Rural Planning in South Africa: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South African Architectural Record

SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHITECTURAL RECORD fl JULY 1952 i S.A. Architectural Record, July, 1952 SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHITECTURAL RECORD JOURNAL OF THE INSTITUTE OF SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHITECTS; THE CAPE, NATAL, ORANGE FREE STATE AND TRANSVAAL PROVINCIAL INSTITUTES AND THE CHAPTER OF SOUTH AFRICAN QUANTITY SURVEYORS CONTENTS FOR JULY 1952 GROOT DRAKENSTEIN. Luxury Bachelor Apartments in Johan nesburg. Architects: H. H. le Roith and Partners 166 MORKEL & VILJOENS GARAGES. A remodelled Garage in the Cape Province. Architects: Chapman and Cohen 170 RESIDENCE GERSHATER. Architects: H. H. le Roith and Partners 173 EARLY VOORTREKKER HOUSES IN THE SOUTHERN FREE STATE, by James Walton 176 ADDRESS TO THE CENTRAL COUNCIL, by (Retiring) President- in-Chief C. Erik Todd Esq., O.B.E., M.C., A.R.I.B.A., M.I.A. 180 SUMMARY OF CENTRAL COUNCIL ACTIVITIES, COVERING SESSION 1951/52. Paper by the Registrar 181 TRADE NOTES & NEWS 183 BOOK REVIEWS 184 OBITUARY 185 NOTES & NEWS i 85 EDITOR VOLUME 37 The Editor will be glad to consider any MSS., photographs or sketches submitted to him, but they should be accompanied by stamped addressed envelopes for return if W. DUNCAN HOWIE unsuitable. In case of loss or injury he cannot hold himself responsible for MSS., photographs or sketches, and publication in the Journal can alone be taken as evidence ASSISTANT EDITORS of acceptance. The name and address of the owner should be placed on the back of UGO T O M A SELL I all pictures and MSS. The Institute does not hold itself responsible for the opinions expressed by contributors. Annual subscription £1 10s. -

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Luke Diver, M.A

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 By Luke Diver, M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Head of Department: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisors of Research: Dr David Murphy Dr Ian Speller 2014 i Table of Contents Page No. Title page i Table of contents ii Acknowledgements iv List of maps and illustrations v List of tables in main text vii Glossary viii Maps ix Personalities of the South African War xx 'A loyal Irish soldier' xxiv Cover page: Ireland and the South African War xxv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (October - December 1899) 19 Chapter 2: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (January - March 1900) 76 Chapter 3: The ‘Irish’ Imperial Yeomanry and the battle of Lindley 109 Chapter 4: The Home Front 152 Chapter 5: Commemoration 198 Conclusion 227 Appendix 1: List of Irish units 240 Appendix 2: Irish Victoria Cross winners 243 Appendix 3: Men from Irish battalions especially mentioned from General Buller for their conspicuous gallantry in the field throughout the Tugela Operations 247 ii Appendix 4: General White’s commendations of officers and men that were Irish or who were attached to Irish units who served during the period prior and during the siege of Ladysmith 248 Appendix 5: Return of casualties which occurred in Natal, 1899-1902 249 Appendix 6: Return of casualties which occurred in the Cape, Orange River, and Transvaal Colonies, 1899-1902 250 Appendix 7: List of Irish officers and officers who were attached -

