Journal of Architectural Education Fall Editorial Board Meeting Portland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program of Exhibitions, and Architecture, in Collaboration with the Irwin S

ABOUT CLOSED WORLDS: STOREFRONT ENCOUNTERS THAT NEVER HAPPENED Storefront for Art and Architecture is committed to the advancement of innovative and critical positions at the intersection of architecture, art, Organized by Lydia Kallipoliti and Storefront for Art and design. Storefront’s program of exhibitions, and Architecture, in collaboration with The Irwin S. events, competitions, publications, and projects Chanin School of Architecture of The Cooper Union. provides an alternative platform for dialogue and collaboration across disciplinary, geographic and CLOSED WORLDS EXHIBITION ideological boundaries. Through physical and digital Curator and Principal Researcher: platforms, Storefront provides an open forum for Lydia Kallipoliti experiments that impact the understanding and Research: future of cities, urban territories, and public life. Alyssa Goraieb, Hamza Hasan, Tiffany Montanez, Since its founding in 1982, Storefront has presented Catherine Walker, Royd Zhang, Miguel Lantigua-Inoa, the work of over one thousand architects and artists. Emily Estes, Danielle Griffo and Chendru Starkloff Graphic Design and Exhibition Design: Storefront is a membership organization. If you would Pentagram / Natasha Jen like more information on our membership program with JangHyun Han and Melodie Yashar and benefits, please visit www.storefrontnews.org/ Feedback Drawings: membership. Tope Olujobi Lexicon Editor: For more information about upcoming events and Hamza Hasan projects, or to learn about ways to get involved with Special Thanks: Storefront, -

Download This Issue As A

MICHAEL GERRARD ‘72 COLLEGE HONORS FIVE IS THE GURU OF DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI CLIMATE CHANGE LAW WITH JOHN JAY AWARDS Page 26 Page 18 Columbia College May/June 2011 TODAY Nobel Prize-winner Martin Chalfie works with College students in his laboratory. APassion for Science Members of the College’s science community discuss their groundbreaking research ’ll meet you for a I drink at the club...” Meet. Dine. Play. Take a seat at the newly renovated bar grill or fine dining room. See how membership in the Columbia Club could fit into your life. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 26 20 30 18 73 16 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 2 20 A PA SSION FOR SCIENCE 38 B OOKSHELF LETTERS TO THE Members of the College’s scientific community share Featured: N.C. Christopher EDITOR Couch ’76 takes a serious look their groundbreaking work; also, a look at “Frontiers at The Joker and his creator in 3 WITHIN THE FA MILY of Science,” the Core’s newest component. Jerry Robinson: Ambassador of By Ethan Rouen ’04J, ’11 Business Comics. 4 AROUND THE QU A DS 4 Reunion, Dean’s FEATURES 40 O BITU A RIES Day 2011 6 Class Day, 43 C L A SS NOTES JOHN JA Y AW A RDS DINNER FETES FIVE Commencement 2011 18 The College honored five alumni for their distinguished A LUMNI PROFILES 8 Senate Votes on ROTC professional achievements at a gala dinner in March. -

