Lesotho Badger (Mellivora Capensis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Luke Diver, M.A

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 By Luke Diver, M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Head of Department: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisors of Research: Dr David Murphy Dr Ian Speller 2014 i Table of Contents Page No. Title page i Table of contents ii Acknowledgements iv List of maps and illustrations v List of tables in main text vii Glossary viii Maps ix Personalities of the South African War xx 'A loyal Irish soldier' xxiv Cover page: Ireland and the South African War xxv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (October - December 1899) 19 Chapter 2: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (January - March 1900) 76 Chapter 3: The ‘Irish’ Imperial Yeomanry and the battle of Lindley 109 Chapter 4: The Home Front 152 Chapter 5: Commemoration 198 Conclusion 227 Appendix 1: List of Irish units 240 Appendix 2: Irish Victoria Cross winners 243 Appendix 3: Men from Irish battalions especially mentioned from General Buller for their conspicuous gallantry in the field throughout the Tugela Operations 247 ii Appendix 4: General White’s commendations of officers and men that were Irish or who were attached to Irish units who served during the period prior and during the siege of Ladysmith 248 Appendix 5: Return of casualties which occurred in Natal, 1899-1902 249 Appendix 6: Return of casualties which occurred in the Cape, Orange River, and Transvaal Colonies, 1899-1902 250 Appendix 7: List of Irish officers and officers who were attached -

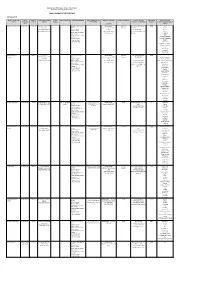

Public Libraries in the Free State

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment

Study Name: Orange River Integrated Water Resources Management Plan Report Title: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Submitted By: WRP Consulting Engineers, Jeffares and Green, Sechaba Consulting, WCE Pty Ltd, Water Surveys Botswana (Pty) Ltd Authors: A Jeleni, H Mare Date of Issue: November 2007 Distribution: Botswana: DWA: 2 copies (Katai, Setloboko) Lesotho: Commissioner of Water: 2 copies (Ramosoeu, Nthathakane) Namibia: MAWRD: 2 copies (Amakali) South Africa: DWAF: 2 copies (Pyke, van Niekerk) GTZ: 2 copies (Vogel, Mpho) Reports: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Review of Surface Hydrology in the Orange River Catchment Flood Management Evaluation of the Orange River Review of Groundwater Resources in the Orange River Catchment Environmental Considerations Pertaining to the Orange River Summary of Water Requirements from the Orange River Water Quality in the Orange River Demographic and Economic Activity in the four Orange Basin States Current Analytical Methods and Technical Capacity of the four Orange Basin States Institutional Structures in the four Orange Basin States Legislation and Legal Issues Surrounding the Orange River Catchment Summary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the study ................................................................................................ -

Of the Nineteenth-Century Maloti- Drakensberg Mountains1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery The ‘Interior World’ of the Nineteenth-Century Maloti- Drakensberg Mountains1 Rachel King*1, 2, 3 and Sam Challis3 1 Centre of African Studies, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom 2 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom 3 Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Over the last four decades archaeological and historical research has the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains as a refuge for Bushmen as the nineteenth-century colonial frontier constricted their lifeways and movements. Recent research has expanded on this characterisation of mountains-as-refugia, focusing on ethnically heterogeneous raiding bands (including San) forging new cultural identities in this marginal context. Here, we propose another view of the Maloti-Drakensberg: a dynamic political theatre in which polities that engaged in illicit activities like raiding set the terms of colonial encounters. We employ the concept of landscape friction to re-cast the environmentally marginal Maloti-Drakensberg as a region that fostered the growth of heterodox cultural, subsistence, and political behaviours. We introduce historical, rock art, and ‘dirt’ archaeological evidence and synthesise earlier research to illustrate the significance of the Maloti-Drakensberg during the colonial period. We offer a revised southeast-African colonial landscape and directions for future research. Keywords Maloti-Drakensberg, Basutoland, AmaTola, BaPhuthi, creolisation, interior world 1 We thank Lara Mallen, Mark McGranaghan, Peter Mitchell, and John Wright for comments on this paper. This research was supported by grants from the South African National Research Foundation’s African Origins Platform, a Clarendon Scholarship from the University of Oxford, the Claude Leon Foundation, and the Smuts Memorial Fund at Cambridge. -

