Early Game Mind-Set

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework Ages Birth to Five

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework Ages Birth to Five 2015 R U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Office of Head Start Office of Head Start | 8th Floor Portals Building, 1250 Maryland Ave, SW, Washington DC 20024 | eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov Dear Colleagues: The Office of Head Start is proud to provide you with the newly revisedHead Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages Birth to Five. Designed to represent the continuum of learning for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers, this Framework replaces the Head Start Child Development and Early Learning Framework for 3–5 Year Olds, issued in 2010. This new Framework is grounded in a comprehensive body of research regarding what young children should know and be able to do during these formative years. Our intent is to assist programs in their efforts to create and impart stimulating and foundational learning experiences for all young children and prepare them to be school ready. New research has increased our understanding of early development and school readiness. We are grateful to many of the nation’s leading early childhood researchers, content experts, and practitioners for their contributions in developing the Framework. In addition, the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Head Start Research and Evaluation and the National Centers of the Office of Head Start, especially the National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning (NCQTL) and the Early Head Start National Resource Center (EHSNRC), offered valuable input. The revised Framework represents the best thinking in the field of early childhood. The first five years of life is a time of wondrous and rapid development and learning.The Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages Birth to Five outlines and describes the skills, behaviors, and concepts that programs must foster in all children, including children who are dual language learners (DLLs) and children with disabilities. -

Curriculum Planning and Development Division Post Sea Programme (April 2019 – July 2019) Physical Education

CURRICULUM PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT DIVISION POST SEA PROGRAMME (APRIL 2019 – JULY 2019) PHYSICAL EDUCATION ! ; : 9 6 : 9 8 7 ! 6 6 ! 1 4 5 , 0 ! 5 4 % , 4 3 2$ ! % $ ! 1 ' # ( /0 ! , . ' , - , + ! * ) ! ' ( ' # & ! % $ # " ! TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE Preamble 3 - 5 SECTION ONE (1) - Warm Up Games 6 - 9 SECTION TWO (2) - Intergenerational Games 10 - 14 Human Musical Chairs/Variation (Hoops) Skipping Los’ my glove on Satr’day Night Moral The Farmer in the Dell Brown Girl/Brown Boy in a ring Hopscotch Rounders Hand Game/Hand Clap SECTION THREE (3) - Teaching Games for Understanding/Game Sense Approach 15 - 30 Netball Basketball Modified Cricket Games/Cricket References ! ! ! PREAMBLE: Physical Education is one of the core subjects on the Trinidad and Tobago National Primary School Curriculum. According to Wuest & Bucher, 2015, “Physical Education is an educational process that has as its aim the improvement of human performance and enhancement of human development through the medium of physical activities”. One of the main goals of this subject is fulfilled through the ability to use knowledge of movement and skills to perform a wide range of physical activities (Wuest & Bucher, 2015). The Physical Education and Sport Unit of the Curriculum Planning and Development Division proposes to use Intergenerational Games and the Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU)/ Games Sense Approach as major aspects of the Post SEA Programme 2018/2019. The TGfU/Games Sense Approach has proven to be very relevant to students at the Post SEA level. Recent studies suggest that, as students progress through the teaching/learning stages, their engagement in the Approach, allows for a smoother transition from one level to another. -

Division of Child Care and Early Childhood Education Booklet Developed by Project Coordinator: Dot Brown President, Early Childhood Services, Inc

Division of Child Care and Early Childhood Education Booklet Developed By Project Coordinator: Dot Brown President, Early Childhood Services, Inc. Project Consultant: Beverly C. Wright Education Consultant Acknowledgments List of Reviewers Donna Alliston Denise Maxam Division of Child Care & Division of Child Care & Early Early Childhood Education Childhood Education Barbara Gilkey Sandra Reifeiss Arkansas State HIPPY Arkansas Department of Education/Special Education Janie Huddleston Division of Child Care & Kathy Stegall Early Childhood Education Division of Child Care & Early Childhood Education Traci Johnston Arkansas Cooperative Judith Thompson Extension Service Pulaski County Special School District Patty Malone Northwest Arkansas Family Janet Williams Child Care Association Arkansas Baptist State Convention Vicki Mathews Division of Child Care & Debbie Jo Wright Early Childhood Education Northwest Arkansas Family Child Care Association Credits Paige Beebe Gorman Photography Kaplan Early Learning Company Nancy P. Alexander Redwood Preschool Center pages 5, 6, 18 North Little Rock School District photoLitsey Design and Layout pages 9, 13, 15, 19 Massey Design Funding This project is funded by Arkansas Department of Human Services, Division of Child Care & Early Childhood Educa- tion through the Federal Child Care Development Fund. Division of Child Care & Early Childhood Education P.O. Box 1437, Slot S160, Little Rock, AR 72203-1437 Phone: 501-682-9699 • Fax: 501-682-4897 www.state.ar.us/childcare Date 2002 Welcome In this booklet, meet several preschool children through This booklet is words and pictures. Get a glimpse of their families and written for… their home life. View the children in their child care cen- ter, family child care home or preschool classroom. -

