National Web Studies: Mapping Iran Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of God

In The Name Of God Heidarali Korangi Father's Name: Abbas ID number: 1210 Birthdate: 1970 December 3 National Code: 1287952917 Mobile: 09121138859 Phone: (+98) 21 86037407 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Educational background: Ph.D. student in Business Intelligence at Islamic Azad University, Najafabad Branch, 2016 MSc in Information Technology from Islamic Azad University, Prof. Hassabi Tafresh Branch, 2016 GPA 46/19 Bachelor of Computer Engineering Software Aberdeen Virtual College US 2008 GPA 18/50 Positions: Executive secretary of specialized scientific network seminars Designer of four-choice software security lesson questions at Tehran Office of Education and Research, 2013 ، Teaching some short -term courses such as ”E-Organization ، E-Government ، E-Commerce ، E-Learning ”ECSA ، OWASP ،CHFI ،ISMS ، CEH & Network and Information Security Postgraduate research student in 2015 at Prof. Hassabi Tafresh Islamic Azad University PhD elected student in Information Technology in Islamic Azad University of Najafabad , Iran, with a grade point average of 19/33 Jobs: Vice President of Advanced Technology Complex Shahid-Alamol-Hoda. Head of Information Security Department of West Asia Scientific Network CEO Of a Knowledge-Based corporation called Tosun Information Technology Strategists Specialties: Linux-Java-JEE—Postgre SQL-MySQL-Spring- Hibernate-CEH-ECSA-ISMS-OWASP- CHFI- Maven-CREST-PHP-C#.Net-CCNA-CCNP-PWK-SharePoint Server and etc. Past Careers: Member of the Board of Directors of Pasteur Company -

Mapping Iran Online

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Center for Global Communication Studies Iran Media Program (CGCS) 2-2012 National Web Studies: Mapping Iran Online Richard Rogers Esther Weltevrede Sabine Niederer Erik Borra Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/iranmediaprogram Part of the Communication Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rogers, Richard; Weltevrede, Esther; Niederer, Sabine; and Borra, Erik. (2012). National Web Studies: Mapping Iran Online. Iran Media Program. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/iranmediaprogram/2 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/iranmediaprogram/2 For more information, please contact [email protected]. National Web Studies: Mapping Iran Online Abstract This work offers an approach to conceptualizing, demarcating and analyzing a national web. Instead of defining a priori the types of websites to be included in a national web, the approach put forward here makes use of web devices (platforms and engines) that purport to provide (ranked) lists of URLs relevant to a particular country. Once gathered in such a manner, the websites are studied for their properties, following certain of the common measures (such as responsiveness and page age), and repurposing them to speak in terms of the health of a national web: Are sites lively, or neglected? The case study in question is Iran, which is special for the degree of Internet censorship undertaken by the state. Despite the widespread censorship, we have found a highly responsive Iranian web. We also report on the relationship between blockage, responsiveness and freshness, i.e., whether blocked sites are still up, and also whether they have been recently updated. -

