Trust and Trustworthiness in Procurement Contracts with Retainage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Babcock & Wilcox Enterprises, Inc

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 001-36876 BABCOCK & WILCOX ENTERPRISES, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 47-2783641 (State or other Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 1200 East Market Street, Suite 650 Akron, Ohio 44305 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (330) 753-4511 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $0.01 par value BW New York Stock Exchange 8.125% Senior Notes due 2026 BWSN New York Stock Exchange Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Green Building: Design and Construction Contract Issues

May 8, 2012 Green Building: Design and Construction Practice Groups: Contract Issues Construction and Engineering By Gregory R. Andre Real Estate Investment, “Green Buildings” feature energy efficient and environmentally friendly elements. Governmental Development and regulation, cost savings and public relations are driving the trend. While architects, engineers, Finance contractors and facilities managers focus on Green Building design, construction, equipment and operation issues, lawyers may wish to consider Green Building issues in the contracts entered into between the owner and the design and construction professionals. This article addresses the special contract issues that may arise in connection with the design and construction of Green Buildings. A. Introduction Green Buildings generally refer to those that are designed and constructed in an environmentally friendly manner. Specifically, it refers to buildings that are located and landscaped so as to minimize ecological impact and maximize conservation and biodiversity; building design and construction that is efficient in the use of energy, water and other resources and materials; and building operation that provides a healthy, high quality indoor environment. The concept of rating or certifying buildings with respect to environmental issues originated in the United Kingdom in 1990 by the Building Research Establishment’s Environmental Assessment Method, which has come to be known collectively as “BREEAM”. BREEAM, or variations of it, are found in many other countries today. In 1998, the U.S. Green Building Council (“USGBC”), a non-profit organization, developed the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (“LEED”) Green Building Certification System for rating the design, construction and operation of buildings. LEED provides four levels of certification: certified, silver, gold and platinum. -

Report by the Construction Law Committee Improving

CONTACT POLICY DEPARTMENT MARIA CILENTI 212.382.6655 | [email protected] ELIZABETH KOCIENDA 212.382.4788 | [email protected] REPORT BY THE CONSTRUCTION LAW COMMITTEE IMPROVING NEW YORK CITY’S DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION PROCESSES AND PRACTICES I. INTRODUCTION Construction, infrastructure and the built environment are back in the public spotlight once again. The American Society of Civil Engineers has recently released its 2017 Infrastructure Report Card, assigning an overall grade of D+ to the state of good repair of American infrastructure and a C- to the state of good repair of New York State’s infrastructure.1 The Trump administration has also made infrastructure expansion and state of good repair a national priority. The Construction Law Committee of the New York City Bar Association (the Committee) has, since 2008, been actively analyzing how New York State’s laws pose impediments to all New York state and local government owners in their efforts to make their systems operate in a state of good repair and expand to meet stakeholder needs in the most efficient manner possible.2 The Committee has specifically focused on State laws affecting design and construction practice and delivery. With this report, the Committee shifts its attention from New York State (State) laws to New York City (City) laws that provide opportunities for the City to improve its design and construction processes and practices. By focusing exclusively on areas where the City is not constrained by State laws, the Committee has identified opportunities for changes in local laws, policies and practices within the City’s administrative control that, in the Committee’s opinion, would increase process efficiency and permit City agencies to avoid unnecessary costs caused by the status quo. -

High Performance Building Guidelines

Executive Acknowledgements Honorable Rudolph W. Giuliani Mayor City of New York Luis M. Tormenta, P.E. Commissioner New York City Department of Design and Construction Michael Burton, P.E. Deputy Commissioner New York City Department of Design and Construction Hillary Brown, AIA Assistant Commissioner New York City Department of Design and Construction Fredric Bell, AIA Assistant Commissioner New York City Department of Design and Construction Andrea Woodner Founding Director Design Trust for Public Space Commissioner’s Foreword To the Reader: As we enter the new century, the City of New York is in a unique position to improve the overall quality and performance of public buildings that are constructed and renovated by the Department of Design and Construction (DDC). We can do that by increasing our reliance on energy and environmentally efficient construction technologies and practices, by taking advantage of the strides that have been made over the past few years in the field of ‘green buildings.‘ Key to the success of that effort is our ability to make responsible investments to improve the environment without constraining economic activity. We are now in a position to do that, and, under the leadership of Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani, are moving ahead to make New York City an environmental prototype for the 21st Century. These Guidelines outline strategies and techniques that can move us toward that goal. They set out a range of ’best practices‘ for planning, designing, constructing and operating healthier, more energy – and resource – efficient facilities. Such high performance buildings can earn long term life cycle savings for New York City, and may also help stimulate the markets for environmentally efficient technologies. -