Base Running Drills

Base Running Drills 1. Batting Practice Base Running This is the best base running simulated drill work other than actual game base running experience. While your hitters are working on their hitting during batting practice your base runners should be working just as hard on their base running. This is why we call batting practice: YOUR MASCOT Practice. Every facet of the game, other than pitching, should be worked on during this practice session and therefore not just called BP or batting Practice. You should have five players in each group with one player hitting, one player of deck dry swinging and three others with one player at each base. Players at each base should be working on getting primary leads and reads off the bat as the hitter is making contact. The base runners can start on the outfield lip to not interfere with the extra infield ground balls and to not divot up the baselines. The runner on 3rd base should start deep and off the line, to limit the chance of getting hit by a line drive. They react at full speed, but only advance 4-5 steps and then go back to the base. They move up to the next base when the hitter is on his last swing of the round at which time the pitcher yells out “LIVE.” The defense, with one live player at each position, reacts along with the base runners to where the ball is hit. This drill will help condition your base runners to react to balls hit off the bat and limit double play line drives. -

MILO In2cricket Skills Program 5 - 6

MILO in2CRICKET introduces girls and boys, in grades 5-6, to Australia’s favourite sport. It’s great fun, kids learn the basic cricket skills and is available for kids of all abilities. MILO in2CRICKET Skills Program 5 - 6 The Australian Way Contents RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT 3 PROGRAM OUTLINE 3 ACTIVITY ESSENTIALS 4 HEALTH & P.E. CURRICULUM OUTCOMES 4 PROGRAM MAP 5 TIPS FOR THE DELIVERER 6 SKILL FOCUS 6 WEEK 1 LOCOMOTION RELAYS 7 GATE BOWLING 8 RAPID FIRE BOWLING 9 KNOCK EM DOWN – BUILD EM UP 10 WEEK 2 4 CORNERS 11 TARGET BATTING 12 SCORING SHOOT OUT 12 BATTING KNOCK-OUT 13 WEEK 3 DERBY CONES (6ERS VS THUNDER) 14 CATCHING 6ERS 15 TAKE WICKETS EVOLUTION 16 SKITTLE THE STUMPS 17 WEEK 4 CAPTAIN’S LOCOMOTION CALL 18 RAPID FIRE BATTING 19 ADDITIONAL ACTIVITIES 20 CONTENTS 2 Recommended Equipment for 24 Students EQUIPMENT QUANTITY LARGE BALLS (SCORCHER BALLS) 2 RUBBER CRICKET BALLS 24 ROPES (20M) 2 CONES 24 STUMPS 8 HIGH BOUNCE BALLS 6 BATS 24 MILO IN2CRICKET BAG 1 Program Outline LESSON 1 2 Focus Take Wickets Score Runs Prepare to Perform • Locomotion Relays • 4 Corners Activities • Gate Bowling • Target Batting • Rapid Fire Bowling • Scoring Shoot Out • Knock em down – Build em up • Batting Knock-out Stumps (End of play) Whole Group Discussion Whole Group Discussion LESSON 3 4 Focus Take Wickets Take Wickets & Score Runs Prepare to Perform • Derby Cones • Captain’s Locomotion Call Activities • Catching 6ers • Rapid Fire Batting • Take Wickets Evoluion • Skittle the Stumps Stumps (End of play) Whole Group Discussion Whole Group Discussion RECOMMENDED -

