Kalmar Nyckel SAILS AGAIN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016 Welcome to the Junk Rig Glossary! The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) is a Member Project of the Junk Rig Association, initiated by Bruce Weller who, as a then new member, found that he needed a junk 'dictionary’. The aim is to create a comprehensive and fully inclusive glossary of all terms pertaining to junk rig, its implementation and characteristics. It is intended to benefit all who are interested in junk rig, its history and on-going development. A goal of the JRG Project is to encourage a standard vocabulary to assist clarity of expression and understanding. Thus, where competing terms are in common use, one has generally been selected as standard (please see Glossary Conventions: Standard Versus Non-Standard Terms, below) This is in no way intended to impugn non-standard terms or those who favour them. Standard usage is voluntary, and such designations are wide open to review and change. Where possible, terminology established by Hasler and McLeod in Practical Junk Rig has been preferred. Where innovators have developed a planform and associated rigging, their terminology for innovative features is preferred. Otherwise, standards are educed, insofar as possible, from common usage in other publications and online discussion. Your participation in JRG content is warmly welcomed. Comments, suggestions and/or corrections may be submitted to [email protected], or via related fora. Thank you for using this resource! The Editors: Dave Zeiger Bruce Weller Lesley Verbrugge Shemaya Laurel Contents Some sections are not yet completed. ∙ Common Terms ∙ Common Junk Rigs ∙ Handy references Common Acronyms Formulae and Ratios Fabric materials Rope materials ∙ ∙ Glossary Conventions Participation and Feedback Standard vs. -

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

ORC Rating Systems 2017 ORC International & ORC Club

World Leader in Rating Technology OFFSHORE RACING CONGRESS ORC Rating Systems 2017 ORC International & ORC Club Copyright © 2017 Offshore Racing Congress. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is only with the permission of the Offshore Racing Congress. Cover picture: ORC European Championship, Porto Carras, Greece 2016 by courtesy Fabio Taccola Margin bars denote rule changes from 2016 version Deleted rule from 2016 version: 205.3, 403.4 O R C World leader in Rating Technology ORC RATING SYSTEMS International ORC Club 2017 Offshore Racing Congress, Ltd. www.orc.org [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................... 4 1. LIMITS AND DEFAULTS 100 General ……………………….......................... 6 101 Materials …….................................................... 7 102 Crew Weight ...................................................... 7 103 Hull ….……....................................................... 7 104 Appendages …………....................................... 8 105 Propeller ……………........................................ 8 106 Stability ……..................................................... 8 107 Righting Moment …………………………….. 8 108 Rig …………………………………………… 10 109 Mainsail …………………………….…...….... 10 110 Mizzen ………………………...………...…... 11 111 Headsail ………………………..…………..… 11 112 Mizzen Staysail ……………………...………. 12 113 Symmetric Spinnaker ………………………... 12 G SYSTEMS 114 Asymmetric Spinnaker ………………...……. 12 2. RULES APPLYING WHILE RACING 200 Crew weight …………………………………. 14 RATIN ORC 201 Ballast, Fixtures -

Appropriate Sailing Rigs for Artisanal Fishing Craft in Developing Nations

SPC/Fisheries 16/Background Paper 1 2 July 1984 ORIGINAL : ENGLISH SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION SIXTEENTH REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING ON FISHERIES (Noumea, New Caledonia, 13-17 August 1984) APPROPRIATE SAILING RIGS FOR ARTISANAL FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING NATIONS by A.J. Akester Director MacAlister Elliott and Partners, Ltd., U.K. and J.F. Fyson Fishery Industry Officer (Vessels) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy LIBRARY SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION SPC/Fisheries 16/Background Paper 1 Page 1 APPROPRIATE SAILING RIGS FOR ARTISANAL FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING NATIONS A.J. Akester Director MacAlister Elliott and Partners, Ltd., U.K. and J.F. Fyson Fishery Industry Officer (Vessels) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy SYNOPSIS The plight of many subsistence and artisanal fisheries, caused by fuel costs and mechanisation problems, is described. The authors, through experience of practical sail development projects at beach level in developing nations, outline what can be achieved by the introduction of locally produced sailing rigs and discuss the choice and merits of some rig configurations. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. RISING FUEL COSTS AND THEIR EFFECT ON SMALL MECHANISED FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES 3. SOME SOLUTIONS TO THE PROBLEM 3.1 Improved engines and propelling devices 3.2 Rationalisation of Power Requirements According to Fishing Method 3.3 The Use of Sail 4. SAILING RIGS FOR SMALL FISHING CRAFT 4.1 Requirements of a Sailing Rig 4.2 Project Experience 5. DESCRIPTIONS OF RIGS USED IN DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 5.1 Gaff Rig 5.2 Sprit Rig 5.3 Lug Sails 5.3.1 Chinese type, fully battened lug sail 5.3.2 Dipping lug 5.3.3 Standing lug 5.4 Gunter Rig 5.5 Lateen Rig 6. -