Construction Law

Mercer Law Review Volume 46 Number 1 Annual Survey of Georgia Law Article 6 12-1994 Construction Law Brian J. Morrissey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/jour_mlr Part of the Construction Law Commons Recommended Citation Morrissey, Brian J. (1994) "Construction Law," Mercer Law Review: Vol. 46 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/jour_mlr/vol46/iss1/6 This Survey Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Mercer Law School Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mercer Law Review by an authorized editor of Mercer Law School Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Construction Law by Brian J. Morrissey* I. INTRODUCTION As the construction industry moved through its recession, a number of issues eventually percolated their way through the appellate courts. Not surprisingly, once projects began going under, many of these cases focused on novel theories seeking to impose liability against "deep pockets." The most significant event during the survey period was the develop- ment of a unique approach to impose liability against the government for the insolvency of sureties presented on public works projects, and the abrupt reversal of the adoption of this theory by the Georgia Supreme Court. Also during the survey period, there were a number of attempts to impose liability against lenders on construction projects for the failure to ensure that payments were made to contractors in such a way as to avoid the imposition of liens, and on commitments to keep construction loans flowing. -

Supreme Court No

FILED Court of Appeals Division I State of Washington 3/19/2020 3:44 PM Supreme Court No. _____98318-6 _ SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON No. 78753-5-1 COURT OF APPEALS, DIVISION ONE, OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON STATE CONSTRUCTION, INC., Petitioner V. CITY OF SAMMAMISH, a governmental entity, PORTER BROTHERS CONSTRUCTION, INC., a Washington Corporation, HARTFORD FIRE INSURANCE COMPANY, a Corporation, and Bond No. 52BCSDL 1582, Respondents PETITION FOR REVIEW Morgan J. Wais, WSBA# 36603 Matthew M. Kennedy, WSBA #36452 Douglas W. Scott, WSBA #6658 RAINIER LEGAL ADVOCATES, LLC 465 Rainier Blvd. N., Suite C Issaquah, WA 98027 ( 425) 392-8550 (425) 392-2829 (fax) Attorneys for Petitioner TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................................ 11 I. INTRODUCTION....................................................... I II. IDENTITY OF PETITIONER . .. ... I III. COURT OF APPEALS DECISION............................... I IV. ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW........................... 2 V. STATEMENT OF THE CASE....................................... 2 VI. ARGUMENT WHY REVIEW SHOULD BE ACCEPTED. 7 A. Summary of Argument......................................... 7 B. RCW 60.28.011: "Completion of the Contract Work" May Only Occur Upon the Public Body's Acceptance of the Project.......................................................... 9 I. The Retainage Statute Should be Given its Intended Effect........................................................ 9 2. The Court of Appeals' Analysis and Conclusions Were in Error. 14 C. Due Process: A Subcontractor Must Have Notice of the Date Commencing The Retainage Claims Period and a Meaningful Opportunity to File Retainage Claims...... 16 D. Attorneys Fees: Bond and Retainage Claims Only Allow Attorney's Fees to the Claimant..................... 19 VII. CONCLUSION....................................................... 20 Page i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Tables of Cases Arbonvood Idaho, LLC v. -

July/August 2018 Edition

NEWSLETTER THE SURETY & FIDELITY ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA VOLUME XXXV, ISSUE 5, JULY/AUGUST 2018 The Hunt For Talent Lee Covington to Lead SFAA “In the past 22 years, Lynn products and services offered by Schubert has transformed the SFAA the association’s members,” said into the thought leader and trusted Covington. adviser for the surety and fidelity Covington currently is the Senior industry, as well as for government Vice President, Governmental Affairs agencies and legislators,” said and General Counsel for the Insured Board Chair Larry Taylor. “Now the Retirement Institute, a position industry marks the beginning of a he held since 2009, leading its new era with Lee Covington.” legislative and regulatory initiatives The SFAA works every day to at both the federal and state levels. educate lawmakers and stakeholders His focus on insurance law began about the benefits of surety and in 1993 in Little Rock, Arkansas fidelity bonding and the critical where he rose to become the deputy role it plays to protect public and commissioner of the Arkansas private interests. In 2017 alone, the Insurance Department. Covington surety industry provided over $600 honed his leadership skills as the billion in protection to consumers, Director of the Ohio Department taxpayers and businesses. The of Insurance from 1999 to 2002, organization represents more than where he served on the Executive 425 property and casualty insurance Committee of National Association companies providing public policy of Insurance Commissioners, and The Surety & Fidelity Association advocacy and education, as well then moved to positions of influence of America’s (SFAA) board of as statistical and actuarial services on the national stage in Washington directors is delighted to announce and information. -