The Blue &White

THE UNDERGRADUATE MAGAZINE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, EST. 1890 THE BLUE & WHITE Vol. XVIII No. II April 2012 SIGNIFICANT OTHER Comparing the Core Curricula of Columbia and University of Chicago GROUP DYNAMICS Dissonance Within the A Capella Community ALSO INSIDE: WHAT’S IN A NAME? BRIAN WAGNER, SEAS ’13, Editor-in-Chief ZUZANA GIERTLOVA, BC ’14, Publisher SYLVIE KREKOW, BC ’13, Managing Editor MARK HAY, CC ’12, Editor Emeritus LIZ NAIDEN, CC ’12, Editor Emerita CONOR SKELDING, CC ’14, Culture Editor AMALIA SCOTT, CC ’13, Literary Editor SANJANA MALHOTRA, CC ’15, Layout Editor CINDY PAN, CC ’12, Graphics Editor LIZ LEE, CC ’12, Senior Illustrator ANNA BAHR, BC ’14, Senior Editor ALLIE CURRY, CC ’13, Senior Editor CLAIRE SABEL, CC ’13, Senior Editor Contributors Artists ALEXANDRA AVVOCATO, CC ’15 ASHLEY CHIN, CC ’12 BRIT BYRD, CC ’15 CELIA COOPER, CC ’15 CLAVA BRODSKY, CC ’13 MANUEL CORDERO, CC ’14 AUGUSTA HARRIS, BC ’15 SEVAN GATSBY, BC ’12 TUCKES KUMAN, CC’13 LILY KEANE, BC ’13 BRIANA LAST, CC ’14 MADDY KLOSS, CC ’12 ALEXANDRA SVOKOS, CC ’14 EMILY LAZERWITZ, CC ’14 ERICA WEAVER, CC ’12 LOUISE MCCUNE, CC ’13 VICTORIA WILLS, CC ’14 CHANTAL MCSTAY, CC ’15 ELOISE OWENS, BC ’12 Copy Editor EDUARDO SANTANA, CC ’13 HANNAH FORD, CC ’13 CHANTAL STEIN, CC ’13 JULIA STERN, BC ’14 ADELA YAWITZ, CC ’12 THE BLUE & WHITE Vol. XVIII FAMAM EXTENDIMUS FACTIS No. II COLUMNS 4 BLUEBOOK 6 BLUE NOTES 8 CAMPUS CHARACTERS 12 VERILY VERITAS 24 MEASURE FOR MEASURE 30 DIGITALIA COLUMbiANA 31 CAMPUS GOSSIP FEATURES Victoria Wills & Mark Hay 10 AT TWO SWORDS’ LENGTH: SHOULD YOU GET OFF AT 116TH? Our Monthly Prose and Cons. -

Le Havre, La Ville Reconstruite Par Auguste Perret

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1181.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Le Havre, the city rebuilt by Auguste Perret DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 15th July 2005 STATE PARTY: FRANCE CRITERIA: C (ii)(iv) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Decisions of the 29th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (ii): The post-war reconstruction plan of Le Havre is an outstanding example and a landmark of the integration of urban planning traditions and a pioneer implementation of modern developments in architecture, technology, and town planning. Criterion (iv): Le Havre is an outstanding post-war example of urban planning and architecture based on the unity of methodology and system of prefabrication, the systematic use of a modular grid and the innovative exploitation of the potential of concrete. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS The city of Le Havre, on the English Channel in Normandy, was severely bombed during the Second World War. The destroyed area was rebuilt according to the plan of a team headed by Auguste Perret, from 1945 to 1964. The site forms the administrative, commercial and cultural centre of Le Havre. Amongst many reconstructed cities, Le Havre is exceptional for its unity and integrity. It combines a reflection of the earlier pattern of the town and its extant historic structures with the new ideas of town planning and construction technology. It is an outstanding post-war example of urban planning and architecture based on the unity of methodology and the use of prefabrication, the systematic utilization of a modular grid, and the innovative exploitation of the potential of concrete. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

