Pathways for Peace & Stability in Taiz, Yemen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Participation in the Arab Uprisings: a Struggle for Justice

Distr. LIMITED E/ESCWA/SDD/2013/Technical Paper.13 26 December 2013 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA (ESCWA) WOMEN AND PARTICIPATION IN THE ARAB UPRISINGS: A STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE New York, 2013 13-0381 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper constitutes part of the research conducted by the Social Participatory Development Section within the Social Development Division to advocate the principles of social justice, participation and citizenship. Specifically, the paper discusses the pivotal role of women in the democratic movements that swept the region three years ago and the challenges they faced in the process. The paper argues that the increased participation of women and their commendable struggle against gender-based injustices have not yet translated into greater freedoms or increased political participation. More critically, in a region dominated by a patriarchal mindset, violence against women has become a means to an end and a tool to exercise control over society. If the demands for bread, freedom and social justice are not linked to discourses aimed at achieving gender justice, the goals of the Arab revolutions will remain elusive. This paper was co-authored by Ms. Dina Tannir, Social Affairs Officer, and Ms. Vivienne Badaan, Research Assistant, and has benefited from the overall guidance and comments of Ms. Maha Yahya, Chief, Social Participatory Development Section. iii iv CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... iii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. GENDERING ARAB REVOLUTIONS: WHAT WOMEN WANT ......................... 2 A. The centrality of gender to Arab revolutions............................................................ 2 B. Participation par excellence: Activism among Arab women.................................... 3 III. CHANGING LANES: THE STRUGGLE OVER WOMEN’S BODIES ................. -

Yemen Sheila Carapico University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Political Science Faculty Publications Political Science 2013 Yemen Sheila Carapico University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Carapico, Sheila. "Yemen." In Dispatches from the Arab Spring: Understanding the New Middle East, edited by Paul Amar and Vijay Prashad, 101-121. New Delhi, India: LeftWord Books, 2013. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yemen SHEILA CARAPICO IN FEBRUARY 2011, Tawakkol Karman stood on a stage outside Sanaa University. A microphone in one hand and the other clenched defiantly above her head, reading from a list of demands, she led tens of thou sands of cheering, flag-waving demonstrators in calls for peaceful politi cal change. She was to become not so much the leader as the figurehead ofYemen's uprising. On other days and in other cities, other citizens led the chants: men and women and sometimes, for effect, little children. These mass public performances enacted a veritable civic revolution in a poverty-stricken country where previous activist surges never produced democratic transitions but nonetheless did shape national history. Drawing on the Tunisiari and Egyptian inspirations as well as homegrown protest legacies, in 2011 Yemenis occupied the national commons as never before. -

Summary of the Evaluation I

Summary of the Evaluation I. Outline of the Project Project Title: Broadening Regional Initiative for Country: Yemen Developing Girls’ Education (BRIDGE) Program in Taiz Governorate Cooperation Scheme: Technology Cooperation Sector: Basic Education Project Basic Education Team I, Group I Total cost (as of the time of evaluation): 4.5 billion Division in (Basic Education), Human Japanese yen Charge: Development Department Implementing organization in Yemen: Taiz Governorate Education Office (R/D) 23 March 2005 Organization in Japan: JICA Cooperation Related Cooperation: School Construction in Taiz, Three years and five months Period Ibb and Sanaa (Grant Aid), Classroom renovation in (2005.6.22–2008.11.30) Taiz (Grassroots Grant Aid) 1-1 Background of the Project The Government of Yemen has considered that education is fundamental to its development. In 2003, the Ministry of Education (MOE) developed its Basic Education Development Strategy (BEDS) for 2003-2015, and has been carrying out the promotion of girls’ education as one of vital policies of education in Yemen. Along this line, the Government of Yemen and the Government of Japan agreed to implement the BRIDGE Project on 23 March 2005. The Project started in June 2005 and will be completed in the end of November 2008. 1-2 Project Overview (1) Overall Goal Girls’ access to basic education in Taiz Governorate is increased. (2) Project Purpose The effective model of regional educational administration based on community participating and school initiatives is developed for improving girls’ access to educational opportunities in the targeted districts in Taiz Governorate. (3) Outputs of the Project Output 1 Taiz Governorate’s capacity on regional educational administration is enhanced. -

