Chinese Art 9. the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

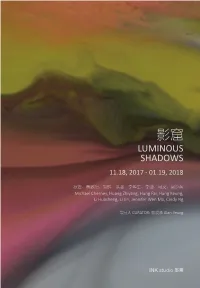

影窟 Luminous Shadows 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018

影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung Contents 006 展览介绍 Introduction 006 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 006 作品 Works 010 006 秋麦 Michael Cherney 010 黄致阳 Huang Zhiyang 026 熊辉 Hung Fai 050 洪强 Hung Keung 076 李华生 Li Huasheng 084 李津 Li Jin 112 马文 Jennifer Wen Ma 150 吴少英 Cindy Ng 158 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Ink Studio. © 2017 Ink Studio Artworks © 1981-2017 The Artists (Front Cover Image 封面图片 ) 吴少英 Cindy NG | Sea of Flowers 花海 (detail 局部 ) | P116 (Back Cover Image 封底图片 ) 李津 Li Jin | The Hungry Tigress 舍身饲虎 (detail 局部 ) | P162 6 7 INTRODUCTION Alan Yeung A painted rock bleeds as living flesh across sheets of paper. A quivering line In Jennifer Wen Ma’s (b. 1970, Beijing) installation, light and glass repeatedly gives form to the nuances of meditative experience. The veiled light of an coalesce into an illusionary landscape before dissolving in a reflective ink icon radiates through the near-instantaneous marks by a pilgrim’s hand. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

City and College Partnerships Between Baden-Württemberg and China

City and College Partnerships between Baden-Württemberg and China City Partnership Collage Partnership Karlsruhe Mannheim Mosbach Stuttgart Zhenjiang (Jiangsu), Qingdao (Shandong) Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University Nanjing (Friendship City) Karlsruher Institute for Technology Mosbach - Suzhou, (Jiangsu): Institute of Technology University Mannheim - Nanjing, (Jiangsu): Southeast University - Peking: Institute of Technology, - Xiamen, (Fujian): Xiamen University Tsinghua University - Shanghai: Tongji University School of Economics & Management, University Stuttgart - Shanghai: Jiao Tong University, Tongji University - Peking: Institute of Technology, East China University of Science and Technology, Central Academy of Fine Arts University of Education Karlsruhe Jiao Tong University, Marbach am Neckar - Shanghai: Jiao Tong University, - Shanghai: East China Normal University Shanghai Advanced Insitute Tongji University Tongling (Provice of Anhui) of Finance, Karlsruhe University for Arts and Design Fudan University State-owned Academy of Visual Art Stuttgart - Peking: Central Academy of Fine Arts - Peking: University of International - Hangzhou, (Zhejiang): China Academy of Art - Wuhan, (Hubei): Huazhong University of Science and Business and Economics, - Shenyang, (Liaoning): Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts Technology, China Academy of Arts Tsinghua University, Heilbronn Peking University Guanghua University of Media Science Stuttgart Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University Stuttgart School of Management University of Heilbronn -

China Daily 0803 D6.Indd

life CHINA DAILY CHINADAILY.COM.CN/LIFE FRIDAY, AUGUST 3, 2012 | PAGE 18 Li Keran bucks market trend The artist has become a favorite at auction and his works are fetching record prices. But overall, the Chinese contemporary art market has cooled, Lin Qi reports in Beijing. i Keran (1907-89) took center and how representative the work is, in addi- stage at the spring sales with tion to the art publications and catalogues it two historic works both cross- has appeared in.” ing the 100 million yuan ($16 Though a record was set by Wan Shan million) threshold. Hong Bian, two other important paintings by His 1974 painting of former Li were unsold, which came as no surprise for Lchairman Mao Zedong’s residence in Sha- art collectors like Yan An. oshan, the revolutionary holy land in Hunan “Both big players and new buyers are bid- province, fetched 124 million yuan at China ding for the best works of the blue-chip art- Guardian, in May. ists, while the market can’t provide as many Th ree weeks later his large-scale blockbust- top-notch artworks and provide the reduced er of 1964, Wan Shan Hong Bian (Th ousands risks that people expect. of Hills in a Crimsoned View), was sold for a “Th is is because in the face of an unclear personal record of 293 million yuan at Poly market, cautious owners would rather keep International Auction. those items, which achieved skyscraping Li, a prominent figure in 20th-century prices, rather than fl ip them at auction,” Yan Chinese art, is recognized for innovating the says. -