THE BLUE and WHITE Voe VI, No

, THE BLUE AND WHITE VoE VI, No. IV Aprii 2000 Columbia College, New York N Y Look closer... "A V' \ v ' \ V \ \ • \ V K CULINARY HUM ANITIES: A proposal by M a riel L. W olf son AREA STUDIES DEFENDED II THE LAST DAYS OF RIVER by Prof. Mark von Hagen A Conversation BARNARD SWIPE ACCESS TOLD BETWEEN PUFFS, FROM RUSSIA Blue J. Verily Veritas About the Cover: “Columbia Beauty” by Katerina A. Barry. m« € g é > C O L II M B 1 A J ^ copyexpress Copies Made Easy 5p Self-Service Copies • Color Copies 3 Convenient Campus • Evening Hours Locations • Offset Printing Services 301 W Lerner Hall 106 Journalism 400 IAB (next to computer center) (lower level) 854-3797 Phone 854-0170 Phone 854-3233 Phone 864-2728 Fax 854-0173 Fax 222-0193 Fax Hours Hours Hours 8am - 11pm M -Th 9am - 5pm M - F 8:30am - 8pm M - Th 8am - 9 pm Fri 8:30am - 5pm Fri 11am - 6pm Sat 12pm - 11pm Sun Admit it. You LOVE making copies. THE BLUE AND WHITE V o l. VI New York, April 2000 No. IV THE BLUE AND WHITE This number of The Blue and White proposes quite a bit of change in the way we do busi ness around here. But as the oldest magazine Editor-in-Chief on campus, we’re also believers in institution MATTHEW RASCOFF, C’01 al memory. Hilary E. Feldstein argues against Publisher Professor Mark von Hagen’s proposal, and in C. ALEXANDER LONDON, C’02 favor is the traditional departmental division Managing Editor o f academic labor. -

AMS Newsletter February 2014

AMS NEWSLETTER THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY CONSTITUENT MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN COUNCIL OF LEARNED SOCIETIES VOLUME XLIV, NUMBER 1 February 2014 ISSN 0402-012X AMS Milwaukee 2014: Not Just 2013 Annual Beer, Brats, and Cheese Meeting: Pittsburgh AMS Milwaukee 2014 venues right in the downtown area, includ- The seventy-ninth Annual Meeting of the 6–9 November ing the Marcus Center for the Performing American Musicological Society took place www.ams-net.org/milwaukee Arts, home of the Milwaukee Symphony, the 7–10 November among the bridges, rivers, Florentine Opera, and the Milwaukee Bal- and hills of Pittsburgh’s Golden Triangle. Members of the AMS and the SMT will let. Pabst Theatre and the nearby Riverside The program was packed to the gills, with converge on Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in No- Theatre are home to regular series and the an average of seven concurrent scholarly ses- vember for their annual meetings. Situated Milwaukee Repertory Company. The large sions plus numerous meetings by the Soci- on the west shore of Lake Michigan about Milwaukee Theatre hosts roadshows. The ety’s committees, study groups, and editorial ninety miles north of Chicago, Milwaukee is downtown also boasts two arenas hosting boards, as well as lectures and recitals select- known as the Cream City not because Wis- sporting events and touring acts. The Broad- ed by the Performance Committee. Papers consin is America’s Dairyland, but because way Theatre presents smaller events, includ- and sessions spanned the entire range of the of the ubiquity of cream-colored brick used ing local theater companies and the Skylight field, from the origins of Christian chant to in the city’s oldest buildings. -

Theorie De L'architecture

COURS 08 -sem 6 -UE1 17 mai 2006 COURS INAUGURAL SÉRIE 1 : « enquêtes » (Philippe Villien) 1,1 - ARNE JACOBSEN - ACIER - L’ESCALIER DE LA MAIRIE DE RODOVRE 1,2 - CARLO SCARPA - BÉTON - LE CIMETIÈRE BRION-VEGA À SAN VITO D’ALTIVOLE 1,3 - PETER ZUMTHOR - PIERRE - LES THERMES DE VALS 1,4 - SWERE FEHN - BOIS - MAISONS SÉRIE 2 : « paysage et édifice» (Dominique Hernandez) 2,1 - CULTURE DU REGARD (limites, seuils, topographie) 2,2 - LE PAYSAGE ENVELOPPE DE L’EDIFICE (composition dedans - dehors) 2,3 - LES TEMPS DU VIVANT (orientation, lumières, végétal) SÉRIE 3 : « représenter le concept » (Philippe Villien et Delphine Desert) 3,1 - LES OUTILS DE LA CONCEPTION ARCHITECTURALE 3,2 - DIFFUSION D’UNE PENSEE THEORIQUE : REM KOOLHAAS Ecole d’architecture de Paris-Belleville_cycle Licence_3e année_2e semestre THEORIE DE L’ARCHITECTURE Représenter le concept D elphine D E S E R T 2006 Ecole d’architecture de Paris-Belleville_cycle Licence_3e année_2e semestre THEORIE DE L’ARCHITECTURE R e p rése nter le concept 2re partie Diffusion d’une pensée théorique Ecole d’architecture de Paris-Belleville_cycle Licence_3e année_2e semestre R e présenter le co n cept Diffusion d’une pensée théorique Sommaire Ecole d’architecture de Paris-Belleville_cycle Licence_3e année_2e semestre L e s outils de la représentation sommaire 1. Prése ntation des acteurs • Re m Koolhaas • OMA • OMA/AMO • Réalisations pleïomorphes 2. Image et com m u nication • Communication du projet • Le discours • L'écriture • L’image 3. Approches théoriques Koolhaassienne • « Paranoiac Critical -