How the Ongoing Crisis in Taiz Governorate Continues to Put Civilians at Risk

A crisis with no end in sight How the ongoing crisis in Taiz Governorate continues to put civilians at risk www.oxfam.org OXFAM BRIEFING NOTE – DECEMBER 2020 Despite a UN-brokered peace agreement in December 2018, the conflict in Yemen has run into its sixth year. In Taiz Governorate, civilians continue to bear the brunt of conflict. Every day, they face death or injury from indiscriminate attacks, gender- based violence in their homes and poor access to food, water and medical care. As people’s resources are further exhausted, their safety, security and well-being are only likely to worsen. The COVID-19 pandemic has added an additional layer to the ongoing crisis. The people of Taiz – and across Yemen as a whole – desperately need a lasting and inclusive peace process to end the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. © Oxfam International December 2020 This paper was written by Abdulwasea Mohammed, with support from Hannah Cooper. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Amr Mohammed, Georges Ghali, Helen Bunting, Martin Butcher, Nabeel Alkhaiaty, Omar Algunaid, Marina Di Lauro, Ricardo Fal-Dutra Santos, Ruth James and Tom Fuller in its production. Particular thanks go to the organizations and individuals that Oxfam spoke with as part of the research for this briefing note. It is part of a series of papers written to inform public debate on development and humanitarian policy issues. For further information on the issues raised in this paper please email [email protected] This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. -

Yemen's National Dialogue

arab uprisings Yemen’s National Dialogue March 21, 2013 MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY MOHAMMED POMEPS Briefings 19 Contents Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue . 5 Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen . 7 Can Yemen be a Nation United? . 10 Yemen’s Southern Intifada . 13 Best Friends Forever for Yemen’s Revolutionaries? . 18 A Shake Up in Yemen’s GPC? . 21 Hot Pants: A Visit to Ousted Yemeni Leader Ali Abdullah Saleh’s New Presidential Museum . .. 23 Triage for a fracturing Yemen . 26 Building a Yemeni state while losing a nation . 32 Yemen’s Rocky Roadmap . 35 Don’t call Yemen a “failed state” . 38 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/03/18/overcoming_the_pitfalls_of_yemen_s_national_dialogue Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/02/22/consolidating_uncertainty_in_yemen -

And the Qatari Dreams 00 Starts from Al-Hajriya of Taiz

Cover Title The Islah Party , The Yemen Vatican 00 (The Brothers') Rule inside The State !!! And the Qatari Dreams 00 Starts from Al-Hajriya of Taiz 1 The Title of the Report: Haq Organization's report : Taiz Governorate outside the state control . Al-Islah Party changed it into brother Emirate and into non-organized camps. For the armed bodies and terrorist's organizations funded by Qatar. 2 Field report Taiz Governorate Taiz Governorate outside the sovereignty of the state. The Content of the Report The content page No. Acknowledgment 4 Background 5 Taiz Governorate outside the sovereignty of 7 the state Destroying the last strongholds of state 20 Irregular training camps 32 Serious crimes according to Intel Law 47 Recommendations 64 Efforts and activities of the organization and access to international forums: The organization has made efforts and activities for 10 years, through which it has been keen on continuous work in monitoring the human rights situation, documenting it in accordance with international standards, preparing reports and publishing them before various media outlets and public opinion, and delivering them to the concerned authorities locally and internationally. We review the efforts of the organization through its field work in monitoring and following up the reality of human rights in Taiz Governorate five years ago, as the organization produced a number of field reports related to violations and serious crimes against human rights in Taiz governorate, namely: 1. The reality of human rights and informal prisons (October 2017) 2. Legitimate prisons and illegal prisons (January 2019) 3. The dangers of sectarianism and storming the old city ...... -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Arab Spring Abroad

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Arab Spring Abroad: Mobilization among Syrian, Libyan, and Yemeni Diasporas in the U.S. and Great Britain DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Sociology by Dana M. Moss Dissertation Committee: Distinguished Professor David A. Snow, Chair Chancellor’s Professor Charles Ragin Professor Judith Stepan-Norris Professor David S. Meyer Associate Professor Yang Su 2016 © 2016 Dana M. Moss DEDICATION To my husband William Picard, an exceptional partner and a true activist; and to my wonderfully supportive and loving parents, Nancy Watts and John Moss. Thank you for everything, always. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ACRONYMS iv LIST OF FIGURES v LIST OF TABLES vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii CURRICULUM VITAE viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xiv INTRODUCTION 1 PART I: THE DYNAMICS OF DIASPORA MOVEMENT EMERGENCE CHAPTER 1: Diaspora Activism before the Arab Spring 30 CHAPTER 2: The Resurgence and Emergence of Transnational Diaspora Mobilization during the Arab Spring 70 PART II: THE ROLES OF THE DIASPORAS IN THE REVOLUTIONS 126 CHAPTER 3: The Libyan Case 132 CHAPTER 4: The Syrian Case 169 CHAPTER 5: The Yemeni Case 219 PART III: SHORT-TERM OUTCOMES OF THE ARAB SPRING CHAPTER 6: The Effects of Episodic Transnational Mobilization on Diaspora Politics 247 CHAPTER 7: Conclusion and Implications 270 REFERENCES 283 ENDNOTES 292 iii LIST OF ACRONYMS FSA Free Syria Army ISIS The Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham, or Daesh NFSL National Front for the Salvation -

