CLASS DISMISSED HOW TV FRAMES the WORKING CLASS TRANSCRIPT Class Dismissed How TV Frames the Working Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975 History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Decadence 1969-76 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") As usual, the "dark age" of the early 1970s, mainly characterized by a general re-alignment to the diktat of mainstream pop music, was breeding the symptoms of a new musical revolution. In 1971 Johnny Thunders formed the New York Dolls, a band of transvestites, and John Cale (of the Velvet Underground's fame) recorded Jonathan Richman's Modern Lovers, while Alice Cooper went on stage with his "horror shock" show. In London, Malcom McLaren opened a boutique that became a center for the non-conformist youth. The following year, 1972, was the year of David Bowie's glam-rock, but, more importantly, Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell formed the Neon Boys, while Big Star coined power-pop. Finally, unbeknownst to the masses, in august 1974 a new band debuted at the CBGB's in New York: the Ramones. The future was brewing, no matter how flat and bland the present looked. Decadence-rock 1969-75 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Rock'n'roll had always had an element of decadence, amorality and obscenity. In the 1950s it caused its collapse and quasi-extinction. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE TELEVISED SOUTH: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DOMINANT READINGS OF SELECT PRIME-TIME PROGRAMS FROM THE REGION By COLIN PATRICK KEARNEY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2020 © 2020 Colin P. Kearney To my family ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A Doctor of Philosophy signals another rite of passage in a career of educational learning. With that thought in mind, I must first thank the individuals who made this rite possible. Over the past 23 years, I have been most fortunate to be a student of the following teachers: Lori Hocker, Linda Franke, Dandridge Penick, Vickie Hickman, Amy Henson, Karen Hull, Sonya Cauley, Eileen Head, Anice Machado, Teresa Torrence, Rosemary Powell, Becky Hill, Nellie Reynolds, Mike Gibson, Jane Mortenson, Nancy Badertscher, Susan Harvey, Julie Lipscomb, Linda Wood, Kim Pollock, Elizabeth Hellmuth, Vicki Black, Jeff Melton, Daniel DeVier, Rusty Ford, Bryan Tolley, Jennifer Hall, Casey Wineman, Elaine Shanks, Paulette Morant, Cat Tobin, Brian Freeland, Cindy Jones, Lee McLaughlin, Phyllis Parker, Sue Seaman, Amanda Evans, David Smith, Greer Stene, Davina Copsy, Brian Baker, Laura Shull, Elizabeth Ramsey, Joann Blouin, Linda Fort, Judah Brownstein, Beth Lollis, Dennis Moore, Nathan Unroe, Bob Csongei, Troy Bogino, Christine Haynes, Rebecca Scales, Robert Sims, Ian Ward, Emily Watson-Adams, Marek Sojka, Paula Nadler, Marlene Cohen, Sheryl Friedley, James Gardner, Peter Becker, Rebecca Ericsson, -

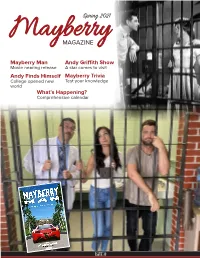

Spring 2021 Mayberry Magazine

Spring 2021 MayberryMAGAZINE Mayberry Man Andy Griffith Show Movie nearing release A star comes to visit Andy Finds Himself Mayberry Trivia College opened new Test your knowledge world What’s Happening? Comprehensive calendar ISSUE 30 Table of Contents Cover Story — Finally here? Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, work on the much ballyhooed Mayberry Man movie has continued, working around delays, postponements, and schedule changes. Now, the movie is just a few months away from release to its supporters, and hopefully, a public debut not too long afterward. Page 8 Andy finds himself He certainly wasn’t the first student to attend the University of North Carolina, nor the last, but Andy Griffith found an outlet for his creative talents at the venerable state institution, finding himself, and his career path, at the school. Page 4 Guest stars galore Being a guest star on “The Andy Griffith Show” could be a launching pad for young actors, and even already established stars sometimes wanted the chance to work with the cast and crew there. But it was Jean Hagen, driving a fast car and doing some smooth talking, who was the first established star to grace the set. Page 6 What To Do, What To Do… The pandemic put a halt to many shows and events over the course of 2020, but there might very well be a few concerts, shows, and events stirring in Mount Airy — the real-life Mayberry — this spring and summer. Page 10 SPRING 2021 SPRING So, You Think You Know • The Andy Griffith Show? Well, let’s see just how deep your knowledge runs. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

