Books of Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imagining Sisterhood in Modern Chinese Texts, 1890–1937

Imagining Sisterhood in Modern Chinese Texts, 1890–1937 Imagining Sisterhood in Modern Chinese Texts, 1890–1937 Yun Zhu LEXINGTON BOOKS Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Lexington Books An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2017 by Lexington Books All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available ISBN 978-1-4985-3629-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4985-3630-1 (electronic) TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America Table of Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: Gender, Nation, Subjectivities, and the Discourse on Sisterhood in Modern China ix 1 The Emergence of the “Women’s Sphere” and the Promotion of Sisterhood in the Late Qing 1 2 From Dual Slaves to Liberty Flowers: The Feminist-Nationalist Spectrum of Sisterhood in Stones of the Jingwei Bird and Chivalric Beauties 35 3 Is Blood Always Thicker than Water?: Rival Sisters and the Tensions of Modernity 73 4 Cosmopolitan Bourgeois Sisterhood and the Ambiguities of Female-Centeredness in Lin Loon Magazine (1931–1937) 113 5 Sisterly Lovers in Women’s Fiction and the Potential of “Nondevelopment” as a Feminist Intervention 149 Conclusion 183 Bibliography 187 Index 205 About the Author 217 v Acknowledgments This book has been developed from my PhD dissertation, which I completed in 2012 at the University of South Carolina. -

Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 489 SO 025 360 AUTHOR Yu-ning, Li, Ed. TITLE Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM Johnson & Associates, 257 East South St., Franklin, IN 46131-2422 (paperback: $25; clothbound: ISBN-1-880938-008, $39; shipping: $3 first copy, $0.50 each additional copy). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chinese Culture; *Cultural Images; Females; Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Legends; Mythology; Role Perception; Sexism in Language; Sex Role; *Sex Stereotypes; Sexual Identity; *Womens Studies; World History; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Asian Culture; China; '`Chinese Literature ABSTRACT This book examines the ways in which Chinese literature offers a vast array of prospects, new interpretations, new fields of study, and new themes for the study of women. As a result of the global movement toward greater recognition of gender equality and human dignity, the study of women as portrayed in Chinese literature has a long and rich history. A single volume cannot cover the enormous field but offers volume is a starting point for further research. Several renowned Chinese writers and researchers contributed to the book. The volume includes the following: (1) Introduction (Li Yu- Wing);(2) Concepts of Redemption and Fall through Woman as Reflected in Chinese Literature (Tsung Su);(3) The Poems of Li Qingzhao (1084-1141) (Kai-yu Hsu); (4) Images of Women in Yuan Drama (Fan Pen Chen);(5) The Vanguards--The Truncated Stage (The Women of Lu Yin, Bing Xin, and Ding Ling) (Liu Nienling); (6) New Woman vs. -

News Release

Research Express@NCKU - News Release Research Express@NCKU Volume 22 Issue 8 - July 20, 2012 [ http://research.ncku.edu.tw/re/news/e/20120720/1.html ] NCKU touts efforts to preserve cultural heritage on campus NCKU Press Center [Tainan, Taiwan, 3 July 2012] National Cheng Kung University (NCKU), southern Taiwan, held a news press conference in Taipei June 28 to share the school’s historical treasures and to call for joint efforts among educational institutes nationwide to preserve cultural heritage on campus. Dr. Hong-Sen Yan, vice president of NCKU, hosted the conference, in which he shared his experience in planning and preserving NCKU’s historical heritage. A university should identify its distinctive characteristic and grow with it to achieve excellence in education, said Dr. Yan, adding that it takes time and effort to keep the artifacts with historical significance. Dr. Kuang-Nan Huang, minister without portfolio of the Executive Yuan, Academician Ovid Tzeng of Academia Sinica, and Mr. Chen-Yu Nien, deputy director of Bureau of Cultural Heritage, Ministry of Culture, were present at the conference on behalf of their organizations. They praised NCKU for its resolution and dedication to preserving the school’s historical assets. Many world-renowned universities have their archives to keep the non-current records of the university, allowing the tradition and the spirit to pass down, according to Tzeng, who said NCKU’s aspiration to enlighten the students with the historical heritage is admirable. Dr. Huang emphasized the importance of time and resources in promoting cultural heritage. He noted that people are the key elements of culture assets. -