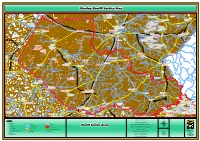

Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme

CALEDon–BLOEMFONTEIN GOVERNMENT WATER SCHEME South Africa Modder Krugersdrift Dam Bloemhof Dam Catchment Mazelspoort Weir LOCATION Bainsvlei W Mockes Dam Kora The Caledon–Modder Transfer Scheme consists of two transfer schemes, namely the original nna Hamilton Park BLOEMFONTEIN Bloemdustria Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and the Novo Transfer scheme, which Brandkop Boesmanskop Bloemspruit Sepane Thaba Nchu are situated in the Upper Orange Catchment. Mo dd De Brug e Seroalo Dam Grootvlei r Newbury Botshabelo Dam Bloemdustria Lovedale DESCRIPTION Kgabanyana Dam W Kle Rustfontein in Lesaka Dam Modder Groothoek The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and Novo Transfer schemes are Dam Armenia W Dam two of the three main schemes used to supplement the Riet–Modder Catchment due to Caledon-Bloemfontein the full utilisation of the water resources within the catchment, the third main scheme Ganna being the Orange–Riet Transfer. The Mazelpoort Scheme was developed by Mangaung Leeu Municipality. The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and Novo Transfer, Riet-Modder together with the Mazelpoort Scheme situated on the Modder River, form one integrated Catchment Uitkyk DEWETSDORP supply system serving the Mangaung area. SOUTH AFRICA The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme is operated by Bloem Water, REDDERSBURG Caledon LESOTHO and consists of Welbedacht, Rustfontein and Knellpoort dams, along with other service Riet reservoirs, pump stations and water treatment works. Peri-urban area/urban area P P Town Knellpoort 3 The storage capacity of the Welbedacht Dam reduced from 115 million m to approximately Dam Tienfontein International boundary 16 million m3 in only 20 years due to siltation. This impacted the assurance of supply to River and dam Welbedacht Dam Bloemfontein and so Knellpoort Dam was constructed (off channel storage) to augment De Hoek Pipeline and reservoir the supply. -

20201101-Fs-Advert Xhariep Sheriff Service Area.Pdf

XXhhaarriieepp SShheerriiffff SSeerrvviiccee AArreeaa UITKYK GRASRANDT KLEIN KAREE PAN VAAL PAN BULTFONTEIN OLIFANTSRUG SOLHEIM WELVERDIEND EDEN KADES PLATKOP ZWAAIHOEK MIDDEL BULT Soutpan AH VLAKPAN MOOIVLEI LOUISTHAL GELUKKIG DANIELSRUST DELFT MARTHINUSPAN HERMANUS THE CRISIS BELLEVUE GOEWERNEURSKOP ROOIPAN De Beers Mine EDEN FOURIESMEER DE HOOP SHEILA KLEINFONTEIN MEGETZANE FLORA MILAMBI WELTEVREDE DE RUST KENSINGTON MARA LANGKUIL ROSMEAD KALKFONTEIN OOST FONTAINE BLEAU MARTINA DORASDEEL BERDINA PANORAMA YVONNE THE MONASTERY JOHN'S LOCKS VERDRIET SPIJT FONTEIN Kimberley SP ROOIFONTEIN OLIFANTSDAM HELPMEKAAR MIMOSA DEALESRUST WOLFPAN ZWARTLAAGTE MORNING STAR PLOOYSBURG BRAKDAM VAALPAN INHOEK CHOE RIETPAN Soetdoring R30 MARIA ATHELOON WATERVAL RUSOORD R709 LOUISLOOTE LAURA DE BAD STOFPUT OPSTAL HERMITAGE WOLVENFONTEIN SUNNYSIDE EERLIJK DORISVILLE ST ZUUR FONTEIN Verkeerdevlei ST LYONSREST R708 UITVAL SANCTUARY SUSANNA BOTHASDAM MERIBA AURORA KALKWAL ^!. VERKEERDEVLEI WATERVAL ZETLAND BELMONT ST SAPS SPITS KOP DIDIMALA LEMOENHOEK WATERVAL ORANGIA SCHOONVLAKTE DWAALHOEK WELTEVREDE GERTJE PAARDEBERG KOPPIES' N8 SANDDAM ZAMENKOMST R64 Nature DIEPHOEK FARMS KARREE KLIMOP MELKVLEY OMDRAAI Mantsopa NU ELYSIUM UMPUKANE HORATIO EUREKA ROODE PAN LK KAMEELPAN KOEDOE`S RAND KLIPFONTEIN DUIKERSDRAAI VLAKLAAGTE ST MIMOSA FAIRFIELD VALAF BEGINSEL Verkeerdevlei SP KOPPIESDAM MELIEFE ZAAIPLAATS PAARDEBERG KARREE DAM ARBEIDSGENOT DOORNLAAGTE EUREKA GELYK TAFELKOP KAREEKOP BOESMANSKOP AHLEN BLAUWKRANS VAN LOVEDALE ALETTA ROODE ESKOL "A" Tokologo NU AANKOMST -

