Southern California Airport Exploratory Study 2.0 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

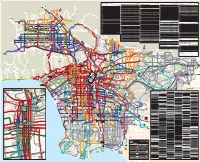

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

“Ablueprintforbuildingonesandiego”

“A Blueprint for Building One San Diego” Mayor Kevin L. Faulconer 1 TRANSITION ADVISORY COMMITTEE RECOMMENDATIONS June 12, 2014 The Office of the Mayor would like to thank the following members of the One San Diego Transition Advisory Committee for volunteering their time to reviewing materials, attending meetings and providing valuable input for this report. ONE SAN DIEGO TRANSITION ADVISORY COMMITTEE CHAIRS Stephen Cushman Tony Young MEMBERS Susie Baumann Ben Katz Faith Bautista Leslie Kilpatrick Sam Bedwell Ure Kretowicz Blanca Lopez Brown Pastor Rick Laster Mark Cafferty Elyse Lowe Dr. Constance M. Carroll Lani Lutar Father Joe Carroll William D. Lynch Sharon Cloward Tony Manolatos Byeong Dae Kim Cindy Marten Aimee Faucett Brian Marvel Randy Frisch Vincent E. Mudd Ronne Froman Nicole Murray-Ramirez Gary Gallegos Bob Nelson Rick Gentry Joseph D. Panetta Bill Geppert Dan Stoneman Robert Gleason Russ Thurman Jeff Graham Rick Valencia Abdur-Rahim Hameed Kristen Victor Dan Hom Reverend Walter G. Wells Jennifer Jacobs Faye Wilson Tracy Jarman Christopher Yanov Susan Jester Barbara Ybarra Jeff Johnson Michael Zucchet 2 ONE SAN DIEGO TRANSITION ADVISORY COMMITTEE Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................. 4 Subcommittee Reports ............................................................................. 7 Education & Youth Opportunity ............................................................ 7 Homeless & Housing Affordability ................................................... -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

11-07-19-Board-Packet-1.Pdf

Long Beach Transit welcomes you to this meeting and invites you to participate in matters before the Board. Information and Procedures Concerning Conduct at Board of Directors’ Meetings PUBLIC PARTICIPATION: SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS: All members of the public may address the Board on any Special presentations which include slides, video, etc., item listed on the agenda. during the course of a meeting will only be allowed when All members of the public may address the Board on non- requested of the Board Secretary eight days in advance of agenda items from “Business From The Floor.” the meeting, which will require prior approval from the Chair. Each speaker will be asked to complete a Speaker Card and turn it in to the Board Secretary prior to the conclusion BUSINESS FROM THE FLOOR: of the staff presentation and will state his/her name at the podium before speaking. A member of the general public may address the Board on any matter not appearing on the agenda that is of interest Persons demonstrating rude, bois- to such person and within the jurisdiction of the terous or profane behavior will be Board. called to order by the Chair. If such conduct continues, the Chair may No action can be taken by the Board on any call a recess, requesting the removal The Board of Directors items brought forward at this time. The Board of such person(s) from the Council and Staff shall work to may request this item be brought back at a Chamber, adjourn the meeting or subsequent meeting. take some other appropriate action. -

Long Beach Transit and Flixbus Partner to Provide Affordable, Long-Distance Transportation New Service to Las Vegas Starts March 21

CONTACT: Michael Gold Public Information Officer, Long Beach Transit 562.599.8534 (office) 562.444.5309 (cell) [email protected] Julie Alvarez, FlixBus 213.378.3917 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Long Beach Transit and FlixBus Partner to Provide Affordable, Long-Distance Transportation New Service to Las Vegas starts March 21 LONG BEACH, CALIF. (March 14, 2018) – Long Beach Transit today announced a partnership with FlixBus to provide affordable bus service to Las Vegas starting March 21. FlixBus, a European-based mobility company, selected Long Beach as one of its hubs for travel to add to its growing network of destinations. “Long Beach impressed us with its diversity, energy and very progressive transit policy. It’s probably the most FlixBus-compatible community in California,” said Pierre Gourdain, Managing Director for FlixBus USA. “We are thrilled to start the route there and looking to add many more connections in the future.” Utilizing LBT’s downtown First Street Transit Gallery between Long Beach Blvd. and Pine Avenue, customers can take FlixBus to Las Vegas by purchasing tickets through the FlixBus app or website. Customers can also buy tickets at LBT’s Transit and Visitor Information Center. FlixBus will also offer service to Coachella and Stagecoach music festivals in April. “Our partnership with FlixBus is another example of LBT connecting communities, both locally and beyond,” said LBT President and CEO, Kenneth McDonald. “Now, LBT customers can catch a bus to the Transit Gallery and then explore destinations outside California.” Most of LBT’s buses connect to the Transit Gallery. In addition, customers can connect to other destinations outside the area through the Los Angeles Metro Blue Line, FlyAway service to Los Angeles International Airport and through connections to Long Beach Airport. -