Stand Number/ ﻧﺎم ﺷﺮﮐﺖ ﺳﺎﻟﻦ /Company Name Hall Number ﺷﻤﺎره ﻏﺮﻓﻪ

Stand Number/ ﻧﺎم ﺷﺮﮐﺖ ﺳﺎﻟﻦ /Company Name Hall Number ﺷﻤﺎره ﻏﺮﻓﻪ ﺳﺎﻟﻦ Hall 5 5 CHINA - PAVILION 5 5 CHINA - PAVILION ACE Marketing 5.2.4 5 ACE Marketing B&C Fiber Technology 5.2.19 5 B&C Fiber Technology Beijing Huahuan Electronics Co., Ltd. 5.1.51 5 Beijing Huahuan Electronics Co., Ltd. Beijing HuaXing Cutting-edge Technology Development Co., Ltd. 5.1.48 5 Beijing HuaXing Cutting-edge Technology Development Co., Ltd. Beijing Telesea Technologies Development Co., Ltd. 5.1.16 5 Beijing Telesea Technologies Development Co., Ltd. Deviser Electronics Instrument Co., Ltd. 5.2.8 5 Deviser Electronics Instrument Co., Ltd. Fasten Group 5.2.23 5 Fasten Group Hangzhou Putianle Cable Co., Ltd. 5.1.21 5 Hangzhou Putianle Cable Co., Ltd. Jiangsu Changyue Trading Co., Ltd. 5.1.45 5 Jiangsu Changyue Trading Co., Ltd. Jiangsu Diyi Group Co., Ltd 5.1.49 5 Jiangsu Diyi Group Co., Ltd Jiangsu Hengxin Technology Co. 5.1.56 5 Jiangsu Hengxin Technology Co. Kingsignal Technology Co., Ltd. 5.2.21 5 Kingsignal Technology Co., Ltd. Lanbowan Technology Co. Ltd. 5.1.17 5 Lanbowan Technology Co. Ltd. Mobi Antenna Technologies (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd. 5.1.27 5 Mobi Antenna Technologies (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd. Nanjing Hedot Network Technology Co., Ltd. 5.1.18 5 Nanjing Hedot Network Technology Co., Ltd. Nanjing Huamai Technology Co., Ltd. 5.1.52 5 Nanjing Huamai Technology Co., Ltd. Ningbo Longtu Network Technology Co., Ltd. 5.1.15 5 Ningbo Longtu Network Technology Co., Ltd. NINGBO LONGXING TELECOMMUNICATIONS EQUIPMENT MANUFACTURING NINGBO LONGXING TELECOMMUNICATIONS EQUIPMENT MANUFACTURING 5.2.22 5 CO.,LTD. -

22. 0.3. 200 S- Kurzfassung Der Dissertation

Die approbierte Originalversion dieser Dissertation ist an der Hauptbibliothek der Technischen Universität Wien aufgestellt (http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at). The approved original version of this thesis is available at the main library of the Vienna University of Technology (http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at/englweb/). DISSERTATION Auswirkungen moderner Technologien auf die kulturelle Entwicklung der iranischen Gesellschaft Ausgeführt zum Zwecke der Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der technischen Wissenschaften unter der Leitung von Univ. Professor Dr. phil. Wolfgang Hofkirchner E187 Institut für. Gestaltungs- und Wirkungsforschung eingereicht an der Technischen Universität Wien Fakultät für Technische Naturwissenschaften und Informatik .e von Dip!.- Ing. Seyed-Mohsen Ekssir-Monfared i 8026512 Brigittenauer Lände 156 - 158 / 6 /20, 1200 - Wien \ I Wien, am 22. 0.3. 200 S- Kurzfassung der Dissertation Kurzfassung der Dissertation Der Iran, der im Laufe der Jahrtausende immer als Drehscheibe der aufeinanderprallenden verschiedenen Kulturen und Gebräuche gedient hat, erfährt einen großen sozialen und kulturellen Umbruch. Im Informationszeitalter und im Zuge des Globalisierungsprozesses, in welchem die Welt mehr denn je zusammenrückt und die Bezugnahme der Kulturen intensiver geworden ist, sind die Auswirkungen "fremder" Kulturen auf die "eigene" und umgekehrt stärker denn je. Die Welt ist in der Tat "kleiner" und "überschau barer" geworden. Allerdings: je enger die Welt zusammenrückt und die Homogenisierung und Verwestlichung, insbesondere Amerikanisierung der Kulturen durch die technologische Entwicklung und den • verbreiteten Einsatz neuer I&K-Technologien vorangetrieben wird, verstärkt sich auf der anderen Seite eine Kraft zu Dezentralismus, Inhomogenität sowie eine Tendenz zur Rückkehr zu lokalen kulturellen Werten. Auf der anderen Seite ist es der Fundamentalismus und die Rückkehr zu den Traditionen und dem religiösen Glauben, die keine Affinität mit dem Leben im 21. -

The Relationship of Supportive Roles with Mental Health and Satisfaction with Life in Female Household Heads: a Structural Equations Model

