Changing Paradigms in Management of Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (Mcrpc) Eva Gupta1*, Troy Guthrie2 and Winston Tan1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Phase 1 Multiple-Dose Study of Orteronel in Japanese Patients with Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol (2015) 75:373–380 DOI 10.1007/s00280-014-2654-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE A phase 1 multiple-dose study of orteronel in Japanese patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer Kazuhiro Suzuki · Seiichiro Ozono · Akito Yamaguchi · Hidekazu Koike · Hiroshi Matsui · Masao Nagata · Takatoshi Takubo · Kana Miyashita · Takafumi Matsushima · Hideyuki Akaza Received: 6 November 2014 / Accepted: 14 December 2014 / Published online: 24 December 2014 © The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Cycle 1 in this study. Adverse events (AEs) were reported Purpose Orteronel (TAK-700) is a non-steroidal, selec- in all 15 patients. Most common AEs (>30 %) were hyper- tive, reversible inhibitor of 17,20-lyase. We evaluated the lipasemia (47 %), hyperamylasemia (40 %), and consti- safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, pation (33 %). Acute pancreatitis (Grades 2 and 3) and and antitumor effect of orteronel with or without predniso- pancreatitis (Grade 1) were complicated in three patients lone in Japanese patients with castration-resistant prostate during the study. Dose-dependent increase in plasma orte- cancer (CRPC). ronel concentrations was indicated over the 200–400 mg Methods We conducted a phase 1 study in men with pro- BID dose range. Prednisolone coadministered did not alter gressive and chemotherapy-naïve CRPC. Patients received PK of orteronel. Serum testosterone was rapidly suppressed orteronel orally at doses of 200–400 mg twice daily (BID) below the lower limit of quantification across all doses. Of with or without oral prednisolone (5 mg BID). Dose-limit- 15 subjects, 13 achieved at least a 50 % reduction from ing toxicity (DLT) was assessed during Cycle 1 (28 days). -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (Io) Pub

llIIlIlllIlIlIllIlIllIllIllIIlIlllIlIIllllIIlllIIlIlllIIlIlllllIIIlllIlIllIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII US 20160015712AI (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (Io) Pub. No. : US 2016/0015712 A1 DORSCH et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 21, 2016 (54) TRIAZOLO [4,5-D]PYRIMIDINE Publication Classification DERIVATIVES (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: MERCK PATENT GMBH, Darmstadt 261K31/519 (2006.01) (DE) 261K31/53 77 (2006.01) C07D 519/00 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Dieter DORSCH, Ober-Ramstadt (DE); C07D 487/04 (2006.01) Guenter HOELZEMANN, (52) U.S. Cl. Seeheim- Jugenheim (DE); Michel CPC ............ 261K31/519 (2013.01); C07D 487/04 CALDERINI, Darmstadt (DE); Ansgar (2013.01);261K31/5377 (2013.01); C07D WEGENER, Heusenstamm (DE); 519/00 (2013.01) Oliver POESCHKE, Wiesbaden (DE) (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: MERCK PATENT GMBH, Darmstadt (DE) Compounds of the formula I (21) Appl. No. : 14/772, 865 (22) PCT Filed: Feb. 10, 2014 H (86) PCT No. : PCT/EP2014/000361 II ) 371 (c)(I), NX N (2) Date: Sep. 4, 2015 (30) Foreign Application Priority Data in which R' and R have the meanings indicated in Claim 1, are inhibitors of GCN2, and can be employed, inter alia, for Mar. 5, 2013 (EP) ... 13001110.9 the treatment of cancer. US 2016/0015712 A1 Jan. 21, 2016 TRIAZOLO [4,5-D]PYRIMIDINE [0006] Several mechanistic studies discovered that DERIVATIVES immune escape has an important interface with metabolic alterations within the tumor microenvironment. Here impor- BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION tant roles in mediating immune tolerance to antigens have been associated to the catabolism ofthe essential amino acids [0001] The invention had the object of finding novel com- tryptophan and arginine, carried out by the enzymes pounds having valuable properties, in particular those which indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and arginase I (ARG), can be used for the medicaments. -

Galeterone for the Treatment of Castration- Resistant Prostate Cancer Bruce Montgomery1, Mario A