Singapore Biennale 2019: Every Step in The

Media Release Singapore Biennale 2019: Every Step In The Right Direction Opens Across Multiple Sites in Singapore on 22 November 2019 77 artists and collectives reflect on contemporary life and the human endeavour for change 20 Nov 2019 - Singapore Biennale 2019 (SB2019) returns for its sixth edition, with 77 artists and art collectives from 36 countries and territories. Titled Every Step in the Right Direction, the international contemporary art exhibition invites the public to engage with the act of artistic exploration, drawing on the importance of making choices and taking steps to consider the conditions of contemporary life and the human endeavour for change. Commissioned by the National Arts Council and organised by SAM, the Singapore Biennale will run from 22 November 2019 until 22 March 2020 across 11 venues in the city. With a strong focus on Southeast Asia, the sixth edition welcomes over 150 works across a breadth of diverse mediums including film, installation, sound art and performance, as well as new commissions and works that have never been presented in contemporary art biennales and exhibitions internationally. SB2019’s opening weekend will feature programmes for the public, including artist performances, curator and artist tours and talks. Organised by Singapore Art Museum | Commissioned by National Arts Council, Singapore Supported by the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth 61 Stamford Road, #02-02, Stamford Court, Singapore 178892 . www.singaporeartmuseum.sg 1 Singapore Biennale 2019: Every Step in the Right Direction refers to the ethical imperative for both artists and audiences to make choices and take steps to reflect on the conditions of contemporary life. -

Behind the Thriving Scene of the Chinese Art Market -- a Research

Behind the thriving scene of the Chinese art market -- A research into major market trends at Chinese art market, 2006- 2011 Lifan Gong Student Nr. 360193 13 July 2012 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. F.R.R.Vermeylen Second reader: Dr. Marilena Vecco Master Thesis Cultural economics & Cultural entrepreneurship Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam 1 Abstract Since 2006, the Chinese art market has amazed the world with an unprecedented growth rate. Due to its recent emergence and disparity from the Western art market, it remains an indispensable yet unfamiliar subject for the art world. This study penetrates through the thriving scene of the Chinese art market, fills part of the gap by presenting an in-depth analysis of its market structure, and depicts the route of development during 2006-2011, the booming period of the Chinese art market. As one of the most important and largest emerging art markets, what are the key trends in the Chinese art market from 2006 to 2011? This question serves as the main research question that guides throughout the research. To answer this question, research at three levels is unfolded, with regards to the functioning of the Chinese art market, the geographical shift from west to east, and the market performance of contemporary Chinese art. As the most vibrant art category, Contemporary Chinese art is chosen as the focal art sector in the empirical part since its transaction cover both the Western and Eastern art market and it really took off at secondary art market since 2005, in line with the booming period of the Chinese art market. -

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People's Commune

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People’s Commune: Amateurism and Social Reproduction in the Maoist Countryside by Angie Baecker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Asian Languages and Cultures) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Xiaobing Tang, Co-Chair, Chinese University of Hong Kong Associate Professor Emily Wilcox, Co-Chair Professor Geoff Eley Professor Rebecca Karl, New York University Associate Professor Youngju Ryu Angie Baecker [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0182-0257 © Angie Baecker 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my grandmother, Chang-chang Feng 馮張章 (1921– 2016). In her life, she chose for herself the penname Zhang Yuhuan 張宇寰. She remains my guiding star. ii Acknowledgements Nobody writes a dissertation alone, and many people’s labor has facilitated my own. My scholarship has been borne by a great many networks of support, both formal and informal, and indeed it would go against the principles of my work to believe that I have been able to come this far all on my own. Many of the people and systems that have enabled me to complete my dissertation remain invisible to me, and I will only ever be able to make a partial account of all of the support I have received, which is as follows: Thanks go first to the members of my committee. To Xiaobing Tang, I am grateful above all for believing in me. Texts that we have read together in numerous courses and conversations remain cornerstones of my thinking. He has always greeted my most ambitious arguments with enthusiasm, and has pushed me to reach for higher levels of achievement. -

Reflections on Anonymity and Contemporaneity in Chinese Art Beatrice Leanza

PLACE UNDER THE LINE PLACE UNDER THE LINE : july / august 1 vol.9 no. 4 J U L Y / A U G U S T 2 0 1 0 VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4 INSIDE New Art in Guangzhou Reviews from London, Beijing, and San Artist Features: Gu Francisco Wenda, Lin Fengmian, Zhang Huan The Contemporary Art Academy of China Identity Politics and Cultural Capital in Contemporary Chinese Art US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4, JULY/AUGUST 2010 CONTENTS 2 Editor’s Note 33 4 Contributors 6 The Guangzhou Art Scene: Today and Tomorrow Biljana Ciric 15 On Observation Society Anthony Yung Tsz Kin 20 A Conversation with Hu Xiangqian 46 Biljana Ciric, Li Mu, and Tang Dixin 33 An interview with Gu Wenda Claire Huot 43 China Park Gu Wenda 46 Cubism Revisited: The Late Work of Lin Fengmian Tianyue Jiang 63 63 The Cult of Origin: Identity Politics and Cultural Capital in Contemporary Chinese Art J. P. Park 73 Zhang Huan: Paradise Regained Benjamin Genocchio 84 Contemporary Art Academy of China: An Introduction Christina Yu 87 87 Of Jungle—In Praise of Distance: Reflections on Anonymity and Contemporaneity in Chinese Art Beatrice Leanza 97 Shanghai: Art of the City Micki McCoy 104 Zhang Enli Natasha Degan 97 111 Chinese Name Index Cover: Zhang Huan, Hehe Xiexie (detail), 2010, mirror-finished stainless steel, 600 x 420 x 390 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Vol.9 No.4 1 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art president Katy Hsiu-chih Chien legal counsel Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C.C. -

