Estonian Literary Magazine Autumn 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summaries Unknown Body of Thought and Practice in Esto- Nia, a Further Aim of the Article Was to Introduce This Stream of Feminist Thought to Estonian Read- Ers

As vegan feminism is a novel and virtually Summaries unknown body of thought and practice in Esto- nia, a further aim of the article was to introduce this stream of feminist thought to Estonian read- ers. Te paper hence discusses the relationship of vegan feminism with other, more established streams of feminist thought in Estonia and considers its potential contribution to feminist research and activism in Estonia. Challenging sexism while sup- Te article is based on a paper published in English in the Journal for Critical Animal Stud- porting speciesism: opin- ies (Aavik & Kase 2015). ions of Estonian feminists on animal rights and its links to feminism through a Infuence of place of employ- vegan feminist perspective ment on Estonian men’s plans of having children Kadri Aavik In this article, Kadri Aavik takes as a starting Mare Ainsaar, Ave Roots, point her own everyday experiences as a vegan Marek Sammul, Kati Orru feminist in Estonia and dilemmas stemming Te majority of studies of birthrate focus on from this identity. Relying on critical animal the attitudes and behavior of women. However, studies and vegan-feminist perspectives, she today couples ofen make decisions about having explores connections between feminism and children together and thus it is also necessary to animal liberation and veganism as bodies of study men’s plans about having children. A study thought and everyday critical practices challeng- of Estonian men conducted in 2015 showed that ing powerful systems of domination. Te paper Estonian men up to the age of 54 believe that an examines how 16 key Estonian feminists under- ideal number of children a family should have is stand human-animal relations, whether and over two and they wish to have the same number what connections they see between feminism of children. -

Poetry by Juhan Liiv

spring Elmestonian literary magazine 2013 Elm More information sources: Eesti Kirjanike Liit Estonian Writers’ Union Estnischer Schriftstellerverband 4 From enfant terrible to heavy artillery man by Peeter Helme Harju 1, 10146 Tallinn, Estonia Phone and fax: +372 6 276 410, +372 6 276 411 e-mail [email protected] www.ekl.ee Tartu branch: Vanemuise 19, 51014 Tartu Phone and fax: 07 341 073 [email protected] Estonian Literature Centre Eesti Kirjanduse Teabekeskus Sulevimägi 2-5 10123 Tallinn, Estonia 8 Jüri Talvet on Juhan Liiv www.estlit.ee/ and his poetry by Rein Veidemann The Estonian Institute would like to thank the Estonian Ministry of Culture for their support. www.estinst.ee contents no 36. Spring 2013 12 Poetry by Juhan Liiv 16 Maarja Pärtna – thresholds and possibilities by Jayde Will 18 Poetry by Maarja Pärtna 22 Russians in Estonia, and the town of Sillamäe. Andrei Hvostov’s passion and misery by Sirje Olesk 26 HeadRead 27 A new book by Kristiina Ehin 28 Short outlines of books by Estonian authors by Rutt Hinrikus, Brita Melts and Janika Kronberg 42 Estonian literature in translation 2012 Compiled by the Estonian Literature Centre © 2013 by the Estonian Institute; Suur-Karja 14 10140 Tallinn Estonia; ISSN 1406-0345 email:[email protected] www.estinst.ee phone: (372) 631 43 55 fax: (372) 631 43 56 Editorial Board: Peeter Helme, Mati Sirkel, Jaanus Vaiksoo, Piret Viires Editor: Tiina Randviir Translators: H. L. Hix, Marika Liivamagi, Tiina Randviir, Juri Talvet, Jayde Will © Language editor: Richard Adang Layout: Marius Peterson Cover photo: (:)kivisildnik (Scanpix) Estonian Literary Magazine is included in the EBSCO Literary Reference Center (:)kivisildnik by Peeter Helme One of the first times (:)kivisildnik (49) was mentioned in the Estonian Literary Magazine was in 1999, when an article about someone else dryly noted that (:)kivisildnik was an author who used “obscene language”. -

