Art of Orient 2015.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title "Music for a National Defense": Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7209v5n2 Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(13) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Howard, Joshua H. Publication Date 2014-12-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Music for a National Defense”: Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Joshua H. Howard, University of Mississippi Abstract This article examines the popularization of “mass songs” among Chinese Communist troops during the Anti-Japanese War by highlighting the urban origins of the National Salvation Song Movement and the key role it played in bringing songs to the war front. The diffusion of a new genre of march songs pioneered by Nie Er was facilitated by compositional devices that reinforced the ideological message of the lyrics, and by the National Salvation Song Movement. By the mid-1930s, this grassroots movement, led by Liu Liangmo, converged with the tail end of the proletarian arts movement that sought to popularize mass art and create a “music for national defense.” Once the war broke out, both Nationalists and Communists provided organizational support for the song movement by sponsoring war zone service corps and mobile theatrical troupes that served as conduits for musicians to propagate their art in the hinterland. By the late 1930s, as the United Front unraveled, a majority of musicians involved in the National Salvation Song Movement moved to the Communist base areas. Their work for the New Fourth Route and Eighth Route Armies, along with Communist propaganda organizations, enabled their songs to spread throughout the ranks. -

Read the Introduction

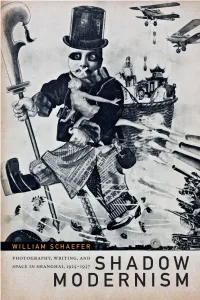

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

MANHUA MODERNITY HINESE CUL Manhua Helped Defi Ne China’S Modern Experience

CRESPI MEDIA STUDIES | ASIAN STUDIES From fashion sketches of Shanghai dandies in the 1920s, to phantasma- goric imagery of war in the 1930s and 1940s, to panoramic pictures of anti- American propaganda rallies in the 1950s, the cartoon-style art known as MODERNITY MANHUA HINESE CUL manhua helped defi ne China’s modern experience. Manhua Modernity C TU RE o ers a richly illustrated and deeply contextualized analysis of these il- A lustrations from the lively pages of popular pictorial magazines that enter- N UA D tained, informed, and mobilized a nation through a half century of political H M T and cultural transformation. N H O E A “An innovative reconceptualization of manhua. John Crespi’s meticulous P study shows the many benefi ts of interpreting Chinese comics and other D I M C illustrations not simply as image genres but rather as part of a larger print E T culture institution. A must-read for anyone interested in modern Chinese O visual culture.” R R I CHRISTOPHER REA, author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History A of Laughter in China L N “A rich media-centered reading of Chinese comics from the mid-1920s T U U I I through the 1950s, Manhua Modernity shifts the emphasis away from I R R T T ideological interpretation and demonstrates that the pictorial turn requires T N N examinations of manhua in its heterogenous, expansive, spontaneous, CHINESE CULTURE AND THE PICTORIAL TURN AND THE PICTORIAL CHINESE CULTURE Y and interactive ways of engaging its audience’s varied experiences of Y fast-changing everyday life.” YINGJIN ZHANG, author of Cinema, Space, and Polylocality in a Globalizing China JOHN A. -

Poster Art of Modern China 26-28 June 2014

POSTER ART OF MODERN CHINA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE 26-28 JUNE 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH POSTER ART OF MODERN CHINA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE CONTENTS Pages 2-3 Schedule Pages 4-13 Paper Abstracts PARTICIPANTS Julia Andrews Ohio State University Katharine Burnett University of California, Davis Chen Ruilin Tsinghua University Joachim Gentz University of Edinburgh Natascha Gentz University of Edinburgh Christoph Harbsmeier University of Oslo Denise Ho Chinese University of Hong Kong Huang Xuelei University of Edinburgh Richard King University of Victoria Kevin McLoughlin National Museum of Scotland Paul Pickowicz University of California, San Diego Yang Chia-ling University of Edinburgh Yang Peiming Shanghai Propaganda Art Center Zheng Ji University of Edinburgh 1 POSTER ART OF MODERN CHINA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE Friday 27th June 2014 09.30-11.15 Session 1 – Welcome and Keynote Speeches 09.30-09.45 Welcome address Chris Breward, Principal, Edinburgh College of Art Introduction, Natascha Gentz 09.45-10.30 Chen Ruilin, Tsinghua University 百年变迁: 从商业月份牌画到政治宣传画 10.30-11.15 Yang Peiming, Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Museum Ha Qiongwen, the Master Chinese Propaganda Poster Artist 11.15-11.30 Tea/ Coffee 11.30-13.00 Session 2 - Chair: Paul Pickowicz 11.30-12.15 Joachim Gentz, University of Edinburgh Ambiguity of Religious Signs and Claim to Power in Chinese Propaganda Posters 12.15-13.00 Christoph Harbsmeier, University of Oslo The Cartoonist Feng Zikai (1898 - 1975) 14.00-13.45 Lunch 15.00-16.30 Session 3 - Chair: Richard King 15.00-15.45 -

