An Archive of Settler Belonging: Local Feeling, Land, and the Forest Resource on Vancouver Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Nations Nutrition and Health Conference

First Nations Nutrition and Health Conference Proceedings Alfred Wong, Editor June 19 - 20, 2003 Recreation Centre, 100 Lower Capilano Road, Squamish Nation Sponsored by Friends of Aboriginal Health 2 Notice The Friends of Aboriginal Health through a copyright agreement with Arbokem Inc. permits the unlimited use of the content of the proceedings of the First Nations Nutrition and Health Conference, for the non-commercial promotion of health and wellness among the people of the First Nations. ISBN: 0-929020-02-3 © Arbokem Inc., Vancouver, Canada, 2003-2004 www.aboriginalhealth.net Printed in Canada AK25818W2 Proceedings of the First Nations Nutrition and Health Conference, 2003 3 Table of Content Page Notice 2 Table of Content 3 Foreword 5 Conference Program 6 Time for justice, sovereignty and health after more than 200 years of foreign 8 colonization and cultural destruction. Ovide Mercredi The Present Status of Aboriginal Health in British Columbia. Lydia Hwitsum 9 Health of the people and community. Gerald Amos 16 Loss of Use of a Traditional Fishery – The Kitamaat Eulachon. Michael Gordon 17 Wellness Governing Mode: The Union of Our Two Worlds and Traditional 18 Knowledge. Andy Carvill and David Anthony Ravensdale Environmental Impact on Food and Lifestyle. :Wik Tna A Seq Nakoo (Ida John) 19 “Our Food is Our Medicine”: Traditional Plant Foods, Traditional Ecological 22 Knowledge and Health in a Changing Environment. Nancy J. Turner and Rosemary Ommer Acculturation and natural food sources of a coastal community. Wata (Christine 40 Joseph) Impact of Fish Farming on the Natural Food Resources of 41 First Nations People. Sergio Paone Overall Health - Mental, Emotional, Spiritual and Physical Aspects. -

Songhees Pictorial

Songhees Pictorial A History ofthe Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790 - 1912 by Grant Keddie Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, 2003. 175pp., illus., maps, bib., index. $39.95. ISBN 0-7726-4964-2. I remember making an appointment with Dan Savard in or der to view the Sali sh division ofthe provincial museum's photo collections. After some security precautions, I was ushered into a vast room ofcabi nets in which were the ethnological photographs. One corner was the Salish division- fairly small compared with the larger room and yet what a goldmine of images. [ spent my day thumbing through pictures and writing down the numbers name Songhees appeared. Given the similarity of the sounds of of cool photos I wished to purchase. It didn't take too long to some of these names to Sami sh and Saanich, l would be more cau see that I could never personally afford even the numbers I had tious as to whom is being referred. The oldest journal reference written down at that point. [ was struck by the number of quite indicating tribal territory in this area is the Galiano expedi tion excellent photos in the collection, which had not been published (Wagner 1933). From June 5th to June 9th 1792, contact was to my knowledge. I compared this with the few photos that seem maintained with Tetacus, a Makah tyee who accompanied the to be published again and again. Well, Grant Keddie has had expedi tion to his "seed gathering" village at Esquimalt Harbour. access to this intriguing collection, with modern high-resolution At this time, Victoria may have been in Makah territory or at least scanning equipment, and has prepared this edited collecti on fo r high-ranking marriage alliances gave them access to the camus our v1ewmg. -

A Study of the Wellington Miners5 Strike of 1890-911 JEREMY MOUAT

The Politics of Goal: A Study of the Wellington Miners5 Strike of 1890-911 JEREMY MOUAT The coal miners of Vancouver Island occupy a special place in the history of British Columbia. The communities in which they and their families lived — Ladysmith, Wellington, Nanaimo, and Cumberland — experi enced class tensions to a degree and duration rarely seen in other parts of the province. An Island miner involved in the 1912 strike, for example, might have had a grandparent who went through the 1877 strike or a parent who witnessed the 1890 strike. These outbursts of militancy reflect the uneasiness in the social relations of production on the coal fields. Class tensions found expression in other ways as well, such as the ethnic preju dice of the miners or their left-leaning political representatives. Each strike was fought out in a different context, informed both by past struggles and current conditions. What follows is an attempt to explore the context of one such episode, the Wellington strike of 1890-91. It began quietly enough on a Monday morning, 19 May 1890, when miners employed at the Dunsmuirs' Wellington colliery on Vancouver Island arrived late for work. The action expressed their demand for an eight-hour working day and recognition of their union. The Dunsmuirs refused to grant either of these, and an eighteen-month struggle followed. When the strike was finally called off in November 1891, the Wellington miners had failed to achieve their two goals. The strike has received scant attention from historians, a neglect it scarcely deserves.2 At a time when the industry played a vital role in the 1 I would like to thank R. -