Published OnlineFirst November 2, 2015; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1432 Cancer Therapy: Clinical Clinical Cancer Research Androgen Receptor Modulation Optimized for Response (ARMOR) Phase I and II Studies: Galeterone for the Treatment of Castration- Resistant Prostate Cancer Bruce Montgomery1, Mario A. Eisenberger2, Matthew B. Rettig3, Franklin Chu4, Roberto Pili5, Joseph J. Stephenson6, Nicholas J. Vogelzang7, Alan J. Koletsky8, Luke T. Nordquist9, William J. Edenfield10, Khalid Mamlouk11, Karen J. Ferrante11, and Mary-Ellen Taplin12 Abstract Purpose: Galeterone is a selective, multitargeted agent that Results: In ARMOR1, across all doses, 49.0% (24/49) achieved a inhibits CYP17, antagonizes the androgen receptor (AR), and 30% decline in prostate-specific antigen (PSA; PSA30) and reduces AR expression in prostate cancer cells by causing an 22.4% (11/49) demonstrated a 50% PSA decline (PSA50). In increase in AR protein degradation. These open-label phase I ARMOR2 part 1, across all doses, PSA30 was 64.0% (16/25) and and II studies [Androgen Receptor Modulation Optimized PSA50 was 48.0% (12/25). In the 2,550-mg dose cohort, PSA30 for Response-1 (ARMOR1) and ARMOR2 part 1] evaluated was 72.7% (8/11) and PSA50 was 54.5% (6/11). Galeterone was the efficacy and safety of galeterone in patients with treat- well tolerated; the most common adverse events were fatigue, ment-naive nonmetastatic or metastatic castration-resistant increased liver enzymes, gastrointestinal events, and pruritus. Most prostate cancer (CRPC) and established a dose for further were mild or moderate in severity and required no action and there study. were no apparent mineralocorticoid excess (AME) events. -

WO 2018/111890 Al 21 June 2018 (21.06.2018) W !P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2018/111890 Al 21 June 2018 (21.06.2018) W !P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, C07K 16/28 (2006.01) A61K 31/4166 (2006.01) MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, 59/595 (2006.01) TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, KM, ML, MR, NE, SN, TD, TG). (21) International Application Number: PCT/US20 17/065841 Declarations under Rule 4.17: (22) International Filing Date: — as to applicant's entitlement to apply for and be granted a 12 December 2017 (12.12.2017) patent (Rule 4.1 7(H)) — as to the applicant's entitlement to claim the priority of the (25) Filing Language: English earlier application (Rule 4.17(Hi)) (26) Publication Langi English — of inventorship (Rule 4.1 7(iv)) (30) Priority Data: Published: 62/433,158 12 December 2016 (12.12.2016) US — with international search report (Art. 21(3)) — with sequence listing part of description (Rule 5.2(a)) (71) Applicant (for all designated States except AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CN, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IN, IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, P T RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TR): GENENTECH, INC. [US/US]; 1 DNA Way, South San Francisco, CA 94080-4990 (US). -

Tanibirumab (CUI C3490677) Add to Cart

5/17/2018 NCI Metathesaurus Contains Exact Match Begins With Name Code Property Relationship Source ALL Advanced Search NCIm Version: 201706 Version 2.8 (using LexEVS 6.5) Home | NCIt Hierarchy | Sources | Help Suggest changes to this concept Tanibirumab (CUI C3490677) Add to Cart Table of Contents Terms & Properties Synonym Details Relationships By Source Terms & Properties Concept Unique Identifier (CUI): C3490677 NCI Thesaurus Code: C102877 (see NCI Thesaurus info) Semantic Type: Immunologic Factor Semantic Type: Amino Acid, Peptide, or Protein Semantic Type: Pharmacologic Substance NCIt Definition: A fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), with potential antiangiogenic activity. Upon administration, tanibirumab specifically binds to VEGFR2, thereby preventing the binding of its ligand VEGF. This may result in the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and a decrease in tumor nutrient supply. VEGFR2 is a pro-angiogenic growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase expressed by endothelial cells, while VEGF is overexpressed in many tumors and is correlated to tumor progression. PDQ Definition: A fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), with potential antiangiogenic activity. Upon administration, tanibirumab specifically binds to VEGFR2, thereby preventing the binding of its ligand VEGF. This may result in the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and a decrease in tumor nutrient supply. VEGFR2 is a pro-angiogenic growth factor receptor -

