Agenda for Czech Foreign Policy 2014.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

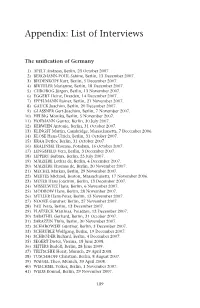

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

The Czech Foreign Policy in the Asia Pacific

CHAPTER 11 Chapter 11 The Czech Foreign Policy in the Asia Pacific IMPROVING BALANCE, MOSTLY UNFULFILLED POTENTIAL Rudolf Fürst, Alica Kizeková, David Kožíšek Executive Summary: The Czech relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC, hereinafter referred to as China) have again generated more interest than ties with other Asian nations in the Asia Pacific in 2017. A disagreement on the Czech-China agenda dominated the political and media debate, while more so- phisticated discussions about the engagement with China were still missing. In contrast, the bilateral relations with the Republic of Korea (ROK) and Japan did not represent a polarising topic in the Czech public discourse and thus remained largely unpoliticised due to the lack of interest and indifference of the public re- garding these relations. Otherwise, the Czech policies with other Asian states in selected regions revealed balanced attitudes with both proactive and reactive agendas in negotiating free trade agreements, or further promoting good relations and co-operation in trade, culture, health, environment, science, academia, tour- ism, human rights and/or defence. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT In 2017, the Czech foreign policy towards the Asia Pacific1 derived from the Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Czech Republic,2 which referred to the region as signifi- cant due to the economic opportunities it offered. It also stated that it was one of the key regions of the world due to its increased economic, political and security-related importance. Apart from the listed priority countries – China, Japan, and South Korea, as well as India – the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the re- gion of Central Asia are also mentioned as noteworthy in this government document. -

1 the Establishment in Short Succession of a Series of Non

1 The establishment in short succession of a series of non-partisan caretaker governments in European democracies such as Greece and Italy in 2010-2012 sparked a new wave of academic interest in short-term technocratic administrations, which seem to be recurring phenomenon. Different streams in the emerging literature have considered how technocratic or technocrat-led governments can best be defined and typologised; why and how they formed; and if and how their occurrence is part of a broader malaise of democracy in Europe.1 However, although such governments have sometimes been long-lasting and the default assumption often that they are or should be seen as illegitimate and democratically dysfunctional, there has thus been little consideration of if and how they legitimate themselves to mass publics. This question is particularly acute given that empirically caretaker technocrat-led administrations have been clustered in newer, more crisis-prone democracies of Southern and Eastern Europe where weaker bureaucratic traditions and high levels of state exploitation by political parties suggest a weak basis for any government claiming technocratic impartiality. In this paper, using Michael Saward’s framework of democratic politics as the making of ‘representative claims’, I re-examine the case of one of Europe’s longer-lasting and most popular technocratic administrations, the 2009-10 Fischer government in the Czech Republic to consider how a technocratic government in a newer European democracy can make seemingly successful claims to legitimacy despite unfavourable background conditions. The paper is structured as follows. It first notes how discussion of technocratic governments, has largely taken place through – and been overshadowed by - the literature on democratic party government. -

Sub-Saharan Africa in Czech Foreign Policy

CHAPTER 15 Chapter 15 Sub-Saharan Africa in Czech Foreign Policy Ondřej Horký-Hlucháň and Kateřina Rudincová FROM AN INTEREST IN AFRICA TO INTERESTS IN AFRICA?1 Back to Africa, but too late. This was the conclusion of the chapter devoted to Czech foreign policy towards Sub-Saharan Africa in the Yearbook of Czech Foreign Policy of the Institute of International Relations in 2012.2 Last year’s yearbook asserted that Czech foreign policy – in spite of budgetary austerity measures – had bounced off the bottom and attempted a “return to Africa”, which was, however, coming with a con- siderable delay. In 2013, this trend continued, characterized by the effort to deepen relations with traditional African partners, establish new relations or re-establish re- lations that had been put on ice. This effort was manifested in a 7% growth of Czech exports to the region. In a situation when the economic recession is still being felt in Europe, while Africa is experiencing record levels of economic growth, the awareness of the importance and possibilities of the African economy is growing faster than the crisis-struck foreign-policy tools of the Czech Republic may react. Most importantly, however, this interest in Africa is beginning to be felt by wider segments of Czech so- ciety, not merely the foreign policy actors, but gradually also foreign policy makers. It affects not only the media, but also the very companies that are seeking to expand their markets. The imported, but largely well-founded “Africa on the rise” fashion was, for example, also reflected in the employment of the term Emerging Africa in the names of both of the large and abundantly attended events organized by the MFA in 2013 on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Pan-African organization on the opportunities for Czech business on the African continent. -

