Volume 10, No. 2 May 2018 Special Feature: 'Voices from the Margins'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Baxter, Katherine and Smith, Lytton (2016) Writing in Translation: Robert Sullivan’s 'Star Waka' and Craig Santos Perez’s 'from unincorporated territory'. Literary Geographies, 2 (2). pp. 263-283. ISSN 2397-1797 Published by: Literary Geographies URL: http://www.literarygeographies.net/index.php/LitGe... <http://www.literarygeographies.net/index.php/LitGeogs/article/view/55> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/28810/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published -

Ka Mate Ka Ora: a New Zealand Journal of Poetry and Poetics

ka mate ka ora: a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics Issue 4 September 2007 Poetry at Auckland University Press Elizabeth Caffin Weathers on this shore want sorts of words. (Kendrick Smithyman, ‘Site’) Auckland University Press might never have been a publisher of poetry were it not for Kendrick Smithyman. It was his decision. As Dennis McEldowney recalls, a letter from Smithyman on 31 March 1967 offering the manuscript of Flying to Palmerston, pointed out that ‘it is to the university presses the responsibility is falling for publishing poetry. Pigheaded and inclined to the parish pump, I would rather have it appear in New Zealand if it appears anywhere’.1 Dennis, who became Editor of University Publications in 1966 and in the next two decades created a small but perfectly formed university press, claimed he lacked confidence in judging poetry. But Kendrick and C. K. Stead, poets and academics both, became his advisors and he very quickly established an impressive list. At its core were the great New Zealand modernist poets. Dennis published five books by Smithyman, three by Stead and three by Curnow starting with the marvellous An Incorrigible Music in 1979.2 Curnow and Smithyman were not young and had published extensively elsewhere but most would agree that their greatest work was written in their later years; and AUP published it. Soon a further group of established poets was added: three books by Elizabeth Smither, one by Albert Wendt, one by Kevin Ireland. And then a new generation, the exuberant poets of the 1960s and 1970s such as Ian Wedde (four books), Bill Manhire, Bob Orr, Keri Hulme, Graham Lindsay, Michael Harlow. -

Indigenous Transnational Visibilities and Identities in Oceania Establishing Alternative Geographies Across Boundaries

Université de Montréal Indigenous Transnational Visibilities and Identities in Oceania Establishing Alternative Geographies across Boundaries Par Coline Souilhol Département de littératures et de langues du monde Arts et Sciences Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de maîtrise en études anglaises Juin 2020 © Coline Souilhol, 2020 Université de Montréal Département de littératures et de langues du monde Faculté des arts et des sciences Ce mémoire intitulé Indigenous Transnational Visibilities and Identities in Oceania Establishing Alternative Geographies across Boundaries Présenté par Coline Souilhol A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes Heather Meek Membre du jury Sarah Henzi Membre du jury Heike Harting Membre du jury 1 Résumé Pendant la deuxième moitié du vingtième siècle, les régions du Pacifique, et notamment l’Australie et la Nouvelle-Zélande, ont vu augmenter les mouvements de migrations. Ces derniers ont permis une diversification des concepts de nationalité, d’identité, de langage et d’espace. De ce fait, bon nombre d’auteurs ont donc décidé d’approcher leurs écrits à travers le spectre du transnationalisme et ont cherché à repousser les limites culturelles et les frontières géographiques -imposées par un état colonial.- Par conséquent, c’est avec une approche comparative que j’analyserai, en tenant ainsi compte de la constante évolution des nouveaux cadres géographiques et culturels, le recueil de poèmes Star Waka (1999) de l’auteur maori Robert Sullivan, le roman graphique Night Fisher (2005) de l’artiste hawaiien R. Kikuo Johnson et le roman Carpentaria de l’autrice waanyi Alexis Wright. En effet, j’examinerai la formation des identités autochtones en lien avec le lieu natal respectif de chaque auteur tout en tenant compte de l’évolution de la notion de frontière, qu’elle soit locale ou nationale. -

Looking for Truthiness

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research or private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the author. i Looking for Truthiness A personal investigation into bicultural poetry from the Bay of Islands presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Creative Writing at Massey University, Albany New Zealand. Shelley Marie Arlidge 2020 ii Abstract The creative component of this thesis mixes poems, prose poems and prose. Boundaries are blurred. English and Te Reo Māori intermingle and sit side by side, as do memoir and writing situated in the present. Time is sometimes curved and loved ones are brought back. Parts of the portfolio touch on environmental issues. The main recurring theme is a search, not only for ‘truthiness’ which may help the author find a comfortable place to stand, but also for physical, intellectual and emotional nourishment from food, nature, family, community and place. The critical component is an exegesis, which looks at influences on this writing, influences which are both local and international, male and female, Māori and Pākehā. A research question is explored in the exegesis – What are the social, historical and personal constraints and drivers behind the work presented and considered here? Particular attention is given to the consequences of colonisation in Aotearoa-New Zealand, with a focus on writing from the greater Bay of Islands area by Robert Sullivan and Glenn Colquhoun. Although three decades have passed since their first books were published, many of the issues their writing explored remain unresolved. -

