The Kwakwaka'wakw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

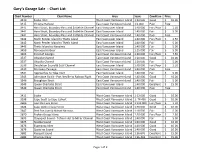

Gary's Charts

Gary’s Garage Sale - Chart List Chart Number Chart Name Area Scale Condition Price 3410 Sooke Inlet West Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3415 Victoria Harbour East Coast Vancouver Island 1:6 000 Poor Free 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3443 Thetis Island to Nanaimo East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3459 Nanoose Harbour East Vancouver Island 1:15 000 Fair $ 5.00 3463 Strait of Georgia East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 7.50 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Fair $ 5.00 3538 Desolation Sound & Sutil Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3539 Discovery Passage East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3541 Approaches to Toba Inlet East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3545 Johnstone Strait - Port Neville to Robson Bight East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Good $ 10.00 3546 Broughton Strait East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Excellent $ 15.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East -

A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia's Central Coast

A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia’s Central Coast REPORT · 2021 citation Atlas, W. I., K. Connors, L. Honka, J. Moody, C. N. Service, V. Brown, M .Reid, J. Slade, K. McGivney, R. Nelson, S. Hutchings, L. Greba, I. Douglas, R. Chapple, C. Whitney, H. Hammer, C. Willis, and S. Davies. (2021). A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia’s Central Coast. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Pacific Salmon Foundation. authors Will Atlas, Katrina Connors, Jason Slade Rich Chapple, Charlotte Whitney Leah Honka Wuikinuxv Fisheries Program Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance Salmon Watersheds Program, Wuikinuxv Village, BC Campbell River, BC Pacific Salmon Foundation Vancouver, BC Kate McGivney Haakon Hammer, Chris Willis North Coast Stock Assessment, Snootli Hatchery, Jason Moody Fisheries and Oceans Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Nuxalk Fisheries Program Bella Coola, BC Bella Coola, BC Bella Coola, BC Stan Hutchings, Ralph Nelson Shaun Davies Vernon Brown, Larry Greba, Salmon Charter Patrol Services, North Coast Stock Assessment, Christina Service Fisheries and Oceans Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Kitasoo / Xai’xais Stewardship Authority BC Prince Rupert, BC Klemtu, BC Ian Douglas Mike Reid Salmonid Enhancement Program, Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Fisheries and Oceans Canada Management Department Bella Coola, BC Bella Bella, BC published by Pacific Salmon Foundation 300 – 1682 West 7th Avenue Vancouver, BC, V6J 4S6, Canada www.salmonwatersheds.ca A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia’s Central Coast REPORT 2021 Acknowledgements We thank everyone who has been a part of this collaborative Front cover photograph effort to develop a salmon monitoring and stewardship and photograph on pages 4–5 framework for the Central Coast of British Columbia. -

Songhees Pictorial

Songhees Pictorial A History ofthe Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790 - 1912 by Grant Keddie Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, 2003. 175pp., illus., maps, bib., index. $39.95. ISBN 0-7726-4964-2. I remember making an appointment with Dan Savard in or der to view the Sali sh division ofthe provincial museum's photo collections. After some security precautions, I was ushered into a vast room ofcabi nets in which were the ethnological photographs. One corner was the Salish division- fairly small compared with the larger room and yet what a goldmine of images. [ spent my day thumbing through pictures and writing down the numbers name Songhees appeared. Given the similarity of the sounds of of cool photos I wished to purchase. It didn't take too long to some of these names to Sami sh and Saanich, l would be more cau see that I could never personally afford even the numbers I had tious as to whom is being referred. The oldest journal reference written down at that point. [ was struck by the number of quite indicating tribal territory in this area is the Galiano expedi tion excellent photos in the collection, which had not been published (Wagner 1933). From June 5th to June 9th 1792, contact was to my knowledge. I compared this with the few photos that seem maintained with Tetacus, a Makah tyee who accompanied the to be published again and again. Well, Grant Keddie has had expedi tion to his "seed gathering" village at Esquimalt Harbour. access to this intriguing collection, with modern high-resolution At this time, Victoria may have been in Makah territory or at least scanning equipment, and has prepared this edited collecti on fo r high-ranking marriage alliances gave them access to the camus our v1ewmg. -