Independent Cinema in the Chinese Film Industry

Independent cinema in the Chinese film industry Tingting Song A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2010 Abstract Chinese independent cinema has developed for more than twenty years. Two sorts of independent cinema exist in China. One is underground cinema, which is produced without official approvals and cannot be circulated in China, and the other are the films which are legally produced by small private film companies and circulated in the domestic film market. This sort of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has played a significant role in the development of Chinese cinema in terms of culture, economics and ideology. In contrast to the amount of comment on underground filmmaking in China, the significance of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has been underestimated by most scholars. This thesis is a study of how political management has determined the development of Chinese independent cinema and how Chinese independent cinema has developed during its various historical trajectories. This study takes media economics as the research approach, and its major methods utilise archive analysis and interviews. The thesis begins with a general review of the definition and business of American independent cinema. Then, after a literature review of Chinese independent cinema, it identifies significant gaps in previous studies and reviews issues of traditional definition and suggests a new definition. i After several case studies on the changes in the most famous Chinese directors’ careers, the thesis shows that state studios and private film companies are two essential domestic backers for filmmaking in China. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02450-2 — Art and Artists in China Since 1949 Ying Yi , in Collaboration with Xiaobing Tang Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02450-2 — Art and Artists in China since 1949 Ying Yi , In collaboration with Xiaobing Tang Index More Information Index Note: The artworks illustrated in this book are oil paintings unless otherwise stated. Figures 1–33 will be found in Plate section 1 (between pp. 49 and 72); Figures 34–62 in section 2 (between pp. 113 and 136); Figures 63–103 in section 3 (between pp. 199 and 238); Figures 104–161 in section 4 (between pp. 295 and 350). abstract art (Chinese) 163, 269–274, art market see commercialization of art 279 art publications (new) 86, 165–172 early 1980s 269–271 Artillery of the October Revolution 42 ’85 Movement –“China/Avant-Garde” Arts and Craft Movement 268 269–271 Attacking the Headquarters (Fig. 27) 1989 – present (post-modern) stage 273 avant-garde art (Chinese) 141, 146, 169, conceptual abstraction 273–274, 277–278 176, 181, 239, 245, 258, 264–265 expressive abstraction 273–274, 276 see also “China/Avant-Garde” material abstraction 277 exhibition schematic abstraction 245, 274 avant-garde art (Russian) 3–4 abstract art (Western) 147–148, 195–196, avant-garde art (Western) 100, 101, 267–268 see also Abstract 255–256, 257, 264 see also Modernism Expressionism; Hard-Edge / Structural Abstraction Bacon, Francis 243 Abstract Expressionism 256, 269, 274 Bao Jianfei 172 academic realism 245, 270 New Space No.1 167 academies see art academies Barbizon School 87 Ai Xinzhong 14 Bauhaus School 269 Ai Zhongxin 5 Beckmann, Max 246 amateur art/artists 35, 74–75, 106–108, Bei Dao 140 137–138, 141, -

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title "Music for a National Defense": Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7209v5n2 Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(13) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Howard, Joshua H. Publication Date 2014-12-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Music for a National Defense”: Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Joshua H. Howard, University of Mississippi Abstract This article examines the popularization of “mass songs” among Chinese Communist troops during the Anti-Japanese War by highlighting the urban origins of the National Salvation Song Movement and the key role it played in bringing songs to the war front. The diffusion of a new genre of march songs pioneered by Nie Er was facilitated by compositional devices that reinforced the ideological message of the lyrics, and by the National Salvation Song Movement. By the mid-1930s, this grassroots movement, led by Liu Liangmo, converged with the tail end of the proletarian arts movement that sought to popularize mass art and create a “music for national defense.” Once the war broke out, both Nationalists and Communists provided organizational support for the song movement by sponsoring war zone service corps and mobile theatrical troupes that served as conduits for musicians to propagate their art in the hinterland. By the late 1930s, as the United Front unraveled, a majority of musicians involved in the National Salvation Song Movement moved to the Communist base areas. Their work for the New Fourth Route and Eighth Route Armies, along with Communist propaganda organizations, enabled their songs to spread throughout the ranks.