Contributors

Contributors serie (cherie) barford was born in Aotearoa to a Samoan-born mother (Stunzner/Betham/Leaega of Lotofaga and Fulu / Jamieson of Luatuanu‘u) and a pëlagi father. Her latest book, Tapa Talk, was published in 2007, and her works have appeared in multidisciplinary books, journals, and Web sites. keith l camacho is a Chamorro writer from the Mariana Islands and a former creative writing student of Albert Wendt. Currently, he is an assistant professor in the Asian American Studies Department at the University of Cali- fornia, Los Angeles. His book Cultures of Commemoration: The Politics of War, Memory, and History in the Mariana Islands is forthcoming from the University of Hawai‘i Press in the Pacific Islands Monograph Series. david chappell is associate professor of Pacific Islands history at the Uni- versity of Hawai‘i at Mënoa. For more than a decade, he has been focusing his studies on the French Pacific territories, especially Kanaky New Caledonia. sia figiel, internationally acclaimed Samoan author of Where We Once Belonged (1996), has had her work translated into at least eight languages. Author of two novels, a novella, a collection of poetry, and a collaborative spoken-word cd, she works and lives with her sons in American Sëmoa. jon fraenkel is a senior research fellow with the State, Society, and Gover- nance in Melanesia Program at the Australian National University. He previ- ously worked for eleven years at the University of the South Pacific in Fiji. He specializes in Pacific electoral systems, political science, and economic history. april k henderson is a lecturer in Pacific studies at Victoria University of Wellington. -

Reviews Contents

TEXT Vol 19 No 1 (April 2015) Reviews contents • Craig Batty (ed), Screenwriters and Screenwriting: Putting practice into context review by Felicity Packard page 2 • Patrick West and Om Prakash Dwivedi (eds), The World to Come review by Nike Sulway page 5 • Moya Costello, Harriet Chandler: A novella review by Julienne van Loon page 8 • Keith St Clair Butler, The Secret Vindaloo review by Dominique Hecq page 12 • Reina Whaitiri, Robert Sullivan (eds), Puna Wai Kōrero: An Anthology of Māori Poetry in English review by Jörg-Dieter Riemenschneider page 15 • Geoff Goodfellow, Opening the Windows to Catch the Sea Breeze: Selected poems 1983-2011 review by SK Kelen page 21 • Dominique Hecq, Stretchmarks of Sun review by Vivienne Plumb page 24 • Susan Bradley Smith, Beds for All Who Come review by Susie Utting page 27 • Anne Elvey, Kin review by Jessica L. Wilkinson page 30 • Bel Schenk, Every Time You Close Your Eyes review by Linda Weste page 34 • Grant Caldwell, Love & Derangement review by Jeremy Fisher page 38 • Lisa Jacobson, South in the World review by Amy Brown page 41 • Michelle Leber, The Yellow Emperor: A Mythography in Verse review by Ruby Todd page 44 Review of Craig Batty (ed), Screenwriters and Screenwriting TEXT Vol 19 No 1 TEXT review Illuminating the screenplay review by Felicity Packard Screenwriters and Screenwriting: putting practice into context Craig Batty (ed) Palgrave Macmillan, Houndsmill Basingstoke 2014 ISBN 9781137338921 Hb 320pp GBP60.00, AUD207.75 In his introduction to Screenwriters and Screenwriting: putting practice into context, editor Craig Batty expresses his frustration at the snobbery with which academia has tended view the many ‘how to’ guides to screenwriting: …for a field whose central concern is practice – the screenwriter writes and the screenplay is written for production – I find it somewhat disappointing that many academics quickly write off anything intended to aid writing practice. -