New York Lien Law and Insurance For

NEW YORK LIEN LAW AND INSURANCE FOR NSTITUTE CONSTRUCTION I PROJECTS: A PRACTICAL LOOK Prepared in connection with a Continuing Legal Education course presented CLE at New York County Lawyers’ Association, 14 Vesey Street, New York, NY scheduled for February 26, 2015 Program Co-sponsors: NYCLA Construction Law Committee, Insurance Law Committee and Real Estate Section Program Chair: Ariel Weinstock, Katsy Korins LLP Faculty: Thomas Donohue, Baldon Group, Inc. Insurance; Al Stork, Lex Terrae Ltd/Old Republic National Title Insurance Company NYCLA This course has been approved in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 3 Transitional and Non-Transitional credit hours: 2 Professional Practice/Law Practice Management; 1 Skills. This program has been approved by the Board of Continuing Legal education of the Supreme Court of New Jersey for 3 hours of total CLE credits. Of these, 0 qualify as hours of credit for ethics/professionalism, and 0 qualify as hours of credit toward certification in civil trial law, criminal law, workers compensation law and/or matrimonial law. ACCREDITED PROVIDER STATUS: NYCLA’s CLE Institute is currently certified as an Accredited Provider of continuing legal education in the States of New York and New Jersey. Information Regarding CLE Credits and Certification New York Lien Law and Insurance for Construction Projects: A Practical Look February 26, 2015; 6:00 PM to 9:00 PM The New York State CLE Board Regulations require all accredited CLE providers to provide documentation that CLE course attendees are, in fact, present during the course. -

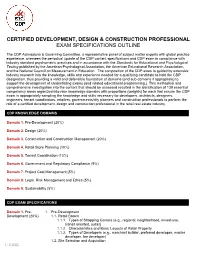

Cmd Examination Content

CERTIFIED DEVELOPMENT, DESIGN & CONSTRUCTION PROFESSIONAL EXAM SPECIFICATIONS OUTLINE The CDP Admissions & Governing Committee, a representative panel of subject matter experts with global practice experience, oversees the periodical update of the CDP content specifications and CDP exam in compliance with industry standard psychometric practices and in accordance with the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing published by the American Psychological Association, the American Educational Research Association, and the National Council on Measurement in Education. The composition of the CDP exam is guided by extensive industry research into the knowledge, skills and experience needed for a qualifying candidate to hold the CDP designation, thus providing a valid and defensible foundation of domains (and sub-domains if appropriate) to support the development of credentialing exams (and related educational programming.) This methodical and comprehensive investigation into the content that should be assessed resulted in the identification of 139 essential competency areas organized into nine knowledge domains with proportions (weights) for each that ensure the CDP exam is appropriately sampling the knowledge and skills necessary for developers, architects, designers, engineers, tenant coordinators, retailers, governments/city planners and construction professionals to perform the role of a certified development, design and construction professional in the retail real estate industry. CDP KNOWLEDGE DOMAINS Domain 1. Pre-Development (20%) Domain 2. Design (20%) Domain 3. Construction and Construction Management (20%) Domain 4. Retail Store Planning (10%) Domain 5. Tenant Coordination (10%) Domain 6. Government and Regulatory Compliance (5%) Domain 7. Project Cost Management (5%) Domain 8. Legal, Risk Management and Ethics (5%) Domain 9. Sustainability (5%) CDP EXAM SPECIFICATIONS Domain 1. -

Joseph A. Curtatone, Mayor

IFB # 19-91 REBID SOLICITATION FOR: Allen Street Playground Construction CITY OF SOMERVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS Joseph A. Curtatone, Mayor Purchasing Department Angela M. Allen, Purchasing Director RELEASE DATE: 8/28/2019 QUESTIONS DUE: 9/4/2019 by 5PM ET DUE DATE AND TIME: 9/12/2019 by 1:30PM ET DELIVER TO: City of Somerville Purchasing Department Attn: Michael Richards Assistant Purchasing Director [email protected] 93 Highland Avenue Somerville, MA 02143 1 IFB # 19-91 REBID Allen Street Playground Construction Key Project Information Project Address Allen St., Somerville, MA Estimated Construction Cost $185,000.00 Anticipated Contract Award 9/18/2019 Date of Substantial Completion 6/1/2020 Date of Final Completion 7/15/2020 Est. Contract Commencement 10/1/2019 Date Est. Contract Completion Date 8/30/2020 Governing Bid Law MGL 30.39M (Horizontal Construction) Wage Requirements The higher of Federal Davis Bacon Wages and State Prevailing Wages Payment Bond Requirements 50% of Contract Value Performance Bond N/A Requirements Liquidated Damages ($ per $250.00 Day) Managing Department Information Managing City Department Office of Strategic Planning and Community Development Project Manager Arn Franzen Project Manager Email [email protected] Designer Information Designer Name TerraInk, Inc. Designer Address 7 Central Street, Suite 150, Arlington, MA 02476 Designer Specialty Landscape Architecture Designer Contact Jade Cummings Designer Contact Email [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1: INVITATION FOR BID DOCUMENTS -

