Art, Argento and the Rape-Revenge Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering Il Bottaccio, Relais&Chateaux

DISCOVERING IL BOTTACCIO, RELAIS&CHATEAUX The setting for the dinner is at your choice: a romantic table in “Sala Diana” close to the fireplace, or on the border of the pool surrounded by “Bottaccio” is the place of the gathering of the waters created from the deviation unique pieces of art in “Sala della Piscina”, or you may choose for an open of rivers, fords and streams used in ancient times, to set into motion mill wheels. air dinner in our garden overlooking the ancient water mill wheel which is The maison, an original 18th century water wheel, opened its gates for the first still working. time in 1983 and is part of the international association of Relais & Chateaux since 1988. THE CUISINE Through the park runs a VII century Roman road that used to lead to the ruins of Aghinolfi Castle still overlooking Il Bottaccio. The D’Anna family entrusted Il Bottaccio to the Chef - Director Nino Mosca The dream of the D’Anna family was since the beginning to open a hotel for more than 35 years ago, and has watched it grow with passion to become not travellers that do not like hotels, so at Il Bottaccio you will feel just like home only an institution, but also a mecca for the devotees of fine Italian cuisine. In but with 5*****L service. Nino there is the precious gift of equilibrium, acquired from years of dedication, experience and introspection, which permits him to blend a DINING AT IL BOTTACCIO luminous creativity with the most profound roots of Italian tradition. -

Pictorial Imagery, Camerawork and Soundtrack in Dario Argento's Deep

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 11 (2015) 159–179 DOI: 10.1515/ausfm-2015-0021 Pictorial Imagery, Camerawork and Soundtrack in Dario Argento’s Deep Red Giulio L. Giusti 3HEFlELD(ALLAM5NIVERSITY5+ E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. This article re-engages with existing scholarship identifying Deep Red (Profondo rosso, 1975) as a typical example within Dario Argento’s body of work, in which the Italian horror-meister fully explores a distinguishing pairing of the acoustic and the iconic through an effective combination of ELABORATECAMERAWORKANDDISJUNCTIVEMUSICANDSOUND3PECIlCALLY THIS article seeks to complement these studies by arguing that such a stylistic and technical achievementINTHElLMISALSORENDEREDBY!RGENTOSUSEOFASPECIlC art-historical repertoire, which not only reiterates the Gesamtkunstwerk- like complexity of the director’s audiovisual spectacle, but also serves to TRANSPOSETHElLMSNARRATIVEOVERAMETANARRATIVEPLANETHROUGHPICTORIAL techniques and their possible interpretations. The purpose of this article is, thus, twofold. Firstly, I shall discuss how Argento’s references to American hyperrealism in painting are integrated into Deep Red’s spectacles of death through colour, framing, and lighting, as well as the extent to which such references allow us to undertake a more in-depth analysis of the director’s style in terms of referentiality and cinematic intermediality. Secondly, I WILLDEMONSTRATEHOWANDTOWHATEXTENTINTHElLM!RGENTOMANAGESTO break down the epistemological system of knowledge and to disrupt the reasonable -

One Touch of Venus Notes on a Cardiac Arrest at the Uffizi Ianick Takaes De Oliveira1

Figura: Studies on the Classical Tradition One touch of Venus Notes on a cardiac arrest at the Uffizi Ianick Takaes de Oliveira1 Submetido em: 15/04/2020 Aceito em: 11/05/2020 Publicado em: 01/06/2020 Abstract A recent cardiovascular event at the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence in December 2018 involving an elderly Tuscan male gathered significant media attention, being promptly reported as another case of the so-called Stendhal syndrome. The victim was at the Botticelli room the moment he lost consciousness, purportedly gazing at the Birth of Venus. Medical support was made immediately available, assuring the patient’s survival. Taking the 2018 cardiovascular event as a case study, this paper addresses the emergence of the Stendhal syndrome (as defined by the Florentine psychiatrist Graziella Magherini from the 1970s onwards) and similar worldwide syndromes, such as the Jerusalem, Paris, India, White House, and Rubens syndromes. Their congeniality and coevality speak in favor of their understanding as a set of interconnected phenomena made possible partly by the rise of global tourism and associated aesthetic- religious anxieties, partly by the migration of ideas concerning artistic experience in extremis. While media coverage and most art historical writings have discussed the Stendhal syndrome as a quizzical phenomenon – one which serves more or less to justify the belief in the “power of art” –, our purpose in this paper is to (1) question the etiological specificity of the Stendhal syndrome and, therefore, its appellation as such; (2) argue in favor of a more precise neuroesthetic explanation for the incident at the Uffizi; (3) raise questions about the fraught connection between health-related events caused by artworks and the aesthetic experience. -

