CD-1107 Transcription Address, “The Jewish-Christian Encounter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Jewish University 2021-2022 Academic Catalog

American Jewish University 2021-2022 Academic Catalog Table of Contents About AJU .........................................................................................................................................6 History of American Jewish University ..................................................................................................... 7 Mission Statement .................................................................................................................................... 8 Institutional Learning Outcomes............................................................................................................... 8 Who We Are .............................................................................................................................................. 8 Diversity Statement .................................................................................................................................. 9 Accreditation ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Accuracy of Information ........................................................................................................................... 9 Questions and Complaints ........................................................................................................................ 9 Contact American Jewish University ...................................................................................................... -

April/May/June 2014 Bulletin

1625 Ocean Avenue EAST MIDWOOD Brooklyn, NY 11230 718.338.3800 JEWISH CENTER www.emjc.org BULLETIN VOLUME LXXIV, Issue 4 THEY SHALL BUILD ME A SANCTUARY April/May/June 2014 AND Nisan/Iyar/Sivan/Tamuz 5774 I SHALL DWELL AMOUNG THEM A Message from our President… Randy Grossman We all, at times, reflect on the path that we are choosing in our lives and the experiences and events that come along to change our lives. A year ago, the idea of my being a co-president of a synagogue was unimaginable. With massive changes taking place in the medical care industry where I work, my parents' estate to settle 700 miles away, and my son's pending Bar Mitzvah, as well as the other routine activities that go along with having two school age children and a working spouse, the thought would never have entered my mind. With that said, I was honored and I am still excited about being co-president of the East Midwood Jewish Center with Toby Sanchez. We look forward to the challenges, which lay ahead, and to working with our staff, the Board of Trustees, and our generous congregation to meet those challenges. Our goals are to make EMJC more sustainable and to work always for the best interests of EMJC's future. My first away from EMJC official function was to attend the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) Centennial, "The Conversation of the Century." It was here where I learned that the movement would prefer for us to now refer to our Synagogue as a “Kehilla.” What is a Kehilla? Defined most simply, a Kehilla is a community, a group of people who have come together with shared purpose and in fellowship. -

Chanting Psalm 118:1-4 in Hallel Aaron Alexander, Elliot N

Chanting Psalm 118:1-4 in Hallel Aaron Alexander, Elliot N. Dorff, Reuven Hammer May, 2015 This teshuvah was approved on May 12, 2015 by a vote of twelve in favor, five against, and one abstention (12-5-1). Voting in Favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Joshua Heller, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Micah Peltz, Elie Spitz, Jay Stein. Voting Against: Rabbis Baruch Frydman-Kohl, David Hoffman, Adam Kligfeld, Paul Plotkin, Avram Reisner. Abstaining: Rabbi Daniel Nevins. Question: In chanting Psalm 118:1-4 in Hallel, should the congregation be instructed to repeat each line after the leader, or should the congregation be taught to repeat the first line after each of the first four? Answer: As we shall demonstrate below, Jewish tradition allows both practices and provides legal reasoning for both, ultimately leaving it to local custom to determine which to use. As indicated by the prayer books published by the Conservative Movement, however, the Conservative practice has been to follow the former custom, according to which the members of the congregation repeat each of the first four lines of Psalm 118 antiphonally after the leader, and our prayer books should continue to do so by printing the psalm as it is in the Psalter without any intervening lines. However, because the other custom exists and is acceptable, it should be mentioned as a possible way of chanting these verses of Hallel in the instructions. A. The Authority of Custom on this Matter What is clear from the earliest Rabbinic sources is that local customs varied as to how to recite Hallel, and each community was authorized to follow its own custom. -

The Early Years, 1947-1952 Office When That Camp Opened in 1950

numerous headings in various places. I suspect that materials on Ramah were not carefully preserved at the Seminary until the camps became a national concern. Since the early camps were local ventures, records were kept in the local offices. Yet, here, too, there were problems, particularly with regard to Camp Ramah in Maine, which was open for only two Camp Ramah: seasons (1948-49), then closed permanently; many of its records have disappeared. Some were transferred to the Camp Ramah in the Poconos The Early Years, 1947-1952 office when that camp opened in 1950. That office moved from Phila delphia to New York and then back to Philadelphia, and many of the Shuly Rubin Schwartz Maine records were probably lost or discarded at that time. Another valuable source of written information is the personal collections of yearbooks, educational outlines, and camp rosters saved by staff and campers. Needless to say, then, the selective nature of the preserved materials required much oral research. The number of people involved in. R.amah Introduction even during its early years is so large that I was forced to limit my A new chapter in the history of the Conservative movement began in 1947 interviewing to specific figures-directors, division heads, local rabbis, lay with the founding of Camp Ramah. Located in Conover, Wisconsin, people, and Seminary representatives-as opposed to choosing general Ramah was operated by the Chicago Council of Conservative Synagogues, staff and campers. the Midwest Branch of the United Synagogue, in cooperation with the In conducting research, an attempt was made to avoid the major pitfall Teachers Institute of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. -