Ink and Tears: Memory, Mourning, and Writing in the Yu Family Rania Huntington

University of Hawai'i Manoa Kahualike UH Press Book Previews University of Hawai`i Press Fall 8-31-2018 Ink and Tears: Memory, Mourning, and Writing in the Yu Family Rania Huntington Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/uhpbr Part of the Asian History Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Huntington, Rania, "Ink and Tears: Memory, Mourning, and Writing in the Yu Family" (2018). UH Press Book Previews. 14. https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/uhpbr/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in UH Press Book Previews by an authorized administrator of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ink and Tears MEMORY, MOURNING, and WRITING in the YU FAMILY RANIA HUNTINGTON INK AND TEARS INK AND TEARS Memory, Mourning, and Writing in the Yu Family Rania Huntington UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I PRESS HONOLULU © 2018 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 23 22 21 20 19 18 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Huntington, Rania, author. Title: Ink and tears : memory, mourning, and writing in the Yu family / Rania Huntington. Description: Honolulu : University of Hawai‘i Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018004209 | ISBN 9780824867096 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Yu family. | Yu, Yue, 1821-1906. | Yu, Pingbo, 1900–1990. | Authors, Chinese—Biography. Classification: LCC PL2734.Z5 H86 2018 | DDC 895.18/4809—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004209 Cover art: Feng Zikai, Plum Tree and Railings, from Yu Pingbo, Yi (repr., Hangzhou, 2004), poem 14. -

A Study of Feng Zikai's Prose from the Perspective of Modernity

2017 3rd International Conference on Management Science and Innovative Education (MSIE 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-488-2 A Study of Feng Zikai's Prose from the Perspective of Modernity CHUNXIAO LI ABSTRACT Feng Zikai who has an important influence on the creation of Chinese new literature is the master of modern prose creation. His prose is winding and fresh, focusing on the description of people and things in daily life as well as views of life and world. His words are elegant and pure. Several pieces of his prose have been incorporated into the primary school textbooks. He had become a famous modern writer. This thesis studies Feng Zikai's prose in the light of new literature and modernist literature. From the perspective of the content, structure and central idea of his prose, the author comments on his works according to the related modernity viewpoint, aiming to provide the reference material for the research on Feng Zikai's prose. KEYWORDS Feng Zikai; prose; modernity INTRODUCTION Prose is a kind of literary genre that mainly expresses the actual life, knowledge and experience of the writer and also contains the writer's true feelings and related thoughts. The length of the prose is flexible but most of proses are short. As a master of modern prose, Feng Zikai has a unique style in prose creation. Affected by the Western documentary literature, the style of his works is featured by short-length, beautiful, vivid and interesting expressions. In recent years, the study of Feng Zikai's prose has become another major research field after his painting. -