Travel Green, Travel Locally Family Chartering

S WaS TERWaYS Natural History Coastal Adventures SPRING 2010 You select Travel Green, Travel Locally your adventure People travel across the world to experience different cultures, landscapes and learning. Yet, right here in North America we have ancient civilizations, But let nature untouched wilderness and wildlife like you never thought possible. Right here in our own backyard? select your Yes! It requires leaving the “highway” and taking a sense of exploration. But the reward is worth it, the highlights sense of adventure tangible. Bluewater explores coastal wilderness regions only The following moments accessible by boat. Our guided adventures can give await a lucky few… which you weeks worth of experiences in only 7-9 days. Randy Burke moments do you want? Learn about exotic creatures and fascinating art. Live Silently watching a female grizzly bear from kayaks in the your values and make your holidays green. Join us Great Bear Rainforest. • Witness bubble-net feeding whales in (and find out what all the fuss is about). It is Southeast Alaska simple… just contact us for available trip dates and Bluewater Adventures is proud to present small group, • Spend a quiet moment book your Bluewater Adventure. We are looking carbon neutral trips for people looking for a different in SGang Gwaay with forward to seeing you at that small local airport… type of “cruise” since 1974. the ancient spirits and totems • See a white Spirit bear in the Great Bear Family Chartering Rainforest “Once upon a time… in late July of 2009, 13 experiences of the trip and • Stand inside a coastal members of a very diverse and far flung family flew savoring our family. -

Rural Economic Development

NARA | GOAL THREE August 2011 - March 2013 Cumulative Report RURAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Northwest Advance Renewables Alliance NARA is led by Washington State University and supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2011-68005-30416 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Goal Three: Rural Economic Development: Enhance and sustain rural economic development Summary Sustainability is the crucial attribute necessary for the emerging biofuels industry to develop our rural economy. The NARA project is assessing sustainability of this emerging industry using a triple bottom line approach of assessing economic viability (techno-economic analysis – TEA), environmental impact (life cycle analysis – LCA), and social impact (community impact analysis – CIA). In addition to developing these three primary analytical tools, additional primary data is being collected. These data include social and market data through the Environmentally Preferred Products (EPP) team and environmental data through the Sustainable Production Team. The following efforts within the Systems Metrics program are integrated to provide a sustainability analysis of the project: The Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) Team assesses the overall economics of the biofuels production process from feedstock delivered to the mill gate through to biojet sale. This analysis includes the overall production mass and energy balance as well as the value needs for co-products. The TEA models the capital requirement plus the variable and fixed operating costs for producing biojet from forest residuals using our chosen pathways. The Life Cycle Assessments (LCA) and Community Impact Team assesses the environmental impact of producing aviation biofuels with our chosen pathway and compares it to the petroleum products for which it will substitute. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Res Extra Commercium and the Barriers Faced When Seeking the Repatriation and Return of Potent Cultural Objects

American Indian Law Journal Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 5 May 2017 Res Extra Commercium and the Barriers Faced When Seeking the Repatriation and Return of Potent Cultural Objects Sara Gwendolyn Ross Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj Part of the Cultural Heritage Law Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Ross, Sara Gwendolyn (2017) "Res Extra Commercium and the Barriers Faced When Seeking the Repatriation and Return of Potent Cultural Objects," American Indian Law Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj/vol4/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Journal by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Res Extra Commercium and the Barriers Faced When Seeking the Repatriation and Return of Potent Cultural Objects Cover Page Footnote Sara Ross is a Ph.D. Candidate and Joseph-Armand Bombardier CGS Doctoral Scholar at Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto, Canada. Sara holds five previous degrees, including a B.A. in French Language and Literature from the University of Alberta; B.A. Honours in Anthropology from McGill; both a civil law degree (B.C.L.) and common law degree (L.L.B.) from the McGill Faculty of Law; and an L.L.M, from the University of Ottawa. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