Download Product Insert (PDF)

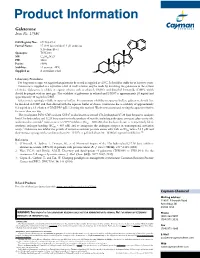

Product Information Galeterone Item No. 17586 N CAS Registry No.: 851983-85-2 Formal Name: 17-(1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)-androsta- 5,16-dien-3β-ol N Synonym: TOK-001 MF: C26H32N2O FW: 388.6 H Purity: ≥98% H H Stability: ≥2 years at -20°C Supplied as: A crystalline solid HO Laboratory Procedures For long term storage, we suggest that galeterone be stored as supplied at -20°C. It should be stable for at least two years. Galeterone is supplied as a crystalline solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the galeterone in the solvent of choice. Galeterone is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol, DMSO, and dimethyl formamide (DMF), which should be purged with an inert gas. The solubility of galeterone in ethanol and DMSO is approximately 20 mg/ml and approximately 30 mg/ml in DMF. Galeterone is sparingly soluble in aqueous buffers. For maximum solubility in aqueous buffers, galeterone should first be dissolved in DMF and then diluted with the aqueous buffer of choice. Galeterone has a solubility of approximately 0.2 mg/ml in a 1:3 solution of DMF:PBS (pH 7.2) using this method. We do not recommend storing the aqueous solution for more than one day. The cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoform CYP17 is also known as steroid 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase because it catalyzes both 17α-hydroxylase and 17,20 lyase reactions in the synthesis of steroids, including androgens, estrogens, glucocorticoids, 1 and mineralocorticoids. Galeterone is a CYP17 inhibitor (IC50 = 300 nM) that has been shown to competitively block synthetic androgen binding (EC50 = 845 nM) and to antagonize the androgen receptor in transcriptional activation 2 assays. -

Therapies Targeted to Androgen Receptor Signaling Axis in Prostate Cancer: Progress, Challenges, and Hope

cancers Review Therapies Targeted to Androgen Receptor Signaling Axis in Prostate Cancer: Progress, Challenges, and Hope Sirin Saranyutanon 1,2, Sanjeev Kumar Srivastava 1,2,*, Sachin Pai 3, Seema Singh 1,2,4 and Ajay Pratap Singh 1,2,4,* 1 Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL 36617, USA; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 Department of Oncologic Sciences, Mitchell Cancer Institute, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL 36604, USA 3 Department of Medical Oncology, Mitchell Cancer Institute, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL 36604, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL 36688, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.K.S.); [email protected] (A.P.S.); Tel.: +1-251-445-9874 (S.K.S.); +1-251-445-9843 (A.P.S.) Received: 4 November 2019; Accepted: 18 December 2019; Published: 23 December 2019 Abstract: Prostate cancer is the mostly commonly diagnosed non-cutaneous malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related death affecting men in the United States. Moreover, it disproportionately affects the men of African origin, who exhibit significantly greater incidence and mortality as compared to the men of European origin. Since androgens play an important role in the growth of normal prostate and prostate tumors, targeting of androgen signaling has remained a mainstay for the treatment of aggressive prostate cancer. Over the years, multiple approaches have been evaluated to effectively target the androgen signaling pathway that include direct targeting of the androgens, androgen receptor (AR), AR co-regulators or other alternate mechanisms that impact the outcome of androgen signaling. -

