Recurring Topoi: a Qualitative Study on Visual Attractions in Dutch Theme Park Efteling from a Media-Archaeological Point of View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

0500/11 Paper 1 Reading Passage (Core) May/June 2010 1 Hour 45 Minutes Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *1

www.XtremePapers.com UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL EXAMINATIONS International General Certificate of Secondary Education FIRST LANGUAGE ENGLISH 0500/11 Paper 1 Reading Passage (Core) May/June 2010 1 hour 45 minutes Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *1 79 READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST 2 997367 If you have been given an Answer Booklet, follow the instructions on the front cover of the Booklet. Write your Centre number, candidate number and name on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen. Do not use staples, paper clips, highlighters, glue or correction fluid. * Answer all questions. Dictionaries are not permitted. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. This document consists of 4 printed pages. DC (AC) 22609/2 © UCLES 2010 [Turn over 2 Read the following passage carefully, and then answer all the questions. Sheryl Garratt, her husband and five-year-old son Liam visit an eccentric Dutch theme park. Soon after arriving at the Dutch theme park, Efteling, we were in a boat on a man-made waterway which is pretty much as you’d expect of a trip to Holland. Apart from the camels and the crocodiles... Floating through the bazaar of the fictional Arabian town of Fata Morgana, we passed hordes of shoppers and beggars crowding the bazaar while a man screamed in agony as a robotic dentist 5 administered to him in an open-air surgery. Women in exotic dresses danced in the courtyards and prisoners groaned in the dungeons. -

Shows Und Live-Entertainment !.!# Thailändischer Tempel Mit Panoramablick

WEG ZUM R EFTELING2HOTEL MARERIJK RUIG IJK ! Sprookjesbos (Märchenwald) #! Kinderspoor Pedalbetriebener Tretzug. !.)! Dornröschen !.!% Tischlein deck dich, Esel streck dich !.)" Das Zwergendorf #" "& !.)* Die sechs Diener (Langhals) !.!& Schneewittchen Halve Maen !.)# Rotkäppchen !.!' Genovevas Brautkleid Riesen-Schiaschaukel. !.)$ Pinocchio !.!( Aschenputtel #* De Oude Tu?erbaan #$ !.)% Die roten Schuhe !.") Der Froschkönig H"& !.)& Der Trollkönig !."! Die magische Uhr Fahrt in einem Oldtimer. !.)' Die ungezogene Prinzessin !."" Die indischen Seerosen (sprechender Papagei) !."* Der kleine Däumling ## Polka Marina #* H#$ !.)( Rapunzel !."# Rumpelstilzchen Wellen-Karussell. !.!) Die kleine Meerjungfrau !."$ Das kleine Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern #$ Stoomtrein #! !.!! Der Drache H"$ !.!" Der Wolf und die sieben Geißlein !."% Des Kaisers neue Kleider Zugfahrt durch Efteling in einer echten Dampfeisenbahn.. !.!* Hänsel und Gretel !."& Märchenbaum ## #% #% !.!# Frau Holle !."' Der Gärtner und der Fakir Python "$ !.!$ Bertram Botschafter !."( Die chinesische Nachtigall Stählerne Achterbahn mit Loopings. (Wartungsarbeiten bis 31. März 2018) "" "% " Sprookjesboom Show Carnaval Ruigrijk Plein #& Festival Plein Freilichtvorstellung mit Märchenwaldbewohnern De Vliegende Hollander #" (in Niederländisch). Geheimnisvoller Wassercoaster. H## S#" * De Sprookjessprokkelaar #' Joris en de Draak S"" "# Begegnung mit De Sprookjessprokkelaar (der Märchensammler). Zweigleisige hölzerne Racing-Achterbahn. # Diorama #( Baron CFNF ZENRI Miniaturwelt. Dive -