Rural Planning in South Africa: a Case Study

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT Strategies, Planning and Assessment Programme Environmental Planning Issues No. 22, December 2000 Rural Planning in South Africa: A Case Study By Khanya – managing rural change A Report to the UK Department for International Development (Research contract: R72510 Khanya – managing rural change 17 James Scott Street, Brandwag, Bloemfontein 9301 Free State, South Africa Tel: +27-51-430-0712; Fax: +27-51-430-8322 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.khanya-mrc.co.za IIED 3 Endsleigh Street, London WC1H ODD Tel: +44-171-388-2117; Fax: +44-171-388-2826 Contact email: [email protected] Website: http://www.iied.org ISBN: 1 899825 75 4 NOTE This manuscript was completed in November 1999. It has not been possible to include any updates to the text to reflect any changes that might have occurred in terms of legislation, institutional arrangements and key issues. RURAL PLANNING REPORTS This report is one of a suite of four prepared for a study of rural planning experience globally, and published by IIED in its Environmental Planning Issues series: Botchie G. (2000) Rural District Planning in Ghana: A Case Study. Environmental Planning Issues No. 21, International Institute for Environment and Development, London Dalal-Clayton, D.B., Dent D.L. and Dubois O. (1999): Rural Planning in the Developing World with a Special Focus on Natural Resources: Lessons Learned and Potential Contributions to Sustainable Livelihoods: An Overview. Report to UK Department for International Development. Environmental Planning Issues No.20, IIED, London Khanya-mrc (2000) Rural planning in South Africa: A case study. -

Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District Socio�Economic Profile 2007 NO 1 and Development Plans

Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile 2007 NO 1 and development plans Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile and development plans Centre for Development Support (IB 100) University of the Free State PO Box 339 Bloemfontein 9300 South Africa www.ufs.ac.za/cds Please reference as: Centre for Development Support (CDS). 2007. Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile and development plans. CDS Research Report, Arid Areas, 2007(1). Bloemfontein: University of the Free State (UFS). CONTENTS I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 II. Geographic overview ........................................................................................................ 2 1. Namaqualand and Richtersveld ................................................................................................... 3 2. The Karoo................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Gordonia, the Kalahari and Bushmanland .................................................................................... 4 4. General characteristics of the arid areas ....................................................................................... 5 III. The Western Zone (Succulent Karoo) .............................................................................. 8 1. Namakwa District Municipality .................................................................................................. -