Caretaker Governments in Czech Politics: What to Do About a Government Crisis

Europe-Asia Studies ISSN: 0966-8136 (Print) 1465-3427 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ceas20 Caretaker Governments in Czech Politics: What to Do about a Government Crisis Vít Hloušek & Lubomír Kopeček To cite this article: Vít Hloušek & Lubomír Kopeček (2014) Caretaker Governments in Czech Politics: What to Do about a Government Crisis, Europe-Asia Studies, 66:8, 1323-1349, DOI: 10.1080/09668136.2014.941700 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2014.941700 Published online: 17 Sep 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 130 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ceas20 Download by: [Masarykova Univerzita v Brne] Date: 20 February 2017, At: 05:13 EUROPE-ASIA STUDIES Vol. 66, No. 8, October 2014, 1323–1349 Caretaker Governments in Czech Politics: What to Do about a Government Crisis VI´T HLOUSˇEK & LUBOMI´R KOPECˇ EK Abstract Czech politics suffers from a low durability of most of its governments, and frequent government crises. One of the products of this situation has been the phenomenon of caretaker governments. This article analyses why political elites have resorted to this solution, and discusses how this has reflected an older Czech tradition. Two cases of such governments are analysed in detail. The Tosˇovsky´ government was characterised by the ability of the Czech president to advance his agenda through this government at a time when the party elites were divided. The Fischer government was characterised by the considerably higher role of parties that shaped and limited the agenda of the cabinet, and the president played a more static role. -

India - Czech Republic Relations

India - Czech Republic Relations Relations between India and Czech Republic are deep rooted. According to Czech Indologist, Miloslav Krasa, "if not earlier, then surely as early as the 9th and 10th Centuries A.D., there existed both land and maritime trade routes from Asian markets to Czech lands, along which precious goods from the East, including rare Indian spices, reached this country". Relations between the two countries continued to strengthen in coming centuries with frequent exchange of visits by academicians, artists, businessmen and political leaders. By making the knowledge of India available and accessible, the scholars in the Czech Republic are continuing the long tradition of the founders of Czech Indology, dating back to the period before and particularly after the creation of independent Czechoslovakia in 1918.The comprehensive process of learning about India and of establishing contacts between Czechoslovakia and India was facilitated and accelerated by frequent visits of prominent Indian scholars, journalists, politicians and artists in Prague and other cities of Czechoslovakia. The increase in bilateral trade created even more possibilities for establishing interpersonal contacts, especially after the Czechoslovak Consulate was opened in Bombay in 1920 and later in Calcutta. Thus, a way opened for a group of people, joined not only by professional interests, but also mutual sympathies and friendships, to come together. India’s relations with the former Czechoslovakia, and with the Czech Republic, have always been warm and friendly. Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore visited Czechoslovakia in 1921 and 1926. A bust of Tagore is installed in an exclusive residential area in Prague named after Tagore. The Indian leader, who visited Czechoslovakia the most times between 1933 and1938 was Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. -

Důvěru Členům Vlády Projevuje Polovina Občanů. to Je Na České Poměry Hodnota Velmi Vysoká

INFORMACE Z VÝZKUMU STEM TRENDY 2/2010 VYDÁNO DNE 9.3.2010 ČLENŮM VLÁDY ČR DŮVĚŘUJE POLOVINA OBČANŮ, PREMIÉRA CHVÁLÍ SKORO VŠICHNI. Důvěru členům vlády projevuje polovina občanů. To je na české poměry hodnota velmi vysoká. Úřednický kabinet se těší podpoře spíše pravicově orientovaných občanů a jeho kredit nepochybně souvisí s velmi příznivým hodnocením několika klíčových ministrů. Naprosto mimořádné je postavení premiéra Jana Fischera (89 % kladných hodnocení), příznivá hodnocení zřetelně převažují i u dalších známých a výrazných ministrů vlády (Eduard Janota, Martin Pecina, Jan Kohout, Daniela Kovářová). Citované výsledky pocházejí z výzkumu STEM provedeného na reprezentativním souboru obyvatel České republiky starších 18 let, který se uskutečnil ve dnech 15.–22. 2. 2010. Respondenti byli vybíráni metodou kvótního výběru. Na otázky odpovídal rozsáhlý soubor 1240 respondentů. V září loňského roku důvěřovalo členům vlády 44 % procent lidí a v současnosti se tento podíl zvýšil přesně na polovinu. To je hodnota v dějinách českých vlád nebývalá. "Důvěřujete následujícím institucím? – Členové vlády ČR." Určitě ne Určitě ano 14% 7% Spíše ano Spíše ne 43% 36% Pramen: STEM, Trendy 2/2010, 1240 respondentů starších 18 let V třináctiletém období, kdy STEM sleduje důvěru v českou vládu, se těšila vůbec nejvyšší důvěře vláda Vladimíra Špidly, a to krátce po svém nástupu v listopadu 2002 (55 %). Důvěra v členy Špidlova kabinetu vydržela však jen několik měsíců, během dalšího půl roku následoval pád na obvyklou úroveň pod 40 %. "Důvěřujete následujícím institucím? - Členové / Ministři vlády ČR." (podíly odpovědí určitě ano + spíše ano) 60 55 % 50 50 44 44 39 37 37 40 35 35 41 36 37 31 31 29 30 33 34 30 24 24 20 21 10 04 04 11 02 10 02 10 05 11 05 10 02 02 05 05 10 02 10 02 09 02 7/ 9/ 9/ 0/ 0/ 1/ 1/ 2/ 2/ 3/ 3/ 4/ 5/ 6/ 7/ 7/ 8/ 8/ 9/ 9/ 0/ 9 9 9 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Pramen: STEM, Trendy 1997-2010 Pro Fischerovu vládu platí, že má pověst vlády spíše pravicové. -

