MARINE BIRD SURVEYS in QC STRAIT-Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

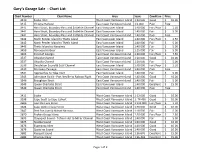

Gary's Charts

Gary’s Garage Sale - Chart List Chart Number Chart Name Area Scale Condition Price 3410 Sooke Inlet West Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3415 Victoria Harbour East Coast Vancouver Island 1:6 000 Poor Free 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3443 Thetis Island to Nanaimo East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3459 Nanoose Harbour East Vancouver Island 1:15 000 Fair $ 5.00 3463 Strait of Georgia East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 7.50 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Fair $ 5.00 3538 Desolation Sound & Sutil Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3539 Discovery Passage East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3541 Approaches to Toba Inlet East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3545 Johnstone Strait - Port Neville to Robson Bight East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Good $ 10.00 3546 Broughton Strait East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Excellent $ 15.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

Psc Draft1 Bc

138°W 136°W 134°W 132°W 130°W 128°W 126°W 124°W 122°W 120°W 118°W N ° 2 6 N ° 2 DR A F T To navigate to PSC Domain 6 1/26/07 maps, click on the legend or on the label on the map. Domain 3: British Columbia R N ° k 0 6 e PSC Region N s ° l Y ukon T 0 e 6 A rritory COBC - Coastal British Columbia Briti sh Columbia FRTH - Fraser R - Thompson R GST - Georgia Strait . JNST - Johnstone Strait R ku NASK - Nass R - Skeena R Ta N QCI - Queen Charlotte Islands ° 8 5 TRAN N TRAN - Transboundary Rivers in Canada ° 8 r 5 ive R WCVI - Western Vancouver Island e in r !. City/Town ik t e v S i Major River R t u k Scale = 1:6,750,000 Is P Miles N ° 0 30 60 120 180 January 2007 6 A B 5 N ° r 6 i 5 C t i s . A h R Alaska l I b C s e F s o a NASK r l N t u a r m I e v S i C tu b R a i rt a N a ° Prince Rupert en!. R 4 ke 5 !. S Terrace iv N e ° r 4 O F 5 !. ras er C H Prince George R e iv c e QCI a r t E e . r R S ate t kw r lac Quesnel A a B !. it D e an R. N C F N COBC h FRTH ° i r 2 lc a 5 o N s ti ° e n !. -

PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition 46 W Puget Sound – Point Partridge to Point No Point 50,000 Aug

Natural Date of New Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition 46 w Puget Sound – Point Partridge to Point No Point 50,000 Aug. 1995 July 2005 Port Townsend 25,000 47 w Puget Sound – Point No Point to Alki Point 50,000 Mar. 1996 Sept. 2003 Everett 12,500 48 w Puget Sound – Alki Point to Point Defi ance 50,000 Dec. 1995 Aug. 2011 A Tacoma 15,000 B Continuation of A 15,000 50 w Puget Sound – Seattle Harbor 10,000 Mar. 1995 June 2001 Q1 Continuation of Duwamish Waterway 10,000 51 w Puget Sound – Point Defi ance to Olympia 80,000 Mar. 1998 - A Budd Inlet 20,000 B Olympia (continuation of A) 20,000 80 w Rosario Strait 50,000 Mar. 1995 June 2011 1717w Ports in Juan de Fuca Strait - July 1993 July 2007 Neah Bay 10,000 Port Angeles 10,000 1947w Admiralty Inlet and Puget Sound 139,000 Oct. 1893 Sept. 2003 2531w Cape Mendocino to Vancouver Island 1,020,000 Apr. 1884 June 1978 2940w Cape Disappointment to Cape Flattery 200,000 Apr. 1948 Feb. 2003 3125w Grays Harbor 40,000 July 1949 Aug. 1998 A Continuation of Chehalis River 40,000 4920w Juan de Fuca Strait to / à Dixon Entrance 1,250,000 Mar. 2005 - 4921w Queen Charlotte Sound to / à Dixon Entrance 525,000 Oct. 2008 - 4922w Vancouver Island / Île de Vancouver-Juan de Fuca Strait to / à Queen 525,000 Mar. 2005 - Charlotte Sound 4923w Queen Charlotte Sound 365,100 Mar. -