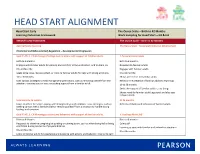

Head Start Alignment

HEAD START ALIGNMENT Head Start Early The Ounce Scale – Birth to 42 Months Learning Outcomes Framework Work Sampling for Head Start – H3 & H4 INFANTS AND TODDLERS The Ounce Scale – Birth to 42 Months Approaches to Learning The Ounce Scale – Social and Emotional Development Emotional and Behavioral Self-Regulation – Developmental Progression Goal IT-ATL 1. Child manages feelings and emotions with support of familiar adults. I. Personal Connections Birth to 9 Months: Birth to 8 months: Engages with familiar adults for calming and comfort, to focus attention, and to share joy. Responds to familiar adults 8 to 18 Months: Engages with familiar adults Seeks to be close, makes contact, or looks to familiar adults for help with strong emotions. 9 to 18 months: 16 to 36 Months: Shows preference for familiar adults Uses various strategies to help manage strong emotions, such as removing oneself from the Relies on the presence of familiar adults to try things situation, covering eyes or ears, or seeking support from a familiar adult. 19 to 36 months: Seeks the support of familiar adults to try things Shows need for familiar adult's approval and also acts independently Indicators by 36 months At 36 months Looks to others for help in coping with strong feelings and emotions. Uses strategies, such as Reflects attitudes and behaviors of familiar adults seeking contact with a familiar adult or removing oneself from a situation to handle strong feelings and emotions. Goal IT-ATL 2. Child manages actions and behaviors with support of familiar adults. II. Feelings About Self Birth to 9 Months: Birth to 8 months: Responds to attentive caregiving by quieting or calming down, such as when being fed or being Calms self comforted during moments of physical distress. -

Learn to Play Baseball the Way!

Saints Baseball WINTER Camps Youth Instructional Camp (Sat, 1/20) High School Prospect Skills Camp (Sat, 2/3) □ Youth Instructional Camp _____ x $50.00 ______ HS Prospect Skills Camp □ Two -Way Players ____ x $120.00 _____ □ Pitcher Only Players ____ x $ 80.00 _____ □ Position Players ____ x $ 80.00 _____ □ $10 discount for each sibling at camp _______ □ $10 group discount/player (6+ in group) _______ Saints Baseball Camp Total _______ LOUDONVILLE, NY 1221 NY LOUDONVILLE, ROAD 515 LOUDON YAMANE DAVID ATTN: CAMP BASEBALL SAINTS Camper(s) Name(s) Emergency Phone and Contact Person Saints Winter Email Address Baseball Camps st th Youth Camp, Grades 1 -8 th th Camper(s) Age(s) Camper(s) Grade(s) HS Prospect Camp, Grades 9 -12 High School (if applicable) S 1 Learn to play Medical Insurance Company Policy Number baseball the I hereby authorize a representative of Siena College baseball to take my child to a physician or hospital should the need arise. This also assures Siena College, that my child is in good physical condition, and in good health, and my child can participate in all of the showcase activities. I also release the Siena Athletic Department, the Baseball Coaching Staff, and participating coaches/employees from all rights and claims for damages, loss of property or person, or injuries that may be sustained during any involvement with the Camp Activities. way! Signature For additional Information, please contact: David Yamane, Assistant Baseball Coach Checks written to: Phone: 949.922.0800c, 518.782.6875b Saints Baseball Enterprises Email: [email protected] 515 Loudon Road Loudonville, NY 12211 Youth Instructional Camp Description Directions to Siena Campus Prospect Skills Camp The Saints Baseball Camps are a great way to The Saints Prospect Skills Camp gives players the get a head start on your baseball training. -

Changes to the Laws of Cricket

CHANGES TO THE LAWS OF CRICKET (With effect from 1st April 2019) OFFICIAL Marylebone Cricket Club Changes to The Laws of Cricket (With effect from 1st April 2019) 1 Changes to the Laws of In 2017, MCC published a new Code of Laws, which incorporated the most wide- Cricket – with effect from ranging and ambitious alterations to the Laws of Cricket for almost two decades. 1 April 2019 The Code has been well-received, and had a positive impact on cricket the world over. However, over the last two years, some issues have emerged, and so MCC has produced a second edition, which will come into force on 1st April 2019. The majority of these changes are simply minor corrections or clarifications, and will not make a material difference to the vast majority of cricket played around the world. One change removes a whole clause (the previous Law 41.19), but this is simply because, after changes to Law 41.2, the clause was duplication. However, there are a few significant changes. First, the decision was taken to rework Law 41.7, which relates to full-pitch deliveries over waist height (known colloquially as ‘beamers’). MCC listened to significant feedback and has handed more control to umpires to determine whether a delivery is dangerous. Also relevant to that Law, and at the behest of umpires, MCC has for the first time put into the Laws a definition of the waist – something that has long-since been a point of contention, particularly in the recreational game. There is also a slight change to Law 41.16, which should further confirm the principle, established in the 2017 Code, that it is the non-striker’s duty to remain in his/her ground until the bowler has released the ball. -

