The University of St. Thomas Odyssey Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural & Heritagetourism

Cultural & HeritageTourism a Handbook for Community Champions A publication of: The Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers’ Table on Culture and Heritage (FPT) Table of Contents The views presented here reflect the Acknowledgements 2 Section B – Planning for Cultural/Heritage Tourism 32 opinions of the authors, and do not How to Use this Handbook 3 5. Plan for a Community-Based Cultural/Heritage Tourism Destination ������������������������������������������������ 32 necessarily represent the official posi- 5�1 Understand the Planning Process ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 32 tion of the Provinces and Territories Developed for Community “Champions” ��������������������������������������� 3 which supported the project: Handbook Organization ����������������������������������������������������� 3 5�2 Get Ready for Visitors ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 33 Showcase Studies ���������������������������������������������������������� 4 Alberta Showcase: Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump and the Fort Museum of the NWMP Develop Aboriginal Partnerships ��� 34 Learn More… �������������������������������������������������������������� 4 5�3 Assess Your Potential (Baseline Surveys and Inventory) ������������������������������������������������������������� 37 6. Prepare Your People �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 41 Section A – Why Cultural/Heritage Tourism is Important 5 6�1 Welcome -

Joe Henderson: a Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-5-2016 Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2016 JOEL GEOFFREY HARRIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School JOE HENDERSON: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF HIS LIFE AND CAREER A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Joel Geoffrey Harris College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Jazz Studies December 2016 This Dissertation by: Joel Geoffrey Harris Entitled: Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Music, Program of Jazz Studies Accepted by the Doctoral Committee __________________________________________________ H. David Caffey, M.M., Research Advisor __________________________________________________ Jim White, M.M., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Socrates Garcia, D.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen Luttmann, M.L.S., M.A., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense ________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _______________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Harris, Joel. Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career. Published Doctor of Arts dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, December 2016. This study provides an overview of the life and career of Joe Henderson, who was a unique presence within the jazz musical landscape. It provides detailed biographical information, as well as discographical information and the appropriate context for Henderson’s two-hundred sixty-seven recordings. -

Timeless Experience

Timeless Experience Timeless Experience: Laura Perls’s Unpublished Notebooks and Literary Texts 1946-1985 Edited by Nancy Amendt-Lyon Timeless Experience: Laura Perls’s Unpublished Notebooks and Literary Texts 1946-1985 Series: The World of Contemporary Gestalt Therapy Series Editor: Philip Brownell Edited by Nancy Amendt-Lyon This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Nancy Amendt-Lyon All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8889-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8889-9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..................................................................................... vii Series Editor’s Introduction ........................................................................ ix Editor’s Introduction .................................................................................. xi Chapter I ...................................................................................................... 1 Timeless Experience of a Total Life Crystalized, dated 1976 Chapter II ..................................................................................................... 3 Notebook 1, -

St. Bernard School Is Something So Very Personal to Me and Has Been a Part of My Life Since I Was About Five Years Old

St. Bernard School is something so very personal to me and has been a part of my life since I was about five years old. It was at that time that I would hear my grandfather talking about a dream, that he and some other community members had, to bring Catholic based education back to our community. It was unbelievable and sounded amazing to me. Well that dream quickly became a reality and I began St. Bernard School as a second grader back in 1982. So, St. Bernard has been my school, our community’s school, Sophia and Christian Noah’s school from day one. Although the appearance of our school has changed through the years, one thing has remained the same….a solid opportunity for the children of St. Martin Parish, to receive a well-rounded Catholic education. No matter how large the school gets, I will forever call it our “little school”. Upon entering the front gates there is such a welcoming sense of community and unity. We are a family. You can feel it. Whether in the arts, smarts, sports or as a volunteer; there is something for every child and parent alike. Like I always tell my two children, you get back what you put in; and this school has given back so much to my family. We love our school! The Finch Family: Alyson (’89), Sophia (’15) Christian Noah (’21) & Jeremy We love everything about St. Bernard school. Catholic education, small classes and personal relationships were a must for our son with a good learning environment. -

How Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom Negotiate the Experience of Illness As They Transition from Healthy Warrior to Sick Veteran Jodie L

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School June 2018 “Livin’ the Dream?” How Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom Negotiate the Experience of Illness as They Transition from Healthy Warrior to Sick Veteran Jodie L. Sweezey University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Sweezey, Jodie L., "“Livin’ the Dream?” How Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom Negotiate the Experience of Illness as They rT ansition from Healthy Warrior to Sick Veteran" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7370 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Livin’ the Dream?” How Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom Negotiate the Experience of Illness as They Transition from Healthy Warrior to Sick Veteran by Jodie L. Sweezey A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Bird, Ph.D. Daniel Lende, Ph.D. Rebecca Zarger, Ph.D. Jason Lind, Ph.D. Kevin Kip, Ph.D., FAHA Martin Steele, Lieutenant General (Retired) USMC Date of Approval: June 4, 2018 Keywords: military, disease, exposure Copyright © 2018, Jodie L. Sweezey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend a very special thank you Dr. -