Tracing Confucianism in Contemporary China

TRACING CONFUCIANISM IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA Ruichang Wang and Ruiping Fan Abstract: With the reform and opening policy implemented by the Chinese government since the late 1970s, mainland China has witnessed a sustained resurgence of Confucianism first in academic studies and then in social practices. This essay traces the development of this resurgence and demonstrates how the essential elements and authentic moral and intellectual resources of long-standing Confucian culture have been recovered in scholarly concerns, ordinary ideas, and everyday life activities. We first introduce how the Modern New Confucianism reappeared in mainland China in the three groups of the Chinese scholars in the Confucian studies in the 1980s and early 1990s. Then we describe how a group of innovative mainland Confucian thinkers has since the mid-1990s come of age launching new versions of Confucian thought differing from that of the overseas New Confucians and their forefathers, followed by our summary of public Confucian pursuits and activities in the mainland society in the recent decade. Finally, we provide a few concluding remarks about the difficulties encountered in the Confucian development and our general expectations for future. 1 Introduction Confucianism is not just a philosophical doctrine constructed by Confucius (551- 479BCE) and developed by his followers. It is more like a religion in the general sense. In fact, Confucius took himself as a cultural transmitter rather than a creator (cf. Analects 7.1, 7.20), inheriting the Sinic culture that had long existed before him.2 Dr. RUICHANG WANG, Professor, School of Culture & Communications, Capital university of Economics and Business. Emai: [email protected]. -

This Is the Accepted Version of a Forthcoming Book Review That Will Be Published in Bulletin of the School of Oriental and Afric

This is the accepted version of a forthcoming book review that will be published in Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies by Cambridge University Press: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bulletin-of-the-school-of-oriental-and-african-studies/all- issues Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/24718/ BARBARA HOSTER: Konversion zum Christentum in der modernen chinesischen Literatur: Su Xuelins Roman Jixin (Dornenherz, 1929). (Deutsche Ostasienstudien 29.) vi, 322 pp. Gossenberg: OSTASIEN Verlag, 2017. € 35.80. ISBN 978-3- 946114-30-7. Lars Laamann, Department of History, School of History, Religions and Philosophies, SOAS University of London Conversion to Christianity. A powerful concept which, in the case of China’s modern history, evokes the most controversial reactions, ranging from intercultural exchange to the imposition of alien concepts and the outright imposition of colonial superstructures. Barbara Hoster’s doctoral research topic is, however, of a distinctly different nature. Rather than analysing the impact of Western missions overseas, Hoster dissects the mind of a young woman, who had arrived during the 1920s in France as a student and whose profuse writings focused on the encounter of different cultural, political and not least gender-related discourses in the shape of people who became part of the young author’s life. “Conversion to Christianity in modern Chinese literature: Su Xuelin’s novel Jixin (Heart of Thorns, 1929)” thus describes the tribulations of a young woman who felt at odds with the ‘progressive’ winds which were sweeping the intellectual landscape of the 1920s, and who reacted by seeking solace in the spiritual world which she encountered during her sojourn at the Institut Franco-Chinois in Lyon during the early 1920s. -