Feng Zikai's Experience of War As Seen in a Teacher's Diary

Feng Zikai’s Experience of War as Seen in A Teacher’s Diary 著者 ONO Kimika journal or Toyohogaku publication title volume 57 number 3 page range 27(442)-46(423) year 2014-03-31 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1060/00006498/ Creative Commons : 表示 - 非営利 - 改変禁止 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.ja 東洋法学 第57巻第 3 号(2014年 3 月) 27 《 論 説 》 Feng Zikaiʼs Experience of War as Seen in A Teacher’s Diary( 1 ) ONO, Kimika Feng Zikai in Wartime Feng Zikai 豊子愷( 1898-1975) was a multitalented Chinese artist who was part of the liberal environment of his time. Amongst his various activities he is particularly well-known for his distinctive style of illustration as shown in his 1925 collection ( 2 ) called Zikai’s Cartoons and for his essays collected in 1931 under the name of Es- ( 3 ) says from the Yuanyuan Studio . Following the appearance of these works, where philosophical ideas were woven into themes that included children( Figure 1 ), classi- cal poetry( Figure 2 ) and scenes from daily life( Figure 3 ), he gained great popularity ( 4 ) among the new class of urban intellectuals . Following the Manchurian Incident of 1931, Chinese literary circles enthusiastical- ly discussed forming a united popular front against Japanese aggression. Feng was a member of the Chinese Writersʼ Association, formed in Shanghai in June 1936, and sup- ported the “Declaration on Uniting to Resist ( 5 ) Aggression and on Freedom of Speech ,” (Figure 1) Feng Zikai, “A-Bao Has adopted in October the same year. Two Legs, Chair Has Four The invasion of Shanghai by the Japanese Legs” (442) 28 Feng Zikai’s Experience of War as Seen in A Teacher’s Diary〔Kimika ONO〕 (Figure 2) Feng Zikai, “Season of (Figure 3) Feng Zikai, “Sweat” Fresh Cherry and Green Musa Basjoo” army in the summer of 1937 brought all-out war. -

Books of Abstracts

International Conference, Université de Mons 4 May 1919: History in Motion – A Political, Social and Cultural Look at a Turning Point in the History of Modern China BOOKS OF ABSTRACTS Keynote speakers Joan JUDGE (York University, Canada) “The Other Vernacular: Commoner Knowledge Culture Circa 1919” Lu Xun 魯迅 (1881-1936) wrote with characteristic clarity and bite in 1919 that nothing was straightforward in the May Fourth era: “All things have two, three, or multiple layers and every layer has its own selF-contradictions.” While he was referring to divisions within academic culture, Lu Xun’s observation is even more apt when we examine the layers of complexity that extended beyond it. This paper examines two oF the most intractable “multi-layered” problems that Lu Xun and his cohort grappled with—how to deal with “the people” and how to Formulate a new vernacular language—from another vantage point. Its source base is not New Culture journals but various genres of cheap print. Its protagonists are not intellectuals but common readers, editorial entrepreneurs, and those I call “forward- looking mundane traditionalists.” For these individuals, May Fourth was not a watershed but just another twist in the road: a moment that was relevant to the extent that it affected the kinds of information common readers needed and the Form in which it could most efFectively be delivered. My Focus is on the Guangyi shuju 廣益書局 (“Kwang Yih Book Co. Ltd”) which continuously produced cheap print and a certain register of vernacular knowledge in the decades both preceding and Following 1919. I speciFically examine one of Guangyi’s publications that obliquely but productively addresses the question of the new vernacular: the Suyu dian 《俗語典》 (Dictionary of common sayings) published in 1922. -

1 the Pictorial Turn and China's Manhua Modernity, 1925-19601

The Pictorial Turn and China’s Manhua Modernity, 1925-19601 John A. Crespi Defining manhua—usually translated as “caricature” or “cartoon”—is like trying to put spilled ink back into the bottle. The word should be warning enough. Where the second character for the second syllable, hua, refers to pictorial art in general, the first character, man, connotes several situations: a state of overflow and inundation, an attitude of freedom and casualness, and, most broadly, a general feeling of being all over the place. The challenge of this book—The Pictorial Turn and China’s Manhua Modernity, 1925-1960—is to embrace the chaos, while also making sense of it. This is not, of course, the first study of manhua. Many have attempted to tidy up its mess. As a general rule, this has been done via narrative: stories that contribute to making manhua out to be a stable and readily categorizable “thing,” or in more formal terms, a discursive object, that can be interrogated to give us various kinds of data, historical, biographical, etc. A ready example is the narrative of origins, a nativist pictorial lineage for manhua fabricated from the history of China’s arts by selecting items that seem to resonate with a current definition of manhua, such as simplification, exaggeration, and satirical intent. That approach can, with imagination, create a story of specifically Chinese manhua art beginning 8000 years ago with patterns on Neolithic Banpo pottery.2 The need to tell this kind of tale comes in part from the cultural-nationalist desire for myths of deep beginnings, and in part from the desire to construct a discrete, researchable, category of pictorial art. -

