The Child According to Feng Zikai Marie Laureillard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PROSE of ZHU ZIQING by IAIN WILLIAM CROFTS B.A., The

THE PROSE OF ZHU ZIQING by IAIN WILLIAM CROFTS B.A., The University of Leeds, 1980 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF ASIAN STUDIES We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May 1984 (© Iain William Crofts, 1984 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of W tSTJiplZS The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date £1 MllSf /W ABSTRACT Zhu Ziqing was a Chinese academic who developed a reputation first as a poet and later as an essayist in the 1920's and 1930's. His works are still read widely in China and are considered important enough to be included in the curriculum of secondary schools and universities in the People's Republic of China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Despite his enduring reputation among his countrymen, he is little known abroad and Western scholarly works on modern Chinese literature scarcely mention him. This thesis examines Zhu Ziqing's prose, since it is his essays which are the basis of his reputation. -

Analysis of Language Features of Zhang Peiji's Translated Version Of

http://wjel.sciedupress.com World Journal of English Language Vol. 6, No. 2; 2016 Analysis of Language Features of Zhang Peiji’s Translated Version of The Sight of Father’s Back Written by Zhu Ziqing Jianjun Wang1,* & Yixuan Guo1 1College of Foreign Languages, Inner Mongolia University, Hohhot, China *Correspondence: College of Foreign Languages, Inner Mongolia University, 24 Zhaojun Road, Yuquan District, Hohhot 010070, P. R. China. Tel: 86-471-499-3241. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 22, 2016 Accepted: May 12, 2016 Online Published: May 29, 2016 doi:10.5430/wjel.v6n2p19 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v6n2p19 Abstract Zhu Ziqing’s The Sight of Father’s Back enjoys high reputation and has been translated into various versions by a lot of translators, including Zhang Peiji, Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang and so on. Concerning all the versions, this paper aims to analyze language features of Zhang Peiji’s translated version of The Sight of Father’s Back. It mainly sets out from language features. It analyzes features of word selection in this translation by some examples which can reflect features very well. This is the way in which the authors conduct this paper. Through this paper, the authors aim to find out different language features of prose translation and thus conclude some experiences for further studies in the related aspect in the future. Keywords: The Sight of Father’s Back; Zhu Ziqing; Zhang Peiji’s translated version; language feature; word selection 1. Introduction Prose writing has had a long history in China. After “The May Fourth Movement” in China, it began to flourish as poetry writing did. -

Analysis on the Translation of Mao Zedong's 2Nd Poem in “送瘟神 'Sòng Wēn Shén'” by Arthur Cooper in the Light O

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 11, No. 8, pp. 910-916, August 2021 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1108.06 Analysis on the Translation of Mao Zedong’s 2nd Poem in “送瘟神 ‘sòng wēn shén’” by Arthur Cooper in the Light of “Three Beauties” Theory Pingli Lei Guangdong Baiyun University, Guangzhou 510450, Guangdong, China Yi Liu Guangdong Baiyun University, Guangzhou 510450, Guangdong, China Abstract—Based on “Three Beauties” theory of Xu Yuanchong, this paper conducts an analysis on Arthur Cooper’s translation of “送瘟神”(2nd poem) from three aspects: the beauty of sense, sound and form, finding that, because of his lack of empathy for the original poem, Cooper fails to convey the connotation of the original poem, the rhythm and the form of the translated poem do not match Chinese classical poetry, with three beauties having not been achieved. Thus, the author proposes that, in order to better spread the culture of Chinese classical poetry and convey China’s core spirit to the world, China should focus on cultivating the domestic talents who have a deep understanding about Chinese culture, who are proficient not only in Chinese classical poetry, but also in classical poetry translation. Index Terms—“Three Beauties” theory, “Song When Shen(2nd poem)” , Arthur Cooper, English translation of Chinese classical poetry I. INTRODUCTION China has a long history in poetry creation, however, the research on poetry translation started very late in China Even in the Tang and Song Dynasties, when poetry writing was popular and when culture was open, there did not appear any relevant translation researches. -

Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies in Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Timothy Robert Clifford University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Clifford, Timothy Robert, "In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2234. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 For more information, please contact [email protected]. In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Abstract The rapid growth of woodblock printing in sixteenth-century China not only transformed wenzhang (“literature”) as a category of knowledge, it also transformed the communities in which knowledge of wenzhang circulated. Twentieth-century scholarship described this event as an expansion of the non-elite reading public coinciding with the ascent of vernacular fiction and performance literature over stagnant classical forms. Because this narrative was designed to serve as a native genealogy for the New Literature Movement, it overlooked the crucial role of guwen (“ancient-style prose,” a term which denoted the everyday style of classical prose used in both preparing for the civil service examinations as well as the social exchange of letters, gravestone inscriptions, and other occasional prose forms among the literati) in early modern literary culture. This dissertation revises that narrative by showing how a diverse range of social actors used anthologies of ancient-style prose to build new forms of literary knowledge and shape new literary publics. -