Dave Black: a Publisher's Perspective by Rick Mattingly

Dave Black: a Publisher’s Perspective By Rick Mattingly ave Black serves as Vice President and Another mistake I often see are people RM: I often saw books that came from teachers Editor-in-Chief, School & Church who try to write the bible of whatever sub- who said, “Instead of students having to buy Publications, for Alfred Music Pub- ject they’re teaching, and they send in a 200- several different drum books, this one book has Dlishing Company. A prolific composer page manuscript. No one is going to publish everything they need!” It would have a little bit and arranger, more than 60 of his composi- a book that size. Had they talked to the about reading, a little bit about rudiments, a tions and arrangements have been published publisher in advance and asked for a recom- couple of pages of Stick Control-type exercises, by Alfred, Barnhouse, CPP/Belwin, TRN, mended page count, they could have saved a little bit of rock drumset, a little bit of jazz Highland/Etling, and Warner Bros. Black themselves a lot of time. drumset, a little bit about fills, a little double has written for the bands of Louie Bellson, bass, a little odd-time stuff—a little bit of a lot RM: Sammy Nestico, Bill Watrous, Bobby Shew, Ed Based on what I saw when I used to review of things, but not enough of anything. Shaughnessy, Gordon Brisker, and the C.S.U., manuscripts for Hal Leonard, how many times DB: Right. The typical cover letter I often Northridge Jazz Ensemble. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

The Hunger Games: an Indictment of Reality Television

The Hunger Games: An Indictment of Reality Television An ELA Performance Task The Hunger Games and Reality Television Introductory Classroom Activity (30 minutes) Have students sit in small groups of about 4-5 people. Each group should have someone to record their discussion and someone who will report out orally for the group. Present on a projector the video clip drawing comparisons between The Hunger Games and shows currently on Reality TV: (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wdmOwt77D2g) After watching the video clip, ask each group recorder to create two columns on a piece of paper. In one column, the group will list recent or current reality television shows that have similarities to the way reality television is portrayed in The Hunger Games. In the second column, list or explain some of those similarities. To clarify this assignment, ask the following two questions: 1. What are the rules that have been set up for The Hunger Games, particularly those that are intended to appeal to the television audience? 2. Are there any shows currently or recently on television that use similar rules or elements to draw a larger audience? Allow about 5 to 10 minutes for students to work in their small groups to complete their lists. Have students report out on their group work, starting with question #1. Repeat the report out process with question #2. Discuss as a large group the following questions: 1. The narrator in the video clip suggests that entertainments like The Hunger Games “desensitize us” to violence. How true do you think this is? 2. -

Download-To-Own and Online Rental) and Then to Subscription Television And, Finally, a Screening on Broadcast Television

Exporting Canadian Feature Films in Global Markets TRENDS, OPPORTUNITIES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS MARIA DE ROSA | MARILYN BURGESS COMMUNICATIONS MDR (A DIVISION OF NORIBCO INC.) APRIL 2017 PRODUCED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF 1 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA), in partnership with the Association québécoise de la production médiatique (AQPM), the Cana- da Media Fund (CMF), and Telefilm Canada. The following report solely reflects the views of the authors. Findings, conclusions or recom- mendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders of this report, who are in no way bound by any recommendations con- tained herein. 2 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Executive Summary Goals of the Study The goals of this study were three-fold: 1. To identify key trends in international sales of feature films generally and Canadian independent feature films specifically; 2. To provide intelligence on challenges and opportunities to increase foreign sales; 3. To identify policies, programs and initiatives to support foreign sales in other jurisdic- tions and make recommendations to ensure that Canadian initiatives are competitive. For the purpose of this study, Canadian film exports were defined as sales of rights. These included pre-sales, sold in advance of the completion of films and often used to finance pro- duction, and sales of rights to completed feature films. In other jurisdictions foreign sales are being measured in a number of ways, including the number of box office admissions, box of- fice revenues, and sales of rights. -

