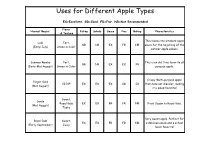

Uses for Different Apple Types

Uses for Different Apple Types EX=Excellent, GD=Good, FR=Fair, NR=Not Recommended Flavor Harvest Begins: Eating Salads Sauce Pies Baking Characteristics & Texture This makes the ultimate apple Lodi Tart, NR NR EX FR NR sauce for the beginning of the (Early July) Green in Color summer apple season. Summer Rambo Tart, This is an old-time favorite all- NR NR EX EX FR (Early-Mid August) Green in Color purpose apple. Crispy Multi-purpose apple Ginger Gold CRISP EX EX EX GD GD that does not discolor, making (Mid August) it a salad favorite! Sweet, Sansa Royal Gala EX EX FR FR NR First Cousin to Royal Gala. (Mid August) Taste Very sweet apple. Perfect for Royal Gala Sweet, EX EX FR FR NR a delicous snack and a school (Early September) Juicy lunch favorite! Extremely popular sweet Honey Crisp tasting apple. Our most crispy CRISP EX EX EX EX FR (Early September) and juiciest apple perfect for a sweet snack! MacIntosh Semi-Sweet/ General all purpose apple. EX GD EX EX FR (Mid September) Tart Nice sweet-tart apple. Exclusively sold at Milburn Orange Honey Sweet, EX EX EX EX FR Orchards. Some say equal to (Mid September) Crisp Honey Crisp! Crispy, tart flavor. This apple is available before Stayman Jonathan CRISP/ EX GD GD EX EX Winesap and a perfect (Mid September) Tart substitute. Multi-Purpose apple. Cortland Semi- Multi-Purpose apple. Next GD GD EX EX FR (Mid September) Tart best thing to MacIntosh. Sweet, An offspring of Fuji, same September Fuji Juicy, EX EX GD EX GD qualities but 4 weeks (Mid September) Not very earlier. -

Ranking of Dog Events Many Clubs Have Two Or More Shows Each Year

Ranking of Dog Events Many clubs have two or more shows each year. The number in parenthesis indicates the month and day of the show. Note: Ties for shows with the same number of entries have the same ranking. SHOW AND LOCATION DOGS IN POSITION COMPETITION ALL BREED SHOWS 2002 2001 2002 2001 Ashtabula KC,(07/13),Madison,OH ................. 914 1000 706 586 Atlanta KC,(09/21),Atlanta,GA ........................ 2152 1927 51 99 TOP 25 ALL BREED SHOWS BY ENTRY Augusta KC,(10/05),North Augusta,SC........... 370 383 1384 1360 Austin KC,(07/13),San Antonio,TX.................. 2117 1707 57 152 SHOW AND LOCATION DOGS IN POSITION Austin KC,(07/11),San Antonio,TX.................. 1736 1623 144 179 COMPETITION Back Mountain KC,(11/02),Bloomsburg,PA .... 1054 875 533 735 2002 2001 2002 2001 Back Mountain KC,(11/03),Bloomsburg,PA..... 945 N/C 663 N/C Badger KC,(05/05),Madison,WI ...................... 1863 1741 116 140 Kennel Cl Palm Springs,(01/05),Indio,CA................... 3457 3349 1 2 Badger KC,(05/03),Madison,WI ...................... 1381 1202 283 392 Kennel Cl Palm Springs,(01/06),Indio,CA................... 3254 3220 2 7 Bahia Sur KC of Chula Vis,(06/15), Kennel Cl Columbus IN,(03/15),Louisville,KY............ 3213 3239 3 6 Chula Vista,CA............................................. 854 912 784 692 Evansville KC,(03/16),Louisville,KY ............................. 3205 3336 4 3 Bahia Sur KC of Chula Vis,(06/16), Louisville KC,(03/17),Louisville,KY............................... 3117 3244 5 5 Chula Vista,CA............................................. 822 898 826 710 Beaver Co KC,(08/03),Canfield,OH ........................... -