Orteronel for Metastatic Hormone-Relapsed Prostate Cancer

Horizon Scanning Centre March 2013 Orteronel for metastatic hormone- relapsed prostate cancer following chemotherapy SUMMARY NIHR HSC ID: 4870 Orteronel is intended to be used as therapy for the treatment of hormone- relapsed prostate cancer following progression despite docetaxel-containing chemotherapy. If licensed, it will provide an additional treatment option for this patient group. Orteronel is a reversible, non-steroidal androgen biosynthesis inhibitor that selectively inhibits the 17,20 lyase enzyme, This briefing is suppressing the production of testosterone. based on information Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men in the UK, accounting for available at the time 25% of all male cancers. The main risk factor is increasing age, with an of research and a average of 75% of cases diagnosed in men aged 65 years and over. In 2010, limited literature there were 37,354 new diagnoses registered in England and Wales and in search. It is not 2011, there were 9,671 deaths. intended to be a definitive statement Current treatment options include hormonal therapies, (glucocorticoids, low- on the safety, dose oestrogens, selective 17,20 lyase inhibitors, or novel androgen receptor efficacy or antagonists), chemotherapies (docetaxel, mitoxantrone) and effectiveness of the immunotherapies (sipuleucel-T). Orteronel is currently in phase III clinical health technology trials comparing its effect on overall survival and event-free survival against covered and should treatment with placebo. These trials are expected to complete in 2013 and not be used for 2015. commercial purposes or commissioning without additional information. This briefing presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). -

Development of Combination Therapy for Prostate Cancer

DEVELOPMENT OF COMBINATION THERAPY FOR PROSTATE CANCER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Alexander R. Root July 2017 © 2017 Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DEVELOPMENT OF COMBINATION THERAPY FOR PROSTATE CANCER Alexander R. Root, Ph.D. Cornell University 2017 There is an unmet need in prostate cancer for effective therapies to prevent the emergence of resistance. Combinations of small molecules targeting key pathways are a promising strategy. I investigated how populations of the early metastatic prostate cancer cell line LNCaP respond at the proteomic and pheno- typic levels to six clinically-relevant, one-drug treatments and their 15 pairs of two-drug combinations, administered simultaneously to treatment-naive cells. After 24 hours of drug addition for all 21 drug treatments I measured 52 total- proteins by selected-reaction monitoring mass-spectrometry based proteomics (SRM), 20 phospho-proteins, and 50 total-proteins by reverse-phase protein ar- rays (RPPA). I measured phenotypic effects on cell proliferation and apoptosis in all conditions using phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy. Network analysis identified (phospho)-proteins with large responses to drug treatments that are druggable with FDA-approved drugs or have nearest-neighbors that are druggable. A total of ten drugs targeting these nearest responder (phospho)-proteins were tested in single, double, and triple combinations. I found that 7 out of 10 triple combinations co-targeting androgen receptor and PI3K pathways were no more effective than the two-drug combination at the doses tested: PRKC (en- zastaurin), MAPK (losmapimod), STAT3 (napabucasin), HDAC (panobinostat), SRC (saracatinib), casein kinase (silmitasertib), MAPK (ulixertinib). -

( 12 ) United States Patent

US010314797B2 (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 10 , 314 ,797 B2 Narayanan et al. ( 45 ) Date of Patent : * Jun . 11, 2019 ( 54 ) SELECTIVE ANDROGEN RECEPTOR ( 56 ) References Cited DEGRADER (SARD ) LIGANDS AND METHODS OF USE THEREOF U . S . PATENT DOCUMENTS 5 ,480 ,656 A 1 / 1996 Okada et al . (71 ) Applicant: University of Tennessee Research 5 ,575 , 987 A 11/ 1996 Kamei et al . Foundation , Knoxville , TN (US ) 5 ,631 , 020 A 5 / 1997 Okada et al. 5 , 643 ,607 A 7 / 1997 Okada et al. 5 ,716 ,640 A 2 / 1998 Kamei et al. ( 72 ) Inventors : Ramesh Narayanan , Cordova , TN 5 , 814 ,342 A 9 / 1998 Okada et al . (US ) ; Duane D . Miller , Collierville , 6 ,036 , 976 A 3 / 2000 Takechi et al . TN (US ) ; Thamarai Ponnusamy , 7 , 118 , 552 B2 10 / 2006 Shaw et al . Memphis , TN (US ); Dong - Jin Hwang, 7 , 220 , 247 B25 / 2007 Shaw et al . 7 ,500 , 964 B23 / 2009 Shaw et al . Arlington , TN (US ) ; Yali He, 9 ,815 , 776 B2 * 11 / 2017 Narayanan . .. .. C07C 255 /60 Germantown , TN (US ) 9 , 834 , 507 B2 * 12 / 2017 Narayanan . .. .. .. C07C 255 /60 2005 /0101657 A1 5 /2005 Furuya et al . (73 ) Assignee : University of Tennessee Research 2007 /0265290 A1 11/ 2007 Dalton et al . 2010 /0227846 AL 9 /2010 Ito et al. Foundation , Knoxville , TN ( US ) 2014 / 0018433 A11 / 2014 Dalton et al . ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer , the term of this 2018 /0118663 A1 * 5 / 2018 Narayanan . C07C 237/ 20 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS U . S . -