Archeological Evidence of Large Northern Bluefin Tuna

I J Abstract.-This study presents ar cheological evidence for the presence of Archeological evidence of large adult bluefin tuna. Thunnus thynnus, northern bluefin tuna, in waters off the west coast of British Columbia and northern Washington State for the past 5,000 years. Skeletal Thunnus thynnus, in coastal remains oflarge bluefin tuna have been waters of British Columbia and recovered from 13 archeological sites between the southern Queen Charlotte northern Washington Islands, British Columbia. and Cape Flattery, Washington, the majority found on the west coast of Vancouver Susan Janet Crockford Island. Vertebrae from at least 45 fish from 8 Pacific Identifications sites were analyzed. Regression analy 601 J Oldfield Rd .. RR #3. Victoria. British Columbia. Canada vax 3XI sis <based on the measurement and E-mail address:[email protected] analysis ofmodern skeletal specimens) was used to estimate fork lengths ofthe fish when alive; corresponding weight and age estimates were derived from published sources. Results indicate that bluefin tuna between at least 120 and Evidence is presented here for the maining 5 sites could not be exam 240 em total length <TLJ (45-290 kg) occurrence of adult bluefin tuna, ined, owing largely to difficulties in were successfully harvested by aborigi Thunnus thynnus, in waters ofthe retrieving archived specimens but, nal hunters: 83% ofthese were 160 em northeastern Pacific, off the coast in one case, because all skeletal TL or longer. Archeological evidence is of British Columbia and northern material had been discarded by augmented by the oral accounts ofna tive aboriginal elders who have de Washington, for the past 5,000 museum staID. -

Environment and Economy in the Finnish-Canadian Settlement of Sointula

Utopians and Utilitarians: Environment and Economy in the Finnish-Canadian Settlement of Sointula M IKKO SAIKKU There – where virgin nature, unaltered by human hand, exudes its own, mysterious life – we shall find the sweet feeling that terrifies a corrupt human being, but makes a virtuous one sing with poetic joy. There, amidst nature, we shall find ourselves and feel the craving for love, justice, and harmony. Matti Kurikka, 19031 he history of Sointula in British Columbia – the name of the community is a Finnish word roughly translatable as “a place of harmony” – provides ample material for an entertaining T 1901 narrative. The settlement was founded in as a Finnish utopian commune on the remote Malcolm Island in Queen Charlotte Strait. Al- though maybe a quarter of Malcolm Island’s eight hundred inhabitants are still of Finnish descent, little Finnish is spoken in the community today.2 Between the 1900s and the 1960s, however, the predominant language of communication in Sointula was Finnish. The essentials of Sointula’s fascinating history are rather well known: they include the establishment of an ethnically homogenous, utopian socialist commune; its inevitable breakup; strong socialist and co-operative 1 I wish to thank Pirkko Hautamäki, Markku Henriksson, Kevin Wilson, the editor of BC Studies, and two anonymous readers for their thoughtful comments on the manuscript. A 2004 travel grant from the Chancellor’s Office at the University of Helsinki and a 2005 Foreign Affairs Canada Faculty Research Award enabled me to conduct research in British Columbia. Tom Roper, Gloria Williams, and other staff at the Sointula Museum were most supportive of my research on Malcolm Island, while Jim Kilbourne and Randy Williams kindly provided me with the hands-on experience of trolling for Pacific salmon onboard the Chase River. -

The Kwakwaka'wakw

NAT IONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN THE KWAKWAKA’WAKW A STUDY OF A NORTH PACIFIC COAST PEOPLE AND THE POTLATCH Grade Levels: 6–8 Time Required: 3 class periods OVERVIEW CURRICULUM STANDARDS FOR In this poster students will learn about the Kwakwaka’wakw SOCIAL STUDIES (pronounced: kwock-KWOCKY-wowk) people of British Culture (I), Time, Continuity, and Change (II), People, Columbia, Canada. The focus is on Kwakwaka’wakw traditions Places, and Environments (III) that express concepts of wealth, values of giving, and the importance of cultural continuity. Students will learn about OBJECTIVES the Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch practice: its history, the values In the lessons and activities, students will: inherent in it, and the important role it plays in establishing Learn about the Kwakwaka’wakw people, culture, and values and maintaining family connections to the past, to ancestors, Learn about the practice of the potlatch and its history and to the spirits of all living things. Students will use Understand Kwakwaka’wakw concepts of wealth and value Kwakwaka’wakw concepts and discuss differences in value systems. For an audio pronunciation guide, visit our website: www.AmericanIndian.si.edu/education. BACKGROUND Native peoples maintain close connections to the land and the places they come from. They express those connections in many different ways, including ceremonies and celebrations that can involve singing and dancing, giving thanks, feasting, gift giving, storytelling, and games. In the United States and Canada, there are more than 1,100 individual tribes—each with its own set of practices that show appreciation for the natural world and those spirits that lie within it. -