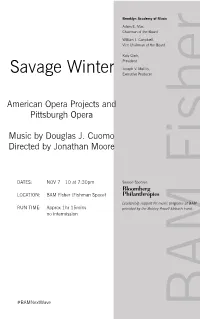

Savage Winter #Bamnextwave No Intermission LOCATION: RUN TIME: DATES: Pittsburgh Opera Approx 1Hr15mins BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) NOV 7—10At7:30Pm

Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Savage Winter Executive Producer American Opera Projects and Pittsburgh Opera Music by Douglas J. Cuomo Directed by Jonathan Moore DATES: NOV 7—10 at 7:30pm Season Sponsor: LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) Leadership support for music programs at BAM RUN TIME: Approx 1hr 15mins provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund. no intermission #BAMNextWave BAM Fisher Savage Winter Written and Composed by Music Director This project is supported in part by an Douglas J. Cuomo Alan Johnson award from the National Endowment for the Arts, and funding from The Andrew Text based on the poem Winterreise by Production Manager W. Mellon Foundation. Significant project Wilhelm Müller Robert Signom III support was provided by the following: Ms. Michele Fabrizi, Dr. Freddie and Directed by Production Coordinator Hilda Fu, The James E. and Sharon C. Jonathan Moore Scott H. Schneider Rohr Foundation, Steve & Gail Mosites, David & Gabriela Porges, Fund for New Performers Technical Director and Innovative Programming and The Protagonist: Tony Boutté (tenor) Sean E. West Productions, Dr. Lisa Cibik and Bernie Guitar/Electronics: Douglas J. Cuomo Kobosky, Michele & Pat Atkins, James Conductor/Piano: Alan Johnson Stage Manager & Judith Matheny, Diana Reid & Marc Trumpet: Sir Frank London Melissa Robilotta Chazaud, Francois Bitz, Mr. & Mrs. John E. Traina, Mr. & Mrs. Demetrios Patrinos, Scenery and properties design Assistant Director Heinz Endowments, R.K. Mellon Brandon McNeel Liz Power Foundation, Mr. & Mrs. William F. Benter, Amy & David Michaliszyn, The Estate of Video design Assistant Stage Manager Jane E. -

![Architecture of Museums : [Exhibition], Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 24-November 11, 1968](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7940/architecture-of-museums-exhibition-museum-of-modern-art-new-york-september-24-november-11-1968-627940.webp)

Architecture of Museums : [Exhibition], Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 24-November 11, 1968

Architecture of museums : [exhibition], Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 24-November 11, 1968 Date 1968 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2612 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art Architecture of Museums The Museum of Modern Art, New York. September 24 —November 11, 1968 LIBRARY Museumof ModernArt ^9 Architecture of Museums The "musee imaginaire" assembled by Andre Malraux from mankind's universal reservoir of art has an architectural complement. It is the imaginary museum that has existed in the ideas and designs of architects for two centuries, ever since the museum's inception as a public institution. A giftto modern democracies, museums have remained, through the vicissitudes of their history, one of the few unanimously accepted inventions of the age of enlightenment. The revolutionary minds of the eighteenth century saw in the idea of the museum a worthy successor to the churches they sought to abolish. The museum the French architect Etienne Boullee projected in 1783, with a "temple of fame for statues of great men" at its center, is in idea and form a secular pantheon. Indeed, that Roman monument became as much the prototype for the interiors of classicists' museums as did Greek temple fronts for their otherwise plain exteriors. During the nineteenth century, while the domed halls still symbolized the universal patrimony of art, the accumulation of treasure within became a matter of patriotic pride. -