Mast Furling Installation Guide

NORTH SAILS MAST FURLING INSTALLATION GUIDE Congratulations on purchasing your new North Mast Furling Mainsail. This guide is intended to help better understand the key construction elements, usage and installation of your sail. If you have any questions after reading this document and before installing your sail, please contact your North Sails representative. It is best to have two people installing the sail which can be accomplished in less than one hour. Your boat needs facing directly into the wind and ideally the wind speed should be less than 8 knots. Step 1 Unpack your Sail Begin by removing your North Sails Purchasers Pack including your Quality Control and Warranty information. Reserve for future reference. Locate and identify the battens (if any) and reserve for installation later. Step 2 Attach the Mainsail Tack Begin by unrolling your mainsail on the side deck from luff to leech. Lift the mainsail tack area and attach to your tack fitting. Your new Mast Furling mainsail incorporates a North Sails exclusive Rope Tack. This feature is designed to provide a soft and easily furled corner attachment. The sail has less patching the normal corner, but has the Spectra/Dyneema rope splayed and sewn into the sail to proved strength. Please ensure the tack rope is connected to a smooth hook or shackle to ensure durability and that no chafing occurs. NOTE: If your mainsail has a Crab Claw Cutaway and two webbing attachment points – Please read the Stowaway Mast Furling Mainsail installation guide. Step 2 www.northsails.com Step 3 Attach the Mainsail Clew Lift the mainsail clew to the end of the boom and run the outhaul line through the clew block. -

Website Address

website address: http://canusail.org/ S SU E 4 8 AMERICAN CaNOE ASSOCIATION MARCH 2016 NATIONAL SaILING COMMITTEE 2. CALENDAR 9. RACE RESULTS 4. FOR SALE 13. ANNOUNCEMENTS 5. HOKULE: AROUND THE WORLD IN A SAIL 14. ACA NSC COMMITTEE CANOE 6. TEN DAYS IN THE LIFE OF A SAILOR JOHN DEPA 16. SUGAR ISLAND CANOE SAILING 2016 SCHEDULE CRUISING CLASS aTLANTIC DIVISION ACA Camp, Lake Sebago, Sloatsburg, NY June 26, Sunday, “Free sail” 10 am-4 pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) Lady Bug Trophy –Divisional Cruising Class Championships Saturday, July 9 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 10 11 am ADK Trophy - Cruising Class - Two sailors to a boat Saturday, July 16 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 17 11 am “Free sail” /Workshop Saturday July 23 10am-4pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Learn the techniques of cruising class sailing, using a paddle instead of a rudder. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) . Sebago series race #1 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) July 30, Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #2 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. 6 Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #3 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. -

NX Wind PLUS

NX Wind PLUS - Instrument - Installation and Operation Manual English WIND English 1 English WIND 1 Part specification .............................................................................................. 3 2 Installation ......................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Installing the instrument ..................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Installing the instrument to the WSI-box ................................................... 7 2.1.2 Installing the instrument to the NX2 Server ............................................... 8 2.1.3 Connecting to another Nexus instrument. ................................................. 8 3 First start (only in a Nexus Network) ............................................................... 8 3.1 Initialising the instrument ................................................................................... 8 3.2 Re-initialising the instrument .............................................................................. 9 4 Operation ......................................................................................................... 10 4.1 How to use the push buttons ........................................................................... 10 4.1.1 Lighting ................................................................................................... 11 4.2 Main function .................................................................................................. -