Czech–Liechtenstein Relations Past and Present

1 Peter Geiger – Tomáš Knoz – Eliška Fučíková – Ondřej Horák – Catherine Horel – Johann Kräftner – Thomas Winkelbauer – Jan Županič CZECH–LIECHTENSTEIN RELATIONS PAST AND PRESENT A summary report by the Czech-Liechtenstein Commission of Historians Brno 2014 2 CONTENTS A Word of Introduction Foreword I. Introduction a. The Czech-Liechtenstein Commission of Historians and its activities 2010–2013 b. Sources, literature, research, methodology II. The Liechtensteins in times of change a. The Middle Ages and the Early Modern Age b. The 19th Century c. The 20th Century III. Main issues a. Sites of memory and constructing a historical image of the Liechtensteins b. The Liechtensteins and art c. Land reform and confiscation IV. Conclusions a. Summary b. Outstanding areas and other possible steps V. Prospects VI. A selection from the sources and bibliography a. Archival sources b. Source editions c. Bibliography VII. Workshops and publications by the Commission of Historians a. Workshops b. Publications by the Czech-Liechtenstein Commission of Historians Summary Zusammenfassung Index 3 A Word of Introduction This joint summary report by the Czech-Liechtenstein Commission of Historians represents an important milestone in the relations between both of our countries. On the one hand, the Commission of Historians examined the joint history of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, as well as the House of Liechtenstein, while on the other, they looked at the relations between both our countries in the 20th century. The commission's findings have contributed greatly towards better mutual understanding and have created a valuable basis for the continued cooperation between the two countries. The depth and thoroughness of this three-year work by the Commission of Historians is impressive, and this extensive publication sheds light on the remarkable and still visible mark that the House of Liechtenstein left behind on Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia. -

General Elections in the Czech Republic 28Th and 29Th May 2010

CZECH REPUBLIC European Elections monitor General Elections in the Czech Republic 28th and 29th May 2010 ANALYSIS On 5th February Czech President Vaclav Klaus announced that the next general elections would 1 month before take place on 28th and 29th May 2010. 5,053 candidates, one quarter of whom are women, the poll representing 27 parties are standing (ie +1 in comparison with the previous general election on 2nd and 3rd June 2006), 15 only are present in country’s 14 regions (22 in Prague). The general elections are vital for the two ‘main’ political parties – the Civic Democratic Party (ODS) and the Social Democratic Party (CSSD) – and the same goes for their leaders, Petr Necas (who replaces Mirek Topolanek) and Jiri Paroubek. «2010 will be of major importance because the general election, and later on the senatorial elections will also decide on the repre- sentation of the parties before the presidential election in 2013,» indicates political expert Petr Just. Indeed one third of the Czech Upper Chamber will be renewed next autumn. The Czech Political System - The Social Democratic Party (CSSD), led by former The Czech Parliament is bicameral comprising the Prime Minister Jiri Paroubek, has 74 seats; Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. The latter com- - The Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia prises 81 members elected for six years on a single (KSCM) – The heir of the Communist Party of the So- majority list in two rounds and which is renewable by cialist Republic of Czechoslovakia and the last non- thirds. The choice of this mode of election matches the reformed Communist party in Central Europe is led by will of those who wrote the Constitution, and notably Vojtech Filip – has 26 MPs; that of former President of the Republic (1993-2003), - The Christian Democratic Union-People’s Party (KDU- Vaclav Havel, who wanted to facilitate the election of CSL), which lies to the right on the political scale is led independent personalities who were firmly established by Cyril Svoboda, with 13 seats; within the constituencies. -