Appointment of Sheriffs

STAATSKOERANT, 7 MAART 2014 No. 37419 3 GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 167 OF 2014 the doj & cd Department: Justice and Constitutional Development REPUBUC OF SOUTH AFRICA 27 February 2014 APPOINTMENT OF SHERIFFS I, John Jeffrey, Deputy Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development as the duly delegated authority hereby, under section 2 of the Sheriff's Act, 1986 (Act No. 90 of 1986), appoint the persons listed in the accompanying Schedule as sheriffs in vacant offices corresponding to their names. The appointments take effect on 1 June 2014 or any other date as may be arrangedbetweentheDepartmentofJusticeandConstitutional Development and the persons I have so appointed as sheriffs. The details of the appointed sheriffs including their contact details and business addresses will be published on the website of the South African Board for Sheriffs (www.sheriffs.org.za) as well as that of the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (www.doj.gov.za) before the commencement date of the said appointments. Enquiries in this regard may be made at the South African Board for Sheriffs at the following contact telephone number: 021 426 0577. Given under my Hand at Pretoria on this the 27th day of February 2014. Mr J Jeffery, MP DEPUTY MINISTER OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 4 No. 37419 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 7 MARCH 2014 SCHEDULE EASTERN CAPE NO. APPOINTED PERSON VACANT OFFICE 1 Ms Babalwa Primrose Konjwa Molteno & Sterkstroom High and Lower Courts 2 Mr Luvuyo Jeffrey Leshosi Somerset East Lower Court (will be vacant with effect from 1 July 2014) FREE STATE NO. -

![Repainting of Images on Rock in Australia and the Maintenance of Aboriginal Culture [1988]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7256/repainting-of-images-on-rock-in-australia-and-the-maintenance-of-aboriginal-culture-1988-1707256.webp)

Repainting of Images on Rock in Australia and the Maintenance of Aboriginal Culture [1988]

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269164534 REPAINTING OF IMAGES ON ROCK IN AUSTRALIA AND THE MAINTENANCE OF ABORIGINAL CULTURE [1988] Article in Antiquity · December 1988 DOI: 10.1017/S0003598X00075086 CITATIONS READS 34 212 4 authors, including: Graeme K Ward Australian National University 75 PUBLICATIONS 1,081 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Cosmopolitanism, Social Justice and Global Archaeology View project Pathway Project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Graeme K Ward on 06 December 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. REPAINTING OF IMAGES ON ROCK IN AUSTRALIA AND THE MAINTENANCE OF ABORIGINAL CULTURE [1988] David MOWALJARLAI Wanang Ngari Corporation, PO Box 500, Derby WA 6723 Patricia VINNICOMBE Department of Aboriginal Sites, Western Australian Museum, Perth WA 6005 Graeme K WARD Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Christopher CHIPPINDALE Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ Published in Antiquity 62 (237): 690-696 (December 1988) Introduction This paper has grown out of public and private discussions at the First AURA (Australian Rock Art Research Association) Congress held in Darwin (NT), Australia, in August 1988. DM is a traditional Aboriginal ‘lawman’ concerned to make his viewpoint known to a wider audience following controversy over the repainting of images in rock-shelters in his territory, A highlight of the AURA Congress was the participation of Australian Aboriginal people. They and their ancestors are the source of the painted and engraved images discussed in Australian sections of the conference and seen on field excursions. -

Agri-Park District: Xhariep Province: Free State Reporting Date: March 2016 Key Commodities Agripark Components Status

AGRI-PARK DISTRICT: XHARIEP PROVINCE: FREE STATE REPORTING DATE: MARCH 2016 KEY COMMODITIES AGRIPARK COMPONENTS STATUS 13 FPSUs to be located in: Petrusburg, Edenburg, Red meat (beef and mutton) Luckoff, Smithfield, Bethulie, Koffiefontein, Fauresmith, DAMC Established Venison Zastron, Jacobsdal, Springfontein, Reddersburg, 16 members Aquaculture Philippolis, Rouxville The final Master Business plan was submitted on 29/02/2016 1 Agri-Hub located in Springfontein KEY CATALYTIC PROJECTS 1 AGRORUMC -locatedPROCESSING in Bloemfontein BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES KEY ROLE-PLAYERS Building of an export abattoir that will have Beef: abattoir; freezing; primary butchering; grading Public Sector Industry Other four processing lines for venison, cattle, and labelling; transporting; washing; cleaning; DRDLR SA Veterinary Association ARC sheep and potentially ostrich. The abattoir packaging; storage; leather tanning; semi-dry, DRDAR Red Meat Producers Organisation NEF will be responsible for large scale Dept. of Kroonstad Piggery Farmers MAFISA slaughtering, processing, deboning and cooked and smoked sausages, Agriculture NERPO Glen packaging of different types of meat as Mutton: packaging and branding, drying of pastirma (Petrusburg/ IMQAS Agriculture while adhering to international export and mutton jerky and offal marketing Zastron/ Sparta Foods Institute Koffiefontein) SAMIC SEDA standards. Venison: Mobile abattoirs; game fencing; organic FS Dept. of Association of Meat Importers and Exporters DBSA Development or refurbishment -