Arrangement De Lux 2 Overnachtingen, Incl. 1 Dag Entree

Arrangement de lux 2 overnachtingen, incl. 1 dag Entree Efteling + parkeerkaart ! Prijs 2 personen €242,00 euro Prijs 3 personen €278,00 euro Prijs 4 personen €314,00 euro *Excl. € 0,89 p.p. / p.d. Toeristen belasting. *Excl Ontbijt. (kan er los bij geboekt worden, € 7,50 p.p / p.d.) Wat is er mooier om in een sprookjes achtingen wereld als de Efteling op een rustige manier te ontdekken, na of voor een overnachting in Villa Pats. Villa Pats ligt op 15 minuten rijden afstand van de Efteling. De Efteling is een adembenemend natuurschoon en een van de meeste populaire pretparken van Europa en heeft heel veel te beiden, zoals de snelle achtbanen, met o.a. De Python, Joris en de Draak, Vogelrok, De Vliegende Hollander en de Baron 1898. Maar ook de sprookjes achtige Droomvlucht en Symbolica en de Fata Morgana, en natuurlijk niet vergeten het prachtige Sproojes bos. Ook zijn er voldoende restaurantjes voor een lekker maaltijd of om gewoon lekker wat te drinken en natuurlijk mag je de fontein show Aquanura niet missen voordat u weer terug rijd naar huis of naar Villa Pats. Tip: combineer u reis met een bezoek aan de zoo de Beekse Bergen ( 10 minuten rijden vanaf Villa Pats), of maak een stedentrip naar Breda (7 km), Tilburg (6 km), Eindhoven (42 km), den Bosch (32 km), Rotterdam (62 km) of Antwerpen (59 km) of de vele andere bezienswaardige in de omgeving: Speelboederij indoor / outdoor Vossenberg, Gilze (3 km) Kids wonderland, Molenschot (5,4 km) Oliemeulen insecten dierenpark, Tilburg (11 km) Brabants museum, den Bosch (37 km) Baarle nassau -

André Rieu in Wonderland

André Rieu in Wonderland A walk through the amusement park "Efteling" where this DVD was recorded. Version 1.4, Jun 2011 The Wonderland walk. Page 1 of 34 Introduction In the summer of 2007, André Rieu and the JSO recorded the DVD “Wonderland” in the fairytale park “Efteling” in The Netherlands. From several people we received requests for more information on this park. In this document we provide some useful information (how to get there, opening times, etc.) and a "Wonderland walk" through the park, passing by many places you will see in the “Wonderland” DVD. History of the “Efteling” Ask any Dutch person above the age of 40 about the “Efteling”. Ten to one they all give you the same answers: “the flying carpet”, “dancing red shoes”, “musical mushrooms”, the “trains” and “Long Neck”, to name a few. Below a picture of my brother and I in one of the little trains. I was about eight years old at that time (±1963). The other picture was taken recently (April 2008). I don’t know why, but it looks like those trains have shrunk quite a lot, but you still have to peddle like a madman to get around the track in a record time. And still no brakes, but good bumpers. But most important: all those popular attractions from the early days of the park are still there and in high demand! The history of the Efteling goes back to 1933, when a few people had an idea to start a sports park with a soccer field and a small playground. -

00 All Along the Watchtower.Indb

All Along The Watchtower uitkijktorens nader bekeken Dit boekje is is het resultaat van het All AlongTheWatchtower gelijknamige seminar onder bege- Sean Diederen leiding van Maarten Willems. Justin van der Eerden Het boekje bestaat uit een aantal Thomas Gerritsen essays waarin diverse aspecten Bastiaan Göttgens van de torens worden geanaly- Tim van der Grinten seerd. Daarnaast worden in de re- Tim van den Heuvel censies alle uitkijktorens met een Hendrik van den Hurk architectonische, en vooral kriti- Ruud van Middendorp sche, blik bekeken. Jeroen Verbeten De volgende studenten hebben dit Elke Verhoeven seminar gevolgd en achttien ver- Johanna van Warners schillende uitkijktorens onderzocht. Ivette Wennekes Resultaat van gelijknamig TU/e seminar 2010 voorwoord Uitkijktorens zijn maar mondjesmaat Twaalf studenten hebben zich bestudeerd en gedocumenteerd tijdens het seminar All Along The als typologisch verschijnsel1. Dat Watchtower verdiept in het fenomeen is opmerkelijk omdat ze niet alleen door een tactische bloemlezing als een boeiende historie en een onderzoeksobject te nemen. Dit boek breed verspreidingsgebied kennen, is de neerslag van die studie. Het maar ook in de hedendaagse verschaft een originele blik op de architectuurproductie betrekkelijk verrassende diversiteit in omvang, talrijk zijn. Er lijkt zelfs sprake van een aanleiding, impact, achtergrond, ‘verschijnsel’2. context, constructie, beleving en poëzie Daarnaast is juist het contrast van de torens. Achter elk object blijkt tussen de complexe relatie met bij nadere beschouwing een machine, andere typologieën en de eenvoud reclamezuil, sprookje, gedenkteken, van het (non-)programma erg landmark of experiment te schuilen. interessant. Uitkijktorens hebben Een uitkijktoren is meer dan trap met enerzijds hun wortels in functionele een platform om ver weg te kijken. -