The Writer's Art: Tao Yuanqing and the Formation of Modern Chinese Design (1900-1930)

The Writer's Art: Tao Yuanqing and the Formation of Modern Chinese Design (1900-1930) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ren, Wei. 2015. The Writer's Art: Tao Yuanqing and the Formation of Modern Chinese Design (1900-1930). Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17465116 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Writer’s Art: Tao Yuanqing and the Formation of Modern Chinese Design (1900-1930) A dissertation presented by Ren, Wei to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2015 © 2015 Ren,Wei All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Eugene Y. Wang Ren, Wei The Writer’s Art: Tao Yuanqing and the Formation of Modern Chinese Design (1900-1930) Abstract The dissertation examines the history of modern design in early 20th-century China. The emergent field of design looked to replace the specific cultural and historical references of visual art with an international language of geometry and abstraction. However, design practices also, encouraged extracting culturally unique visual forms by looking inward at a nation’s constructed past. -

CHILDREN's LITERATURE in CHINA, 1920S-1960S By

FROM LU XUN’S “SAVE THE CHILDREN” TO MAO’S “THE WORLD IS YOURS”: CHILDREN’S LITERATURE IN CHINA, 1920s-1960s by Evgenia Stroganova B.A., St. Petersburg State University, 2010 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2014 © Evgenia Stroganova, 2014 Abstract In 1929 the leading Chinese intellectual Hu Shi said: “To understand the degree to which a particular culture is civilized, we must appraise … how it handles its children.”1 In 1957, Chairman Mao told Chinese youth that “both the world and China’s future belonged to them.”2 In both eras, cultural leaders placed children and youth in the centre of cultural and political discourse associating them with the nation’s future. This thesis compares Chinese children’s literature during the Republican period (1912-1949) and the early People’s Republic of 1949- 1966, until the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and argues that children’s writers who worked in both new Chinas treated youth and children as key agents in building a nation-state. In this thesis, I focus on the works of three prominent writers, Ye Shengtao (1894-1988), Bing Xin (1900-1999) and Zhang Tianyi (1906-1985) who wrote children’s literature and were prominent cultural figures in both eras. Their writing careers make for excellent case studies in how children’s literature changed from one political era to another. I conduct thematic and stylistic textual analysis of their works and read them against their historical and cultural backgrounds to determine how children’s writings changed and why. -

Representations of Children in the Work of the Cartoon Propaganda Corps During the Second Sino-Japanese War

“Chinese Children Rise Up!”: Representations of Children in the Work of the Cartoon Propaganda Corps during the Second Sino-Japanese War Laura Pozzi, European University Institute Abstract During the War of Resistance against Japan (1937–1945), children were a major subject of propaganda images. Children had become significant figures in China when May Fourth intellectuals, influenced by evolutionary thinking, deemed “the child” as a central figure for the modernization of the country. Consequently, during the war, cartoonists employed already- established representations of children for propagandistic purposes. By analyzing images published by members of the Cartoon Propaganda Corps in the wartime magazine Resistance Cartoons, this article shows how portrayals of children fulfilled symbolic as well as normative functions. These images provide us with information about the symbolic power of representations of children, and about authorities’ expectations of China’s youngest citizens. However, cartoonists also created images undermining the heroic rhetoric often attached to representations of children, especially after the dismissal of the Cartoon Propaganda Corps in 1940. This was the case with cartoonist Zhang Leping’s (1910–1992) sketches of “Zhuji after the Devastation,” which revealed the discrepancies between propagandistic representations and children’s everyday life in wartime China. Keywords: Second Sino-Japanese War, War of Resistance, history of childhood, cartoons, propaganda, Cartoon Propaganda Corps, Zhang Leping Introduction Who killed your parents? Who killed your sisters? Who pierced our brothers with a bayonet? Who seized our lands and properties? We should go and fight against them! Old people, middle-aged people, young people, it’s time to rise up! You little masters of the New China, rise up! Sing on the street corners, put a play on the stage, transport the wounded from the battlefield, display posters on whitewashed walls.