Nora's Performance in China

Nora’s Performance in China (1914-2010): Inspiration, Communities and Political Theatre By Xiaofei Chen Master thesis Center for Ibsen Studies UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Spring semester, 2010 Acknowledgements I came to Oslo University by serendipity. When I was searching the resources for my thesis Nora’s rewriting in China(1914-1948), by accident the website of Ibsen Center jumped out. Then I came to Norway and studied at Ibsen Center. Whether in Norway or in China, many people asked me why I had chosen Ibsen studies and had come to Norway. I always said because I liked Ibsen’s plays and Norway has an Ibsen Center. It turned out that I had chosen correctly. At the Ibsen Center, professors and students from all over the world gave me lots of chances to access different ideas and insights into Ibsen studies, especially from theatre and performance aspects. I could access the original Ibsen’s texts and understand Norwegian society in Ibsen’s times, and I could watch Ibsen’s performances from different countries either in the National Theatre or through DVDs in class. Thanks to Ibsen Center for giving me the opportunity to study here, and I also want to show my appreciation for all the professors at the Ibsen Center: especially Frode Helland, Astrid Sæther, Jon Nygaard, Atle Kittang, Erika Fischer-Lichte and Nilu Kamaluddin, Julie Holledge, Knut Brynhildsvoll, who gave me the latest information about Ibsen studies through lectures and seminars. My special thanks for my professor, Jon Nygaard, who gave me the inspiration to write this topic with fresh insight. -

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title "Music for a National Defense": Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7209v5n2 Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(13) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Howard, Joshua H. Publication Date 2014-12-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Music for a National Defense”: Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Joshua H. Howard, University of Mississippi Abstract This article examines the popularization of “mass songs” among Chinese Communist troops during the Anti-Japanese War by highlighting the urban origins of the National Salvation Song Movement and the key role it played in bringing songs to the war front. The diffusion of a new genre of march songs pioneered by Nie Er was facilitated by compositional devices that reinforced the ideological message of the lyrics, and by the National Salvation Song Movement. By the mid-1930s, this grassroots movement, led by Liu Liangmo, converged with the tail end of the proletarian arts movement that sought to popularize mass art and create a “music for national defense.” Once the war broke out, both Nationalists and Communists provided organizational support for the song movement by sponsoring war zone service corps and mobile theatrical troupes that served as conduits for musicians to propagate their art in the hinterland. By the late 1930s, as the United Front unraveled, a majority of musicians involved in the National Salvation Song Movement moved to the Communist base areas. Their work for the New Fourth Route and Eighth Route Armies, along with Communist propaganda organizations, enabled their songs to spread throughout the ranks. -

Read the Introduction

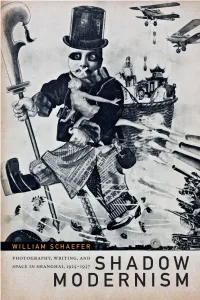

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

A Thematic Study of Lh Xun's Prose P O E T R Y Collection

A THEMATIC STUDY OF LH XUN'S PROSE POETRY COLLECTION WILD GRASS by TIANM1NG LI M.A., The University of Ilcnan, 1086 M.A., The University of British Columbia, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Asian Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the rexiuired standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 1998 © Tianming Li, 1998 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) tt Abstract This thesis is a comprehensive thematic study of the unique prose poetry collection Wild Grass by the famous modern Chinese writer Lu Xun. It provides a general survey of previous Wild Grass studies both in China and abroad in the past 70 years in Chapter 1. The survey clarifies the achievements and defects of those studies, and finds that they are still insufficient and can and should be further expanded. By employing a comprehensive methodology, including close reading, rhetorical analysis, intertextual interpretation, and some standard psychoanalytic insights, the thesis explores the themes of Wild Grass on three different levels. -

MANHUA MODERNITY HINESE CUL Manhua Helped Defi Ne China’S Modern Experience

CRESPI MEDIA STUDIES | ASIAN STUDIES From fashion sketches of Shanghai dandies in the 1920s, to phantasma- goric imagery of war in the 1930s and 1940s, to panoramic pictures of anti- American propaganda rallies in the 1950s, the cartoon-style art known as MODERNITY MANHUA HINESE CUL manhua helped defi ne China’s modern experience. Manhua Modernity C TU RE o ers a richly illustrated and deeply contextualized analysis of these il- A lustrations from the lively pages of popular pictorial magazines that enter- N UA D tained, informed, and mobilized a nation through a half century of political H M T and cultural transformation. N H O E A “An innovative reconceptualization of manhua. John Crespi’s meticulous P study shows the many benefi ts of interpreting Chinese comics and other D I M C illustrations not simply as image genres but rather as part of a larger print E T culture institution. A must-read for anyone interested in modern Chinese O visual culture.” R R I CHRISTOPHER REA, author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History A of Laughter in China L N “A rich media-centered reading of Chinese comics from the mid-1920s T U U I I through the 1950s, Manhua Modernity shifts the emphasis away from I R R T T ideological interpretation and demonstrates that the pictorial turn requires T N N examinations of manhua in its heterogenous, expansive, spontaneous, CHINESE CULTURE AND THE PICTORIAL TURN AND THE PICTORIAL CHINESE CULTURE Y and interactive ways of engaging its audience’s varied experiences of Y fast-changing everyday life.” YINGJIN ZHANG, author of Cinema, Space, and Polylocality in a Globalizing China JOHN A. -