Download Product Insert (PDF)

PRODUCT INFORMATION Orteronel Item No. 24191 CAS Registry No.: 566939-85-3 Formal Name: 6-[(7S)-6,7-dihydro-7-hydroxy- 5H-pyrrolo[1,2-c]imidazol-7-yl]-N- O methyl-2-naphthalenecarboxamide Synonym: TAK-700 N MF: C H N O 18 17 3 2 H OH N FW: 307.3 Purity: ≥98% N UV/Vis.: λmax: 237, 280 nm Supplied as: A crystalline solid Storage: -20°C Stability: ≥2 years Information represents the product specifications. Batch specific analytical results are provided on each certificate of analysis. Laboratory Procedures Orteronel is supplied as a crystalline solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the orteronel in the solvent of choice. Orteronel is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol, DMSO, and dimethyl formamide (DMF), which should be purged with an inert gas. The solubility of orteronel in ethanol is approximately 0.2 mg/ml and approximately 10 mg/ml in DMSO and DMF. Description Orteronel is a non-steroidal inhibitor of the 17,20-lyase activity of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoform CYP17A1 (IC50s = 48 and 19 nM for the rat and human enzyme, respectively), which is the CYP17A1 activity that converts progestogens into androgens.1 Orteronel is selective for the 17,20-lyase activity of CYP17A1 over its 11-hydroxylase activity and CYP3A4 (IC50s = >1,000 and >10,000 nM, respectively). It decreases adrenocorticotropic hormone-induced production of DHEA, androstenedione, cortisol, and aldosterone in monkey adrenal cells (IC50s = 110, 130, 310, and 4,400 nmol/L, respectively) and inhibits DHEA production in NCI-H295R human adrenocortical tumor cells.2 A single oral dose of orteronel (0.3-10 mg/kg) dose-dependently decreases DHEA, cortisol, and testosterone levels in the plasma of intact cynomolgus monkeys for at least 10 hours, and chronic dosing of 15 mg/kg twice daily suppresses levels for up to seven days of treatment. -

HSD3B1 and Response to a Nonsteroidal CYP17A1 Inhibitor in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

Research JAMA Oncology | Brief Report HSD3B1 and Response to a Nonsteroidal CYP17A1 Inhibitor in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Nima Almassi, MD; Chad Reichard, MD; Jianbo Li, PhD; Carly Russell, MS; Jaselle Perry, MS; Charles J. Ryan, MD; Terence Friedlander, MD; Nima Sharifi, MD Invited Commentary page 562 IMPORTANCE The HSD3B1 (1245C) germline variant encodes for a gain-of-function missense Related article page 558 in 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoenzyme 1 (3βHSD1) that results in increased dihydrotestosterone synthesis from extragonadal precursors and is predictive of more rapid progression to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). OBJECTIVE To determine whether the HSD3B1 (1245C) genotype is predictive of clinical response to extragonadal androgen ablation with nonsteroidal 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase (CYP17A1) inhibition in men with metastatic CRPC. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS An observational study of men with metastatic CRPC treated with ketoconazole between June 1998 and December 2012 was conducted at the University of California, San Francisco. EXPOSURES Extragonadal androgen ablation with the nonsteroidal CYP17A1 inhibitor ketoconazole among men with metastatic CRPC. MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The primary end points of analysis were duration of ketoconazole therapy and time to disease progression stratified by HSD3B1 genotype. Disease progression was defined as either biochemical or radiographic progression, using the Prostate Cancer Working Group 3 and Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 definitions, respectively. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate time on therapy and time to disease progression. A log-rank test for trend was used to compare outcomes by HSD3B1 genotype. RESULTS A total of 90 men (median [interquartile range] age, 61.5 [55.3-67.0] years) with metastatic CRPC were included in the analysis, with sufficient data to determine duration of ketoconazole therapy and time to disease progression in 88 and 81 patients, respectively.