Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TV Club Newsletter; April 4-10, 1953

COVERING THE TV BEAT: GOVERNMENT RESTRICTIONS ON COLOR TV ARE BEING LIFTED. How- ever, this doesn't bring color on your screen any closer. Color TV will arrive after extensive four-month field tests of the system recently developed through the pooled research of major set manufacturers; after the FCC studies and ap- proves the new method ; and after the many more months it will take to organize factory production of sets and to in- stall color telecasting equipment. TED MACK AND THE ORIGINAL AMATEUR HOUR RETURN to your TV screen April 25 to be seen each Saturday from 8:30 - 9 p.m. It will replace the second half of THE ALL-STAR REVUE, which goes off. WHAM-TV and WBEN-TV have indicated that they will carry the show. THREE DIMENSIONAL TV is old stuff to the Atomic Energy Commission. Since 1950, a 3D TV system, developed in coop- eration with DuMont, has been in daily use at the AEC's Argonne National Laboratories near Chicago. It allows technicians to watch atomic doings closely without danger from radiation. TV WRESTLERS ARE PACKING THEM IN AT PHILADELPHIA'S MOVIE houses where they are billed as added stage attractions with simulated TV bouts. SET-MAKERS PREDICT that by the end of the year 24-inch sets will constitute 25% of production. FOREIGN INTRIGUE is being released for European TV distri- bution with one version in French and the other with Ger- man subtitles. "I LOVE LUCY", WILL PRESENT "RICKY JR.", the most celebrat- ed TV baby, in its forthcoming series now being filmed in Hollywood. -

The Ledger and Times, April 16, 1953

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 4-16-1953 The Ledger and Times, April 16, 1953 The Ledger and Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger and Times, "The Ledger and Times, April 16, 1953" (1953). The Ledger & Times. 1272. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/1272 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. :g hi A .0.• ..•••••• Aks AWL It. 11,f5N Selected As Best All sound Kentucky Community Newspaper for 1947 We Weather Are KN^ETUCKV: Fair with -ir -- terrepersteoires-neetr -Or a little Helping To 1411NNsorst• below freezing tomeht. low 30 to 34 in the east and a Build Murray , • `1,:*"\ ‘7441"--"7- 32 to 38 in the east portion. Friday fair and continued Each Day cool. r• YOUR PROGRESSIVE HOME NEWSPAPER United Press IN ITS 74th YEAR Murray, Ky., Thursday Afternioon, April 16, 1953 MURRAY POPULATION . - - 8,000 Vol. XXIX; No. 91 Vitality Dress Shoes IKE CHALLENGES RE!)s IN PEACE MOVE Basque, Red Calf and , als; In Flight Blue Calf Soon de Hoard I Now.4)':,t7".. Lions Will Be Six Point Program Listed $10.95 By LEIO, PANMUNJOM, ,./iApril 16 Sold To Aid By President To End War Al'OUttd • / (UP)-Red trucks b. /ambulances today delivered the first of 805 By MERRIMAN SMITH ,hopes with mere words and prom- I Allied sick and wounded prisoners Health Center WASHINGTON April 16 iUPI- ises and gestures," he said. -

Howdy Doody on Radio

RADIO RECALL. June 2017, Volume 34, No. 3 HOWDY DOODY ON RADIO From 1947 to 1960, The Howdy Doody Bob Smith got his start in broadcasting on Show entertained children across the country, WBEN radio in Buffalo, NY, after being credited by historians as one of the leading discovered by singer Kate Smith. He later reasons why television became a staple in moved to WNBC in New York City. The American living rooms. Each week young character of “Howdy Doody” began on Bob children watched the antics of Clarabelle the Smith’s radio program, Triple B Ranch, in Clown, Mr. Bluster and an attractive Indian 1947. At that time, Bob Smith was voicing a Princess named Summerfall-Winterspring. character named Elmer who always greeted Howdy Doody had red hair, 48 freckles (one the children in the audience with “Howdy for each State of the Union) and was voiced Doody, Kids!” Soon the children were calling by Bob Smith himself. Elmer by the name of “Howdy Doody.” Later in 1947, Howdy Doody made his television The Howdy Doody Show was a television debut and grew to popularity. In 1950, Smith program of historic firsts. It was Howdy gave up his radio show to devote full time Doody’s face that appeared on the NBC color to The Howdy Doody Show on television. test pattern beginning in 1954, was the first children’s program telecast in color on NBC, and was the first children’s program to be broadcast five days a week. On the afternoon of February 12, 1952, The Howdy Doody th Show reached celebrating its 1,000 telecast. -

The History of NBC New York Television Studios, 1935-1956"