China's Sticks and Carrots in Central Europe: the Logic and Power Of

POLICY PAPER China’s Sticks and Carrots in Central Europe: The Logic and Power of Chinese Influence IVANA KARÁSKOVÁ, ALICJA BACHULSKA, BARBARA KELEMEN, TAMÁS MATURA, FILIP ŠEBOK, MATEJ ŠIMALČÍK POLICY PAPER China’s Sticks and Carrots in Central Europe: The Logic and Power of Chinese Influence IVANA KARÁSKOVÁ, ALICJA BACHULSKA, BARBARA KELEMEN, TAMÁS MATURA, FILIP ŠEBOK, MATEJ ŠIMALČÍK CHINA’S STICKS AND CARROTS IN CENTRAL EUROPE: THE LOGIC AND POWER OF CHINESE INFLUENCE Policy paper June 2020 Editor – Ivana Karásková Authors – Alicja Bachulska, Ivana Karásková, Barbara Kelemen, Tamás Matura, Filip Šebok, Matej Šimalčík Citation – Karásková, I. et al. (2020). China’s Sticks and Carrots in Central Europe: The Logic and Power of Chinese Influence. Prague, Czech Republic, Association for International Affairs (AMO). Handbook for stakeholders – To access the handbook for stakeholders stemming from this report, please refer to the electronic version which can be found online at www.mapinfluence.eu. The publication was prepared within the project MapInfluenCE (previously known as ChinfluenCE), that maps China’s influence in Central Europe, specifically Czechia, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia. The project is designed and run by the Association for International Affairs (AMO), a Prague-based foreign policy think tank and NGO. The preparation of this paper was supported by a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Typesetting – Zdeňka Plocrová Print – Vydavatelství KUFR, s.r.o. – tiskárna ASSOCIATION FOR INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS (AMO) -

1/2009 ARMED FORCES ARMED REVIEW Visit in Kosovo

REP H UB EC L Z IC C FOREIGN OPERATIONS – THE KEY TO SECURITY 1/2009 ARMED FORCES ARMED REVIEW Visit in Kosovo The Prime Minister of the Czech Republic, H.E. Jan Fischer, visited Czech troops in Kosovo on August 19th, 2009. The Prime Minister was accompanied by Vice-Premier and Minister of Defence, H.E. Martin Barták. Apart from visiting Czech deployment at Camp Sajkovac, Prime Minister Fischer and Minister Barták had a meeting with Commander KFOR, Lieutenant-General Giuseppe E. Gay, the President of the Republic of Kosovo, H.E. Fatmir Seidiu, and the Prime Minister, H.E. Hashim Thaci. Since NATO is considering progressive downsizing of KFOR’s force posture, Prime Minister Fischer and Defence Minister Barták were particularly interested in the current security situation. “The transformation of KFOR and reduction of deployed Allied forces is contingent on a positive development of security situation in Kosovo. The Czech Republic again plans to assign a sizeable contingent next year. The number of Czech service personnel in Kosovo in the years ahead depends on the course of action taken by NATO“, said Minister Barták. At present, a Czech Armed Forces contingent with authorised strength of 550 personnel operates as a part of KFOR. The 15th contingent’s core comprises the members of the 131st Artillery Battalion the 13th Artillery Brigade based in Pardubice. The members of the 14th Logistic Support Brigade Pardubice also form a large part of the force. In addition to that, the contingent includes soldiers from 54 units and components of the Armed Forces of the Czech Republic according to required occupational specialties. -

Long-Range Ballistic Missile Defense in Europe

Long-Range Ballistic Missile Defense in Europe Updated April 26, 2010 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL34051 Long-Range Ballistic Missile Defense in Europe Summary In early 2007, after several years of internal discussions and consultations with Poland and the Czech Republic, the Bush Administration formally proposed to defend against an Iranian missile threat by deploying a ground-based mid-course defense (GMD) element in Europe as part of the global U.S. BMDS (Ballistic Missile Defense System). The system would have included 10 interceptors in Poland, a radar in the Czech Republic, and another radar that would have been deployed in a country closer to Iran, to be completed by 2013 at a reported cost of at least $4 billion. The proposed European BMD capability raised a number of foreign policy challenges in Europe and with Russia. The United States negotiated and signed agreements with Poland and the Czech Republic, but for a number of reasons those agreements were not ratified by the end of the Bush Administration. On September 17, 2009, the Obama Administration announced it would cancel the Bush- proposed European BMD program. Instead, Defense Secretary Gates announced U.S. plans to develop and deploy a regional BMD capability in Europe that could be surged on relatively short notice during crises or as the situation may demand. Gates argued this new capability in the near- term would be based on expanding existing BMD sensors and interceptors. Gates argued this new Phased Adaptive Approach (PAA) would be more responsive and adaptable to the pace and direction of Iranian short- and medium-range ballistic missile proliferation.