Estonian Literary Magazine Autumn 2020

The Bard Like the roar of waves on the foamy river, plunging from the rocks down into the dale; like the thunder of the heavens rolling awesome under black clouds: so runs song fair stream of fire. Like a wellspring of light Estonian Literary Magazine stands the honoured bard amongst his brothers. Autumn 2020 The thunder rolls and the woods fall silent: the bard raises his voice · 51 pours forth the sap of song from his lips, 2020 while all around MN U silent as the sea cliffs T U A the people stand and listen. · KRISTJAN JAAK PETERSON, 1819 TRANSLATED BY ERIC DICKENS ESTONIAN LITERARY MAGAZINE LITERARY ESTONIAN ESTONIAN LITERARY MAGAZINE · autumn 2020 · 51 Nº51 elm.estinst.ee MORE INFORMATION: ESTONIAN INSTITUTE Eesti Instituut Suur-Karja 14, 10140 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 631 4355 www.estinst.ee ESTONIAN LITERATURE CENTRE Eesti Kirjanduse Teabekeskus Sulevimägi 2-5 10123 Tallinn, Estonia www.estlit.ee ESTONIAN WRITERS’ UNION Eesti Kirjanike Liit Harju 1, 10146 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 6 276 410, +372 6 276 411 [email protected] www.ekl.ee The current issue of ELM was supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia and Estonian Ministry of Culture © 2020 by the Estonian Institute. ISSN 1406-0345 Editor: Berit Kaschan · Translators: Adam Cullen · Language editor: Robyn Laider Layout: Piia Ruber Editorial Board: Tiit Aleksejev, Adam Cullen, Peeter Helme, Helena Koch, Ilvi Liive, Helena Läks, Piret Viires On the Cover: Mudlum Photo: Piia Ruber Estonian Literary Magazine is included in the EBSCO Literary Reference Center. THE FRONT COVER OF THE THIRD ISSUE OF ESTONIAN LITERARY MAGAZINE, PUBLISHED IN 1996. -

Ja „25 Kauneimat Raamatut“ 1956 – 2010“ Mille Juhendajad on Kurmo Konsa (Phd) Ja Tiit Hennoste (Phd)

TARTU ÜLIKOOL Humanitaarteaduste ja kunstide valdkond Ajaloo ja arheoloogia instituut Infokorralduse õppekava Eesti raamatukonkursid „25 parimat raamatut“ ja „25 kauneimat raamatut“ 1956 – 2010 Magistritöö infokorralduse erialal Edith Hermann Juhendajad Tiit Hennoste, PhD Kurmo Konsa, PhD Tartu 2016 SISUKORD SISSEJUHATUS ......................................................................................................................................4 Lühendid ...............................................................................................................................................6 1. TEOREETILISED LÄHTEKOHAD ..................................................................................................7 1.1. Raamat kui artefakt .......................................................................................................................7 1.2. Ilu ja kogemuse kontekst .............................................................................................................10 1.3. Eesmärk ja uurimisküsimused .....................................................................................................12 2. UURIMISTÖÖ EMPIIRILINE KÄSITLUS JA TEEMA VARASEMAD KÄSITLUSED. AJALOOLINE JA RAHVUSVAHELINE KONTEKST NING EESTI KONKURSSIDE EELLUGU13 2.1. Empiirilise uurimustöö käik ........................................................................................................13 2.2. Teema varasemad käsitlused .......................................................................................................17 -