The Corporation of the Village of Alert

THE CORPORATION OF THE VILLAGE OF ALERT BAY 15 Maple Road- Bag Service 2800, Alert Bay, British Columbia V0N 1A0 TEL: (250)974-5213 FAX: (250) 974-5470 Email: [email protected] Web: www.alertbay.ca REGULAR MEETING OF COUNCIL AGENDA MONDAY OCTOBER 24, 2016 AT 7:00 PM IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS OF THE MUNICIPAL HALL 1. CALL TO ORDER: 2. ADOPTION OF AGENDA: 3. INTRODUCTION OF LATE ITEMS: 4. DELEGATIONS/PETITIONS/PRESENTATIONS: a) CHERYL AND ART FARQUHARSON – VARIANCE REQUEST 5. ADOPTION OF MINUTES: a) MINUTES OF THE REGULAR MEETING OF SEPTEMBER 12, 2016 b) MINUTES OF THE REGULAR MEETING OF SEPTEMBER 26, 2016 6. OLD BUSINESS AND BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES: 7. CORRESPONDENCE FOR INFORMATION: a) VISITOR CENTRE NETWORK STATISTICS SEPTEMBER 2016 b) AMBULANCE SERVICE IMPACT ON COMMUNITY 8. CORRESPONDENCE FOR ACTION: 9. NEW BUSINESS: a) REQUEST FOR DECISION – COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER PRINTING COSTS b) REQUEST FOR DECISION – FIRE HALL SOLAR INSTALLATION 10. STAFF REPORTS: a) ADMINISTRATION AND PUBLIC WORKS REPORT 11. BYLAWS/POLICIES: 12. COUNCIL REPORTS: 13. QUESTION PERIOD: 14. NEXT SCHEDULED MEETING DATE: NOVEMBER 14, 2016 15. ADJOURNMENT: THE CORPORATION OF THE VILLAGE OF ALERT BAY V/J % Bag Service 2800, Alert Bay, British Columbia VON 1A0 TEL: (250) 974-5213 FAX: (250) 974-5470 RT BAY nan:ALEornlc xumxwmu DELEGATIONREQUESTFORM Name of erson or gro up ishing to appear: Ciel?!Ezrgyaffo/1 Subje (Refpresentation : W farm/6 Purpose of presentation information only requesting a policy change her (provide details) Contact pe rson (if different than above): Telephone s’i(n«2AL,¢ EmailAddress: e Will you be providing supporting documentation? :iYes No If yes: handouts at meeting publication in agenda (must be received by 5:00pm the Thursday prior to the ‘ meeting Technical requirements: Please indicate the items you will require for your presentation. -

We Are the Wuikinuxv Nation

WE ARE THE WUIKINUXV NATION WE ARE THE WUIKINUXV NATION A collaboration with the Wuikinuxv Nation. Written and produced by Pam Brown, MOA Curator, Pacific Northwest, 2011. 1 We Are The Wuikinuxv Nation UBC Museum of Anthropology Pacific Northwest sourcebook series Copyright © Wuikinuxv Nation UBC Museum of Anthropology, 2011 University of British Columbia 6393 N.W. Marine Drive Vancouver, B.C. V6T 1Z2 www.moa.ubc.ca All Rights Reserved A collaboration with the Wuikinuxv Nation, 2011. Written and produced by Pam Brown, Curator, Pacific Northwest, Designed by Vanessa Kroeker Front cover photographs, clockwise from top left: The House of Nuakawa, Big House opening, 2006. Photo: George Johnson. Percy Walkus, Wuikinuxv Elder, traditional fisheries scientist and innovator. Photo: Ted Walkus. Hereditary Chief Jack Johnson. Photo: Harry Hawthorn fonds, Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology. Wuikinuxv woman preparing salmon. Photo: C. MacKay, 1952, #2005.001.162, Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology. Stringing eulachons. (Young boy at right has been identified as Norman Johnson.) Photo: C. MacKay, 1952, #2005.001.165, Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology. Back cover photograph: Set of four Hàmac! a masks, collection of Peter Chamberlain and Lila Walkus. Photo: C. MacKay, 1952, #2005.001.166, Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology. MOA programs are supported by visitors, volunteer associates, members, and donors; Canada Foundation for Innovation; Canada Council for the Arts; Department of Canadian Heritage Young Canada Works; BC Arts Council; Province of British Columbia; Aboriginal Career Community Employment Services Society; The Audain Foundation for the Visual Arts; Michael O’Brian Family Foundation; Vancouver Foundation; Consulat General de Vancouver; and the TD Bank Financial Group. -