Quiz Show” Scandals to Teach Issues of Ethics and the Media in a Business Law Class

North East Journal of Legal Studies Volume 35 Spring/Fall 2016 Article 5 3-20-2017 Using the “Quiz Show” Scandals to Teach Issues of Ethics and the Media in a Business Law Class Sharlene A. McEvoy Fairfield Universty, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/nealsb Recommended Citation McEvoy, Sharlene A. (2017) "Using the “Quiz Show” Scandals to Teach Issues of Ethics and the Media in a Business Law Class," North East Journal of Legal Studies: Vol. 35 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/nealsb/vol35/iss1/5 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 91 / Vol 35 / North East Journal of Legal Studies Using the “Quiz Show” Scandals to Teach Issues of Ethics and the Media in a Business Law Class by Dr. Sharlene A. McEvoy ABSTRACT It was a big deal in the late 1950s but many students have difficulty understanding what the fuss was all about when it was revealed that television quiz shows were rigged. -

Cultural & Heritage Tourism: a Handbook for Community Champions

Cultural & HeritageTourism a Handbook for Community Champions Table of Contents The views presented here reflect the Acknowledgements 2 opinions of the authors, and do not How to Use this Handbook 3 necessarily represent the official posi- tion of the Provinces and Territories Developed for Community “Champions” ��������������������������������������� 3 which supported the project: Handbook Organization ����������������������������������������������������� 3 Showcase Studies ���������������������������������������������������������� 4 Learn More… �������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Section A – Why Cultural/Heritage Tourism is Important 5 1. Cultural/Heritage Tourism and Your Community ��������������������������� 5 1�1 Treasuring Our Past, Looking To the Future �������������������������������� 5 1�2 Considering the Fit for Your Community ���������������������������������� 6 2. Defining Cultural/Heritage Tourism ��������������������������������������� 7 2�1 The Birth of a New Economy �������������������������������������������� 7 2�2 Defining our Sectors ��������������������������������������������������� 7 2�3 What Can Your Community Offer? �������������������������������������� 10 Yukon Showcase: The Yukon Gold Explorer’s Passport ����������������������� 12 2�4 Benefits: Community Health and Wellness ������������������������������� 14 3. Cultural/Heritage Tourism Visitors: Who Are They? ������������������������ 16 3�1 Canadian Boomers Hit 65 ���������������������������������������������� 16 3�2 Culture as a -

Zelig You Can't Come Home Again Lydia Rolita "96 Hadn 'Tread the Book

October 4, 1994 3 2 .::O.:.:cto:=;b:.;:e.:...r4~,..:.19:..:9_4____________ The.Gadfly ----------------- CaIDpus News ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Quiz Show's Van Doren abroad and the salary to satisfy his fine tastes. Charles was easily became a recluse. There were job attracted to the phenomenon of quiz shows. offers from a myriad of schools, Charles Van Doren first appeared on the quiz show "Twenty including his alma mater, St. John's. a real-life alum One" on November 28, 1956, and remained deadlocked with the He turned them all down and con D.C. Minutes current champion, Herbert Stempel, until December 5th. Over centrated on his family. Eventually, the next fourteen weeks Van Doren remained undefeated and he took up writing again and be Sam Huzley "95 Gabriel Bell, '98 became the most loved and lauded quiz show cqntestant ev~r. came involved with the Encyclope In the mid 1950's, quiz shows occupied an important role in On the surface, Van Doren was all that America could ~ant .m dia Britannica organization. Cur D.C. Minutes for 9/22/94 and 9/ 27/94 $750.00fortheSwirnClubandweaquaiesced what is now known as the Golden Age of Television. They w~re, an intellectual champion. He was young, white, well bred, rently he is writing fiction and is (abridged) (God, I really kill me) "Mr. Anderson, are you now or have you on the surface, a celebration of human intellect broadcast straight energetic (his sweaty contemplation over various q~estions affiliated with the Aspen Institute. 9fl7/94 ever been male?"-Jolm Dean at the Watergate into the living rooms of America. -