`1 | P a g e "The History of NBC New York Television Studios, 1935-1956" Volume 1 of 2 (Revised) 5 Rare Interior Photos of The International Theater added on page 64 By Bobby Ellerbee And Eyes Of A Generation.com Preface and Acknowledgement This is the first known chronological listing that details the conversions of NBC’s Radio City studios at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York City. Also included in this exclusive presentation by and for Eyes Of A Generation, are the outside performance theaters and their conversion dates to NBC Television theaters. This compilation gives us the clearest and most concise guide yet to the production and technical operations of television’s early days and the network that pioneered so much of the new medium. As you will see, many shows were done as “remotes” in NBC radio studios with in-house mobile camera units, and predate the official conversion date which signifies the studio now has its own control room and stage lighting. Eyes Of A Generation would like to offer a huge thanks to the many past and present NBC people that helped, but most especially to Frank Merklein (NBC 1947-1961) Joel Spector (NBC 1965-2001), Dennis Degan (NBC 2003 to present), historian David Schwartz (GSN) and Gady Reinhold (CBS 1966 to present), for their first hand knowledge, photos and help. This presentation is presented as a public service by the world’s ultimate destination for television history…The Eyes Of A Generation. –Bobby Ellerbee http://www.eyesofageneration.com/ https://www.facebook.com/pages/Eyes-Of-A-Generationcom/189359747768249 `2 | P a g e "The History of NBC New York Television Studios, 1935-1956" Volume 1 of 2 Contents Please Note: Converted should be understood as the debut date of the facility as an exclusive TV studio, now equipped with its own control room. -

Quiz Show” Scandals to Teach Issues of Ethics and the Media in a Business Law Class

North East Journal of Legal Studies Volume 35 Spring/Fall 2016 Article 5 3-20-2017 Using the “Quiz Show” Scandals to Teach Issues of Ethics and the Media in a Business Law Class Sharlene A. McEvoy Fairfield Universty, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/nealsb Recommended Citation McEvoy, Sharlene A. (2017) "Using the “Quiz Show” Scandals to Teach Issues of Ethics and the Media in a Business Law Class," North East Journal of Legal Studies: Vol. 35 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/nealsb/vol35/iss1/5 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 91 / Vol 35 / North East Journal of Legal Studies Using the “Quiz Show” Scandals to Teach Issues of Ethics and the Media in a Business Law Class by Dr. Sharlene A. McEvoy ABSTRACT It was a big deal in the late 1950s but many students have difficulty understanding what the fuss was all about when it was revealed that television quiz shows were rigged. -

The University of St. Thomas Odyssey Program

index file:///C:/Documents%20and%20Settings/sangstj/Desktop/web%20pages... The University of St. Thomas Odyssey Program Fall 2008 I. Course Description and Objectives: Welcome to the Odyssey Program! “Odyssey” is a one-credit, first-semester class, consisting of one-hour, small-group discussions of an important text every Friday afternoon during the fall semester. The Odyssey Program is intended to help students achieve the following objectives: Our hope is that first‑semester freshmen will: · become acquainted with university life; · become acquainted with Catholic higher education, and UST in particular; · begin to develop the skills that will facilitate their success at UST; · develop an understanding of and appreciation for the university core curriculum; · develop an appreciation of the different "ways of knowing" characteristic of each of the major disciplines and the methodology unique to a particular core discipline or area; · acquire strategies to improve reading, writing, and research competencies; · develop an understanding of the interrelationship across disciplines of the core curriculum; and · develop an understanding of and appreciation for the relevance of the core curriculum in preparing students for effective living. II. What Will Be Expected of Students Each Week: 1. 25-35 pages of reading per week. 2. Completion of an on-line weekly reading quiz via Blackboard prior to class. 3. Attendance at weekly discussion sections. 4. Arrive at class with 3 possible questions for discussion. 5. A five-minute reflection paper at the end of each class. III. List of Readings: 1. Josef Pieper, Leisure the Basis of Culture, tr. Gerard Malsbary (South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 1998). -

CLASS DISMISSED HOW TV FRAMES the WORKING CLASS TRANSCRIPT Class Dismissed How TV Frames the Working Class

MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATION Media Education Foundation | 60 Masonic St. Northampton, MA 01060 | TEL 800.897.0089 | [email protected] | www.mediaed.org CLASS DISMISSED HOW TV FRAMES THE WORKING CLASS TRANSCRIPT Class Dismissed How TV Frames the Working Class Writer & Producer: LORETTA ALPER Executive Producer: SUT JHALLY Associate Producers: KENYON KING & KENDRA OLSON Editor: KENYON KING Narrated by ALVIN POUSSAINT, Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and Director of the Media Center, The Judge Baker Children’s Center Featuring Interviews with MELISSA BUTLER, Teacher, Pittsburgh, PA STEVEN EDWARDS, Principal, East Hartford High School, CT ARNOLD FEGE, Director of Public Engagement, Public Engagement Network NELL GEISER, Student, CO CHRIS GERZON, Teacher, Fiske Elementary School, Concord MA HENRY GIROUX, Professor, Penn State University WILLIAM HOYNES, Professor, Vassar College DARBY KAIGHIN-SHIELDS, Student, Pittsburgh, PA NAOMI KLEIN, Author, No Logo: Taking aim at the Brand Bullies BECKY MCCOY, Mother, Montgomery County MD ALEX MOLNAR, Professor, Arizona State University ELAINE NALESKI, Director of Communications, Colorado Springs CO LINDA PAGE, Lead Teacher, CIVA Charter School Colorado Springs CO TOM PANDALEON, Parent, Pittsburgh, PA SENATOR PAUL PINSKY, Maryland State Senator RANDALL TAYLOR, School Board Member, Pittsburgh, PA LAURA WILWORTH, Student, Manchester Essex Regional High School MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATION 60 Masonic St. | Northampton, MA 01060 | TEL 800.897.0089 | [email protected] | www.mediaed.org This transcript may be reproduced for educational, non-profit uses only. © 2006 INTRODUCTION [Opening Music] Fortunate Son [Television clip] How do you do? My name is Dave Garroway and I’m here, and gladly so, to tell you that television is ready for you. -

Zelig You Can't Come Home Again Lydia Rolita "96 Hadn 'Tread the Book

October 4, 1994 3 2 .::O.:.:cto:=;b:.;:e.:...r4~,..:.19:..:9_4____________ The.Gadfly ----------------- CaIDpus News ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Quiz Show's Van Doren abroad and the salary to satisfy his fine tastes. Charles was easily became a recluse. There were job attracted to the phenomenon of quiz shows. offers from a myriad of schools, Charles Van Doren first appeared on the quiz show "Twenty including his alma mater, St. John's. a real-life alum One" on November 28, 1956, and remained deadlocked with the He turned them all down and con D.C. Minutes current champion, Herbert Stempel, until December 5th. Over centrated on his family. Eventually, the next fourteen weeks Van Doren remained undefeated and he took up writing again and be Sam Huzley "95 Gabriel Bell, '98 became the most loved and lauded quiz show cqntestant ev~r. came involved with the Encyclope In the mid 1950's, quiz shows occupied an important role in On the surface, Van Doren was all that America could ~ant .m dia Britannica organization. Cur D.C. Minutes for 9/22/94 and 9/ 27/94 $750.00fortheSwirnClubandweaquaiesced what is now known as the Golden Age of Television. They w~re, an intellectual champion. He was young, white, well bred, rently he is writing fiction and is (abridged) (God, I really kill me) "Mr. Anderson, are you now or have you on the surface, a celebration of human intellect broadcast straight energetic (his sweaty contemplation over various q~estions affiliated with the Aspen Institute. 9fl7/94 ever been male?"-Jolm Dean at the Watergate into the living rooms of America. -

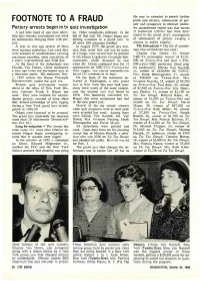

FOOTNOTE to a FRAUD Probe Into Perjury, Subornation of Per- Jury and Conspiracy to Obstruct Justice

life may be extended to permit further FOOTNOTE TO A FRAUD probe into perjury, subornation of per- jury and conspiracy to obstruct justice. Perjury arrests begin in tv quiz investigation An unconfirmed report was that names A sad little band of one time televi- on. Other complaints followed. In the of prominent lawyers had been men- sion quiz winners surrendered last week fall of that year Mr. Hogan began pre- tioned in the grand jury's investigation on indictments charging them with per- senting witnesses to a grand jury. In of subornation of perjury (urging a jury. all some 200 witnesses testified. witness to testify falsely). A year or two ago several of them In August 1959, the grand jury min- The Defendants The list of contest- were national celebrities. Last week they utes, then under lock and key by order ants who surrendered last week: were accused of misdemeanors carrying of a judge, were turned over by petition Charles Van Doren, 34, former maximum penalties, upon conviction, of to the House Legislative Oversight Sub- NBC -TV personality, winner of $129,- a year's imprisonment and $500 fine. committee, which climaxed its case 000 on Twenty-One and later a $50,- At the head of the defendants was when Mr. Doren confessed that his 14 000 -a -year NBC performer (fired after Charles Van Doren, whose confession appearances on NBC -TV's Twenty -One his confession); Elfrida Von Nardoff, a year ago killed the big -money quiz as were rigged. The Harris subcommittee 35, winner of $220,500 on Twenty- a television staple. -