124900176.Pdf

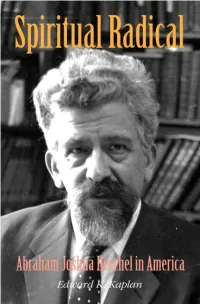

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

Walking with God Final:Cover 5/25/07 5:30 PM Page 1

4012-ZIG-Walking with God Final:Cover 5/25/07 5:30 PM Page 1 The Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies Walking with God Edited By Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson and Deborah Silver ogb hfrs vhfrs 4012-ZIG-Walking with God Final:Cover 5/25/07 5:30 PM Page 2 In Memory of Louise Held The Held Foundation Harold Held Joseph Held Robert Held Melissa Bordy Published in partnership with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism and the Rabbinical Assembly 4012-ZIG-Walking with God Final:4012-ZIG-Walking with God 5/25/07 4:18 PM Page 1 RABBI BRADLEY SHAVIT ARTSON DEAN AND VICE PRESIDENT IN THE GLORY DAYS OF THE MIDDLE AGES, TWO TITANS OF JEWISH THOUGHT, Rabbi Moses Maimonides (the Rambam) and Rabbi Moses Nachmanides (the Ramban) sparred. Their argument: was the obligation to believe in God one of the 613 commandments of the Torah, or was it the ground on which all the 613 commandments stood? Neither disputed that Jewish life flows from the fountain of faith, that connecting to God is a life-long journey for the seeking Jew and a pillar of Jewish life and religion. Not only the Middle Ages, but the modern age affirms that same conviction. Conservative Judaism, in Emet Ve-Emunah: Statement of Principles of Conservative Judaism, affirms, “We believe in God. Indeed, Judaism cannot be detached from belief in, or beliefs about God. … God is the principal figure in the story of the Jews and Judaism.” In the brochure, Conservative Judaism: Covenant and Commitment, the Rabbinical Assembly affirms, “God and the Jewish People share a bond of love and sacred responsibility, which expresses itself in our biblical brit (covenant).” It is to aid the contemporary Jew in the duty and privilege of exploring that relationship, of enlisting the rich resources of Judaism’s great sages through the ages, that the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies at the American Jewish University, in partnership with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism and the Rabbinical Assembly, has compiled and published this adult education course focused on Jewish apprehensions of God. -

THE FUTURE of the JEWISH COMMUNITY in AMERICA.Pdf

THE FUTURE OF THE «TASK FORCE REPORT THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE TASK FORCE ON THE FUTURE OF THE JEWISH COMMUNITY IN AMERICA MEMBERS LOUIS STERN, Chairman - Former President of the RABBI MARTIN S. ROZENBERG - The Com• Jewish Welfare Board and the Council of Jewish munity Synagogue, Sands Point, New York Federations and Welfare Funds MARSHALL SKLARE - Professor of American DAVID SI DORSKY, Consultant - Professor of Jewish Studies, Brandeis University Philosophy, Columbia University JOHN SLAWSON - Executive Vice President *RABBI JACOB B. AGUS - Congregation Beth El, Emeritus, American Jewish Committee Baltimore JAMES SLEEPER - Cambridge, Massachusetts ROBERT ALTER - Professor of Comparative Litera• SANFORD SOLENDER - Executive Vice President, ture, University of California at Berkeley Federation of Jewish Philanthropies of New York SHRAGA ARIAN - Superintendent, Board of Jewish City Education, Chicago HARRY STARR - President, Lucius N. Littauer WILLIAM AVRUNIN - Executive Vice President, Foundation Jewish Welfare Federation of Detroit ISAAC TOUBIN - Executive Vice President, Ameri• MAX W. BAY, M.D. - Co-Chairman of the Western can Association for Jewish Education Regional Council of the American Jewish SIDNEY Z. VINCENT - Executive Director, Jewish Committee Community Federation of Cleveland PHILIP BERNSTEIN - Executive Vice President, MAYNARD I. WISHNER - Chairman, Jewish Council of Jewish Federations and Welfare Funds Communal Affairs Commission of the American LUCY S. DAWIDOWICZ-Associate Professor of Jewish Committee Social History, Yeshiva University JOSEF HAYIM YERUSHALMI - Professor of RABBI IRA EISENSTEIN - President of the Recon• Jewish History, Harvard University struction's! Rabbinical College GEORGE M. ZELTZER - Detroit DANIEL J. ELAZAR - Director of the Center for LOUIS I. ZORENSKY - President of the Jewish the Study of Federalism, Temple University Federation of St. -