Internetversie Plattegrond MT.Indd

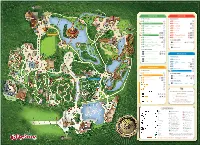

ROUTE TO EFTELING HOTEL MARERIJK RUIGRIJK ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS Sprookjesbos Kinderspoor Fairytale Tree, Once upon a time... Halve Maen Diorama D'Oude Tu er Ruigrijkplein Stoomcarrousel Polka Marina Carnaval Festivalplein Stoomtrein Stoomtrein Droomvlucht Python REIZENRIJK Raveleijn De Vliegende Hollander Villa Volta Joris en de Draak RUIGRIJK Kindervreugd FOOD AND DRINKS Volk van laaf (Monorail) Station de Oost Carrousels Anton Pieckplein SHOPS Efteling Museum Game Gallery FOOD AND DRINKS Het Wapen van Raveleijn Anton Pieckplein Het Witte Paard ANDERRIJK SHOPS ATTRACTIONS In den ouden Marskramer PandaDroom Efteling Brink Loetiek Spookslot Piraña Bob REIZENRIJK Fata Morgana Witte Paardplein ATTRACTIONS Aquanura Carnaval Festival FOOD AND DRINKS MARERIJK WACHT EN SHOWTIJDENBORD Jokie and Jet Pirañaplein Restaurant Applaus Ton Vogel Rok van de Ven Octopus plein ANDERRIJK Monsieur Cannibale FOOD AND DRINKS Avonturen Doolhof Efteldingen Kleuterhof Pagode Gondoletta FOOD AND DRINKS SHOWS AND LIVE ENTERTAINMENT Dates and times: Polles Keuken Steenbokplein Check the waiting and show time board or the Efteling app. Welkom Spieltage und zeiten: Siehe Warte- und Showzeiten-Bord oder Efteling-App. SHOPS Les jours et les heures : Herautenplein Consultez le tableau des heures d'attente et de Pardoes Promenade Jokies Wereld représentation ou l'application Efteling. BEST VIEW! Fata Morgana plein • LEGENDA • Information/park map Waiter service Information/ Parkplan Bedienung Shows & live-entertainment Gluten-free items available Informations/plan du parc Service Glutenfrei möglich Toilets Self-service Indoor attraction Egalement disponible sans gluten Toiletten Selbstbedienung Überdachte Attraktion Not accessible for disabled people Toilettes Self-service Attraction couverte Nicht barrierefrei Non accessible aux personnes Telephone Take away Open-air attraction à mobilité réduite Dwarrelplein Telefon Take away Attraktion im Freien Téléphone A emporter Attraction en plein air Min. -

Over Kwaliteit, Kitsch En Kozijntjes

Over kwaliteit, kitsch en kozijntjes Een avond bij Michel den Dulk Eftelist, 10 juli 2006 “Het zit ’m vaak in heel kleine dingen. Details die door de meeste mensen niet eens meteen worden waargenomen.” 2 Over kwaliteit, kitsch en kozijntjes - Een avond bij Michel den Dulk De herinnering aan zes maart 2005 zal de meeste Eftelingliefhebbers niet direct doen vervallen in anekdotes over aan de grond genageld staan, of de theepot pardoes uit de handen laten vallen. Maar we keken er in de vroege lente van vorig jaar allemaal wél ontzettend van op toen we hoorden dat Michel den Dulk - protégé van Ton van de Ven en ontwerper van kunststukjes als het Anton Pieckplein en het Meisje met de Zwavelstokjes - niet meer werkzaam was bij de Efteling. Veel begrepen we er niet van. De jonge creatieveling had de naam een lastpak te zijn, maar had in korte tijd al zoveel prachtigs aan het Kaatsheuvelse park toegevoegd, dat niemand het ook maar een ogenblik zag aankomen. Het had zo veilig geleken; het vertrek van Van de Ven als creatief directeur was een stuk beter te verdragen in de geruststellende wetenschap dat het stokje werd doorgegeven aan een jonge opvolger die het werken met de geleende hand van Anton Pieck in elk geval uitstekend voor elkaar kreeg, en misschien nog wel veel meer in zijn mars had. Na het vertrek van Michel den Dulk uit de Efteling lijkt het park het befaamde ‘korset van het Pieckeriaanse denken’ als een oude nachtpon op de kar van de lorrenman te hebben gegooid, jammer genoeg. -