Pictorial Real, Historical Intermedial. Digital Aesthetics and the Representation of History in Eric Rohmer's the Lady And

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 12 (2016) 27–44 DOI: 10.1515/ausfm-2016-0002 Pictorial Real, Historical Intermedial. Digital Aesthetics and the Representation of History in Eric Rohmer’s The Lady and the Duke Giacomo Tagliani University of Siena (Italy) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In The Lady and the Duke (2001), Eric Rohmer provides an unusual and “conservative” account of the French Revolution by recurring to classical and yet “revolutionary” means. The interpolation between painting and film produces a visual surface which pursues a paradoxical effect of immediacy and verisimilitude. At the same time though, it underscores the represented nature of the images in a complex dynamic of “reality effect” and critical meta-discourse. The aim of this paper is the analysis of the main discursive strategies deployed by the film to disclose an intermedial effectiveness in the light of its original digital aesthetics. Furthermore, it focuses on the problematic relationship between image and reality, deliberately addressed by Rohmer through the dichotomy simulation/illusion. Finally, drawing on the works of Louis Marin, it deals with the representation of history and the related ideology, in order to point out the film’s paradoxical nature, caught in an undecidability between past and present. Keywords: Eric Rohmer, simulation, illusion, history and discourse, intermediality, tableau vivant. The representation of the past is one of the domains, where the improvement of new technologies can effectively disclose its power in fulfilling our “thirst for reality.” No more cardboard architectures nor polystyrene stones: virtual environments and motion capture succeed nowadays in conveying a truly believable reconstruction of distant times and worlds. -

Xavier Aldana Reyes, 'The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror

1 Originally published in/as: Xavier Aldana Reyes, ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’, Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies, 5.2 (2017), 229–44. DOI link: 10.1386/jicms.5.2.229_1 Title: ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’ Author: Xavier Aldana Reyes Affiliation: Manchester Metropolitan University Abstract: Dario Argento is the best-known living Italian horror director, but despite this his career is perceived to be at an all-time low. I propose that the nadir of Argento’s filmography coincides, in part, with his embrace of the gothic adaptation and that at least two of his late films, The Phantom of the Opera (1998) and Dracula 3D (2012), are born out of the tensions between his desire to achieve auteur status by choosing respectable and literary sources as his primary material and the bloody and excessive nature of the product that he has come to be known for. My contention is that to understand the role that these films play within the director’s oeuvre, as well as their negative reception among critics, it is crucial to consider how they negotiate the dichotomy between the positive critical discourse currently surrounding gothic cinema and the negative one applied to visceral horror. Keywords: Dario Argento, Gothic, adaptation, horror, cultural capital, auteurism, Dracula, Phantom of the Opera Dario Argento is, arguably, the best-known living Italian horror director. -

Jan Lievens (Leiden 1607 – 1674 Amsterdam)

Jan Lievens (Leiden 1607 – 1674 Amsterdam) © 2017 The Leiden Collection Jan Lievens Page 2 of 11 How To Cite Bakker, Piet. "Jan Lievens." In The Leiden Collection Catalogue. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017. https://www.theleidencollection.com/archive/. This page is available on the site's Archive. PDF of every version of this page is available on the Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. Archival copies will never be deleted. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. Jan Lievens was born in Leiden on 24 October 1607. His parents were Lieven Hendricxsz, “a skillful embroiderer,” and Machtelt Jansdr van Noortsant. 1 The couple would have eight children, of whom Jan and Dirck (1612–50/51) would become painters, and Joost (Justus), the eldest son, a bookseller. 2 In 1632 Joost married an aunt of the painter Jan Steen (1625/26–79). 3 At the age of eight, Lievens was apprenticed to Joris van Schooten (ca. 1587–ca. 1653), “who painted well [and] from whom he learned the rudiments of both drawing and painting.” 4 According to Orlers, Lievens left for Amsterdam two years later in 1617 to further his education with the celebrated history painter Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), “with whom he stayed for about two years making great progress in art.” 5 What impelled his parents to send him to Amsterdam at such a young age is not known. When he returned to Leiden in 1619, barely twelve years old, “he established himself thereafter, without any other master, in his father’s house.” 6 In the years that followed, Lievens painted large, mostly religious and allegorical scenes. -