Camosun College Transportation and Parking Management Plan

Camosun College Transportation and Parking Management Plan By Todd Litman Victoria Transport Policy Institute 2009 Revised June, 2009 Camosun College Transportation and Parking Management Plan Victoria Transport Policy Institute Camosun College Transportation and Parking Management Plan 18 June 2009 By Todd Litman Victoria Transport Policy Institute Summary The Camosun College Transportation and Parking Management (TPM) Project includes a planning process to identify optimal solutions to campus transportation and parking problems. Through the TPM project, specific ways to improve transportation and parking management in order to create a more sustainable campus will be identified. The plan will be flexible and responsive to future demands and conditions. This TPM plan describes existing transportation and parking conditions, identifies current and future challenges, and recommends specific transportation and parking policies and management programs. The TPM Project will continue beyond this plan through the implementation phases. 2 Camosun College Transportation and Parking Management Plan Victoria Transport Policy Institute Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Planning Goals and Objectives ....................................................................................................................... 5 Camosun College Campuses .......................................................................................................................... -

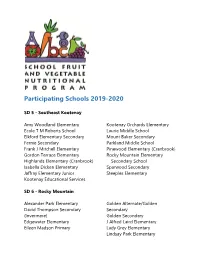

Participating Schools 2019-2020

Participating Schools 2019-2020 SD 5 - Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland Elementary Kootenay Orchards Elementary Ecole T M Roberts School Laurie Middle School Elkford Elementary Secondary Mount Baker Secondary Fernie Secondary Parkland Middle School Frank J Mitchell Elementary Pinewood Elementary (Cranbrook) Gordon Terrace Elementary Rocky Mountain Elementary Highlands Elementary (Cranbrook) Secondary School Isabella Dicken Elementary Sparwood Secondary Jaffray Elementary Junior Steeples Elementary Kootenay Educational Services SD 6 - Rocky Mountain Alexander Park Elementary Golden Alternate/Golden David Thompson Secondary Secondary (Invermere) Golden Secondary Edgewater Elementary J Alfred Laird Elementary Eileen Madson Primary Lady Grey Elementary Lindsay Park Elementary Martin Morigeau Elementary Open Doors Alternate Education Marysville Elementary Selkirk Secondary McKim Middle School Windermere Elementary Nicholson Elementary SD 8 - Kootenay Lake Adam Robertson Elementary Mount Sentinel Secondary Blewett Elementary School Prince Charles Brent Kennedy Elementary Secondary/Wildflower Program Canyon-Lister Elementary Redfish Elementary School Crawford Bay Elem-Secondary Rosemont Elementary Creston Homelinks/Strong Start Salmo Elementary Erickson Elementary Salmo Secondary Hume Elementary School South Nelson Elementary J V Humphries Trafalgar Middle School Elementary/Secondary W E Graham Community School Jewett Elementary Wildflower School L V Rogers Secondary Winlaw Elementary School SD 10 - Arrow Lakes Burton Elementary School Edgewood -

Cowichan Valley Trail Brochure (2021)

FLIP FOR MAP FOR FLIP treaded tires are highly recommended. recommended. highly are tires treaded Kinsol Trestle. Surface conditions vary so cyclists should note that that note should cyclists so vary conditions Surface Trestle. Kinsol reconnects with your start point in Duncan. Duncan. in point start your with reconnects south through forests and rural farmland before arriving at the Historic Historic the at arriving before farmland rural and forests through south Ganges. Catch another ferry from Vesuvius to Crofton and a short ride ride short a and Crofton to Vesuvius from ferry another Catch Ganges. Glenora Trails Head Park on Robertson Road. The trail route travels travels route trail The Road. Robertson on Park Head Trails Glenora from Swartz Bay, the route meanders along roads to the village of of village the to roads along meanders route the Bay, Swartz from This popular cycling and equestrian route starts and finishes at at finishes and starts route equestrian and cycling popular This Difficulty: Difficulty: Saanich Peninsula. After a quick ferry connection to Saltspring Island Island Saltspring to connection ferry quick a After Peninsula. Saanich Easy Distance: Distance: before connecting with the Lochside Trail and heading north up the the up north heading and Trail Lochside the with connecting before 26 km return km 26 ROUTE B — Glenora Trails Head Park to Kinsol Trestle Kinsol to Park Head Trails Glenora — B ROUTE route continues on the Galloping Goose Regional Trail into Victoria Victoria into Trail Regional Goose Galloping the on continues route dropping into Langford, along the Sooke Hills Wilderness Trail. The The Trail. -