The Relationship of Supportive Roles With Mental Health and Satisfaction With Life in Female Household Heads: A Structural Equations Model Nooshin Shadabi Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, IRAN Sara Esmaelzadeh – Saeieh Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, IRAN Mostafa Qorbani Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, IRAN Touran Bahrami Babaheidari Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, IRAN Zohreh Mahmoodi ( [email protected] ) Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, IRAN Research Article Keywords: Female Household Heads, Supportive Roles, Satisfaction with Life, Mental Health, Structural Equations Posted Date: December 30th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-129599/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/15 Abstract Background: Female household heads are faced with many more problems than men due to their multiple concurrent roles. The present study was conducted to determine the relationship of supportive roles with mental health and satisfaction with life in female household heads using a structural equations model. Methods: The present descriptive-analytical study was conducted on 286 eligible female household heads in Karaj, Iran, in 2020, who were selected by convenience sampling. Data were collected using VAX social support, the perceived social support scale, the general health questionnaire (GHQ), and the satisfaction with life questionnaire plus a socio-demographic checklist, and were analyzed in SPSS-16 and Lisrel-8.8. Results: The participants’ mean age was 43.1±1.7 years. According to the path analysis results, satisfaction with life had the highest direct positive relationship with perceived social support (B=0.33) and the highest indirect positive relationship with age (B=0.13) and the highest direct and indirect positive relationship with education and social support (B=0.13). -

La Province De Teheran

LLAA PPRROOVVIINNCCEE DDEE TTEEHHEERRAANN Mai 2019 © DG Trésor Présentation La province de Téhéran, centre politique et économique de l’Iran générale Au Nord de l’Iran, localisée au pied du massif de l’Alborz dont le mont Damavand culmine à 5 671 mètres, la province de Téhéran inclut la capitale iranienne et ses Population (2016) : périphéries, à travers une organisation administrative en 16 districts. Capitale à la 13 267 367 habitants topographie contrastée, l’altitude des quartiers de Téhéran, entre 1100 et 1700 (16,6 % de la population nationale) mètres au-dessus du niveau de la mer, est bien souvent corrélée au capital économique et social des habitants1. La province bénéficie d’un climat continental Superficie : 12 981 km2 caractérisé par quatre saisons bien distinctes et par un été long et chaud. Devenue la capitale de l’Iran le 12 mars 1786 par une décision d’Agha Mohammad Khan, fondateur de la dynastie Qadjar, Téhéran est passée d’une cité d’une dizaine de milliers de résidents à une mégalopole comptant plus de 8,6 millions d’habitants. En parallèle de cette croissance démographique, le poids de la province de Téhéran dans l’économie iranienne a connu une progression continue depuis le 19ème siècle. Téhéran est le centre administratif et poumon économique du pays. Depuis fin novembre 2018, le maire de la ville est Pirouz Hanachi et depuis décembre 2018, le gouverneur de la province de Téhéran est Anoushirvan Mohseni-Bandpey (précédemment président de l’Organisation d’Etat pour la protection sociale). Plus de la moitié de la population de la province a moins de 35 ans. -

Iranian Internet Infrastructure and Policy Report

JULY 2015 Iranian Internet Infrastructure and Policy Report A Small Media monthly report bringing you all the latest news on internet policy and online censorship direct from Iran. smallmedia.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License Iranian Internet 2 Infrastructure and Policy Report Introduction Iran’s pervasive internet filtering system makes circumvention tools necessary for many run-of-the-mill online activities, such as posting a status update on Facebook or uploading a picture to Instagram. This requirement can make using the internet in Iran a persistent and frustrating challenge. Luckily for Iranian netizens, there are resources available to help them gain access to blocked sites. In what follows, we’ll examine one such resource. This month’s report looks at Filtershekanha, a mailing list which sends its subscribers biweekly updates on the latest circumvention tools and provides instructions about how to download the required software. Through a combination of an interview with the list’s founder Nariman Gharib and a presentation and discussion of circumvention tool download statistics, we’ll unpack what Filtershekanha is, how it functions, and what it might tell us about internet filtering in Iran more generally. Filtershekanha is almost certainly not the only source of information about circumvention tools in Iran, and the data we analyse is not intended to be representative of Iran’s internet-using population. Yet with nearly 100,000 subscribers, we think Filtershekanha can serve as a compelling case study that will allow us to probe questions about how Iranians access information about circumvention tools. -