Herinneringen Aan De Sprookjes Het Efteling-Gevoel Voor Thuis: 1

Herinneringen aan de sprookjes Het Efteling-gevoel voor thuis: 1. Pardoes-pop De paddestoel waar muziek uit 2. Aura (pluche schildpad uit PandaDroom) 3. Fotoboekje met plattegrond komt boeit al generaties lang. De 4. Pardotje-pop (neefje van Pardoes) Efteling heeft ‘iets’. De sfeer, de 5. Eftelingboek Kroniek van een Sprookje 6. Sprookjesboek Eftelingsprookjes gezelligheid en Anton Pieck. Ze (Martine Bijl) zorgen voor het alom bekende 7. Pardijntje-pop (vriendin van Par- Eftelinggevoel. does) 8. Pardoes-pop (Tovernar) door Ilze Rike 9. Mok Kleinduimpje met chocola- demelk (Winter Efteling) wereld je ook ls klein meisje kwam ik elk 10. CD met muziek uit de Efteling A komt, ik ben jaar wel een keer in de Efteling. Al een liefheb- voor we in de auto stapten zong ik Handige parktips ber en heb met mijn zusje de deuntjes van de er dus heel Ga indien mogelijk tijdens een schooldag. Dan kan het erg rustig kikkers van de Indische Waterlelies wat gezien, zijn, vooral in het najaar, omdat er dan minder schoolreisjes zijn. en later het Carnavalfestival. Bij overal heb Koop kaartjes van tevoren, bij Albert Heijn, ANWB-bespreekkan- Den Bosch dachten we dat we Lang- je bij het toor, groot postkantoor, GWK-kantoor, airmileswinkel of via internet nek konden zien. En eenmaal op (www.efteling.com) Soms is dan te profiteren van (kortings)acties. naar buiten het parkeerterrein maakten we ruzie In ieder geval voorkomt het in de rij staan voor de ingang. lopen het over waar we als eerste in zouden Koop ook direct na binnenkomst vast de parkeermunt. gevoel ‘Het gaan.Ik herinner me nog de eerste De Efteling is ingedeeld in vier ‘rijken’. -

170916 Wandelroute NL.Indd

Efteling Wandelroute Ontdek de Efteling nog beter met deze Wandelroute Laat je verrassen door de vele wonderlijke en avontuurlijke attracties! Naam: Inleiding Deze Efteling wandelroute is een wandeling langs de mooiste plekjes, attracties en diverse horecapunten van de Efteling. Ook komen leuke wetenswaardigheden en een stukje geschiedenis aan bod. Het duurt ongeveer drie uur om deze wandelroute te lopen, maar je kunt er ook de hele dag over doen. Dit is afhankelijk van je tempo en het aantal attracties dat je bezoekt. Uiteraard heb je ook alle gelegenheid om tijdens de wandeling af en toe te pauzeren voor een kopje koffie, een lunch of diner. De route begint direct bij het Huis van de Vijf Zintuigen, de hoofdentree van de Efteling. Vervolgens staat beschreven hoe je het beste kunt lopen om optimaal van het attractiepark te genieten. Veel plezier tijdens de wandeling! Entree Het Huis van de Vijf Zintuigen (de hoofdentree) is in 1996 in gebruik genomen. Voor de rieten kap zijn speciaal 800 bomen gekweekt. De hoogte van het dak is 43 meter en de oppervlakte is 4.500 m². Onder de kap broeden verschillende vogelsoorten, waaronder de bosuil. In dit indrukwekkende gebouw bevinden zich de kassa´s en de Gastenservice. Het plein dat je na de controlepoortjes op loopt heet het Dwarrelplein. Voordat je aan het einde van het Dwarrelplein het spoor oversteekt, kom je langs de watershow Aquanura. Dit is de grootste watershow van Europa en een eerbetoon aan één van de eerste sprookjes die de Efteling rijk was, namelijk De Kikkerkoning. Deze sensationele watershow is speciaal voor de viering van het 60 jarig bestaan van de Efteling gebouwd door WET design. -