Eesti Rahvusbibliograafia Raamatud

EESTI RAHVUSBIBLIOGRAAFIA RAAMATUD ESTONIAN NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS 2006 1 Jaanuar - January jaanuar.p65 1 06.03.06, 13:05 Koostaja Compiled by Eesti Rahvusraamatukogu National Library of Estonia Kogude arenduse osakond Department of Collection Development and Documentation Kättesaadav ka / Available also http://erb.nlib.ee Ilmub 12 numbrit aastas / Issued monthly Autoriõigus Eesti Rahvusraamatukogu, 2006 Eesti Rahvusbibliograafia Series of seeriad: the Estonian National Bibliography: RAAMATUD BOOKS PERIOODIKA SERIALS MUUSIKA MUSIC KAARDID MAPS Väljaandeid müüb: The publications can be purchased from Eesti Rahvusraamatukogus asuv the bookshop Lugemisvara in the raamatukauplus Lugemisvara National Library of Estonia Hind 70 krooni Price 70 krooni Tõnismägi 2 15189 Tallinn jaanuar.p65 2 06.03.06, 13:05 SAATEKS Raamatud on Eesti rahvusbibliograafia osa, mis ilmub 1999. aastast alates kuuvihikuna ja aastaväljaandena. Aastatel 1946-1991 kandis väljaanne pealkirja Raamatukroonika. Raamatud kajastab Eestis kõigis keeltes ja väljaspool Eestit ilmunud eestikeelseid raamatuid, nii trüki- kui ka elektroonilisi väljaandeid ning mittemuusikalisi auviseid. Raamatud sisaldab ka pimedaile ja vaegnägijaile mõeldud teavikuid. Nimestik ei hõlma piiratud lugemisotstarbe või lühiajalise tähtsusega trükiseid (näit. asutuste kvartaliaruandeid, reklaamväljaandeid jms.). Kuuvihik peegeldab ühe kuu jooksul Eesti Rahvusraamatukogusse saabunud uued teavikud, mida kirjeldatakse rahvusvaheliste kirjereeglite ISBD(M), ISBD(NBM) ja ISBD(ER) järgi. Lisaks kajastab -

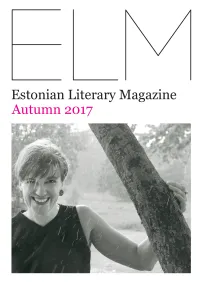

Estonian Literary Magazine · Autumn 2017 · Photo by Kalju Suur Kalju by Maimu Berg · Photo

Contents 2 A women’s self-esteem booster by Aita Kivi 6 Tallinn University’s new “Estonian Studies” master´s program by Piret Viires 8 The pain treshold. An interview with the author Maarja Kangro by Tiina Kirss 14 The Glass Child by Maarja Kangro 18 “Here I am now!” An interview with Vladislav Koržets by Jürgen Rooste 26 The signs of something going right. An interview with Adam Cullen 30 Siuru in the winds of freedom by Elle-Mari Talivee 34 Fear and loathing in little villages by Mari Klein 38 Being led by literature. An interview with Job Lisman 41 2016 Estonian Literary Awards by Piret Viires 44 Book reviews by Peeter Helme and Jürgen Rooste A women’s self-esteem booster by Aita Kivi The Estonian writer and politician Maimu Berg (71) mesmerizes readers with her audacity in directly addressing some topics that are even seen as taboo. As soon as Maimu entered the Estonian (Ma armastasin venelast, 1994), which literary scene at the age of 42 with her dual has been translated into five languages. novel Writers. Standing Lone on the Hill Complex human relationships and the (Kirjutajad. Seisab üksi mäe peal, 1987), topic of homeland are central in her mod- her writing felt exceptionally refreshing and ernist novel Away (Ära, 1999). She has somehow foreign. Reading the short stories also psychoanalytically portrayed women’s and literary fairy tales in her prose collection fears and desires in her prose collections I, Bygones (On läinud, 1991), it was clear – this Fashion Journalist (Mina, moeajakirjanik, author can capably flirt with open-minded- 1996) and Forgotten People (Unustatud ness! It was rare among Estonian authors at inimesed, 2007). -