Company Profile

Company Profile Grounding Systems Cathodic Protection Systems “Petweld” Exothermic Welding Equipment Lightning Protection Systems Flange Insulation kits LOB 8 Office 15 Ground Floor P.O.Box 17565, Jebel Ali, Dubai, U.A.E Tel :+(971) 4 88 11 361 Fax:+(971) 4 88 11 363 [email protected] www.petuniafze.com January, 2010 Contents: Chapter 1: President's Message 6 Chapter 2: Company Overview 10 Chapter 3: Capabilities 14 Chapter 4: Project Refrences 20 Chapter 5: Equipment Details 74 Chapter 6: Organizational Chart 80 Chapter 7: Key Personnel 84 Chapter 8: Copies of Work Order 88 Chapter 9: Quality System 102 Chapter 10: Certificates 106 Chapter 11: Customer Satisfactions 114 Chapter 12: Catalogues 122 Contents President’s Message Chapter: 1 President’s President’s Message PETUNIA Message: Dear Sir/Madam, On behalf of PETUNIA directors, Managers and Staffs, I would like to thank you for your patronage and support. PETUNIA has been developing businesses throughout the world as an enterprise that provides total solutions for Grounding Systems, Lightning and Surge Protection and Corrosion Control and Prevention. It has been established as a new company in the world of exothermic welding technology in 1991. Now after 18 years of exceeding the expectation of our customer, by aspiring to the highest level of excellence in our products and services, we are the largest organization in protection industry in the Middle East. We take great pride each day to provide the fine protection solutions. Members of PETUNIA management and administrative team are ready to give their personal attention to any of your projects. -

Iran: Tightening the Net 2020 After Blood and Shutdowns

Iran: Tightening the Net 2020 After Blood and Shutdowns. First published by ARTICLE 19, September 2020 ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA United Kingdom www.ARTICLE 19.org Text and analysis Copyright ARTICLE 19, September 2020 (Creative Commons License 3.0) Typesetting, Ana Z. ARTICLE 19 works for a world where all people everywhere can freely express themselves and actively engage in public life without fear of discrimination. We do this by working on two interlocking freedoms, which set the foundation for all our work. The Freedom to Speak concerns everyone’s right to express and disseminate opinions, ideas and information through any means, as well as to disagree from, and question power- holders. The Freedom to Know concerns the right to demand and receive information by power-holders for transparency good governance and sustainable development. When either of these freedoms comes under threat, by the failure of power-holders to adequately protect them, ARTICLE 19 speaks with one voice, through courts of law, through global and regional organisations, and through civil society wherever we are present. About Creative Commons License 3.0: This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 2.5 license. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, provided you: 1) give credit to ARTICLE 19; 2) do not use this work for commercial purposes; 3) distribute any works derived from this publication under a license identical to this one. To -

Le Nuove Vie Del Business in Iran, Emirati E Arabia Saudita

€ 2,50 febbraio-marzo 2018 INTERNATIONAL Quarta edizione DOSSIER GRANDI LAVORI Cantieri e progetti nell’oil & gas, energie GOLFO rinnovabili, trasporti, nuove città FASHION & LUXURY PERSICO E-commerce o mall? Dove crescono i consumi LE NUOVE VIE dei millenial DEL BUSINESS IN IRAN, EMIRATI POWER 100 I nomi che contano E ARABIA SAUDITA nelle relazioni in Iran e nei paesi arabi MF International, gli speciali di MF-Milano Finanza – Supplemento a Spedizione inart. A.P. 1 c. 1 L. 46/04, DCB Milano COPYRIGHT © SALINI IMPREGILO ENJOY THE PRIVILEGES WHERE BUSINESS MEETS BENEFITS To become a member and start receiving benefits of Turkish Airlines Corporate Club, please visit corporateclub.thy.com Tabellare Turkish.indd 1 06/02/18 11:00 Febbraio-Marzo 2018 I CONTENUTI INTERNATIONAL GOLFOITALIA NEWS BUSINESS Golfo Oggi Banking 6 Personaggi, idee, progetti, numeri Tre big in gara sul business tricolore che stanno segnando l’attualità 56 di Andrea Pira COVER STORY New Tech Silicon Gulf 58 di Francesco Bisozzi Power 100 I nomi dei personaggi arabi, iraniani 12 e italiani che contano nel business e nelle relazioni bilaterali per fare affari con i paesi del Golfo Il Kingdom Center a Riad, realizzato da Salini- FORUM Impregilo e terminato nel 2002, è tutt’ora uno dei luoghi-simbolo della capitale saudita Iran-Arabia Saudita, quale guerra o pace? 24 Nicola Pedde e Massimo Campanini DOSSIER GRANDI LAVORI Architettura & design si confrontano sulla possibile Meno lusso e retail, evoluzione della crisi in Medio Push strategy, così si spinge 62 il made in Italy il richiamo è la cultura Oriente che coinvolge le due grandi di Martina Mazzotti potenze regionali 42 Il finanziamento dei compratori di Martina Mazzotti esteri, con la garanzia di Sace e Fashion & Luxury l’abbattimento del tasso di interesse, Mall o e-commerce? sta creando nuove opportunità. -