December 2007 Crew Journal of the Barque James Craig

December 2007 Crew journal of the barque James Craig Full & By December 2007 Full & By The crew journal of the barque James Craig http://www.australianheritagefleet.com.au/JCraig/JCraig.html Compiled by Peter Davey [email protected] Production and photos by John Spiers All crew and others associated with the James Craig are very welcome to submit material. The opinions expressed in this journal may not necessarily be the viewpoint of the Sydney Maritime Museum, the Sydney Heritage Fleet or the crew of the James Craig or its officers. 2 December 2007 Full & By APEC parade of sail - Windeward Bound, New Endeavour, James Craig, Endeavour replica, One and All Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 7 Radio procedures on James Craig adio procedures being used onboard discomfort. Effective communication Rare from professional to appalling relies on message being concise and clear. - mostly on the appalling side. The radio Consider carefully what is to be said before intercoms are not mobile phones. beginning to transmit. Other operators may The ship, and the ship’s company are be waiting to use the network. judged by our appearance and our radio procedures. Remember you may have Some standard words and phases. to justify your transmission to a marine Affirm - Yes, or correct, or that is cor- court of inquiry. All radio transmissions rect. or I agree on VHF Port working frequencies are Negative - No, or this is incorrect or monitored and tape recorded by the Port Permission not granted. -

PDF Scan to USB Stick

REVIEWS Alf Åberg. FOLKET I NYA SVERIGE. VÅR KOLONI VID DELAWAREFLODEN 1638-1655. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur, 1987. 198 pp., illustrated. Voluminous and detailed as the scholarly literature about the seventeenth-century Swedish settlements on the Delaware River has been down through the centuries, Alf Åberg makes no claim of contributing anything essentially new to the subject of this modest volume. Rather his purpose has been to retell the story of this footnote to Swedish history for the modern layman who reads Swedish on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of the founding of New Sweden, Nova Sveda [Nya Sverige], 1638). As usual, Alf Åberg has succeeded remarkably well in fulfilling his purpose—so well, in fact, that a translation into American English of Folket i Nya Sverige can be recommended with enthusiasm. By soberly and sensibly confining himself to the facts as we presently are able to discern them, Alf Åberg draws repeated attention to two leitmotifs, so to speak, that resound throughout his chronological retelling of the story itself: the international coopera• tive—and competitive—effort that the enterprise essentially was and the penchant toward failure, rather than success, that typified it. To expand briefly on these themes, Swedish and Dutch capital was required to finance the initial voyage of the ships Kalmar Nyckel and Gripen in their pursuit of such viable commodities as tobacco and furs; and since the Dutch then had far greater expertise at seafaring than did the Swedes, the leadership and most of the sailors for these vessels were recruited in Amsterdam rather than the fledgling seaport of Göteborg. -

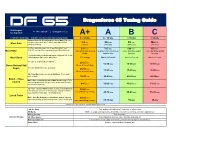

Sail Tuning Guide LINK

DF 65 Dragonforce 65 Tuning Guide Phil Burgess M - 0413 200 608 E - [email protected] 1st July 2020 A+ A B C Estimated wind range - depends on wave action and tacking ability 0 - 10 kts 8 - 15 kts > 15 kts > 20 kts Distance from Jib Pivot Eyelet to front of Mast (Can also use gate control as a ram to induce mast bend without line 4th Line Line Aft Mast Gate 3rd 5th Max changing forestay). (175 mm) (176 mm) (177 mm) (178 mm) A+ From backstay crane hole to top of backstay hook 951 mm. 785 mm. 698 mm. 620 mm. A, B, C From top of Forestay tang to top of backstay hook. Mast Rake From soft to firm as wind Slightly firmer backstay & Firmer backstay & tight Firmer backstay & tight builds tight forestay forestay forestay Tension Backstay so Mast bend matches Mainsail luff, so sail Mast Bend easily flops from side to side when tilted Soft settings Match luff round Match luff round Match luff round At centre of Jib Boom deepest point 20-25 mm, 15-20 mm 15-20 mm 10-15 mm Boom Outhaul Sail 15 mm at top of range At centre of Main Boom deepest point Depth 25-30 mm, 15-25 mm 15-20 mm 10-20 mm 15 mm at top of range Jib - from Mast centre to end of Jib Boom. Place small mark on deck 38-43 mm 40-45mm 40-45mm 40-45mm Boom - Close Main - from centreline at end of Main Boom. (Adjust Tx for hauled exponential adjustment for last 20 mm sheet travel for high and low pointing mode) 8-15 mm 10-20 mm 15-25 mm 15-25 mm Jib - from Centre of Mast to leech at mid point of jib leech. -