Leelo Tungal Biography

Photo by Stina Kase Contents Our Leelo. T e Candididate’s Contribution to Literature for Young People ................... 3 Leelo Tungal Biography ................... 9 Interview Leelo Tungal through the Horrors towards the Book ................... 12 Books by Leelo Tungal submitted to the Jury ................... 19 Comrade Kid and the Grown-Ups. One More Story of a Happy Childhood ................... 20 Midsummer. Poetry for Children from 1972-2012 ................... 40 Kristiina, the Middle One ................... 47 Children of Maimetsa ................... 49 Barbara and Dogs ................... 51 Bibliography, Translations, Prizes ................... 53 Our Leelo. The Candididate’s Contribution to Literature for Young People Our Leelo by Mare Müürsepp Estonian Literary Magazine, no 2, 2016 I’ll start with children’s assessment. We had a group of third-grade students draf a list of who they believed were important public f gures in Estonia. We used the list to make a presentation for our foreign pen-pals entitled “Famous Estonians”. Tied for f rst place in the children’s ranking were Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves, a teenage world-champion freestyle skier Kelly Sildaru, and Leelo Tungal. Clearly, Tungal is not an “ordinary” children’s author, but a symbolic f gure. Tungal’s writings deal with children and their families and span the media of common reading materials, schoolbooks (her ABC-primer characters Adam and Anna, who have endured for decades), song repertoires, journalism, and public performances. Although the author has written many librettos and drama pieces, she has def nitely enjoyed her greatest public fame at the Estonian Song Festivals, at which song authors are called to take the stage before hundreds of thousands of cheering and clapping audience members expressing delight with an intensity uncommon for Estonians. -

Estonian Literary Magazine Spring 2019

Estonian Literary Magazine Spring 2019 73 Nº48 elm.estinst.ee MORE INFORMATION: ESTONIAN INSTITUTE Eesti Instituut Suur-Karja 14, 10140 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 631 4355 www.estinst.ee ESTONIAN LITERATURE CENTRE Eesti Kirjanduse Teabekeskus Sulevimägi 2-5 10123 Tallinn, Estonia www.estlit.ee ESTonian Writers’ UNION Eesti Kirjanike Liit Harju 1, 10146 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 6 276 410, +372 6 276 411 [email protected] www.ekl.ee The current issue of ELM was supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia. © 2019 by the Estonian Institute. ISSN 1406-0345 Editorial Board: Tiit Aleksejev, Adam Cullen, Peeter Helme, Ilvi Liive, Helena Läks, Piret Viires Editor: Berit Kaschan · Translator: Adam Cullen · Language editor: Robyn Laider Layout: Piia Ruber On the Cover: Eda Ahi. Photo by Piia Ruber Estonian Literary Magazine is included in the EBSCO Literary Reference Center. Contents 2 Places of writing by Tiit Aleksejev 5 Hortus Conclusus by Tiit Aleksejev 8 Warmth and Peturbation. An interview with Eda Ahi by ELM 16 Poetry by Eda Ahi 20 A Brief Guide to Toomas Nipernaadi's Estonia by Jason Finch 24 The 2018 Turku Book Fair: Notes from the organiser by Sanna Immanen 28 Translator Danutė Giraitė: work = hobby = lifestyle. An interview by Pille-Riin Larm 34 Poète maudit? An interview with Kristjan Haljak by Siim Lill 40 Poetry by Kristjan Haljak 42 Lyrikline – Listen to the poet. 20 years of spoken poetry by Elle-Mari Talivee 44 Reeli Reinaus: From competition writer to true author by Jaanika Palm 48 Marius, Magic and Lisa the Werewolf by Reeli Reinaus 52 Ene Mihkelson: “How to become a person? How to be a person?” by Aija Sakova 56 Book reviews by Peeter Helme, Krista Kumberg, Elisa-Johanna Liiv, Siim Lill, Maarja Helena Meriste, and Tiina Undrits 70 Selected translations 2018 Places of writing by Tiit Aleksejev Places of writing can be divided into two: the ancient Antioch, which I had been those where writing is possible in general, attempting, unsuccessfully, to recreate for and those that have a direct connection to quite a long time already. -

