Mere Image: Caravaggio, Virtuosity, and Medusa's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Framing the Painting: the Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Author[S]: Leonée Ormond Source: Moveabletype, Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5300/framing-the-painting-the-victorian-picture-sonnet-author-s-leon%C3%A9e-ormond-source-moveabletype-vol-5300.webp)

Framing the Painting: the Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Author[S]: Leonée Ormond Source: Moveabletype, Vol

Framing the Painting: The Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Author[s]: Leonée Ormond Source: MoveableType, Vol. 2, ‘The Mind’s Eye’ (2006) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.012 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2006 Leonée Ormond. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Framing the Painting: The Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Leonée Ormond During the Victorian period, the short poem which celebrates a single work of art became increasingly popular. Many, but not all, were sonnets, poems whose rectangular shape bears a satisfying similarity to that of a picture frame. The Italian or Petrarchan (rather than the Shakespearean) sonnet was the chosen form and many of the poems make dramatic use of the turn between the octet and sestet. I have chosen to restrict myself to sonnets or short poems which treat old master paintings, although there are numerous examples referring to contemporary art works. Some of these short “painter poems” are largely descriptive, evoking colour, design and structure through language. Others attempt to capture a more emotional or philosophical effect, concentrating on the response of the looker-on, usually the poet him or herself, or describing the emotion or inspiration of the painter or sculptor. Some of the most famous nineteenth century poems on the world of art, like Browning’s “Fra Lippo Lippi” or “Andrea del Sarto,” run to greater length. -

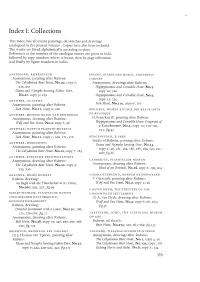

Index I: Collections

Index I: Collections This index lists ail extant paintings, oil sketches and drawings catalogued in the present volume . Copies have also been included. The works are listed alphabetically according to place. References to the number of the catalogue entries are given in bold, followed by copy numbers where relevant, then by page references and finally by figure numbers in italics. AMSTERDAM, RIJKSMUSEUM BRUGES, STEDEEÏJKE MUSEA, STEINMETZ- Anonymous, painting after Rubens : CABINET The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .20, copy 6; Anonymous, drawings after Rubens: 235, 237 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, Diana and Nymphs hanting Fallow Deer, copy 12; 120 N o.21, copy 5; 239 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, cop y 13; 120 ANTWERP, ACADEMY Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o.ne, copy 6; 177 Lion Hunt, N o.11, copy 2; 162 BRUSSELS, MUSÉES ROYAUX DES BEAUX-ARTS DE BELGIQUE ANTWERP, MUSEUM MAYER VAN DEN BERGH Anonymous, drawing after Rubens: H.Francken II, painting after Rubens: Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt: Fragment of W olf and Fox Hunt, N o .2, copy 7; 96 a Kunstkammer, N o.5, copy 10; 119-120, ANTW ERP, MUSEUM PLANTIN-M O RETUS 123 ;fig .4S Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o .n , copy 1; 162, 171, 178 BÜRGENSTOCK, F. FREY Studio of Rubens, painting after Rubens: ANTWERP, RUBENSHUIS Diana and Nymphs hunting Deer, N o .13, Anonymous, painting after Rubens : copy 2; 46, 181, 182, 186, 188, 189, 190, 191, The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .12, copy 7; 185 208; fig.S6 ANTWERP, STEDELIJK PRENTENKABINET Anonymous, -

Batman Takes Parade by Storm (Thesis by Jared Goodrich)