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background the Yemen Civil War Is

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background The Yemen civil war is currently in its fifth year, but tensions within the country have existed for many years. The conflict in Yemen has been labelled as the worst humanitarian crisis in the world by the United Nations (UN) and is categorized as a man-made phenomenon. According to the UN, 80% of the population of Yemen need humanitarian assistance, with 2/3 of its population considered to be food insecure while 1/3 of its population is suffering from extreme levels of hunger and most districts in Yemen at risk of famine. As the conditions in Yemen continue to deteriorate, the world’s largest cholera outbreak occurred in Yemen in 2017 with a reported one million infected.1 Prior to the conflict itself, Yemen has been among the poorest countries in the Arab Peninsula. However, that is contradictory considering the natural resources that Yemen possess, such as minerals and oil, and its strategical location of being adjacent to the Red Sea.2 Yemen has a large natural reserve of natural gasses and minerals, with over 490 billion cubic meters as of 2010. These minerals include the likes of silver, gold, zinc, cobalt and nickel. The conflict in Yemen is a result of a civil war between the Houthi, with the help of Former President Saleh, and the Yemen government that is represented by 1 UNOCHA. “Yemen.” Humanitarian Needs Overview 2019, 2019. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2019_Yemen_HNO_FINAL.pdf. 2 Sophy Owuor, “What Are The Major Natural Resources Of Yemen?” WorldAtlas, February 19, 2019. -

Institutional Change and the Egyptian Presence in Yemen 1962-19671

1 Importing the Revolution: Institutional change and the Egyptian presence in Yemen 1962-19671 Joshua Rogers Accepted version. Published 2018 in Marc Owen Jones, Ross Porter and Marc Valeri (eds.): Gulfization of the Arab World. Berlin, London: Gerlach, pp. 113-133. Abstract Between 1962 and 1967, Egypt launched a large-scale military intervention to support the government of the newly formed Yemen Arab Republic. Some 70,000 Egyptian military personnel and hundreds of civilian advisors were deployed with the stated aim to ‘modernize Yemeni institutions’ and ‘bring Yemen out of the Middle Ages.’ This article tells the story of this significant top-down and externally-driven transformation, focusing on changes in the military and formal government administration in the Yemen Arab Republic and drawing on hitherto unavailable Egyptian archival material. Highlighting both the significant ambiguity in the Egyptian state-building project itself, as well as the unintended consequences that ensued as Egyptian plans collided with existing power structures; it traces the impact of Egyptian intervention on new state institutions, their modes of functioning, and the articulation of these ‘modern’ institutions, particularly the military and new central ministries, with established tribal and village-based power structures. 1. Introduction On the night of 26 September 1962, a column of T-34 tanks trundled through the streets of Sana‗a and surrounded the palace of the new Imam of Yemen, Mu ammad al-Badr,2 who had succeeded his father Imam ‘ mad (r.1948-62) only one week earlier. Opening fire shortly before midnight, the Yemeni Free Officers announced the ‗26 September Revolution‘ on Radio Sana‗a and declared the formation of a new state: the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR). -

Parasitological and Biochemical Studies on Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Shara'b District, Taiz, Yemen

Asmaa et al. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob (2017) 16:47 DOI 10.1186/s12941-017-0224-y Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials RESEARCH Open Access Parasitological and biochemical studies on cutaneous leishmaniasis in Shara’b District, Taiz, Yemen Qhtan Asmaa1, Salwa AL‑Shamerii2, Mohammed Al‑Tag3, Adam AL‑Shamerii4, Yiping Li1* and Bashir H. Osman5 Abstract Background: The leishmaniasis is a group of diseases caused by intracellular haemofagellate protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania. Leishmaniasis has diverse clinical manifestations; cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is the most com‑ mon form of leishmaniasis which is responsible for 60% of disability-adjusted life years. CL is endemic in Yemen. In Shara’b there is no reference study available to identify the prevalence of endemic diseases and no investigation has been conducted for diagnosing the diseases. Methods: This study was conducted in villages for CL which collected randomly. The study aimed at investigating the epidemiological factors of CL in Shara’b by using questioner. Symptoms of lesions in patients sufering from CL, confrmed by laboratory tests, gave a new evidence of biochemical diagnosis in 525 villagers aged between 1 and 60 years old. Venous bloods were collected from 99 patients as well as from 51 control after an overnight fast. Results: The percentage prevalence of CL was found 18.8%. The prevalence rate of infection among males (19.3%) was higher than females (18.40%). Younger age group (1–15) had a higher prevalence rate (20.3%) than the other age groups. Furthermore, the population with no formal education had the higher rate of infection (61% of the total). -