Estonian Literary Magazine Autumn 2018 Nº47 Elm.Estinst.Ee

Estonian Literary Magazine Autumn 2018 Nº47 elm.estinst.ee MORE INFORMATION SOURCES: ESTONIAN INSTITUTE Eesti Instituut Suur-Karja 14, 10140 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 631 4355 www.estinst.ee ESTONIAN LITERATURE CENTRE Eesti Kirjanduse Teabekeskus Sulevimägi 2-5 10123 Tallinn, Estonia www.estlit.ee ESTonian Writers’ UNION Eesti Kirjanike Liit Harju 1, 10146 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 6 276 410, +372 6 276 411 [email protected] www.ekl.ee The current issue of ELM was supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia © 2018 by the Estonian Institute. ISSN 1406-5703 Editorial Board: Tiit Aleksejev, Adam Cullen, Peeter Helme, Ilvi Liive, Helena Läks, Piret Viires Editor: Berit Kaschan · Translator: Adam Cullen · Language editor: Robyn Laider Layout: Piia Ruber On the Cover: Vahur Afanasjev. Photo by Piia Ruber Estonian Literary Magazine is included in the EBSCO Literary Reference Center Contents 2 A Perfect Day by Eva Koff 4 A small assortment of the Estonian new drama competition’s tastiest treats by Mihkel Seeder 8 Most important of all is the person. An interview with Vahur Afanasjev by Holger Kaints 18 Serafima and Bogdan by Vahur Afanasjev 22 The Dodo’s decision by Maarja Kangro 28 It’s worth seeing what’s good. An interview with Kadri Hinrikus by Kristi Helme 32 EstLitFest: an open-air snow globe on foreign soil by Adam Cullen 36 Being one with the world, i.e. why leave home? An interview with Viivi Luik by Aija Sakova 40 One nature, one mind, one cloud. The ecognosis of Aare Pilv by Hasso Krull 46 Book reviews by Maria Lee Liivak, Peeter Helme, Oliver Berg and Maarja Helena Meriste A Perfect Day by Eva Koff “A Perfect Day” is a new ELM column, in which individuals associated with liter- ature in Estonia share their recipes for a perfect day. -

MIND TÚL VAGYUNK a HATÁRON All of Us Here Are Over the Edge

Project5.qxp_Layout 1 2019. 09. 10. 11:05 Page 1 MIND TÚL VAGYUNK A HATÁRON All of us here are over the edge Baltic Poetry: Balti Költészeti Fesztivál Budapest, 2019. szeptember 18 –19. Project5.qxp_Layout 1 2019. 09. 10. 11:05 Page 2 Project5.qxp_Layout 1 2019. 09. 10. 11:05 Page 3 MIND TÚL VAGYUNK A HATÁRON All of us here are over the edge Irodalmi antológia BALTI KÖLTÉSZETI FESZTIVÁL BALTIC POETRY 2019. szeptember 18 –19. Szépírók Társasága Budapest, 2019 Project5.qxp_Layout 1 2019. 09. 10. 11:05 Page 4 A kiadvány megjelenését a Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum támogatta A verseket Krasztev Péter, Lengyel Tóth Krisztina, Márkus Virág, Timár Bogáta és Tölgyesi Beatrix fordította. A műfordításokat Deres Kornélia, Mesterházi Mónika, Szilágyi Ákos és Szkárosi Endre lektorálta. Copyright © Szépírók Társasága, szerzők, fordítók, 2019 ISBN 978-615-00-6215-0 Kiadja: Szépírók Társasága A kiadásért felel: Szkárosi Endre Szerkesztő: Szokács Kinga Technikai szerkesztő: Keresztes Mária Korrektor: Szatmári Réka Borító: Gábor Tamás Indiana Nyomtatás, kötészet: Raszter Nyomda, Budapest Project5.qxp_Layout 1 2019. 09. 10. 11:05 Page 5 TARTALOMJEGYZÉK Előszó 6 Foreword 7 Marius Burokas (LT) 9 Kristiina Ehin (EE) 19 Inga Gaile (LV) 30 Maarja Kangro (EE) 44 Giedré Kazlauskaité (LT) 53 Kalju Kruusa (EE) 66 Sergej Timofejev (LV) 73 Krišjānis Zeļģis (LV) 80 Borda Réka (H) 86 Cselényi Béla (H) 94 Deres Kornélia (H) 98 Ferencz Mónika (H) 102 Ladik Katalin (H) 108 Lipcsey Emőke (H) 112 Nagy Zopán (H) 117 Tóth Kinga (H) 122 Vajna Ádám (H) 128 Fordítók 136 Translators 137 Fesztiváldokumentumok 138 Project5.qxp_Layout 1 2019. 09. 10. -