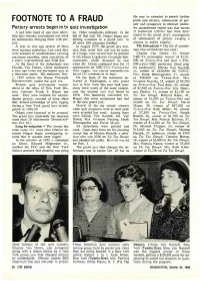

FOOTNOTE to a FRAUD Probe Into Perjury, Subornation of Per- Jury and Conspiracy to Obstruct Justice

life may be extended to permit further FOOTNOTE TO A FRAUD probe into perjury, subornation of per- jury and conspiracy to obstruct justice. Perjury arrests begin in tv quiz investigation An unconfirmed report was that names A sad little band of one time televi- on. Other complaints followed. In the of prominent lawyers had been men- sion quiz winners surrendered last week fall of that year Mr. Hogan began pre- tioned in the grand jury's investigation on indictments charging them with per- senting witnesses to a grand jury. In of subornation of perjury (urging a jury. all some 200 witnesses testified. witness to testify falsely). A year or two ago several of them In August 1959, the grand jury min- The Defendants The list of contest- were national celebrities. Last week they utes, then under lock and key by order ants who surrendered last week: were accused of misdemeanors carrying of a judge, were turned over by petition Charles Van Doren, 34, former maximum penalties, upon conviction, of to the House Legislative Oversight Sub- NBC -TV personality, winner of $129,- a year's imprisonment and $500 fine. committee, which climaxed its case 000 on Twenty-One and later a $50,- At the head of the defendants was when Mr. Doren confessed that his 14 000 -a -year NBC performer (fired after Charles Van Doren, whose confession appearances on NBC -TV's Twenty -One his confession); Elfrida Von Nardoff, a year ago killed the big -money quiz as were rigged. The Harris subcommittee 35, winner of $220,500 on Twenty- a television staple. -

In an Enemy of the People, As We Watch Brothers Battle Over the Fate

TunedBy Kellie Mecleary, Production Dramaturg, and Matthew Buckley Smith In In An Enemy of the People, as we watch brothers battle over the fate of their town, it is worth noting the role that the town paper, The People’s Daily Messenger, plays—the various ways in which it contributes to the machinations and outcome of the plot. The paper is a powerful tool, and its use in the play reflects the use of mass media in other times. In Arthur Miller’s day, the media that was fast becoming a central part of American life was television: as it grew in scope and influence, it took on the role of both informing and reflecting American society and culture. These pages provide an overview of the late ’50s and early ’60s through the major shows and events that dominated the small screen at the time. I Love Lucy used his celebrity to run for president in technology wholeheartedly. The television For the dazzling, six-year run of the show, 1952, gaining almost 40 times as many program Disneyland skillfully promoted an I Love Lucy would remain conservative votes in Democratic primary elections as eponymous amusement park that opened in content and innovative in technique. Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson. Party several months later to such popularity Lucy, the scheming, ebullient housewife leadership, however, favored Stevenson, that in only two-and-a-half years it marked of Cuban bandleader Ricky Ricardo, never who went on to lose to General Dwight its 10-millionth visitor. With a hit theme earns her own money but never stops D. -

Ornette Coleman and Harmolodics by Matt Lavelle

Ornette Coleman and Harmolodics by Matt Lavelle A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written and approved under the direction of Dr. Henry Martin ________________________ Newark, New Jersey May 2019 © 2019 Matt Lavelle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Ornette Coleman stands as one of the most significant innovators in jazz history. The purpose of my thesis is to show where his innovations came from, how his music functions, and how it impacted other innovators around him. I also delved into the more controversial aspects of his music. At the core of his process was a very personal philosophical and musical theory he invented which he called Harmolodics. Harmolodics was derived from the music of Charlie Parker and Coleman’s need to challenge conventional Western music theory in pursuit of providing direct links between music, nature, and humanity. To build a foundation I research Coleman’s development prior to his famous debut at the Five Spot, focusing on evidence of a direct connection to Charlie Parker. I examine his use of instruments he played other than his primary use of the alto saxophone. His relationships with the piano, guitar, and the musicians that played them are then examined. I then research his use of the bass and drums, and the musicians that played them, so vital to his music. I follow with documentation of the string quartets, woodwind ensembles, and symphonic work, much of which was never recorded. -

Guide to the Mortimer J. Adler Papers 1914-1995

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Mortimer J. Adler Papers 1914-1995 © 2006 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Biographical Note 3 Scope Note 5 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 5 INVENTORY 5 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.ADLERM Title Adler, Mortimer J.. Papers Date 1914-1995 Size 224.5 linear feet (154 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Mortimer Jerome Adler, philosopher, educator, writer. The Mortimer J. Adler Papers include information on his work with the Great Books, Encyclopaedia Britannica, and the Institute for Philosophical Research as well as material relating to his many publications. The collection consists of articles, correspondence, manuscripts, memoranda, newspaper clippings, notes, reading lists, reprints, and other materials relating to the career of Mortimer J. Adler. Information on Use Access This collection is open for research but is currently unprocessed and may contain information that falls into certain administrative restriction categories. Administrative and budget material is restricted for up to 50 years. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: Adler, Mortimer J.. Papers, [Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library Biographical Note Mortimer Jerome Adler was born on December 28, 1902 in New York City. His father, Ignatz, an immigrant from Bavaria, worked as a jeweler and his mother, Clarissa, was a former teacher. When he was fourteen, Adler dropped out of DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and went to work as a secretary and a copy boy for the New York Sun.