Iran Telecom Market Review & Investment Opportunity Table of Contents

نشريه تخصصي كانون تفكر مخابرات ايران سال يازدهم، شماره 52 خرداد و تير 1395 Iran Telecom Market Review & Investment Opportunity Table of Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................2 IRAN AT A GLANCE ...........................................................................................................4 IRAN Economy ....................................................................................................................5 Iranian Telecom sector: History, Governance and Regulation .............................8 IRAN Mobile Market Review...........................................................................................11 Fixed Broadband Market in Iran ................................................................................... 15 IRAN FIXED MARKET DATA SHEET ........................................................................... 18 IRAN MOBILE MARKET DATA SHEET ........................................................................ 21 Revolution of Iranian Startups ....................................................................................22 MVNO Licensing in IRAN .............................................................................................. 24 Virtual Operators and Real Opportunities ............................................................. 24 Opportunities in Iranian Telecom Market ...............................................................26 How to do business in Iran successfully -

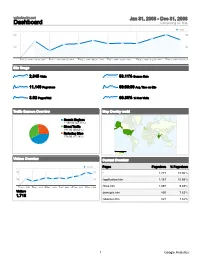

Dashboard Comparing To: Site

velocimetry.net Jan 31, 2008 - Dec 31, 2008 Dashboard Comparing to: Site Visits 400 400 200 200 Jan 31, 2008 - Jan 31, 2008 Mar 1, 2008 - Mar 31, 2008 May 1, 2008 - May 31, 2008 Jul 1, 2008 - Jul 31, 2008 Sep 1, 2008 - Sep 30, 2008 Nov 1, 2008 - Nov 30, 2008 Site Usage 2,845 Visits 53.11% Bounce Rate 11,140 Pageviews 00:03:30 Avg. Time on Site 3.92 Pages/Visit 60.39% % New Visits Traffic Sources Overview Map Overlay world Search Engines 1,198.00 (42.11%) Direct Traffic 871.00 (30.62%) Referring Sites 776.00 (27.28%) Visits 1 653 Visitors Overview Content Overview Visitors Pages Pageviews % Pageviews 300 300 / 1,773 15.92% 150 150 /application.htm 1,187 10.66% Jan 31, 2008 - Mar 1, 2008 - M May 1, 2008 - Jul 1, 2008 - Jul Sep 1, 2008 - S Nov 1, 2008 - N /links.htm 1,097 9.85% Visitors /principle.htm 850 7.63% 1,718 /aboutus.htm 827 7.42% 1 Google Analytics velocimetry.net Jan 31, 2008 - Dec 31, 2008 Traffic Sources Overview Comparing to: Site Visits 400 400 200 200 Jan 31, 2008 - Jan 31, 2008 Mar 1, 2008 - Mar 31, 2008 May 1, 2008 - May 31, 2008 Jul 1, 2008 - Jul 31, 2008 Sep 1, 2008 - Sep 30, 2008 Nov 1, 2008 - Nov 30, 2008 All traffic sources sent a total of 2,845 visits 30.62% Direct Traffic Search Engines 1,198.00 (42.11%) Direct Traffic 27.28% Referring Sites 871.00 (30.62%) Referring Sites 776.00 (27.28%) 42.11% Search Engines Top Traffic Sources Sources Visits % visits Keywords Visits % visits google (organic) 1,105 38.84% velocimetry 111 9.27% (direct) ((none)) 871 30.62% stereo piv 78 6.51% en.wikipedia.org (referral) 151 5.31%