MARINE BIRD SURVEYS in QC STRAIT-Final

MARINE BIRD SURVEYS IN QUEEN CHARLOTTE STRAIT AND ADJACENT CHANNELS, AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2020 December 2020 2 MARINE BIRD SURVEYS IN QUEEN CHARLOTTE STRAIT AND ADJACENT CHANNELS, AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2020 Anthony Gaston, Mark Maftei, Sonya Pastran, Ken Wright, Graham Sorenson, Iwan Lewylle Cite as: Gaston AJ, M Maftei, S Pastran, K Wright, G Sorenson and I Lewylle. 2020. MARINE BIRD SURVEYS IN QUEEN CHARLOTTE STRAIT AND ADJACENT CHANNELS, AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2020. Raincoast Education Society, Tofino, BC. 3 1084 Pacific Rim Highway, Tofino, BC (https://raincoasteducation.org/) 4 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Methods Field methods 10 Analysis 13 Results Distribution by zones 16 Total numbers of birds present 17 Timing of arrival/migration Sea ducks 18 Phalaropes 18 Auks 20 Gulls 20 Loons 21 Grebes 22 Petrels 23 Cormorants 23 Comparison with other studies 24 Marine Mammals 26 Discussion Total numbers of birds 28 Timing of arrival/migration 29 Summary 29 Acknowledgements 31 References 32 Appendices 35 5 6 INTRODUCTION Queen Charlotte Strait, a funnel-shaped passage extending ESE from the open waters of Queen Charlotte Sound, separates northern Vancouver Island from the mainland of British Columbia. It is connected, via Johnstone Strait, Discovery Passage and associated channels, with the more or less enclosed waters of the Salish Sea (Figure 1). Anecdotal information from eBird lists suggests that this area supports a high diversity of marine birds in winter and during the periods of northward and southward migration (https://ebird.org/canada/ accessed 7 November 2020; hereafter “eBird”). In addition, this area is important for marine mammals, being used regularly by the Northern Resident Orca stock, and by Humpback and Minke Whales, Dall’s and Harbour Porpoises and Pacific White-sided Dolphins, and supporting several permanent haul-outs of Steller’s Sea Lions (Ford 2014). -

2007/08 Human and Social Services Grant Recipients (PDF)

Gaming Policy and Enforcement Branch 2007/08 Direct Access Grants - Human and Social Services City Organization Name Payment Amount 100 Mile House 100 Mile House Food Bank Society $ 40,000.00 100 Mile House Cariboo Family Enrichment Centre Society 22,146.00 100 Mile House Educo Adventure School 22,740.00 100 Mile House Rocky Mountain Cadets #2887 - Horse Lake Training Centre 7,500.00 100 Mile House South Cariboo SAFER Communities Society 136,645.00 Abbotsford Abbotsford Community Services 25,000.00 Abbotsford Abbotsford Hospice Society 73,500.00 Abbotsford Abbotsford Learning Plus Society 16,000.00 Abbotsford Abbotsford Restorative Justice & Advocacy Association 28,500.00 Abbotsford Abbotsford Youth Commission 63,100.00 Abbotsford BC Schizophrenia Society - Abbotsford Branch 36,000.00 Abbotsford Fraser Valley Youth Society 5,000.00 Abbotsford Hand In Hand Child Care Society 75,000.00 Abbotsford John MacLure Community School Society 18,500.00 Abbotsford Jubillee Hall Community Club 20,000.00 Abbotsford Kinsmen Club of Abbotsford 7,000.00 Abbotsford L.I.F.E. Recovery Association 30,000.00 Abbotsford PacificSport Regional Sport Centre - Fraser Valley 50,000.00 Abbotsford Psalm 23 Transition Society 20,000.00 Abbotsford Scouts Canada-2nd Abbotsford 6,900.00 Abbotsford St. John Society-Abbotsford Branch 10,000.00 Abbotsford The Center for Epilepsy and Seizure Education BC 174,000.00 Abbotsford Upper Fraser Valley Neurological Society 28,500.00 Agassiz Agassiz Harrison Community Services 44,000.00 Aldergrove Aldergrove Lions Seniors Housing