Marine Atlas of Pacific Canada 142°W 140°W 138°W 136°W 134°W 132°W 130°W 128°W 126°W 124°W 122°W

Physical Representation – Ecosections description data sources This atlas page illustrates the 12 marine ecosections delineated by the Province of British Columbia in 2000. Ecosections are recognized by • Province of British Columbia a hierarchical ecological mapping system called the British Columbia Marine Ecological Classification (BCMEC) and defined according to physical, oceanographic and biological characteristics. They are a very useful delineation in a physical sense in that they have been mapped with data resolution a focus on identifying physical differences that will tend to affect species distributions within a bio-geographic region. • Ecosections are mapped at small scales (1:250,000) for resource emphasis and area planning. date of analysis • 2000 (published in 2002) reviewers • Kim Conway, Natural Resources Canada • Zach Ferdana, The Nature Conservancy reviewer comments PHOTO: CHARLIEPHOTO: SHORT PHOTO: ROBERT SIMON ROBERT PHOTO: • None provided. caveats of use • The Province of BC is not liable for errors in the data or inappropriate usage of the data. • Recommended date of expiry for use of these data in a marine planning context: None provided. map, feature data and metadata access • Visit www.bcmca.ca/data for more information. references • For more detailed information on the Marine Ecosections of British Columbia see: Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management (MSRM), Decision Support Services Branch. British Columbia Marine Ecological Classification Marine Ecosections and Ecounits, Version 2.0. Report prepared for -

The Distribution of Certain Benthonic Algae in Queen Charlotte Strait, British Columbia, in Relation to Some Environmental Factors

The Distribution of Certain Benthonic Algae in Queen Charlotte Strait, British Columbia, in Relation to Some Environmental Factors ROBERT F. SCAGEL 1 IN COMPARISON with the progress in our knowl cially of members of the Laminariales on the edge of most groups of plants-especially con Pacific Coast of North America, on the basis of cerning their life histories and distributions latitudinal and seasonal temperature distribu the advances made in marine phycology and tions. The physical data available during this marine ecology have been relatively slow. The early period were limited, but many of the prin limited access to living material or to the facil ciples set forth by Setchell concerning the dis ities to maintain the larger marine algae in the tributions of marine algae are as sound now as living condition for a prolonged period of time, when they were first proposed. Except for more the difficulties of collection-particularly in the precise knowledge of the physical and chemical subtidal zone-and the lack of any extensive factors of the environment and the distribu direct economic importance until recent years tions of the algae concerned, much of Setchell's have all contributed to this slow progress. How ecological work can still be used as a good ever, in spite of these difficulties there has been foundation for further study. Although it was a considerable amount of interest in the marine largely a two-dimensional approach to the algae, including a number of studies of their marine environment, Setchell's work made a ecology. Although this interest has been fairly significant contributiOn to the development of widespread in a number of countries, until re marine algal ecology. -

Natural History Feeding

BRITISH COLUMBIA VANCOUVER ISLAND GEOLOGY The Creation of the Johnstone Strait Over a span of thousands of years and a combination of processes such as tectonics, volcanism, erosion and glaciation the 110km Johnstone Strait off of Vancouver Island was formed. Formally known as Wrangellia, a land mass that collided with North America causing it to fold and buckle forming the many of the mountains and ranges we associate with British Columbia today. The formation of the narrow channels that make up Northeastern Vancouver Island dates back to the ice ages when glacial ice sheets settled in the area. During the Pleistocene Epoch Ice Age ice sheets carved their way through the igneous rock or the channel creating what is now known as Johnstone Strait, Queen Charlotte strait, and the Discovery Passage. Glacial carving transpires through the slow movement of the ice sheet. Due to their sheer size and weight combined with gravity ice sheets move slowly down mountain valleys, and across plains. As glaciers move they sculpt the land via erosion and deposition. While they gradually move across the landscape the ice erodes the surface beneath it, creating fjords, glacial valleys, and horns. During this erosion the ice actually picks up and retains sediment and particles depositing them along the way. This process of deposition, depositing of material as the glacier retreats and melts away, forms moraines which are narrow ridges that show where the ice used to be. Robson Bight Ecological Reserve ceremonial purposes. Ubiquitous to the area are manmade geological features known as clam beds. For the First Nations’ people clams were a staple not only for their food source but for their economy as Ecological Reserves were formed in Canada in 1971 as a way to encourage the preservation of natural well for they used them in trade with other tribes. -