BRASILIA – CHANDIGARH – LE HAVRE PORTRAITS DE VILLES Du 2 Juin Au 16 Septembre 2007

MUSÉE MALRAUX LE HAVRE BRASILIA – CHANDIGARH – LE HAVRE PORTRAITS DE VILLES du 2 juin au 16 septembre 2007 ATTACHÉE DE PRESSE Catherine Bertrand Tél. 02 35 19 44 21 Fax 02 35 19 47 41 [email protected] SOMMAIRE Communiqué de l’exposition ....................................................... pages 2-5 Colloque international en septembre 2007 au Havre .................................. page 6 Brasilia (histoire et construction) ................................................... pages 7-8 Chandigarh (histoire et construction) ............................................. pages 9-10 Le Havre (histoire et construction) ............................................... pages 11-12 Liste des œuvres exposées ........................................................ pages 13-16 Renseignements pratiques ........................................................... page 17 Catalogue de l’exposition ............................................................ page 17 BRASILIA – CHANDIGARH – LE HAVRE / PORTRAITS DE VILLES 1 MUSÉE MALRAUX – LE HAVRE BRASILIA – CHANDIGARH – LE HAVRE PORTRAITS DE VILLES du 2 juin au 16 septembre 2007 Exposition d’œuvres Le 15 juillet 2005, le bureau du Patrimoine de l’UNESCO décidait à l’unanimité l’inscrip- photographiques et vidéos tion, au Patrimoine mondial de l’Humanité, du centre-ville du Havre reconstruit par au musée Malraux, Le Havre, Auguste Perret. du 2 juin au 16 septembre 2007. Depuis lors, la Ville du Havre a engagé un programme d’actions visant à valoriser ce label. Un colloque international sera organisé dans ce cadre les jeudi 13 et vendredi 14 sep- LUCIEN HERVÉ tembre 2007, autour du thème « Brasilia – Chandigarh – Le Havre – Tel Aviv. Quatre villes LOUIDGI BELTRAME symboles du XXe siècle ». EMMANUELLE BLANC JORDI COLOMER Parallèlement, et en amont de cette manifestation, le musée Malraux présentera à partir STÉPHANE COUTURIER du samedi 2 juin prochain une exposition de photos : « Brasilia – Chandigarh – Le Havre. GEORGE DUPIN VÉRONIQUE ELLÉNA Portraits de villes ». -

LH Groupe Scolaire Paul Bert

Fichier international de DoCoMoMo _________________________________________________________________ 1. IDENTITÉ DU BÂTIMENT OU DU GROUPE DE BÂTIMENTS nom usuel du bâtiment : Groupe scolaire Paul Bert variante : numéro et nom de la rue : 65 avenue Paul Bert (école maternelle), 49-51 rue des Iris (école élémentaire), Aplemont ville : Le Havre pays : France ................................................................................................................................... PROPRIÉTAIRE ACTUEL nom : Ville du Havre adresse : téléphone : 02 35 47 12 62 (école maternelle) et 02 35 47 24 23 (école élémentaire) fax : ................................................................................................................................... ÉTAT DE LA PROTECTION type : date : ................................................................................................................................... ORGANISME RESPONSABLE DE LA PROTECTION nom : adresse : téléphone : fax : ................................................................................................................................... 2. HISTOIRE DU BATIMENT commande : Vingt-cinq écoles de l’agglomération havraise ont été détruites par les bombardements de septembre 1944, dont l’ancien groupe Paul Bert. Construit dans les années 1930 au sein d’une cité- jardins, il comprenait une école de garçons de douze classes, une de filles de douze classes et un jardin d’enfants de cinq classes. D’architecture moderne, son ossature était en béton et son habillage en