Research Report Learning to Read Lu Xun, 1918–1923: the Emergence

Research Report Learning to Read Lu Xun, 1918–1923: The Emergence of a Readership* Eva Shan Chou ABSTRACT As the first and still the most prominent writer in modern Chinese literature, Lu Xun (1881–1936) had been the object of extensive attention since well before his death. Little noticed, however, is the anomaly that almost nothing was written about Lu Xun in the first five years of his writing career – only eleven items date from the years 1918–23. This article proposes that the five-year lag shows that time was required to learn to read his fiction, a task that necessitated interpretation by insiders, and that further time was required for the creation of a literary world that would respond in the form of published comments. Such an account of the development of his standing has larger applicability to issues relating to the emerg- ence of a modern readership for the New Literature of the May Fourth generation, and it draws attention to the earliest years of that literature. Lu Xun’s case represents the earliest instance of a fast-evolving relationship being created between writers and their society in those years. In 1918, Lu Xun’s “Kuangren riji” (“Diary of a madman”) was published in the magazine Xin qingnian (New Youth).1 In this story, through the delusions of a madman who thought people were plotting to devour other people, the reader is brought to see the metaphorical cannibalism that governed Chinese society and tradition. It was a startling piece of writing, unprecedented in many respects: its use of the vernacular, its unbroken first person narration, its consistent fiction of madness, and, of course, its damning thesis. -

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title "Music for a National Defense": Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7209v5n2 Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(13) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Howard, Joshua H. Publication Date 2014-12-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Music for a National Defense”: Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Joshua H. Howard, University of Mississippi Abstract This article examines the popularization of “mass songs” among Chinese Communist troops during the Anti-Japanese War by highlighting the urban origins of the National Salvation Song Movement and the key role it played in bringing songs to the war front. The diffusion of a new genre of march songs pioneered by Nie Er was facilitated by compositional devices that reinforced the ideological message of the lyrics, and by the National Salvation Song Movement. By the mid-1930s, this grassroots movement, led by Liu Liangmo, converged with the tail end of the proletarian arts movement that sought to popularize mass art and create a “music for national defense.” Once the war broke out, both Nationalists and Communists provided organizational support for the song movement by sponsoring war zone service corps and mobile theatrical troupes that served as conduits for musicians to propagate their art in the hinterland. By the late 1930s, as the United Front unraveled, a majority of musicians involved in the National Salvation Song Movement moved to the Communist base areas. Their work for the New Fourth Route and Eighth Route Armies, along with Communist propaganda organizations, enabled their songs to spread throughout the ranks. -

Read the Introduction

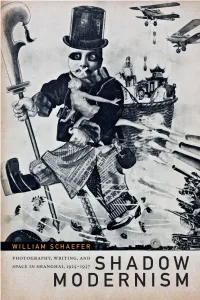

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

MANHUA MODERNITY HINESE CUL Manhua Helped Defi Ne China’S Modern Experience

CRESPI MEDIA STUDIES | ASIAN STUDIES From fashion sketches of Shanghai dandies in the 1920s, to phantasma- goric imagery of war in the 1930s and 1940s, to panoramic pictures of anti- American propaganda rallies in the 1950s, the cartoon-style art known as MODERNITY MANHUA HINESE CUL manhua helped defi ne China’s modern experience. Manhua Modernity C TU RE o ers a richly illustrated and deeply contextualized analysis of these il- A lustrations from the lively pages of popular pictorial magazines that enter- N UA D tained, informed, and mobilized a nation through a half century of political H M T and cultural transformation. N H O E A “An innovative reconceptualization of manhua. John Crespi’s meticulous P study shows the many benefi ts of interpreting Chinese comics and other D I M C illustrations not simply as image genres but rather as part of a larger print E T culture institution. A must-read for anyone interested in modern Chinese O visual culture.” R R I CHRISTOPHER REA, author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History A of Laughter in China L N “A rich media-centered reading of Chinese comics from the mid-1920s T U U I I through the 1950s, Manhua Modernity shifts the emphasis away from I R R T T ideological interpretation and demonstrates that the pictorial turn requires T N N examinations of manhua in its heterogenous, expansive, spontaneous, CHINESE CULTURE AND THE PICTORIAL TURN AND THE PICTORIAL CHINESE CULTURE Y and interactive ways of engaging its audience’s varied experiences of Y fast-changing everyday life.” YINGJIN ZHANG, author of Cinema, Space, and Polylocality in a Globalizing China JOHN A. -

Western Theory and Historical Studies of Chinese Literary Criticism

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 22 (2020) Issue 5 Article 11 Western Theory and Historical Studies of Chinese Literary Criticism Zhirong Zhu East China Normal University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Zhu, Zhirong. -