1 Endemics of Southeast Alaska and Adjacent British Columbia

Endemics of Southeast Alaska and Adjacent British Columbia Common Name Scientific Name Distribution Habitat TNF District ADFG Comments References GMU LICHENS and FUNGI Amygdalaria continua Endemic to southeast Subalpine rocks Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska and Haida Gwaii Amygdalaria haidensis Endemic to southeast Rocky habitats Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska and Haida Gwaii Bryoria carlottae Endemic to BC and Primarily on shore Geiser et al. (1998) southeast Alaska pine and western hemlock in low elevation peatlands and open mixed forests. Bryoria cervinula Endemic to BC and Primarily on open Geiser et al. (1998) southeast Alaska grown shore pine and western hemlock, from low elevations to subalpine. Placopsis roseonigra Endemic to southeast Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska (Sitka, Juneau) and Haida Gwaii Rhizocarpon hensseniae Endemic to southeast On alpine rocks Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska and Haida Gwaii Tremella hypogymniae NW of Haines Lichenicolous fungus Juneau RD GMU 1D Only other NA reports of this species Geiser et al. (1998) on Hypogymnia are from Ontario, Canada physodes. Verrucaria schofieldii Endemic to southeast On littoral rock. Recently described Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska and Haida Gwaii MOSSES Carey small Seligeria careyanna Endemic to Moresby I., Limestone cliffs www.forestbiodive limestone moss Haida Gwaii rsityinbc.ca a peat moss Sphagnum wilfii The type locality of this Pine bogs at low to This species is on the British http://www.efloras. species is in Haida moderate elevations Columbia RED list (endangered or org Gwaii. It has been threatened). collected only infrequently but is fairly common in southeast Alaska. VASCULAR PLANTS upswept moonwart Botrychium ascendens In Alaska, known only Mesic meadows and Yakutat RD GMU 5 Lipkin and Murray from Yakutat and Glacier sandy sites near sea (1997) Bay; elsewhere, from a level. -

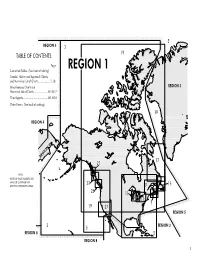

Index to NGA Charts, Region 1

1 2 REGION 1 COASTAL CHARTS Stock Number Title Scale =1: 11004 Mississippi River to Rio Grande 866,500 14003 Cape Race to Cape Henry 1,532,210 14018 The Grand Banks of Newfoundland and the Adjacent Coast 1,200,000 14024 Island of Newfoundland 720,240 15017 Hudson Strait (OMEGA) 1,000,000 15018 Belle Isle to Resolution Island (OMEGA) 1,000,000 15020 Hudson Strait to Greenland 1,501,493 15023 Queen Elizabeth Islands - Southern Part and Adjacent Waters 1,000,000 16220 St. Lawrence Island to Bering Strait 315,350 17003 Strait of Juan de Fuca to Dixon Entrance 1,250,000 18000 Point Conception to Isla Cedros 950,000 19008 Hawaiian Islands (OMEGA-BATHYMETRIC CHART) 1,030,000 38029 Baffin Bay (OMEGA) 917,000 38032 Godthabsfjord to Qeqertarsuaq including Cumberland Peninsula 841,000 38280 Kennedy Channel-Kane Basin to Hall Basin 300,000 38300 Smith Sound and Kane Basin 300,000 38320 Inglefield Bredning &Approaches 300,000 96028 Poluostrov Kamchatka to Aleutian Islands including Komandorskiye Ostrova 1,329,300 96036 Bering Strait (OMEGA) 928,770 3 4 REGION 1 COASTAL CHARTS EAST AND WEST COASTS-UNITED STATES Stock Number Title Scale =1: 11461 Straits of Florida-Southern Portion 300,000 13264 Approaches to Bay of Fundy 300,000 17005 Vancouver Island 525,000 17008 Queen Charlotte Sound to Dixon Entrance 525,000 17480 Queen Charlotte Sound 365,100 18766 San Diego to Islas De Todos Santos (LORAN-C) 180,000 5 6 NOVA SCOTIA AREA Stock Number Title Scale =1: Stock Number Title Scale =1: 14061 Grand Manan (Bay of Fundy) 60,000 14136 Sydney Harbour 20,000 14081 Medway Harbour to Lockeport Harbour including Liverpool 80,000 Plans: A.