City Council Agenda Consideration for Passenger Flights in And

RANCHO PALOS VERDES CITY COUNCIL MEETING DATE: 05/07/2019 AGENDA REPORT AGENDA HEADING: Consent Calendar AGENDA DESCRIPTION: Consideration and possible action to enter into a Professional Services Agreement with ABCx2, LLC to analyze passenger jets flights over and around the Rancho Palos Verdes airspace RECOMMENDED COUNCIL ACTION: (1) Approve a Professional Services Agreement with ABCx2, LLC in the amount of $30,500 to analyze passenger jets flights over and around the Rancho Palos Verdes airspace FISCAL IMPACT: The services provided under this contract shall not exceed $30,500, including no more than $3,000 for reimbursable expenses, and has been budgeted in the Planning Division’s Professional and Technical Services account. Amount Budgeted: $193,825 Additional Appropriation: N/A Account Number(s): 101-400-4120-5101 (GF – Professional/Technical Services in Planning Division) ORIGINATED BY: Robert Nemeth, Associate Planner REVIEWED BY: Ara Mihranian, AICP, Director of Community Development APPROVED BY: Doug Willmore, City Manager ATTACHED SUPPORTING DOCUMENTS: A. Professional Services Agreement between City of Rancho Palos Verdes and ABCx2, LLC (page A-1) B. ABCx2, LLC Proposal to Rancho Palos Verdes (page B-1) C. May 30, 2018 City Attorney letter to FAA (page C-1) D. July 13, 2018 FAA response letter to City Attorney (page D-1) BACKGROUND AND DISCUSSION: In March 2017, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) implemented its SoCal Metroplex project, which was a regional redesign of the airspace over Southern California. With respect to passenger jet departures from Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), the SoCal Metroplex project did not change established offshore flight routes near the Palos Verdes Peninsula. -

363 Part 238—Contracts With

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

March 2018 REFLECTIONS the Newsletter of the Northwest Airlines History Center Dedicated to Preserving the History of a Great Airline and Its People

Vol.16, no.1 nwahistory.org facebook.com/NorthwestAirlinesHistoryCenter March 2018 REFLECTIONS The Newsletter of the Northwest Airlines History Center Dedicated to preserving the history of a great airline and its people. NORTHWEST AIRLINES 1926-2010 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ THE QUEEN OF THE SKIES Personal Retrospectives by Robert DuBert It's hard to believe that they are gone. Can it be possible that it was 50 years ago this September that this aircraft made its first public appearance? Are we really all so, ahem, elderly that we Photo: True Brand, courtesy Vincent Carrà remember 1968 as if it were yesterday? This plane had its origins in 1964, when Boeing began work on a proposal for the C-5A large military airlifter contract, and after Lockheed won that contest, Boeing considered a commercial passenger version as a means of salvaging the program. Urged on by Pan Am president Juan Trippe, Boeing in 1965 assigned a team headed by Chief Engineer Joe Sutter to design a large new airliner, although Boeing at the time was really more focused on its supersonic transport (SST) program. A launch customer order from Pan Am on April 13, 1966 for twenty five aircraft pushed Sutter's program into high gear, and in a truly herculian effort, Joe Sutter and his Boeing team, dubbed “The Incredibles,” brought the program from inception on paper to the public unveiling of a finished aircraft in the then unheard of time of 29 months. We're talking, of course, about the legendary and incomparable Boeing 747. THE ROLLOUT It was a bright, sunny morning on Monday, Sept. -

Ilg National Conference Transportation – Anaheim, Ca

ILG NATIONAL CONFERENCE TRANSPORTATION – ANAHEIM, CA AIR TRANSPORTATION: John Wayne Airport, Orange County (SNA) – 14.1 miles to Anaheim Marriott Convention Center http://www.ocair.com Airlines serving John Wayne Airport: • Alaska Airlines • American Airlines • Delta Air Lines • Frontier Airlines • Southwest Airlines • United Airlines • WestJet Long Beach Airport (LGB) – 18.2 miles to Anaheim Marriott Convention Center http://www.lgb.org Airlines service Long Beach Airport: • American Airlines • Delta Air Lines • JetBlue • Southwest Airlines Ontario International Airport (ONT) – 30.8 miles to Anaheim Marriott Convention Center https://www.flyontario.com/ Airlines service Long Beach Airport: • Alaska • American Airlines • Delta Air Lines • Frontier Airlines • Southwest Airlines • United Airlines • Volaris Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) – 35 miles to Anaheim Marriott Convention Center http://www.lawa.org 59 airlines service Los Angeles International Airport Please Note: The information contained in this document is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement of any product or services. 2018 ILG National Conference Page 2 of 5 Transportation-Anaheim SHUTTLE/SHARED RIDE SERVICES: *Remember to inquire about AAA discounts Airvan Transport, LLC http://www.airvantransport.com (909) 224-7826 Airports Served: • Long Beach Airport (LGB) • Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) • Ontario International Airport (ONT) • Orange County-John Wayne (SNA) AMPM Shuttle http://www.ampmshuttle.com (949) 678-4549 -