Electronic Council Packet for 06-12-2018

AUDIT COMMITTEE MEETING TUESDAY, JUNE 12, 2018 1:00 P.M. CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM, CITY HALL, ROOM 290 200 TEXAS STREET, FORT WORTH, TEXAS LONE STAR LOCAL GOVERNMENT CORPORATION MEETING TUESDAY, JUNE 12, 2018 1:30 P.M. CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM, CITY HALL, ROOM 290 200 TEXAS STREET, FORT WORTH, TEXAS FORT WORTH LOCAL DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION MEETING TUESDAY, JUNE 12, 2018 (IMMEDIATELY FOLLOWING THE LONE STAR LOCAL GOVERNMENT CORPORATION MEETING) CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM, CITY HALL, ROOM 290 200 TEXAS STREET, FORT WORTH, TEXAS INFRASTRUCTURE AND TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE MEETING TUESDAY, JUNE 12, 2018 2:00 P.M. CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM, CITY HALL, ROOM 290 200 TEXAS STREET, FORT WORTH, TEXAS CITY COUNCIL WORK SESSION TUESDAY, JUNE 12, 2018 3:00 P.M. CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM, CITY HALL, ROOM 290 200 TEXAS STREET, FORT WORTH, TEXAS 1. Report of the City Manager - David Cooke, City Manager a. Changes to the City Council Agenda b. Upcoming and Recent Events c. Organizational Updates and Employee Recognition(s) d. Informal Reports IR 10157: April 2018 - Sales Tax Update IR 10158: Proposed Zoning Ordinance Text Amendment for Certain Commission Appointments IR 10159: Proposed Zoning Ordinance Text Amendment for Urban Residential (UR) 2. Current Agenda Items - City Council Members 3. Responses to Items Continued from a Previous Week 4. Briefing on Non-Discrimination Compliance Program - Angela Rush, City Manager's Office 1 of 2 5. Briefing on Annual Action Plan and Five-Year Consolidated Plan for Housing and Community Development Programs - Barbara Asbury, Neighborhood Services 6. Overview of Purchasing Rules & Regulations and Update on Implementation of PeopleSoft for Purchasing - Cynthia Garcia, Purchasing Division 7. -

Thousands Gather for King Tribute Troops Casket on Mule-Drawn Wagon ATLANTA, Ga

Governor Vetoes Bill on Third U.S. District -SEE STORY PAGE H Sunny, Mild HOME Sunny and mild today, high in THEDMLY 70s. Clear tonight) low in 40s. Bed Bank, Freehold Tomorrow, mostly sunny and FINAL mild. Long Brandt 7 S«t details page 2 Monmouth County*s Home Newspaper for 89 Years DIAL 741-0010 VOL. 90, NO. 198 RED BANK, N. J., TUESDAY, APRIL 9, 1968 TEN CENTS Thousands Gather for King Tribute Troops Casket on Mule-Drawn Wagon ATLANTA, Ga. (AP) — A Ibenezer Baptist Church After the service, thousands tege will go by car to the South Curbing farm wagon drawn by two where King was co-pastor with of mourners planned to march View Cemetery, five miles Georgia mules carries the body his father. through the streets in proces- from the college, where King of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Mrs. John F. Kennedy was sion behind the mule-drawn will be entombed in a marble through Atlanta streets today among the 1,300 invited to the wagon containing King's body mausoleum on a grassy hill- Violenc< as part of funeral services for services led by King's associ- for a 2 p.m. public service in side. By THE ASSOCIATED PpSS the slain civil rights leader. ate and SCLC successor, the the quadrangle of Morehouse Other officials among the Some 61,000 National Guards- King, apostle of nonviolence Rev. Ralph Abernathy, and the College. thousands of mourners in At- men and Army troops were de- through a decade of discontent, Rev. William Holmes Borders.