Blanka Nyirádi the Birth of Chinese Tragedy: the Tragic Clash Of

Blanka Nyirádi The Birth of Chinese Tragedy: the Tragic Clash of Gender Roles in Cao Yu’s Thunderstorm Doctoral Dissertation THESES Eötvös Loránd University of Sciences Faculty of Humanities Doctoral School of Linguistics Budapest, 2019 1 I. Theme and objective of research The main scope of research of the present dissertation is the 20th-century development of modern Chinese drama, the huaju 话剧 and one of its representative dramatic pieces. In this historic period, China was subject to revolutionary changes (mostly enforced in the beginning), resulting in the substantial transformation of its society and culture. The wild enthusiasm that affected and saw these changes through created a nation-wide positive initiative, and thus promoted a substantive discourse on a series of important social and cultural issues. Changes by definition carry contradiction. Next to progress, there is always the difficulty of breaking away from the old and familiar, and the controversial state of mind that inevitably accompanies this process. The diverse manifestations of this duality that surface in the literary works of the era enrich them with a special complexity. An outstanding achievement of this period is the ’promotion’ of theatre. The art of traditional Chinese theatre is a unique, complex and invaluable cultural heritage, which, in spite of the temporary dominance of this 20th-century new form, thrives on. The modern dramatic art and play is a special direction of development in the history of Chinese drama that was the result of the impact Western dramatic traditions made on Chinese ones. This reform of theatre and drama was purely the demand of the time. -

Poster Art of Modern China 26-28 June 2014

POSTER ART OF MODERN CHINA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE 26-28 JUNE 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH POSTER ART OF MODERN CHINA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE CONTENTS Pages 2-3 Schedule Pages 4-13 Paper Abstracts PARTICIPANTS Julia Andrews Ohio State University Katharine Burnett University of California, Davis Chen Ruilin Tsinghua University Joachim Gentz University of Edinburgh Natascha Gentz University of Edinburgh Christoph Harbsmeier University of Oslo Denise Ho Chinese University of Hong Kong Huang Xuelei University of Edinburgh Richard King University of Victoria Kevin McLoughlin National Museum of Scotland Paul Pickowicz University of California, San Diego Yang Chia-ling University of Edinburgh Yang Peiming Shanghai Propaganda Art Center Zheng Ji University of Edinburgh 1 POSTER ART OF MODERN CHINA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE Friday 27th June 2014 09.30-11.15 Session 1 – Welcome and Keynote Speeches 09.30-09.45 Welcome address Chris Breward, Principal, Edinburgh College of Art Introduction, Natascha Gentz 09.45-10.30 Chen Ruilin, Tsinghua University 百年变迁: 从商业月份牌画到政治宣传画 10.30-11.15 Yang Peiming, Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Museum Ha Qiongwen, the Master Chinese Propaganda Poster Artist 11.15-11.30 Tea/ Coffee 11.30-13.00 Session 2 - Chair: Paul Pickowicz 11.30-12.15 Joachim Gentz, University of Edinburgh Ambiguity of Religious Signs and Claim to Power in Chinese Propaganda Posters 12.15-13.00 Christoph Harbsmeier, University of Oslo The Cartoonist Feng Zikai (1898 - 1975) 14.00-13.45 Lunch 15.00-16.30 Session 3 - Chair: Richard King 15.00-15.45