Jared Goodrich Batman Takes Parade By Storm (How Comic Book Culture Shaped a Small City’s Halloween parade) History Research Seminar Spring 2020 1 On Saturday, October 26th, 2019, the participants lined up to begin of the Rutland Halloween Parade. 10,000 people came to the small city of Rutland to view the famed Halloween parade for its 60th year. Over 72 floats had participated and 1700 people led by the Skelly Dancers. School floats with specific themes to the Star Wars non-profit organization the 501st Legion to droves and rows of different Batman themed floats marched throughout the city to celebrate this joyous occasion. There have been many narratives told about this historic Halloween parade. One specific example can be found on the Rutland Historical Society’s website, which is the documentary called Rutland Halloween Parade Hijinks and History by B. Burge. The standard narrative told is that on Halloween night in 1959, the Rutland area was host to its first Halloween parade, and it was a grand show in its first year. The story continues that a man by the name of Tom Fagan loved what he saw and went to his friend John Cioffredi, who was the superintendent of the Rutland Recreation Department, and offered to make the parade better the next year. When planning for the next year, Fagan suggested that Batman be a part of the parade. By Halloween of 1961, Batman was running the parade in Rutland, and this would be the start to exciting times for the Rutland Halloween parade.1 Five years into the parade, the parade was the most popular it had ever been, and by 1970 had been featured in Marvel comics Avengers Number 83, which would start a major event later in comic book history. -

Il Lasca’ (1505‐1584) and the Burlesque

Antonfrancesco Grazzini ‘Il Lasca’ (1505‐1584) and the Burlesque Poetry, Performance and Academic Practice in Sixteenth‐Century Florence Antonfrancesco Grazzini ‘Il Lasca’ (1505‐1584) en het burleske genre Poëzie, opvoeringen en de academische praktijk in zestiende‐eeuws Florence (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. J.C. Stoof, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 9 juni 2009 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door Inge Marjo Werner geboren op 24 oktober 1973 te Utrecht Promotoren: Prof.dr. H.A. Hendrix Prof.dr. H.Th. van Veen Contents List of Abbreviations..........................................................................................................3 Introduction.........................................................................................................................5 Part 1: Academic Practice and Poetry Chapter 1: Practice and Performance. Lasca’s Umidian Poetics (1540‐1541) ................................25 Interlude: Florence’s Informal Literary Circles of the 1540s...........................................................65 Chapter 2: Cantando al paragone. Alfonso de’ Pazzi and Academic Debate (1541‐1547) ..............79 Part 2: Social Poetry Chapter 3: La Guerra de’ Mostri. Reviving the Spirit of the Umidi (1547).......................................119 Chapter 4: Towards Academic Reintegration. Pastoral Friendships in the Villa -

Reading 1.2 Caravaggio: the Construction of an Artistic Personality

READING 1.2 CARAVAGGIO: THE CONSTRUCTION OF AN ARTISTIC PERSONALITY David Carrier Source: Carrier, D., 1991. Principles of Art History Writing, University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp.49–79. Copyright ª 1991 by The Pennsylvania State University. Reproduced by permission of the publisher. Compare two accounts of Caravaggio’s personality: Giovanni Bellori’s brief 1672 text and Howard Hibbard’s Caravaggio, published in 1983. Bellori says that Caravaggio, like the ancient sculptor Demetrius, cared more for naturalism than for beauty. Choosing models, not from antique sculpture, but from the passing crowds, he aspired ‘only to the glory of colour.’1 Caravaggio abandoned his early Venetian manner in favor of ‘bold shadows and a great deal of black’ because of ‘his turbulent and contentious nature.’ The artist expressed himself in his work: ‘Caravaggio’s way of working corresponded to his physiognomy and appearance. He had a dark complexion and dark eyes, black hair and eyebrows and this, of course, was reflected in his painting ‘The curse of his too naturalistic style was that ‘soon the value of the beautiful was discounted.’ Some of these claims are hard to take at face value. Surely when Caravaggio composed an altarpiece he did not just look until ‘it happened that he came upon someone in the town who pleased him,’ making ‘no effort to exercise his brain further.’ While we might think that swarthy people look brooding more easily than blonds, we are unlikely to link an artist’s complexion to his style. But if portions of Bellori’s text are alien to us, its structure is understandable. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism Author(S): Alina A

Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism Author(s): Alina A. Payne Source: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 1994), pp. 322-342 Published by: Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/990940 Accessed: 15/10/2009 16:45 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sah. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. http://www.jstor.org Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism ALINA A. -

Pictorial Real, Historical Intermedial. Digital Aesthetics and the Representation of History in Eric Rohmer's the Lady And