Shir Notes the Official Newsletter of Congregation Shir Ami Volume 14, Number 7, August-September 2016

Shir Notes The Official Newsletter of Congregation Shir Ami Volume 14, Number 7, August-September 2016. Affiliated with United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism Rabbi’s Column . Events of the Month Editor’s note: Rabbi Vorspan is on vacation and wasn’t able to submit his monthly column. Below is his column from Shabbat in the Park August 2011, as relevant as ever. Friday, August 26, 5:00 pm I was on my way to Dodger Stadium for "Jew Day" a at Warner Center Park couple of weeks ago when I passed a few of those guys standing on the The Jewish Federation and corner with signs that said, "Need to buy tickets." We all know this to be Shalom Institute sponsor this wording designed to keep them within the law, yet notifying passing Dodger annual Valley Shabbat in the Park fans (if they're in on the deception) of scalped ticket availability. with several Valley congregations, including Shir Ami. See flyer. And I got to thinking of how many other times we use words that we know really mean the opposite. We can call the 13th floor of a building the 14th BBQ and Barchu floor, but it's still the 13th floor. But superstitious people are appeased. Friday, September 9, 6:00 pm at Temple Ramat Zion An expression starting to get overworn is "Shut up," which, in current parlance, means we really want them to keep talking. When we nullify a Our annual BBQ dinner will be marriage, we are essentially saying the marriage never happened. Try prepared by Ventura Kosher, telling that to the guests who witnessed something going on a few years ago followed by White Shabbat Service which looked suspiciously like a wedding! Under the Stars. -

At Sinai God Proclaimed His Everlasting

At Sinai God proclaimed His everlasting relationship to the Jewish people when He uttered the awesome words, “I am the Lord your God.” The divine spark was at that moment implanted in every Jewish soul and became part of our essential being. t I is that spark that stirs us to seek our Maker and empowers us to overcome the conflicts between con- COMING HOME temporary cultural values and those of Judaism. At Sinai God also admonished our People not “to possess other gods in My rPesence.” The Emancipation which began in the late 18th century offered “other gods,” and too many Jews rejected Judaism for the glitter of secular gods. The early Reform movement sought to institutionalize that rejec- tion and developed an antipathy to the fundamentals of the faith. In our own day, there is renewed interest in ritual within the Reform movement and an increased emphasis on Jewish education in Conservative circles. Despite these trends, however, there is a growing sense of the inadequacy of the Reform and Conservative lifestyles among their members. The creation of patri- lineal descent as a criterion of Jewish identity by the Reform movement, in complete violation of Jewish law, is one of the greatest tragedies of Jewish history and has delivered an incalculable blow to the unity of our People. The American Jewish community is at a critical juncture. It is time to return to our roots; to the source of our being as a People; to Sinai and to ourT orah. It is time to come home. The first-person stories in this special section ewr e written by our brothers and sisters who have had to tr a v el long and arduous roads to attain the faith of our fathers and mothers. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS February 13, 1979 MAN, Ms