Assessment of One Year of Growth in the New Jersey Hard Cider Variety Trial M

Assessment of One Year of Growth in the New Jersey Hard Cider Variety Trial M. Muehlbauer and R. Magron Rutgers University There is much interest in hard cider in New Jersey. the best apples for their cider. Some traditional fresh In New Jersey the manufacture of hard cider is covered market apples make good hard cider, but many of the under the Farm Winery Act, passed in 1981. NJ law hard cider producers are looking for both the English treats hard cider as a type of wine as it is fermented and French hard cider varieties to source for production from fruits (N.J.A.C. 18:3-1.2) of craft hard ciders. As such there is much interest from existing sweet Apple growers and hard cider producers are look- cider producers to make and sell hard cider as a value ing to source these hard cider apple varieties that have added product. There is also great interest and for the specifi c characteristics for craft hard cider. There is an establishment of new, stand alone hard cideries. NJ now abundant interest and momentum from these NJ hard has a mix of both established, seen the list at https:// cider producers to evaluate and grow or purchase these www.ciderculture.com/cideries/state/nj/ varieties from other apple growers. These hard cider producers all need a supply of As a result, it is important to establish a demonstra- ϴϬ ϳϬ ϲϬ ϱϬ ϰϬ ϯϬ ϮϬ $YHUDJH +HLJKW LQ $YHUDJH 'LDPHWHU PP ϭϬ Ϭ /RGL 0DMRU /LQGHO 0DUJLO &ROODRV 'DELQHWW +DUULVRQ :LFNVRQ )R[ZKHOS 0DULDOHQD %ODQTXLQD (OOLV%LWWHU 3LQN3HDUO 6WRNH5HG 3LHOGH6DSD &DOYLOOH%ODQF %OXH3HDUPDLQ -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Form 9 9 0 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c ), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung Department of the Treasury benefit trust;, or private foundation) have this return satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Serace ► The organization m ay to use a copy of to A for the 4uu t cale nalar y ear , or tax y ear oe mnm mow/ ana enarn B Check it applicable Please C Name of organization D Employer Identification number Addrecc use IRS Change label or THRIVENT FINANCIAL FOR LUTHERANS-GROUP RETURN 51-0200276 print or Name change Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number type. Initial return see 625 FOURTH AVENUE SOUTH , MAIL STOP 1370 612 844-8263 Specific Termination lnstn,c- City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 Atooun1opmethod LX Cash Accrual Ame nded dons. 41 Other ( s p ecif y) r et urn MINNEAPOLIS MN 55 5 ► Applicapendin tion • H and I are not applicable to section 527 o anizations pendin g Section 501 ( c )1 3 1 org anizations and 4947 ( a )l 1 1 nonexem pt charitable rg trusts must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates' D Yes q No H(b) If "Yes ," enter number of affiliates G Website : ► WWW. THRI VENT . COM ► 1362 _ Are all affiliates included? X Yes ^No J Organization type ( check only one) ► }{ 501 ( c) (8 ) -4 (Insert no ) 14947 ( a)(1) or 527 H (c) (If "No," attach a list See instructions K Check here if the organization is not a 509 ( a)(3) supporting organization and its gross ► H(d) Is this a separate return filed by an receipts are normally not more than $25,000 A return is not required , but if the organization chooses org an i zat ion covered by a u p rul n Yes }{ Nc to file a return , be sure to file a complete return I Group Exemption Number ► 0285 M Check ► if the organization is not required 990-EZ or 990-PF) L Gross receipts Add lines 6b , 8b, 9b , and 10b to line 12 ► 141 977 997. -

The Los Angeles Academy of Vocal Arts

University of Central Florida STARS Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers Digital Collections 6-7-1982 Application for Grant: The Los Angeles Academy of Vocal Arts Harrison Price Company Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Harrison Price Company, "Application for Grant: The Los Angeles Academy of Vocal Arts" (1982). Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers. 121. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice/121 I I I l I I I APPLICATION FOR GRANT Prepared for : I · Th e Los An geles Academy of Vocal Arts I June 7 , 1982 I I I I I I I I I I I I HARRISON PRICE COMPANY I June 7, 1982 I Mr. Daniel Selznick Louis B. Mayer Foundation 9441 Wilshire Boulevard I Beverly Hills, CA 90212 I Dear Mr . Selznick: The purpose of this letter is to submit to the Louis B. Mayer Fo undation an application for a planning grant for and I on behalf of the Los Angeles Academy of Vocal Arts. The Lo s Angeles Academy of Vocal Arts is a proposed teaching institution formed under the leadership and direction of Mr. I Seth Riggs. Its program will offer a comprehensive and intensive instruction for a full time enrollment of 20 singers with recognized talent and professional potential . -