Teip Dennis Hart

Lad Greinit Radio Sho ••••••••••• teip Th inside of ne work great tprop_ 41111 Dennis Hart Monitor The Last Great Radio Show Dennis Hart Writers Club Press San Jose New York Lincoln Shanghai Monitor The Last Great Radio Show All Rights Reserved 0 2002 by Dennis Hart No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the publisher. Writers Club Press an imprint of iUniverse, Inc. For information address: iUniverse, Inc. 5220 S. 16th St., Suite 200 Lincoln, NE 68512 www.iuniverse.com ISBN: 0-595-21395-2 Printed in the United States of America Monitor . .. TO the men and women who made Monitor Foreword This book took about 40 years to write—and if that seems atad too long, let me hasten to explain. Iwas about 12 years old when, one Saturday in the living room in my California home, Iwas twisting the dial on my parents' big Grunow All- Wave Radio, looking for my favorite rock-radio station. What Iheard was, well, life-changing. Some strange, off-the-wall sound coming from that giant radio compelled me to stay tuned to aprogram I'd never encountered before—a show that sounded Very Big Time. For one thing, aguy Iknew as "Mr. Magoo" was hosting it—Jim Backus. What in the world was be doing on the radio? He was hosting Monitor, of course. And the sound that beckoned me was, of course, The Beacon—the Monitor Beacon. -

Louis Martin 31*35 Indiana Ave., Chicago 16, Calumet 3-5656

Louis Martin 31*35 Indiana Ave., Chicago 16, CAlumet 3-5656 DEFeHDE'l HONOR HOLL CITES LAVS GARROWAY, HOUSEWIFE WHO INSPIRED BIS BOYCOTT, 11* CHICAGO, January 12 — Television star Dave Garroway, and housewife who inspired the Montgomery, Ala, bus boycott, are among 11* individuals and two groups named to the Chicago Defender Honor Roll for 1956. The impact of desegregation in public schools and public transpor tation on American life is reflected in half the 16 citations. Six whites and eight Negroes are honored in the annual selections announced today by John H. Sengstacke, editor and publisher of the Defender. The student body of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College at Tallahassee, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People are the groups cited. The Honor Holl was created by the Defender to give recognition to those individuals and groups who did most in the preceding years to strengthen democracy at home, and peace in the world. Past Honor Rolls have cited president Dwight D. Eisenhower, Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dr. Ralph Bunche, Jackie Robinson and Mme. V. L. Pandit. In announcing the selections, Sengstacke declared: ”We have moved so rapidly toward complete freedom of movement in some areas in 1956, that the full significance of many events in the succession of judicial orders and individual acts has not always been apparent. -2- News Release "No doubt all of those cited by us did not foresee the far reaching effects of their efforts.. But by their achievements, by their resistance to oppression, and by their dedication to compliance with the law of the land they have demonstrated the highest expression of democracy." Selection to the Honor Roll is by the editors of the Defender. -

In an Enemy of the People, As We Watch Brothers Battle Over the Fate

TunedBy Kellie Mecleary, Production Dramaturg, and Matthew Buckley Smith In In An Enemy of the People, as we watch brothers battle over the fate of their town, it is worth noting the role that the town paper, The People’s Daily Messenger, plays—the various ways in which it contributes to the machinations and outcome of the plot. The paper is a powerful tool, and its use in the play reflects the use of mass media in other times. In Arthur Miller’s day, the media that was fast becoming a central part of American life was television: as it grew in scope and influence, it took on the role of both informing and reflecting American society and culture. These pages provide an overview of the late ’50s and early ’60s through the major shows and events that dominated the small screen at the time. I Love Lucy used his celebrity to run for president in technology wholeheartedly. The television For the dazzling, six-year run of the show, 1952, gaining almost 40 times as many program Disneyland skillfully promoted an I Love Lucy would remain conservative votes in Democratic primary elections as eponymous amusement park that opened in content and innovative in technique. Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson. Party several months later to such popularity Lucy, the scheming, ebullient housewife leadership, however, favored Stevenson, that in only two-and-a-half years it marked of Cuban bandleader Ricky Ricardo, never who went on to lose to General Dwight its 10-millionth visitor. With a hit theme earns her own money but never stops D.