Radiocorrieretv SETTIMANALE DELLA RAI RADIOTELEVISIONE

RadiocorriereTv SETTIMANALE DELLA RAI RADIOTELEVISIONE ITALIANA numero 10 - anno 90 8 marzo 2021 Reg. Trib. n. 673 del 16 dicembre 1997 MANESKIN TRIONFO ROCK ©Maurizio D'Avanzo NELLE LIBRERIE E STORE DIGITALI Nelle librerie e store digitali 2 TV RADIOCORRIERE 3 3 Nelle librerie PERCHE’ SANREMO e store digitali È SANREMO Sanremo è finito. Viva Sanremo. Come ogni anno ci sono vincitori e vinti, ci sono critiche e commenti, applausi e fischi, anche in questa edizione da remoto. Poi ci sono loro. I dipendenti di questa azienda, a volte bistrattata, ma sempre presenti, con forza, capacità e soprattutto con tanta dignità. E allora grazie a tutte, ma proprio tutte, le maestranze della Rai che ancora una volta hanno messo in campo tutto quello che potevano lavorando anche in condizioni di grandissima difficoltà. Grazie a chi ha lasciato per settimane i propri affetti, in questo periodo non era facile, per trasferirsi a lavorare in una città molto diversa da quella glamour e festante degli anni passati. Un lavoro certosino, meticoloso come sempre, solo come quello che i tecnici e giornalisti Rai sanno fare quando sono chiamati a giocare finali. Questo Festival ha portato rispetto e forse non lo ha ricevuto del tutto. Non era facile calarsi con garbo in un periodo fatto di sofferenze e paure. Cercare di entrare nelle case degli italiani spaventati. Per una settimana si è provato a far riscoprire quel desiderio di normalità misto a fiducia. Cinque serate di evasione, di riflessione, ma anche di speranza che il mondo della musica, dello spettacolo, possano tornare quanto prima a regalare emozioni. -

© 2018 Donata Panizza ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2018 Donata Panizza ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OVEREXPOSING FLORENCE: JOURNEYS THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHY, CINEMA, TOURISM, AND URBAN SPACE by DONATA PANIZZA A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Italian Written under the direction of Professor Rhiannon Noel Welch And approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey OCTOBER, 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Overexposing Florence: Journeys through Photography, Cinema, Tourism, and Urban Space by DONATA PANIZZA Dissertation Director Rhiannon Noel Welch This dissertation examines the many ways in which urban form and visual media interact in 19th-, 20th-, and 21st-centuries Florence. More in detail, this work analyzes photographs of Florence’s medieval and Renaissance heritage by the Alinari Brothers atelier (1852- 1890), and then retraces these photographs’ relationship to contemporary visual culture – namely through representations of Florence in international cinema, art photography, and the guidebook – as well as to the city’s actual structure. Unlike previous scholarship, my research places the Alinari Brothers’ photographs in the context of the enigmatic processes of urban modernization that took place in Florence throughout the 19th century, changing its medieval structure into that of a modern city and the capital of newly unified Italy from 1865 to 1871. The Alinari photographs’ tension between the establishment of the myth of Florence as the cradle of the Renaissance and an uneasy attitude towards modernization, both cherished and feared, produced a multi-layered city portrait, which raises questions about crucial issues such as urban heritage preservation, mass tourism, (de)industrialization, social segregation, and real estate speculation. -