Kroonika Algus Layout 1

KROONIKA SISUKORD I osa ÜLDSTATISTIKA 186 Statistikas osalevad etendusasutused 186 Etenduspaigad Eestis 188 Teatrite esinemised välismaal 189 Festivalid Eestis 195 Külalisteatrid ja -esinejad Eestis 204 Tiia Sippol. Ülevaade teatritegevusest Eestis 2016. aastal 208 Toomas Peterson. Pealinn vs regioonid 212 II osa TEATRITE ETENDUSTEGEVUS 215 Teatrite tegevusülevaated (järjekord tabelis lk 188), statsionaarid, uuslavastused, repertuaar, tugitegevus ja ülevaade tulude-kulude jaotumisest. 2016. aasta uuslavastusi 328 Raadioteater 337 Teatrikoolid 338 Harrastusteater Eestis 340 Teatriorganisatsioonid: 1. ASSITEJ Eesti Keskus 349 2. Eesti Etendusasutuste Liit 349 3. Eesti Harrastusteatrite Liit 350 4. Eesti Kaasaegse Tsirkuse Arenduskeskus 351 5. Eesti Tantsuhariduse ja -kunstnike Ühendus 351 6. Eesti Teatri Agentuur 352 7. Eesti Teatriliit 353 8. Eesti Teatriuurijate ja -kriitikute Ühendus 360 9. UNIMA Eesti Keskus 361 10. Eesti Teatri- ja Muusikamuuseum 361 III osa VARIA Auhinnad 363 Eesti teatri aastaauhinnad 365 Nimelised auhinnad ja stipendiumid 367 Kolleegipreemiad 370 Publikupreemiad 373 Tunnustused välismaalt 374 Konverentsid, seminarid jm 377 Näitused 384 Teatrierialade lõpetajad 385 Mängufilmid, lavastuste telesalvestised 387 Ilmunud raamatud ja videosalvestised 393 In memoriam 397 ÜLDSTATISTIKA Ülevaade statistikast Eesti Teatri Agentuur on koostöös kultuuri- ministeeriumi ja Eesti teatritega kogunud valdkonna statistikat alates 2004. aastast, käesolev aastaülevaade on kolmeteistküm- nes. Aastatel 2004–2011 kogutud statistika anti -

Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre Karol Kisiel Vision of the Artistic Profile of the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir

Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre Karol Kisiel Vision of the artistic profile of the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir represented by its chief conductors: Tõnu Kaljuste, Paul Hillier and Daniel Reuss A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Supervisor: Prof. Toomas Siitan Tallinn 2013 Vision of the artistic profile of the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir represented by its chief conductors: Tõnu Kaljuste, Paul Hillier and Daniel Reuss Abstract The research focuses on the impact of the chief conductors of the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir (henceforth EPCC) on the choir’s artistic profile. The author concentrates mainly on the comparison of the conductors’ approach towards the EPCC’s sound and its specifics. The researchers point of view on what are the essential elements contributing to the determining the quality of the choir’s sound serves as the methodological model. Based on this, the author compares the conductors approach towards mentioned elements, and pictures its general influence on the EPCC’s sound. Since the differences between the musical background and artistic principles represented by all conductors are notable (due to their different nationalities, education, technical skills etc.), it is valuable to observe the choir’s response to their individual ideas. An important part of the dissertation are the interviews done by the author with all of the chief conductors of the EPCC, interviews with singers expressing their thoughts on each conductor and his vision for the choir, and the comparison of the recordings of Kreek’s Psalms which have been done by the EPCC under all of the artistic directors.