Kalmar Nyckel: Using a 17Th Century Dutch Pinnace to Teach Physics and More DTI 2016-2017 Ancient Inventions

Kalmar Nyckel: Using a 17th century Dutch Pinnace to Teach Physics and More DTI 2016-2017 Ancient Inventions Terri Eros Challenges H.B. duPont Middle School, while located in a very suburban setting, serves a very diverse population. There are approximately 900 students in grades 6-8, with students almost evenly split between urban and suburban backgrounds. The academic readiness also varies greatly with relation to reading and math skills. It is not unusual to have a range of students reading all the way from a pre-primer level to those comfortable with high school text. In some cases the disparity is due to limited English proficiency. The math skills are similarly distributed with some students needing calculators for 2-digit addition while others are comfortable solving algebraic equations. To better meet student needs, our school piloted having honors classes in Science and Social Studies last year. Groupings were based on reading level for Social Studies and Math level for Science. The outcome was less than ideal for Science. At the middle school level, language skills are more important so that is now the basis of grouping for the 2016-2017 school year. In addition, our school is aiming for full inclusion. Students include those that have severe physical and/or emotional needs that interfere with their ability to interact linguistically, through either speech or writing. Despite these limitations, there is still an interest and an expectation to succeed in the Science classroom. The challenge is to incorporate the rigor of the Next Generation Science Standards, with its emphasis on student driven learning, while finding multiple access points for the students based on readiness. -

BILGE PUMPING ARRANGEMENTS MSIS27 CHAPTER 5 Rev 09.21

INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE GUIDANCE OF SURVEYORS ON BILGE PUMPING ARRANGEMENTS MSIS27 CHAPTER 5 Rev 09.21 Instructions to Surveyors – Fishing Vessels Bilge Pumping Document Amendment History PREFACE 0.1 These Marine Survey Instructions for the Guidance of Surveyors (MSIS) are not legal requirements in themselves. They may refer to statutory requirements elsewhere. They do represent the MCA policy for MCA surveyors to follow. 0.2 If for reasons of practicality, for instance, these cannot be followed then the surveyor must seek at least an equivalent arrangement, based on information from the owner/operator. Whenever possible guidance should be sought from either Principal Consultant Surveyors or Survey Operation Branch, in order to maintain consistency between Marine Offices. UK Maritime Services/Technical Services Ship Standards Bay2/22 Spring Place 105 Commercial Road Southampton SO15 1EG MSIS 27.5 R09.21/Page 2 of 16 Instructions to Surveyors – Fishing Vessels Bilge Pumping Document Amendment History RECENT AMENDMENTS The amendments made in the most recent publication are shown below, amendments made in previous publications are shown in the document Amendment History. Version Status / Change Date Author Content Next Review Number Reviewer Approver Date/Expiry Date 10.20 • Add requirement that 20/10/20 D Fenner G Stone 20/10/22 bilge sensors in compartments containing pollutants shall not automatically start bilge pumps • Requirements for supply of powered bilge starting arrangements through separate switchboard updated. • Main watertight compartment is defined 09.21 • Amendments to reflect 31/8/2021 D Fenner G Stone 31/8/23 publication of MSN1871 Amendment No.2 MSIS 27.5 R09.21/Page 3 of 16 Instructions to Surveyors – Fishing Vessels Bilge Pumping Document Amendment History PREFACE .......................................................................................................