Arizona Early Learning Standards Standards Learning Early Arizona

Arizona Early Learning Standards 4th Edition ARIZONA EARLY LEARNING STANDARDS 4th Edition May 2018 Arizona Early Learning Standards 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 12 Social-Emotional Development Standard ......................................................................................................... 22 Strand 1: Self-Awareness and Emotional Skills ..................................................................................................... 25 Strand 2: Relationships and Social Skills ............................................................................................................... 28 Social-Emotional Integration and Alignment ......................................................................................................... 31 Approaches to Learning Standard .................................................................................................................... 42 Strand 1: Initiative and Curiosity ............................................................................................................................. 45 Strand 2: Attentiveness and Persistence ............................................................................................................... 47 Strand -

Translating Research Into Practice: Implications for Serving Families with Young Children

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 374 902 PS 022 726 TITLE Translating Research into Practice: Implications for Serving Families with Young Children. National Head Start Research Conference (2nd, Washington, D.C., November 4-7, 1993). Summary of Conference Proceedings. INSTITUTION Administration for Children, Youth, and Families (DHHS), Washington, D.C.; National Council of Jewish Women, New York, NY. Center for the Child.; Society for Research in Child Development. PUB DATE Nov 93 NOTE 481p. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Development; Child Health; *Child Welfare; *Demonstration Programs; Early Intervention; Family Health; *Family Programs; Literacy Education; Preschool Education; Program Improvement; Public Policy; Research Methodology; *Theory Practice Relationship; *Young Children IDENTIFIERS Administration for Children Youth and Families; Family Support; Program Characteristics; *Project Head Start ABSTRACT The papers in these proceedings focus primarily on features of the Head Start Progzam, contributions made to its research and its future direction. The first part of the proceedings contains presentations from the nine symposia, dealing with the following topics:(1) Head Start demonstration projects;(2) issues relating to education and the schools, such as learning and literacy; (3) child development and assessment;(4) child and family health; (5) integrated approaches to early intervention;,6) conceptual models for the study of multiethnic and minority families; (7) researcher and practitioner partnerships;(8) directions the Head Start program can take in terms of research, practice, and policy; and (9) miscellaneous issues such as involving fathers in the Head Start program, research issues in racial identity, and research methodologies. -

Fastpitch Softball Drill Book

Table of Contents Section Title Page 1 Defensive Drills Throwing & Catching 4-7 Fielding Ground Balls 7-15 Catching Fly Balls 16-21 Outfield Positions 21-29 Catcher 29-34 Infield 34-37 Pitcher 37-38 2 Pitching Mental Aspects 39-40 Mechanics 41-42 Drills 43-44 Common Errors 45-46 Mechanics Checklist 47 The Peel Drop 48 The Turn Over Drop 49 The Rise 50 The Curve 51 The Off Speed 52 The Pitch Out 53 Calling Pitches 54 Pre Game Warm Up 55 Fielding Responsibilities 56 Use of Charts & Stats 57 Video Taping & the Use of the Mound 58 Special Article – Searching Within for the Real Pitcher 59-60 2 Dealing with the Umpire 61 3 Hitting/Bunting/Slapping Hitting Basics 62 Hitting Mechanics 63 Hitting Fundamentals 64-65 Hitting Drills 66-68 Bunting 69-70 Left Handed Running Slap 71-72 4 Base Running Skills 73-75 Drills 76 5 Team Strategies Bunt Defenses 77-78 Outfield Game Plan 79-81 Outfield Play 82-83 Key Points for all Outfielders 84 6 Conditioning Drills 85-88 7 Coaching Practice Plans 89-90 Basic Coaching Information 91-92 Coaching Tips 93-94 “Ideal” Batting Order 95-96 Offensive Skills Checklist 97 Defensive Skills Checklist 98 Coaches Score Cards 99-101 Game Summary 102 3 Throwing & Catching 1. Tracking the Ball a. In partners, 1 ball per group b. Face each other, 2’ apart c. Hold ball above the head of your partner (fingers of glove up) d. Move the ball to waist level (glove up) e. Move ball to ground level (glove down) f.