Egyptian Foreign Policy (Special Reference After the 25Th of January Revolution)

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE DERECHO INTERNACIONAL PÚBLICO Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES TESIS DOCTORAL Egyptian foreign policy (special reference after The 25th of January Revolution) MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTORA PRESENTADA POR Rania Ahmed Hemaid DIRECTOR Najib Abu-Warda Madrid, 2018 © Rania Ahmed Hemaid, 2017 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Políticas Y Socioligía Departamento de Derecho Internacional Público y Relaciones Internacionales Doctoral Program Political Sciences PHD dissertation Egyptian Foreign Policy (Special Reference after The 25th of January Revolution) POLÍTICA EXTERIOR EGIPCIA (ESPECIAL REFERENCIA DESPUÉS DE LA REVOLUCIÓN DEL 25 DE ENERO) Elaborated by Rania Ahmed Hemaid Under the Supervision of Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda Professor of International Relations in the Faculty of Information Sciences, Complutense University of Madrid Madrid, 2017 Ph.D. Dissertation Presented to the Complutense University of Madrid for obtaining the doctoral degree in Political Science by Ms. Rania Ahmed Hemaid, under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda Professor of International Relations, Faculty of Information Sciences, Complutense University of Madrid. University: Complutense University of Madrid. Department: International Public Law and International Relations (International Studies). Program: Doctorate in Political Science. Director: Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda. Academic Year: 2017 Madrid, 2017 DEDICATION Dedication To my dearest parents may god rest their souls in peace and to my only family my sister whom without her support and love I would not have conducted this piece of work ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda for the continuous support of my Ph.D. -

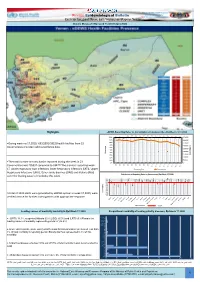

Eiectronic Integrated Disease Early Warning and Response System Volume 08,Lssue17,Epi Week 17,(20-26 April,2020)

Ministary Of Public Health Papulation Epidemiological Bulletin Primary Heath Care Sector Weekly DG for Diseases Control & Surveillance Eiectronic Integrated Disease Early Warning and Response System Volume 08,lssue17,Epi week 17,(20-26 April,2020) Highlights eDEWS Reporting Rates vs Consultations in Govemorates,Epi Weeks 1-17,2020 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % 97 97 97 95 % 96 96 96 96 95 95 95 95 100% 94 450000 96 96 92 96 90% 400000 •During week no.17,2020, %92(1991/1822) health facilites from 23 80% 350000 70% 300000 Governorates provided valid surveillance data. 60% 250000 50% 200000 Percentage 40% 150000 Consulttaions 30% 20% 100000 10% 50000 •The total number of consultation reported during the week in 23 0% 0 Wk 2 Wk Wk 1 Wk 3 Wk 4 Wk 5 Wk 6 Wk 7 Wk 8 Wk 9 Wk Wk 16 Wk Wk 11 Wk 12 Wk 13 Wk 14 Wk 15 Wk 17 Wk Governorates was 295637 compared to 334727 the previous reporting week 10 Wk 17. Acute respiratory tract infections lower Respiratory Infections (LRTI), Upper Reporting Rate Consultations Respiratory Infections (URTI), Other acute diarrhea (OAD) and Malaria (Mal) Distribution of Reporting Rates by Governoraes (Epi-Week 17,2020) were the leading cause of morbidity this week. % % % % % 100% % % % % % % % 95 % % % 97 98 100 90% 100 99 90 81 100 97 100 100 % 98 96 96 % % 80% % 88 % % 92 86 73 70% % % 77 74 60% 76 69 50% 40% 30% No. HF Reports 20% A total of 1332 alerts were generated by eDEWS system in week 17,2020, were 10% verified as true for further investigations with appropriate response 0% Reporting Rate Target Leading causes