DOLLAR Pit at Nearby St

Navy's Ecology Price Tag: $1 Billion WASHINGTON (UPI/AFRTS)---The Navy will need $1 billion and ten years to clean up its pollution, the service's top envi- ronmental officer said. THE Cdr. J.A. D'Emidio said the price tag includes funds for on- ship sewage treatment facilities for all 650 Navy vessels, ENVIRONMENT shoreside incinerators and trash disposal, cleaner jet engines and control of oil discharges. as NAVAL eA Lpe LANTANA 9AY. amA ,Am CAVE-IN feared dead CHICOUTIMI, 30Que. (AP/AFRTS)---More than 200 rescue workers hampered by driving rain pushed THURSDAY, MAY 6, 1971 Phone 9-5247 through a sea of mud yesterday searching for survivors of a giant earth cave-in which may have claimed 30 lives. Police said at least 28 persons were missing. The bodies of a young girl and a man were recovered. Screams heard from the deep .DOLLAR pit at nearby St. Jean Vianney when the slide began Tuesday night helped guide rescue moneyIV crisisworkers to the victims. About and Europe's 70 of them were rescued. But yesterday there was si- lcnce, and access to the dis- FRANKFURT, Germany (AP/ aster area---a hole about 700 AFRTS)--Massive selling of feet wide, over 100- feet deep the dollar forced several and about a half-mile long--- government banks of Europe was complicated by sliding mud to stop buying American and rising waters. currency yesterday and It was the third serious sent money experts into landslide in the area in five consultations on ways to months. check Europe's growing The cave-in swept 35 homes, monetary crisis. -

Film Noir Database

www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) Film Noir Database This database has been created by author, P.S. Marshall, who has watched every single one of the movies below. The latest update of the database will be available on my website: www.kingofthepeds.com The following abbreviations are added after the titles and year of some movies: AFN – Alternative/Associated to/Noirish Film Noir BFN – British Film Noir COL – Film Noir in colour FFN – French Film Noir NN – Neo Noir PFN – Polish Film Noir www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) TITLE DIRECTOR Actor 1 Actor 2 Actor 3 Actor 4 13 East Street (1952) AFN ROBERT S. BAKER Patrick Holt, Sandra Dorne Sonia Holm Robert Ayres 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) HENRY HATHAWAY James Cagney Annabella Richard Conte Frank Latimore 36 Hours (1953) BFN MONTGOMERY TULLY Dan Duryea Elsie Albiin Gudrun Ure Eric Pohlmann 5 Against the House (1955) PHIL KARLSON Guy Madison Kim Novak Brian Keith Alvy Moore 5 Steps to Danger (1957) HENRY S. KESLER Ruth Ronan Sterling Hayden Werner Kemperer Richard Gaines 711 Ocean Drive (1950) JOSEPH M. NEWMAN Edmond O'Brien Joanne Dru Otto Kruger Barry Kelley 99 River Street (1953) PHIL KARLSON John Payne Evelyn Keyes Brad Dexter Frank Faylen A Blueprint for Murder (1953) ANDREW L. STONE Joseph Cotten Jean Peters Gary Merrill Catherine McLeod A Bullet for Joey (1955) LEWIS ALLEN Edward G. Robinson George Raft Audrey Totter George Dolenz A Bullet is Waiting (1954) COL JOHN FARROW Rory Calhoun Jean Simmons Stephen McNally Brian Aherne A Cry in the Night (1956) FRANK TUTTLE Edmond O'Brien Brian Donlevy Natalie Wood Raymond Burr A Dangerous Profession (1949) TED TETZLAFF George Raft Ella Raines Pat O'Brien Bill Williams A Double Life (1947) GEORGE CUKOR Ronald Colman Edmond O'Brien Signe Hasso Shelley Winters A Kiss Before Dying (1956) COL GERD OSWALD Robert Wagner Jeffrey Hunter Virginia Leith Joanne Woodward A Lady Without Passport (1950) JOSEPH H.