FREE STATE DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION Address List: ABET Centres District: XHARIEP

FREE STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Address List: ABET Centres District: XHARIEP Name of centre EMIS Category Hosting School Postal address Physical address Telephone Telephone number code number BA-AGI FS035000 PALC IKANYEGENG PO BOX 40 JACOBSDAL 8710 123 SEDITI STRE RATANANG JACOBSDAL 8710 053 5910112 GOLDEN FOUNTAIN FS018001 PALC ORANGE KRAG PRIMARY PO BOX 29 XHARIEP DAM 9922 ORANJEKRAG HYDROPARK LOCAT XHARIEP 9922 051-754 DAM IPOPENG FS029000 PALC BOARAMELO PO BOX 31 JAGERSFONTEIN 9974 965 ITUMELENG L JAGERSFORNTEIN 9974 051 7240304 KGOTHALLETSO FS026000 PALC ZASTRON PUBLIC PO BOX 115 ZASTRON 9950 447 MATLAKENG S MATLAKENG ZASTRPM 9950 051 6731394 LESEDI LA SETJABA FS020000 PALC EDENBURG PO BOX 54 EDENBURG 9908 1044 VELEKO STR HARASEBEI 9908 051 7431394 LETSHA LA FS112000 PALC TSHWARAGANANG PO BOX 56 FAURESMITH 9978 142 IPOPENG FAURESMITH 9978 051 7230197 TSHWARAGANANG MADIKGETLA FS023000 PALC MADIKGETLA PO BOX 85 TROMPSBURG 9913 392 BOYSEN STRE MADIKGETLA TROMPSBU 9913 051 7130300 RG MASIFUNDE FS128000 PALC P/BAG X1007 MASIFUNDE 9750 GOEDEMOED CORRE ALIWAL NORTH 9750 0 MATOPORONG FS024000 PALC ITEMELENG PO BOX 93 REDDERSBURG 9904 821 LESEDI STRE MATOPORONG 9904 051 5530726 MOFULATSHEPE FS021000 PALC MOFULATSHEPE PO BOX 237 SMITHFIELD 9966 474 JOHNS STREE MOFULATHEPE 9966 051 6831140 MPUMALANGA FS018000 PALC PHILIPPOLIS PO BOX 87 PHILIPPOLIS 9970 184 SCHOOL STRE PODING TSE ROLO PHILIPPOLIS 9970 051 7730220 REPHOLOHILE FS019000 PALC WONGALETHU PO BOX 211 BETHULIE 9992 JIM FOUCHE STR LEPHOI BETHULIE 9992 051 7630685 RETSWELELENG FS033000 PALC INOSENG PO BOX 216 PETRUSBURG 9932 NO 2 BOIKETLO BOIKETLO PETRUSBUR 9932 053 5740334 G THUTONG FS115000 PALC LUCKHOFF PO BOX 141 LUCKHOFF 9982 PHIL SAUNDERS A TEISVILLE LUCKHOFF 9982 053 2060115 TSIBOGANG FS030000 PALC LERETLHABETSE PO BOX 13 KOFFIEFONTEIN 9986 831 LEFAFA STRE DITLHAKE 9986 053 2050173 UBUNTU FS035001 PALS SAUNDERSHOOGTE P.O.