Poster Art of Modern China 26-28 June 2014

POSTER ART OF MODERN CHINA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE 26-28 JUNE 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH POSTER ART OF MODERN CHINA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE CONTENTS Pages 2-3 Schedule Pages 4-13 Paper Abstracts PARTICIPANTS Julia Andrews Ohio State University Katharine Burnett University of California, Davis Chen Ruilin Tsinghua University Joachim Gentz University of Edinburgh Natascha Gentz University of Edinburgh Christoph Harbsmeier University of Oslo Denise Ho Chinese University of Hong Kong Huang Xuelei University of Edinburgh Richard King University of Victoria Kevin McLoughlin National Museum of Scotland Paul Pickowicz University of California, San Diego Yang Chia-ling University of Edinburgh Yang Peiming Shanghai Propaganda Art Center Zheng Ji University of Edinburgh 1 POSTER ART OF MODERN CHINA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE Friday 27th June 2014 09.30-11.15 Session 1 – Welcome and Keynote Speeches 09.30-09.45 Welcome address Chris Breward, Principal, Edinburgh College of Art Introduction, Natascha Gentz 09.45-10.30 Chen Ruilin, Tsinghua University 百年变迁: 从商业月份牌画到政治宣传画 10.30-11.15 Yang Peiming, Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Museum Ha Qiongwen, the Master Chinese Propaganda Poster Artist 11.15-11.30 Tea/ Coffee 11.30-13.00 Session 2 - Chair: Paul Pickowicz 11.30-12.15 Joachim Gentz, University of Edinburgh Ambiguity of Religious Signs and Claim to Power in Chinese Propaganda Posters 12.15-13.00 Christoph Harbsmeier, University of Oslo The Cartoonist Feng Zikai (1898 - 1975) 14.00-13.45 Lunch 15.00-16.30 Session 3 - Chair: Richard King 15.00-15.45 -

The Gospel According to Marxism: Zhu Weizhi and the Making of Jesus the Proletarian (1950)

religions Article The Gospel According to Marxism: Zhu Weizhi and the Making of Jesus the Proletarian (1950) Zhixi Wang College of Liberal Arts, Shantou University, Shantou 515063, China; [email protected] Received: 31 May 2019; Accepted: 13 September 2019; Published: 19 September 2019 Abstract: This article explores the integration of Marxism into the Gospel narratives of the Christian Bible in Zhu Weizhi’s Jesus the Proletarian (1950). It argues that Zhu in this Chinese Life of Jesus refashioned a Gospel according to Marxism, with a proletarian Jesus at its center, by creatively appropriating a wealth of global sources regarding historical Jesus and primitive Christianity. Zhu’s rewriting of Jesus can be appreciated as a precursor to the later Latin American liberation Christology. Keywords: The Gospel; Marxism; Zhu Weizhi; Jesus the Proletarian; Life of Jesus 1. Introduction In recent decades, scholarly attention has been increasingly paid to Chinese intellectuals’ rewriting in the early twentieth century of the Gospel narratives of the Christian Bible (Ni 2011; Wang 2014, 2017a, 2017b, 2019; Starr 2016; Chin 2018). Among these intellectuals—Zhao Zichen (T. C. Chao, 1888–1979), Wu Leichuan (L. C. Wu, 1870–1944), Zhang Shizhang (Hottinger S. C. Chang, b. 1896), etc.—stands out Zhu Weizhi (W. T. Chu, 1905–1999), who in addition to being first and foremost a preeminent literary scholar, also devoted himself within no more than two years to the recasting of two very different Lives of Jesus, one in 1948 and another 1950. Entitled Yesu jidu (Jesus Christ) and Wuchan zhe yesu zhuan (Jesus the Proletarian) respectively, these two biographies of Jesus (particularly the latter one) have drawn attention from scholars of various disciplinary backgrounds (Gálik 2007; Chin 2015; Liu 2016). -

Ink and Tears: Memory, Mourning, and Writing in the Yu Family Rania Huntington

University of Hawai'i Manoa Kahualike UH Press Book Previews University of Hawai`i Press Fall 8-31-2018 Ink and Tears: Memory, Mourning, and Writing in the Yu Family Rania Huntington Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/uhpbr Part of the Asian History Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Huntington, Rania, "Ink and Tears: Memory, Mourning, and Writing in the Yu Family" (2018). UH Press Book Previews. 14. https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/uhpbr/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in UH Press Book Previews by an authorized administrator of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ink and Tears MEMORY, MOURNING, and WRITING in the YU FAMILY RANIA HUNTINGTON INK AND TEARS INK AND TEARS Memory, Mourning, and Writing in the Yu Family Rania Huntington UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I PRESS HONOLULU © 2018 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 23 22 21 20 19 18 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Huntington, Rania, author. Title: Ink and tears : memory, mourning, and writing in the Yu family / Rania Huntington. Description: Honolulu : University of Hawai‘i Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018004209 | ISBN 9780824867096 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Yu family. | Yu, Yue, 1821-1906. | Yu, Pingbo, 1900–1990. | Authors, Chinese—Biography. Classification: LCC PL2734.Z5 H86 2018 | DDC 895.18/4809—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004209 Cover art: Feng Zikai, Plum Tree and Railings, from Yu Pingbo, Yi (repr., Hangzhou, 2004), poem 14.