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 12 (2016) 27–44 DOI: 10.1515/ausfm-2016-0002 Pictorial Real, Historical Intermedial. Digital Aesthetics and the Representation of History in Eric Rohmer’s The Lady and the Duke Giacomo Tagliani University of Siena (Italy) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In The Lady and the Duke (2001), Eric Rohmer provides an unusual and “conservative” account of the French Revolution by recurring to classical and yet “revolutionary” means. The interpolation between painting and film produces a visual surface which pursues a paradoxical effect of immediacy and verisimilitude. At the same time though, it underscores the represented nature of the images in a complex dynamic of “reality effect” and critical meta-discourse. The aim of this paper is the analysis of the main discursive strategies deployed by the film to disclose an intermedial effectiveness in the light of its original digital aesthetics. Furthermore, it focuses on the problematic relationship between image and reality, deliberately addressed by Rohmer through the dichotomy simulation/illusion. Finally, drawing on the works of Louis Marin, it deals with the representation of history and the related ideology, in order to point out the film’s paradoxical nature, caught in an undecidability between past and present. Keywords: Eric Rohmer, simulation, illusion, history and discourse, intermediality, tableau vivant. The representation of the past is one of the domains, where the improvement of new technologies can effectively disclose its power in fulfilling our “thirst for reality.” No more cardboard architectures nor polystyrene stones: virtual environments and motion capture succeed nowadays in conveying a truly believable reconstruction of distant times and worlds. -

Experience the Flemish Masters Programme 2018 - 2020

EXPERIENCE THE FLEMISH MASTERS PROGRAMME 2018 - 2020 1 The contents of this brochure may be subject to change. For up-to-date information: check www.visitflanders.com/flemishmasters. 2 THE FLEMISH MASTERS 2018-2020 AT THE PINNACLE OF ARTISTIC INVENTION FROM THE MIDDLE AGES ONWARDS, FLANDERS WAS THE INSPIRATION BEHIND THE FAMOUS ART MOVEMENTS OF THE TIME: PRIMITIVE, RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE. FOR A PERIOD OF SOME 250 YEARS, IT WAS THE PLACE TO MEET AND EXPERIENCE SOME OF THE MOST ADMIRED ARTISTS IN WESTERN EUROPE. THREE PRACTITIONERS IN PARTICULAR, VAN EYCK, BRUEGEL AND RUBENS ROSE TO PROMINENCE DURING THIS TIME AND CEMENTED THEIR PLACE IN THE PANTHEON OF ALL-TIME GREATEST MASTERS. 3 FLANDERS WAS THEN A MELTING POT OF ART AND CREATIVITY, SCIENCE AND INVENTION, AND STILL TODAY IS A REGION THAT BUSTLES WITH VITALITY AND INNOVATION. The “Flemish Masters” project has THE FLEMISH MASTERS been established for the inquisitive PROJECT 2018-2020 traveller who enjoys learning about others as much as about him or The Flemish Masters project focuses Significant infrastructure herself. It is intended for those on the life and legacies of van Eyck, investments in tourism and culture who, like the Flemish Masters in Bruegel and Rubens active during are being made throughout their time, are looking to immerse th th th the 15 , 16 and 17 centuries, as well Flanders in order to deliver an themselves in new cultures and new as many other notable artists of the optimal visitor experience. In insights. time. addition, a programme of high- quality events and exhibitions From 2018 through to 2020, Many of the works by these original with international appeal will be VISITFLANDERS is hosting an Flemish Masters can be admired all organised throughout 2018, 2019 abundance of activities and events over the world but there is no doubt and 2020. -