Craigdarroch Military Hospital: a Canadian War Story

Craigdarroch Military Hospital: A Canadian War Story Bruce Davies Curator © Craigdarroch Castle 2016 2 Abstract As one of many military hospitals operated by the federal government during and after The Great War of 1914-1918, the Dunsmuir house “Craigdarroch” is today a lens through which museum staff and visitors can learn how Canada cared for its injured and disabled veterans. Broad examination of military and civilian medical services overseas, across Canada, and in particular, at Craigdarroch, shows that the Castle and the Dunsmuir family played a significant role in a crucial period of Canada’s history. This paper describes the medical care that wounded and sick Canadian soldiers encountered in France, Belgium, Britain, and Canada. It explains some of the measures taken to help permanently disabled veterans successfully return to civilian life. Also covered are the comprehensive building renovations made to Craigdarroch, the hospital's official opening by HRH The Prince of Wales, and the question of why the hospital operated so briefly. By highlighting the wartime experiences of one Craigdarroch nurse and one Craigdarroch patient, it is seen that opportunities abound for rich story- telling in a new gallery now being planned for the museum. The paper includes an appendix offering a synopsis of the Dunsmuir family’s contributions to the War. 3 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................. 04 I. Canadian Medical Services -

Amends Letters Patent of Improvement Districts

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ORDER OF THE MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS AND HOUSING Local Government Act Ministerial Order No. M336 WHEREAS pursuant to the Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, B.C. Reg 30/2010 the Local Government Act (the ‘Act’), the minister is authorized to make orders amending the Letters Patent of an improvement district; AND WHEREAS s. 690 (1) of the Act requires that an improvement district must call an annual general meeting at least once in every 12 months; AND WHEREAS the Letters Patent for the improvement districts identified in Schedule 1 further restrict when an improvement district must hold their annual general meetings; AND WHEREAS the Letters Patent for the improvement districts identified in Schedule 1 require that elections for board of trustee positions (the “elections”) must only be held at the improvement district’s annual general meeting; AND WHEREAS the timeframe to hold annual general meetings limits an improvement district ability to delay an election, when necessary; AND WHEREAS the ability of an improvement district to hold an election separately from their annual general meeting increases accessibility for eligible electors; ~ J September 11, 2020 __________________________ ____________________________________________ Date Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing (This part is for administrative purposes only and is not part of the Order.) Authority under which Order is made: Act and section: Local Government Act, section 679 _____ __ Other: Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, OIC 50/2010_ Page 1 of 7 AND WHEREAS, I, Selina Robinson, Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, believe that improvement districts require the flexibility to hold elections and annual general meetings separately and without the additional timing restrictions currently established by their Letters Patent; NOW THEREFORE I HEREBY ORDER, pursuant to section 679 of the Act and the Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, B.C. -

The Influence of Political Leaders on the Provincial Performance of the Liberal Party in British Columbia

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1977 The Influence of oliticalP Leaders on the Provincial Performance of the Liberal Party in British Columbia Henrik J. von Winthus Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation von Winthus, Henrik J., "The Influence of oliticalP Leaders on the Provincial Performance of the Liberal Party in British Columbia" (1977). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1432. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1432 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF POLITICAL LEADERS ON THE PROVINCIAL PERFORMANCE OF THE LIBERAL PARTY IN BRITISH COLUMBIA By Henrik J. von Winthus ABSTRACT This thesis examines the development of Liberalism In British Columbia from the aspect of leader influence. It intends to verify the hypothesis that in the formative period of provincial politics in British Columbia (1871-1941) the average voter was more leader- oriented than party-oriented. The method of inquiry is predominantly historical. In chronological sequence the body of the thesis describes British Columbia's political history from 1871, when the province entered Canadian confederation, to the resignation of premier Thomas Dufferin Pattullo, in 1941. The incision was made at this point, because the following eleven year coalition period would not yield data relevant to the hypothesis. Implicitly, the performance of political leaders has also been evaluated in the light of Aristotelian expectations of the 'zoon politikon'. -