Air Traffic Demand Forecast

Special Assistance for Project Implementation (SAPI) for Borg El Arab International Airport Modernization Project - Final Report - Chapter 4 Air Traffic Demand Forecast Table of Contents 4.1 Review of SAPROF Study ................................................................................................... 4-1 4.1.1 Procedure of Air Traffic Demand Forecast applied in SAPROF ................................ 4-1 4.1.2 Comparison between the Forecast in SAPROF Study with the actual Traffic ............ 4-2 4.1.3 Comparative Analysis between SAPROF and Present ............................................... 4-4 4.1.4 Principal Conclusion ................................................................................................... 4-7 4.2 Forecasting Parameters ....................................................................................................... 4-8 4.2.1 Air Traffic in Egypt ..................................................................................................... 4-8 4.2.2 Origin & Destination / Nationality of Air Passenger ................................................ 4-13 4.2.3 Trend of Scheduled Flights in Alexandria ................................................................. 4-16 4.2.4 Passenger Survey at Borg El Arab International Airport .......................................... 4-20 4.2.5 Socio-Economic Indices ........................................................................................... 4-29 4.3 Annual Passenger Demand Forecast ............................................................................... -

City of Phoenix Aviation Department Sky Harbor International Airport Financial Management Division Monthly Statistical Reports - November 2016 Table of Contents

City of Phoenix Aviation Department Sky Harbor International Airport Financial Management Division Monthly Statistical Reports - November 2016 Table of Contents Reports: Graphs: 1 Passengers, Cargo, and Aircraft Operations 1 Domestic Enplaned I Deplaned Passengers Terminal 2 2 Passenger Activity Report 2 Domestic Enplaned I Deplaned Passengers Terminal 3 3 Passenger and Activity Worksheet November 2016 3 Domestic Enplaned I Deplaned Passengers Terminal 4 4 Passenger and Activity Worksheet November 2015 4 Total Domestic Enplaned I Deplaned Passengers 5 Enplaned Passengers by Carrier for Fiscal Year 2016/17 5 Total International Enplaned I Deplaned Passengers 6 Deplaned Passengers by Carrier for Fiscal Year 2016/17 6 Total Enplaned I Deplaned Passengers 7 Total Passengers by Carrier for Fiscal Year 2016/17 7 Total Enplaned I Deplaned Cargo (in Tons) 8 Enplaned Passengers by Carrier for Calendar Year 2016 8 Sky Harbor International Airport Aircraft Operations 9 Deplaned Passengers by Carrier for Calendar Year 2016 9 Deer Valley Airport Aircraft Operations 10 Total Passengers by Carrier for Calendar Year 2016 1O Goodyear Airport Aircraft Operations 11 Airline Landing Weights -All Airlines for Fiscal Year 2016/17 12 Airline Landing Weights - Rates & Charges Airlines Only for Fiscal Year 2016/17 PASSENGERS, CARGO, AND AIRCRAFT OPERATIONS AT PHOENIX AIRPORTS: November 2016 Fis cal YTD Fis ca l YTD Calenda r YTD ___ _ _._ 2016 2015 %Cha ___. _. ___._. __ %Chg I I 201 6 T2 153,849 149,936 2.6% 646,914 592,535 9.2% 1,585,013 1,359,302 16.6% T3 -

Anarchy in the Airways Joseph C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@Florida International University Hospitality Review Volume 5 Article 10 Issue 1 Hospitality Review Volume 5/Issue 1 1-1-1987 Anarchy In The Airways Joseph C. Von Kornfeld University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/hospitalityreview Recommended Citation Von Kornfeld, Joseph C. (1987) "Anarchy In The Airways," Hospitality Review: Vol. 5: Iss. 1, Article 10. Available at: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/hospitalityreview/vol5/iss1/10 This work is brought to you for free and open access by FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hospitality Review by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anarchy In The Airways Abstract In his dialogue - Anarchy In The Airways - Joseph C. Von Kornfeld, Assistant Professor, College of Hotel Administration, University of Nevada, Las Vegas initially states: “Deregulation of the airline industry has brought about financial vulnerability for the traveling public. The uthora analyzes the situation since that point in time and makes recommendations for some solutions.” In this article, Assistant Professor Von Kornfeld, first defines the airline industry in its pre-regulated form. Then he goes into the ramifications and results of deregulating the industry, both in regards to the consumer, and in deregulation’s impact on the airlines themselves. “The most dramatic consequence of the pressures and turbulence of airline deregulation has been the unprecedented proliferation of airline bankruptcies,” Von Kornfeld informs.