2558 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS February 13, 1979 MAN, Ms. HOLTZMAN, Mr. PEPPElt, Mr. GEP of Missouri, Mr. RICHMOND, Mr. BONIOR O! DONNELLY, Mr. DoRNAN, Mr. DOUGHERTY, Mr. HARDT, Mr. HOWARD , Mr. STARK , Mr. DORNAN , Michigan, Mr. BURGENER , Mr. LEHMAN, Mr. GOLDWATER, Mr. GRISHAM, Mr. GUYER, Mr. Mr. LUKEN, Mr. CHARLES WILSON Of Texas, MURPHY of Pennsylvania, Mr. BEVILL, Mr. HALL of Texas, Mr. HYDE, Mr. LOTT, Mr. Mr. LEDERER, Mr. LONG of Maryland, Mr. LUN MADIGAN, Mr. VENTO, Mr. HOLLENBECK, Mr. LUKEN, Mr. MARTIN, Mr. MOAKLEY, Mr. MONT DINE , Mr. AKAKA, Mr. RODINO , Mr. CLEVELAND, LAGOMARSINO, Mr. DIGGS, Mr. WILLIAMS O! GOMERY , Mr. ROBERTS, Mr. Russo, Mr. Rous Mr. DUNCAN of Tennessee, and Mr. RosE. Montana, Mr. PEPPER. Mr. FORD of Michigan, SELOT, Mr. SHUMWAY, Mrs. SPELLMAN, Mr. H.R. 1600: Mr. WHITEHURST, Mr. LAGOMAR Mr. MITCHELL of New York, Mr. GUYER , Mr. STOCKMAN, Mr. SYMMS, Mr. WALKER, Mr. SINO, Mr. RAHALL, Mr. WALKER, Mr. DAN MCCLOSKEY, Mr. RANGEL , Mr. WEISS, Mr. SI WHITEHURST, Mr. WYLIE, and Mr. ZEFERETTI. NEMEYER , Mr. ABDNOR, Mr. CONTE, Mr. HYDE , MON, Mr. FLOOD, Mr. LUKEN, Mr. GREEN, Mr. H. Res. 34: Mr. BUCHANAN, Mr. CAVANAUGH, Mr. ERTEL , Mr. SENSENBRENNER , Mr. HOWARD , OTTINGER, Mr. MOFFETT, Mr. DAVIS Of Michi Mr. CLINGER, Mr. CONTE , Mr. DIXON, Mr. DOR Mr. SEBELIUS , Mr. LLO YD, Mr. LOTT , Mr. KIND gan, Mr. HUGHES, Mrs. SPELLMAN, Mr. CARR, NAN, Mr. EDWARDS of Oklahoma, Mr. EVANS of NESS, Mr. MURPHY of Pennsylvania, Mr. BUR Mr. WINN, Mr. BLANCHARD, Mr. SCHEUER, Mr. Georgia, Mr. FINDLEY, Mr. GUARINI, Mr. HOL GEN ER, Mr. -

Conservative Judaism RESTRUCTURING THE

Volume XXVII, Number 4 Summer 1973 Conservative Judaism Published by the Rabbinical Assembly and The Jewish Theological Seminary of America Consevative Judaism, 3080 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10027. RESTRUCTURING THE SYNAGOGUE Harold M. Schulweis IT IS Now some twenty years since our teacher Abraham Joshua Heschel, alav ha-shalom, addressed this assembly and spoke these strong words: “The modern temple suffers from a severe cold . the services are prim, the voice is dry, the temple is clean and tidy . no one will cry, the words are stillborn.” The criticism was directed against the metallic services, against the lugubrious tones of the ritual master of ceremonies intoning the Siddur pagination. For us it was neither a novel nor a pleasant criticism. The complaint has long since taken on the acerbity of folk humor. A penetrating Jewish anecdote tells of a nouveau riche young man who invited his European traditionalist father to his modern temple. The son was proud of the decorum and, indeed, when the rabbi informed the congregation that they were to rise for the silent meditative prayer, there was a silence. With pride the son whispered to his father, “what do you think about that?" Papa responded in Yiddish, a mechayeh! Der rav steht un zogt gornisht un alle heren zich zu (The rabbi stands and says nothing, and everyone listens to him). What do they want of us rabbis? Are we not warm enough? The services are cold. Shall we raise the thermostat? The prayers lack relevance. Shall we experiment more? Should we add guitar or flute or harp to the organ? Should we gather new prayers from the liturgy of our Jewish theological trinity—Joan Baez, Rod McKuen and Khalil Gibran? Somehow the criticism and the apologia seem misdirected. -

On the Origins and Persistence of the Jewish Identity Industry in Jewish Education

Journal of Jewish Education ISSN: 1524-4113 (Print) 1554-611X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujje20 On the Origins and Persistence of the Jewish Identity Industry in Jewish Education Jonathan Krasner To cite this article: Jonathan Krasner (2016) On the Origins and Persistence of the Jewish Identity Industry in Jewish Education, Journal of Jewish Education, 82:2, 132-158, DOI: 10.1080/15244113.2016.1168195 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15244113.2016.1168195 Published online: 16 May 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 360 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 5 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ujje20 JOURNAL OF JEWISH EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 82, NO. 2, 132–158 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15244113.2016.1168195 On the Origins and Persistence of the Jewish Identity Industry in Jewish Education Jonathan Krasner ABSTRACT “Jewish identity,” which emerged as an analytical term in the 1950s, appealed to a set of needs that American Jews felt in the postwar period, which accounted for its popularity. Identity was the quintessential conundrum for a community on the threshold of acceptance. The work of Kurt Lewin, Erik Erikson, Will Herberg, Marshall Sklare, and others helped to shape the communal conversation. The reframing of that discourse from one that was essentially psychosocial and therapeutic to one that was sociological and survivalist reflected the community’s growing sense of physical and socioeconomic security in the 1950s and early 1960s.