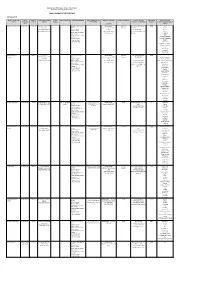

Public Libraries in the Free State

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment

Study Name: Orange River Integrated Water Resources Management Plan Report Title: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Submitted By: WRP Consulting Engineers, Jeffares and Green, Sechaba Consulting, WCE Pty Ltd, Water Surveys Botswana (Pty) Ltd Authors: A Jeleni, H Mare Date of Issue: November 2007 Distribution: Botswana: DWA: 2 copies (Katai, Setloboko) Lesotho: Commissioner of Water: 2 copies (Ramosoeu, Nthathakane) Namibia: MAWRD: 2 copies (Amakali) South Africa: DWAF: 2 copies (Pyke, van Niekerk) GTZ: 2 copies (Vogel, Mpho) Reports: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Review of Surface Hydrology in the Orange River Catchment Flood Management Evaluation of the Orange River Review of Groundwater Resources in the Orange River Catchment Environmental Considerations Pertaining to the Orange River Summary of Water Requirements from the Orange River Water Quality in the Orange River Demographic and Economic Activity in the four Orange Basin States Current Analytical Methods and Technical Capacity of the four Orange Basin States Institutional Structures in the four Orange Basin States Legislation and Legal Issues Surrounding the Orange River Catchment Summary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the study ................................................................................................ -

South Africa)

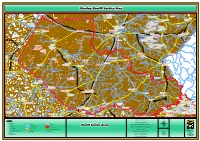

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme

CALEDon–BLOEMFONTEIN GOVERNMENT WATER SCHEME South Africa Modder Krugersdrift Dam Bloemhof Dam Catchment Mazelspoort Weir LOCATION Bainsvlei W Mockes Dam Kora The Caledon–Modder Transfer Scheme consists of two transfer schemes, namely the original nna Hamilton Park BLOEMFONTEIN Bloemdustria Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and the Novo Transfer scheme, which Brandkop Boesmanskop Bloemspruit Sepane Thaba Nchu are situated in the Upper Orange Catchment. Mo dd De Brug e Seroalo Dam Grootvlei r Newbury Botshabelo Dam Bloemdustria Lovedale DESCRIPTION Kgabanyana Dam W Kle Rustfontein in Lesaka Dam Modder Groothoek The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and Novo Transfer schemes are Dam Armenia W Dam two of the three main schemes used to supplement the Riet–Modder Catchment due to Caledon-Bloemfontein the full utilisation of the water resources within the catchment, the third main scheme Ganna being the Orange–Riet Transfer. The Mazelpoort Scheme was developed by Mangaung Leeu Municipality. The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and Novo Transfer, Riet-Modder together with the Mazelpoort Scheme situated on the Modder River, form one integrated Catchment Uitkyk DEWETSDORP supply system serving the Mangaung area. SOUTH AFRICA The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme is operated by Bloem Water, REDDERSBURG Caledon LESOTHO and consists of Welbedacht, Rustfontein and Knellpoort dams, along with other service Riet reservoirs, pump stations and water treatment works. Peri-urban area/urban area P P Town Knellpoort 3 The storage capacity of the Welbedacht Dam reduced from 115 million m to approximately Dam Tienfontein International boundary 16 million m3 in only 20 years due to siltation. This impacted the assurance of supply to River and dam Welbedacht Dam Bloemfontein and so Knellpoort Dam was constructed (off channel storage) to augment De Hoek Pipeline and reservoir the supply. -