La Giuria Di X Factor 2018: Fedez, Mara Maionchi

MARTEDì 29 MAGGIO 2018 X Factor 2018 ha la sua giuria: saranno Fedez, Mara Maionchi, Manuel Agnelli e Asia Argentoa sedere al tavolo della prossima edizione del talent show di Sky, prodotto da FremantleMedia Italia. Confermatissimo La giuria di X Factor 2018: Fedez, alla conduzione Alessandro Cattelan. Mara Maionchi, Manuel Agnelli e Asia Argento "Siamo molto felici di ritrovare Fedez a Mara, due fuoriclasse il cui ritorno era confermato da qualche tempo, e molto soddisfatti che Manuel si sia convinto a non prendersi una pausa e rinnovare il suo impegno in questa grande avventura, una presenza, la sua, della quale X Factor non può fare ANTONIO GALLUZZO a meno dopo l'eccellente lavoro fatto in questi due anni - ha dichiarato Nils Hartmann, Direttore produzioni originali di Sky Italia. E siamo entusiasti di dare il benvenuto ad Asia nella famiglia di X Factor, dove siamo certi che il contributo della sua cultura musicale e personalità sarà importantissimo. Asia con Fedez, Mara e Manuel comporranno una straordinaria nuova squadra capace di individuare e coltivare le [email protected] potenzialità dei talenti che incontreranno. SPETTACOLINEWS.IT Alessandro Cattelan con il suo talento saprà poi, ancora una volta, garantire uno straordinario ritmo allo show" "Diamo il benvenuto a tutti i protagonisti di questa nuova edizione, e in particolare ad Asia Argento, che siamo felicissimi di avere a bordo. - ha affermato Gabriele Immirzi, Direttore Generale FremantleMedia Italia - X Factor 2018 inizia nel segno di un ulteriore rinnovamento creativo e produttivo, con l'ambizione di continuare a crescere ed essere sempre di più il punto riferimento degli show musicali italiani e internazionali" Asia si appresta così ad affrontare una nuova sfida, nella sua pluridecennale e multiforme carriera ha spaziato dal cinema, dove è regista e autrice, alla tv, e alla musica, con una visione unica, spaziando nel mondo industrial ed elettropop. -

Beyond Stendhal: Emotional Worlds Or Emotional Tourists? Mike Robinson

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals... Beyond Stendhal: Emotional Worlds or Emotional Tourists? Mike Robinson Introduction Some years ago I visited the World Heritage Site of Petra in Jordan, the ancient Nabatean City built into encircling red sandstone cliffs. 1 Without any detailed knowledge of the Nabateans and their place in the history of the region, it is clearly an impressive place by virtue of its scale, by virtue of the craft of its construction and, particularly, by virtue of its seeming seclusion. I was especially struck by the way the site seems to have its own physical narrative, which blends the natural features of the deeply gorged cliffs with the creativity of its sixth century BCE founders in striving to hide this city from the rest of the world, and, also, the creativity of those who have long recognised the allure of the place to visitors. For most visitors, to reach this ancient site you have to walk, and the walk takes you from a relatively commonplace and bustling entrance of open, rough and stony land which promises little, through a high- sided and, at times, claustrophobic narrow gorge – known as the ‘siq’ – to a position where your sight is drawn from bare wall and dusty ground to a powerful vision; a true glimpse into another world. For as one moves out of the siq, one is faced with the sheer power of a monument; the magnificent façade of what is known as the Treasury, carved out of, and into, the solid wall of the high cliffs. -

Post-Cinematic Affect: on Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales

Film-Philosophy 14.1 2010 Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales Steven Shaviro Wayne State University Introduction In this text, I look at three recent media productions – two films and a music video – that reflect, in particularly radical and cogent ways, upon the world we live in today. Olivier Assayas’ Boarding Gate (starring Asia Argento) and Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales (with Justin Timberlake, Dwayne Johnson, Seann William Scott, and Sarah Michelle Gellar) were both released in 2007. Nick Hooker’s music video for Grace Jones’s song ‘Corporate Cannibal’ was released (as was the song itself) in 2008. These works are quite different from one another, in form as well as content. ‘Corporate Cannibal’ is a digital production that has little in common with traditional film. Boarding Gate, on the other hand, is not a digital work; it is thoroughly cinematic, in terms both of technology, and of narrative development and character presentation. Southland Tales lies somewhat in between the other two. It is grounded in the formal techniques of television, video, and digital media, rather than those of film; but its grand ambitions are very much those of a big-screen movie. Nonetheless, despite their evident differences, all three of these works express, and exemplify, the ‘structure of feeling’ that I would like to call (for want of a better phrase) post-cinematic affect. Film-Philosophy | ISSN: 1466-4615 1 Film-Philosophy 14.1 2010 Why ‘post-cinematic’? Film gave way to television as a ‘cultural dominant’ a long time ago, in the mid-twentieth century; and television in turn has given way in recent years to computer- and network-based, and digitally generated, ‘new media.’ Film itself has not disappeared, of course; but filmmaking has been transformed, over the past two decades, from an analogue process to a heavily digitised one. -

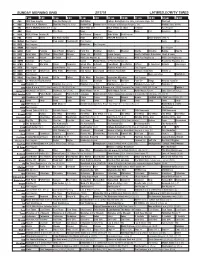

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min.