PROVINCI L Li L MUSEUM

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA REPORT OF THE PROVINCI_l_Li_L MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY • FOR THE YEAR 1930 PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C. : Printed by CHARLES F. BANFIELD, Printer to tbe King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1931. \ . To His Honour JAMES ALEXANDER MACDONALD, Administrator of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: The undersigned respectfully submits herewith the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History for the year 1930. SAMUEL LYNESS HOWE, Pt·ovincial Secretary. Pt·ovincial Secretary's Office, Victoria, B.O., March 26th, 1931. PROVINCIAl. MUSEUM OF NATURAl. HISTORY, VICTORIA, B.C., March 26th, 1931. The Ho1Wm·able S. L. Ho11ie, ProvinciaZ Secreta11}, Victo1·ia, B.a. Sm,-I have the honour, as Director of the Provincial Museum of Natural History, to lay before you the Report for the year ended December 31st, 1930, covering the activities of the Museum. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, FRANCIS KERMODE, Director. TABLE OF CONTENTS . PAGE. Staff of the Museum ............................. ------------ --- ------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- -------------- 6 Object.. .......... ------------------------------------------------ ----------------------------------------- -- ---------- -- ------------------------ ----- ------------------- 7 Admission .... ------------------------------------------------------ ------------------ -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

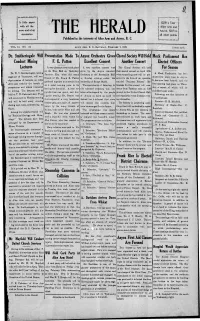

Dr. Smitheringale Will Conduct Mining Lectures

II } <-•• t-». •+—+.».+•«•+•»-•-••( " V*- f'.- T— A little paper $2.50 a Year j with all the Alice Arm and j news and a big Anyox. $2.75 to j circulation THE HERALD all other points, j Published in the interests of Alice Arm and Anyox, B. C. <»W»"»».».i«n«..»,» ••-• *-• •«** f VOL. 10, NO. 34 ALICE ARM, B. O, SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 1931 5 cents each. Dr. Smitheringale Will Presentation Made To Anyox Orchestra Gives Choral Society Will Hold Mock Parliament Has Conduct Mining F. E. Patton Excellent Concert Another Concert Elected Officers Lectures A very pleasant event took place A very excellent concert was The Choral Society will hold For Season at the Mine Hall on Saturday, given by the Anyox Amateur their second concert on April 16th Dr. W. V. Smitheringale, mining January 31st. when the many Orchestra at the Recreation Hall when something new will be pre A Mock Parliament has been engineer of Vancouver, will oon- friends of Mr. Frank E. Patton on Sunday evening under the sented in the form of an operetta, mooted for some time in Anyox. duot a series of lectures at Alice gathered together to entertain him leadership of Stuart Steele. entitled "Penitent Pirates." Re It has now been formed, and the -Arm next week for the benefit of first meeting took place on Thurs at a sooial evening prior to his The opportunity of listening to hearsals for this concert will com prospeotors and others interested day, a report of which will be leaving for the south. A very en this talented orchestra was not mence from Tuesday next at 7.30 in mining. -

Kinsol Trestle Rehabilitation CAPITAL CAMPAIGN

Kinsol Trestle Rehabilitation CAPITAL CAMPAIGN COWICHAN VALLEY, BRITISH COLUMBIA Save the Magnificent, Historic Kinsol Trestle By Jack Peake, Chair, Kinsol Trestle Capital Campaign hen I was asked to Chair the Cowichan Foundation Construction of the Kinsol Trestle campaign to raise $2 million to save the spectacular started in 1911 when forestry had W gained some ground on Vancouver Kinsol Trestle, I replied with an unhesitating, resounding YES. Island and a more efficient way to transport the region’s huge, old- There are so many compelling reasons why saving the Trestle growth timber was needed. The Trestle makes sense. I have made my gift to support rehabilitation of the was completed by Canadian National Trestle. I hope, after reading this information, you will join me Railways in 1920 as part of the and do the same. “Galloping Goose” rail line. Designed by engineers but built by local farmers and loggers, the History and Beauty Worth Saving Kinsol Trestle is one of the tallest There aren’t many opportunities Too many times, unfortunately, we free-standing and most spectacular in a lifetime to make a difference witness the disappearance of our timber rail trestle structures in the for generations to come. Saving heritage and wish we had done more world. At 614 feet in length and the Trestle for its rich history is a to preserve it. This is our chance to standing 145 feet above the salmon powerful reason to support this avoid such a loss for our community. bearing Koksilah River, the campaign. I imagine school children Saving the Trestle means we will keep Kinsol is an incredible structure walking across the Trestle in the years that window into a bygone era open worth preserving.