South African Jewish Board of Deputies Report of The

The South African Jewish Board of Deputies JL 1r REPORT of the Executive Council for the period July 1st, 1933, to April 30th, 1935. To be submitted to the Eleventh Congress at Johannesburg, May 19th and 20th, 1935. <י .H.W.V. 8. Co י É> S . 0 5 Americanist Commiitae LIBRARY 1 South African Jewish Board of Deputies. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL. President : Hirsch Hillman, Johannesburg. Vice-President» : S. Raphaely, Johannesburg. Morris Alexander, K.C., M.P., Cape Town. H. Moss-Morris, Durban. J. Philips, Bloemfontein. Hon. Treasurer: Dr. Max Greenberg. Members of Executive Council: B. Alexander. J. Alexander. J. H. Barnett. Harry Carter, M.P.C. Prof. Dr. S. Herbert Frankel. G. A. Friendly. Dr. H. Gluckman. J. Jackson. H. Katzenellenbogen. The Chief Rabbi, Prof. Dr. j. L. Landau, M.A., Ph.D. ^ C. Lyons. ^ H. H. Morris Esq., K.C. ^י. .B. L. Pencharz A. Schauder. ^ Dr. E. B. Woolff, M.P.C. V 2 CONSTITUENT BODIES. The Board's Constituent Bodies are as. follows :— JOHANNESBURG (Transvaal). 1. Anykster Sick Benefit and Benevolent Society. 2. Agoodas Achim Society. 3. Beth Hamedrash Hagodel. 4. Berea Hebrew Congregation. 5. Bertrams Hebrew Congregation. 6. Braamfontein Hebrew Congregation. 7. Chassidim Congregation. 8. Club of Polish Jews. 9. Doornfontein Hebrew:: Congregation.^;7 10. Eastern Hebrew Benevolent Society. 11. Fordsburg Hebrew Congregation. 12. Grodno Sifck Benefit and Benevolent Society. 13. Habonim. 14. Hatechiya Organisation. 15. H.O.D. Dr. Herzl Lodge. 16. H.O.D. Sir Moses Montefiore Lodge. 17. Jeppes Hebrew Congregation, 18. Johannesburg Jewish Guild. 19. Johannesburg Jewish Helping Hand and Burial Society. -

20201101-Fs-Advert Xhariep Sheriff Service Area.Pdf

XXhhaarriieepp SShheerriiffff SSeerrvviiccee AArreeaa UITKYK GRASRANDT KLEIN KAREE PAN VAAL PAN BULTFONTEIN OLIFANTSRUG SOLHEIM WELVERDIEND EDEN KADES PLATKOP ZWAAIHOEK MIDDEL BULT Soutpan AH VLAKPAN MOOIVLEI LOUISTHAL GELUKKIG DANIELSRUST DELFT MARTHINUSPAN HERMANUS THE CRISIS BELLEVUE GOEWERNEURSKOP ROOIPAN De Beers Mine EDEN FOURIESMEER DE HOOP SHEILA KLEINFONTEIN MEGETZANE FLORA MILAMBI WELTEVREDE DE RUST KENSINGTON MARA LANGKUIL ROSMEAD KALKFONTEIN OOST FONTAINE BLEAU MARTINA DORASDEEL BERDINA PANORAMA YVONNE THE MONASTERY JOHN'S LOCKS VERDRIET SPIJT FONTEIN Kimberley SP ROOIFONTEIN OLIFANTSDAM HELPMEKAAR MIMOSA DEALESRUST WOLFPAN ZWARTLAAGTE MORNING STAR PLOOYSBURG BRAKDAM VAALPAN INHOEK CHOE RIETPAN Soetdoring R30 MARIA ATHELOON WATERVAL RUSOORD R709 LOUISLOOTE LAURA DE BAD STOFPUT OPSTAL HERMITAGE WOLVENFONTEIN SUNNYSIDE EERLIJK DORISVILLE ST ZUUR FONTEIN Verkeerdevlei ST LYONSREST R708 UITVAL SANCTUARY SUSANNA BOTHASDAM MERIBA AURORA KALKWAL ^!. VERKEERDEVLEI WATERVAL ZETLAND BELMONT ST SAPS SPITS KOP DIDIMALA LEMOENHOEK WATERVAL ORANGIA SCHOONVLAKTE DWAALHOEK WELTEVREDE GERTJE PAARDEBERG KOPPIES' N8 SANDDAM ZAMENKOMST R64 Nature DIEPHOEK FARMS KARREE KLIMOP MELKVLEY OMDRAAI Mantsopa NU ELYSIUM UMPUKANE HORATIO EUREKA ROODE PAN LK KAMEELPAN KOEDOE`S RAND KLIPFONTEIN DUIKERSDRAAI VLAKLAAGTE ST MIMOSA FAIRFIELD VALAF BEGINSEL Verkeerdevlei SP KOPPIESDAM MELIEFE ZAAIPLAATS PAARDEBERG KARREE DAM ARBEIDSGENOT DOORNLAAGTE EUREKA GELYK TAFELKOP KAREEKOP BOESMANSKOP AHLEN BLAUWKRANS VAN LOVEDALE ALETTA ROODE ESKOL "A" Tokologo NU AANKOMST -

Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District Socio�Economic Profile 2007 NO 1 and Development Plans

Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile 2007 NO 1 and development plans Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile and development plans Centre for Development Support (IB 100) University of the Free State PO Box 339 Bloemfontein 9300 South Africa www.ufs.ac.za/cds Please reference as: Centre for Development Support (CDS). 2007. Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile and development plans. CDS Research Report, Arid Areas, 2007(1). Bloemfontein: University of the Free State (UFS). CONTENTS I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 II. Geographic overview ........................................................................................................ 2 1. Namaqualand and Richtersveld ................................................................................................... 3 2. The Karoo................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Gordonia, the Kalahari and Bushmanland .................................................................................... 4 4. General characteristics of the arid areas ....................................................................................... 5 III. The Western Zone (Succulent Karoo) .............................................................................. 8 1. Namakwa District Municipality .................................................................................................. -

Appointment of Sheriffs

STAATSKOERANT, 7 MAART 2014 No. 37419 3 GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 167 OF 2014 the doj & cd Department: Justice and Constitutional Development REPUBUC OF SOUTH AFRICA 27 February 2014 APPOINTMENT OF SHERIFFS I, John Jeffrey, Deputy Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development as the duly delegated authority hereby, under section 2 of the Sheriff's Act, 1986 (Act No. 90 of 1986), appoint the persons listed in the accompanying Schedule as sheriffs in vacant offices corresponding to their names. The appointments take effect on 1 June 2014 or any other date as may be arrangedbetweentheDepartmentofJusticeandConstitutional Development and the persons I have so appointed as sheriffs. The details of the appointed sheriffs including their contact details and business addresses will be published on the website of the South African Board for Sheriffs (www.sheriffs.org.za) as well as that of the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (www.doj.gov.za) before the commencement date of the said appointments. Enquiries in this regard may be made at the South African Board for Sheriffs at the following contact telephone number: 021 426 0577. Given under my Hand at Pretoria on this the 27th day of February 2014. Mr J Jeffery, MP DEPUTY MINISTER OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 4 No. 37419 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 7 MARCH 2014 SCHEDULE EASTERN CAPE NO. APPOINTED PERSON VACANT OFFICE 1 Ms Babalwa Primrose Konjwa Molteno & Sterkstroom High and Lower Courts 2 Mr Luvuyo Jeffrey Leshosi Somerset East Lower Court (will be vacant with effect from 1 July 2014) FREE STATE NO. -

Executive Summary-Final-MRDP 20.03.04

RURAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020/2025 MANGUANG METRO MUNICIPALITY Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Mangaung Metro Rural Development Plan Page i Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ....................................................................................... 1 1.1 PREAMBLE .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 PURPOSE AND OBJECTVES OF THE RURAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN .......................................... 2 1.3 STUDY AREA OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................ 3 1.4 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 4 2. CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS............................................................................................................. 5 2.1 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK ........................................................................................................ 5 2.1.1 Policy Alignment ....................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.2 Policy Drivers .............................................................................................................................. 5 2.2 TOWARDS A VISION AND OBJECTIVES .................................................................................... 8 2.2.1 Vision Formulation .................................................................................................................... -

FS Sub Jan 2017 M-Wepener.Pdf

# # !C # # ### !C^# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # #!C# # # # !C# ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # ## !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # #!C # !C # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # ## # # # # # # # # # !C# # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # !C# !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ## # ##^ # !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # ## # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # # !C # !C # # # # !C# # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # !C # #!C # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ### !C # # # # !C !C# # ## # # # ## !C !C #!. # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C# # # # ## # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### #^ # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # ^ !C# # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # # ## # # !C ## !C## # # # # ## # !C # ## !C# ## # # ## # !C # # ^ # !C ## # # # !C# ^# # # !C # # # !C ## #!C ## # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C## ## # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # ## ## # # # # !C # # # # # !C ^ # # ## # # # # !. # # # # # # !C # !C# ### # # # # # #