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act

The Straw that Broke the Camel's Back? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act ERIC C. RUSNAK* The public lands of the United States have always provided the arena in which we Americans have struggled to fulfill our dreams. Even today dreams of wealth, adventure, and escape are still being acted out on these far flung lands. These lands and the dreams-fulfilled and unfulfilled-which they foster are a part of our national destiny. They belong to all Americans. 1 I. INTRODUCTION For some Americans, public lands are majestic territories for exploration, recreation, preservation, or study. Others depend on public lands as a source of income and livelihood. And while a number of Americans lack awareness regarding the opportunities to explore their public lands, all Americans attain benefits from these common properties. Public land affect all Americans. Because of the importance of these lands, heated debates inevitably arise regarding their use or nonuse. The United States Constitution grants to Congress the "[p]ower to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the... Property belonging to the United States." 2 Accordingly, Congress, the body representing the populace, determines the various uses of our public lands. While the Constitution purportedly bestows upon Congress sole discretion to manage public lands, the congressionally-enacted Antiquities Act conveys some of this power to the president, effectively giving rise to a concurrent power with Congress to govern public lands. On September 18, 1996, President William Jefferson Clinton issued Proclamation 69203 under the expansive powers granted to the president by the Antiquities Act4 ("the Act") establishing, in the State of Utah, the Grand * B.A., Wittenberg University, 2000; J.D., The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, 2003 (expected). -

Culture and Identity

AS Sociology For AQA [2nd Edition] Unit 1: Culture and Identity Chris. Livesey and Tony Lawson Unit 1: Culture and Identity Contents 1. Different conceptions of culture, including subculture, mass 2 culture, high and low culture, popular culture, global culture. 2. The Socialisation Process and the Role of Agencies of 15 Socialisation. 3. Sources and Different Conceptions of the Self, Identity and 21 Difference. 4. The Relationship of Identity to Age, Disability, Ethnicity, 30 Gender, Nationality, Sexuality and Social Class in Contemporary Society. 5. Leisure, consumption and identity. 53 1. Different conceptions of culture, including subculture, mass culture, high and low culture, popular culture, global culture. Secondly, we can note a basic distinction between two Culture: Introduction dimensions of culture: Material culture consists of the physical objects Culture is a significant concept for sociologists because (“artifacts”), such as cars, mobile phones and books, a it both identifies a fundamental set of ideas about what society produces and which reflect cultural knowledge, sociologists’ study and suggests a major reason for the skills, interests and preoccupations. existence of Sociology itself – that human social behaviour can be explained in the context of the social Non-Material culture, on the other hand, consists of the groups into which people are born and within which knowledge and beliefs that influence people’s they live their lives. behaviour. In our culture, for example, behaviour may be influenced by religious beliefs (such as Christianity, In this Chapter we’re going to explore a range of ideas Islam or Buddhism) and / or scientific beliefs – your relating to both culture and its counterpart, identity view of human evolution, for example, has probably and to do this we need to develop both a working been influenced by Darwin’s (1859) theories. -

Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 Paul L. Robertson Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Appalachian Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons © Paul L. Robertson Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5854 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robertson i © Paul L. Robertson 2019 All Rights Reserved. Robertson ii The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. By Paul Lester Robertson Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2000 Master of Arts in Appalachian Studies, Appalachian State University, 2004 Master of Arts in English, Appalachian State University, 2010 Director: David Golumbia Associate Professor, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2019 Robertson iii Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank his loving wife A. Simms Toomey for her unwavering support, patience, and wisdom throughout this process. I would also like to thank the members of my committee: Dr. David Golumbia, Dr. -

Be Sure to MW-Lv/Ilci

Page 12 The Canadian Statesman. Bowmanville. April 29, 1998 Section Two From page 1 bolic vehicle taking its riders into other promised view from tire window." existences. Fit/.patriek points to a tiny figure peer In the Attic ing out of an upstairs window on an old photograph. He echoes that image in a Gwen MacGregor’s installation in the new photograph, one he took looking out attic uses pink insulation, heavy plastic of the same window with reflection in the and a very slow-motion video of wind glass. "I was playing with the idea of mills along with audio of a distant train. absence and presence and putting shifting The effect is to link the physical elements images into the piece." of the mill with the artist’s own memories growing up on the prairies. Train of Thought In her role as curator for the VAC, Toronto area artists Millie Chen and Rodgers attempts to balance the expecta Evelyn Michalofski collaborated on the tions of serious artists in the community Millery, millery, dustipoll installation with the demands of the general popula which takes its title from an old popular tion. rhyme. “There has to be a cultural and intel TeddyBear Club Holds Workshop It is a five-minute video projected onto lectual feeding," she says, and at the same Embroidered noses, button eyes, fuzzy cars, and adorable faces arc the beginnings of a beautiful teddy bear. three walls in a space where the Soper time, we have to continue to offer the So say the members of the Bowmanville Teddy Bear Club.