Internetversie Plattegrond Zomer.Indd

EFTELING HOTEL MARERIJK RUIGRIJK S ATTRACTIES ATTRACTIES E Sprookjesbos Kinderspoor Sprookjesboom, Er was eens... Halve Maen Ruigrijk Plein Diorama D’Oude Tu er Carnaval Festival Plein S Stoomcarrousel Polka Marina S Stoomtrein Stoomtrein REIZENRIJK T Droomvlucht Python Raveleijn De Vliegende Hollander RUIGRIJK Villa Volta Joris en de Draak Kindervreugd Baron 1898 (Zomer/Summer/Sommer/ Été 2015) Volk van Laaf (Monorail) zomer/summer/Sommer/été 2015 ETEN EN DRINKEN Carrousels Anton Pieck Plein S Station de Oost Efteling Museum Anton T Pieck Plein De Kombuys ETEN EN DRINKEN A SOUVENIRS Het Wapen van Raveleijn S Efteling Brink S D Game Gallery ‘t Po ertje D F F Het Witte Paard B ANDERRIJK SOUVENIRS Witte Paard Plein S ATTRACTIES In den Ouden Marskramer WACHT EN SHOWTIJDENBORD WAITING AND SHOW TIME BOARD S WARTE UND SHOWZEITENTAFEL PANNEAU DE TEMPS D’ATTENTE ET D’HEURES DE SPECTACLE S PandaDroom Loetiek WACHT EN SHOWTIJDENBORD Piraña Plein MARERIJK WAITING AND SHOW TIME BOARD WARTE UND SHOWZEITENTAFEL PANNEAU DE TEMPS D’ATTENTE ET D’HEURES DE SPECTACLE Spookslot Ton van de Ven Plein ANDERRIJK Piraña A REIZENRIJK Bob ATTRACTIES Fata Morgana Carnaval Festival Aquanura Jokie en Jet ETEN EN DRINKEN H Vogel Rok Steenbok C Plein Restaurant Applaus Monsieur Cannibale X H Octopus Avonturen Doolhof Pardoes Promenade X De Steenbok Herauten Plein Kleuterhof KIJKTIP Fata Morgana Pagode Plein SOUVENIRS Gondoletta S De Bazaar S S Efteldingen ETEN EN DRINKEN B Polles Keuken Dwarrel -

Usage Case and Initial Exploitation Scenarios That Are Later Used in D1.3 for Identifying Relevant Generic Functions, Kpis and System Architecture

Ref. Ares(2015)1164079 - 17/03/2015 D1.1 Usage case and Exploitation Scenarios Project Acronym: WATERNOMICS Project Title: ICT for Water Resource Management Project Number: 619660 Instrument: Collaborative project Thematic Priority: FP7-ICT-2013.11 © WATERNOMICS consortium Page 1 of 129 D1.1 Work Package: WP1 Due Date: 31/01/2015 Submission Date: 31/01/2015 Start Date of Project: 01/02/2014 Duration of Project: 36 Months Organisation Responsible of Deliverable: NUIG Version: 1.7 Status: Draft Author name(s): Sander Smit BM-Change Daniel Coakley NUIG Eoghan Clifford NUIG Wassim Derguech NUIG Thomas Messervey R2M Christos Kouroupetroglou U4 Edward Curry NUIG Riccardo Puglisi R2M Reviewer(s): Thomas Messervey R2M Edward Curry NUIG Eoghan Clifford NUIG Nature: R – Report P – Prototype D – Demonstrator O – Other Dissemination level: PU – Public CO – Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission) RE – Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme (2007-2013) © WATERNOMICS consortium Page 2 of 129 619660 Revision history Version Date Modified by Comments 0.1 19/05/14 Edward Curry Initial Version of Document 0.2 02/06/14 Sander Smit Added methodology 0.3 11/07/14 Sander Smit Added input from interviews 0.4 19/07/14 Daniel Coakley Added Public users (Scholars and students) Scenario 0.5 21/07/14 Sander Smit Added Business Strategies 0.6 22/07/14 Sander Smit Added ranked feature list 0.6_THM 24/07/14