BOZZETTO STYLE” the Renaissance Sculptor’S Handiwork*

“BOZZETTO STYLE” The Renaissance Sculptor’s Handiwork* Irving Lavin Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton NJ It takes most people much time and effort to become proficient at manipulating the tools of visual creation. But to execute in advance sketches, studies, plans for a work of art is not a necessary and inevitable part of the creative process. There is no evidence for such activity in the often astonishingly expert and sophisticated works of Paleolithic art, where images may be placed beside or on top of one another apparently at random, but certainly not as corrections, cancellations, or “improved” replacements. Although I am not aware of any general study of the subject, I venture to say that periods in which preliminary experimentation and planning were practiced were relatively rare in the history of art. While skillful execution requires prior practice and expertise, the creative act itself, springing from a more or less unselfconscious cultural and professional memory, might be quite autonomous and unpremeditated. A first affirmation of this hypothesis in the modern literature of art history occurred more than a century-and-a-half ago when one of the great French founding fathers of modern art history (especially the discipline of iconography), Adolphe Napoléon Didron, made a discovery that can be described, almost literally, as monumental. In the introduction to his publication — the first Greek-Byzantine treatise on painting, which he dedicated to his friend and enthusiastic fellow- medievalist, Victor Hugo — Didron gave a dramatic account of a moment of intellectual illumination that occurred during a pioneering exploratory visit to Greece in August and September 1839 for the purpose of studying the medieval fresco and mosaic decorations of the Byzantine churches.1 He had, he says, wondered at the uniformity and continuity of the Greek * This contribution is a much revised and expanded version of my original, brief sketch of the history of sculptors’ models, Irving Lavin, “Bozzetti and Modelli. -

Stories and Essays on Persephone and Medusa Isabelle George Rosett Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 Voices of Ancient Women: Stories and Essays on Persephone and Medusa Isabelle George Rosett Scripps College Recommended Citation Rosett, Isabelle George, "Voices of Ancient Women: Stories and Essays on Persephone and Medusa" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 1008. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1008 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOICES OF ANCIENT WOMEN: STORIES AND ESSAYS ON PERSEPHONE AND MEDUSA by ISABELLE GEORGE ROSETT SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR NOVY PROFESSOR BERENFELD APRIL 21, 2017 1 2 Dedicated: To Max, Leo, and Eli, for teaching me about surviving the things that scare me and changing the things that I can’t survive. To three generations of Heuston women and my honorary sisters Krissy and Madly, for teaching me about the ways I can be strong, for valuing me exactly as I am, and for the endless excellent desserts. To my mother, for absolutely everything (but especially for fielding literally dozens of phone calls as I struggled through this thesis). To Sam, for being the voice of reason that I happily ignore, for showing up with Gatorade the day after New Year’s shenanigans, and for the tax breaks. To my father (in spite of how utterly terrible he is at carrying on a phone conversation), for the hikes and the ski days, for quoting Yeats and Blake at the dinner table, and for telling me that every single essay I’ve ever asked him to edit “looks good” even when it was a blatant lie. -

Roma 1565-1578: Intorno a Cornelis Cort

©Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo-Bollettino d'Arte EVELI NA BOREA ROMA 1565-1578: INTORNO A CORNELIS CORT Notoriament6 nel suo soggiorno italiano Cornelis la composizione gigantesca di misurarsi con difficoltà Con operò a Venezia, Firenze, Roma, fra il 1565 e il assai diverse da quelle sino ad allora affrontate dai va 1578, anno di morte. Non ci sono ombre sulle sue at ri Vico, Fagiuoli, Bonasone, Beatrizet, dediti a ripro tività in quel periodo, le stampe da lui prodotte in durre i piccoli disegni cJi Perin del Vaga e Francesco quel tempo sono quasi tutte datate e il benemerito Salviati, o, in ogni caso, a tradurre in forma grafi ca, Bierens de Haan che le ha catalogate ne ha indicato come base per le incisioni, dipinti di dimensioni nor tlllte le connessioni con i modelli pittorici e grafi ci da mali. Fu allora che ne lle stamperie nacque l'idea di far cui derivano, con gli stampatori, nonché Le ristampe e comporre delle suites di stampe non assimilabili alle le copie che se ne trassero, a dimostrazione della for pagine di un libro, ciò che si faceva comunemente - a tu na ottenuta dal Cort stesso nel suo paese, in Italia e cominciare da Durer - , bensì come tasselli di forma in generale.'> irregolare rispecchianti singole parti della composizio ella recente mostra di Rotterdam il Sellink ha rag ne, numerati, da montarsi su tavole di legno per rico gruppato a parte un'antologia delle stampe italiane stituire l'immagine intera del 'Giudizio Universale' ed del Con , e pur mantenendo il criterio del raggruppa eventualmente di tutta la volta della Cappella Sistina.