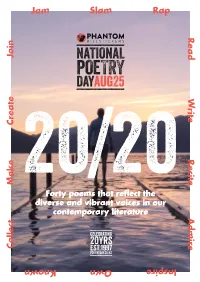

Jam Inspire Create Join Make Collect Slam Own Rap Known Read W Rite

Jam Slam Rap Read Join Write Create Recite Make 20/20 Forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant voices in our contemporary literature Admire Collect Inspire Known Own 20 ACCLAIMED KIWI POETS - 1 OF THEIR OWN POEMS + 1 WORK OF ANOTHER POET To mark the 20th anniversary of Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day, we asked 20 acclaimed Kiwi poets to choose one of their own poems – a work that spoke to New Zealand now. They were also asked to select a poem by another poet they saw as essential reading in 2017. The result is the 20/20 Collection, a selection of forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant range of voices in New Zealand’s contemporary literature. Published in 2017 by The New Zealand Book Awards Trust www.nzbookawards.nz Copyright in the poems remains with the poets and publishers as detailed, and they may not be reproduced without their prior permission. Concept design: Unsworth Shepherd Typesetting: Sarah Elworthy Project co-ordinator: Harley Hern Cover image: Tyler Lastovich on Unsplash (Flooded Jetty) National Poetry Day has been running continuously since 1997 and is celebrated on the last Friday in August. It is administered by the New Zealand Book Awards Trust, and for the past two years has benefited from the wonderful support of street poster company Phantom Billstickers. PAULA GREEN PAGE 20 APIRANA TAYLOR PAGE 17 JENNY BORNHOLDT PAGE 16 Paula Green is a poet, reviewer, anthologist, VINCENT O’SULLIVAN PAGE 22 Apirana Taylor is from the Ngati Porou, Te Whanau a Apanui, and Ngati Ruanui tribes, and also Pakeha Jenny Bornholdt was born in Lower Hutt in 1960 children’s author, book-award judge and blogger. -

Puna-Wai-Korero Sample.Pdf

In this pioneering anthology, two leading Māori poets INTRODUCTION and scholars collect together many Māori voices in English and let flow a wellspring of poetry. Whakapapa is the fulcrum around which Māori construct iwi histories. It is also the source from which we draw inspiration. Everyone and everything, including poetry, From revered established writers as well as exciting new voices, the has whakapapa, and the kaupapa of Puna Wai Kōrero is to explore the one hundred poems in Puna Wai Kōrero offer a broad picture of Māori poetry in or so years of poetry written in English by Māori. As far as we have discovered, the English. The voices are many and diverse: confident, angry, traditional, earliest poem published in English was written by Apirana Ngata, so it is him that respectful, experimental, despairing and full of hope, expressing a all subsequent Māori poets writing in English whakapapa back to. range of poetic techniques and the full scope of what it is to be Māori. Sir Apirana Ngata was a true visionary and his mauri lives on in the people and in his work. It was Ngata who collated hundreds of annotated songs in te reo ran- The anthology collects work from the many iwi and hapū of Aotearoa gatira, culminating in the pre-eminent anthology Ngā Mōteatea. This is the most as well as Māori living in Australia and around the world, featuring important collection of Māori-language song poems ever published and was com- the work of Hone Tuwhare, J. C. Sturm, Trixie Te Arama Menzies, pleted after his death by noted scholars, translators and linguists, including Pei Te Keri Hulme, Apirana Taylor, Roma Pōtiki, Hinemoana Baker, Tracey Hurinui Jones, Tamati Muturangi Reedy and Hirini Moko Mead. -

Here in Puna Wai Kōrero Is but Robert Sullivan (Ngāpuhi) and Reina Whaitiri (Kāi Tahu) Are the a Fraction of What Has Been Produced Over the Years

In this pioneering anthology, two leading Māori poets INTRODUCTION and scholars collect together many Māori voices in English and let flow a wellspring of poetry. Whakapapa is the fulcrum around which Māori construct iwi histories. It is also the source from which we draw inspiration. Everyone and everything, including poetry, From revered established writers as well as exciting new voices, the has whakapapa, and the kaupapa of Puna Wai Kōrero is to explore the one hundred poems in Puna Wai Kōrero offer a broad picture of Māori poetry in or so years of poetry written in English by Māori. As far as we have discovered, the English. The voices are many and diverse: confident, angry, traditional, earliest poem published in English was written by Apirana Ngata, so it is him that respectful, experimental, despairing and full of hope, expressing a all subsequent Māori poets writing in English whakapapa back to. range of poetic techniques and the full scope of what it is to be Māori. Sir Apirana Ngata was a true visionary and his mauri lives on in the people and in his work. It was Ngata who collated hundreds of annotated songs in te reo ran- The anthology collects work from the many iwi and hapū of Aotearoa gatira, culminating in the pre-eminent anthology Ngā Mōteatea. This is the most as well as Māori living in Australia and around the world, featuring important collection of Māori-language song poems ever published and was com- the work of Hone Tuwhare, J. C. Sturm, Trixie Te Arama Menzies, pleted after his death by noted scholars, translators and linguists, including Pei Te Keri Hulme, Apirana Taylor, Roma Pōtiki, Hinemoana Baker, Tracey Hurinui Jones, Tamati Muturangi Reedy and Hirini Moko Mead. -

A History of New Zealand Literature Mark Williams Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-08535-0 - A History of New Zealand Literature Mark Williams Frontmatter More information A HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE A History of New Zealand Literature traces the genealogy of New Zealand literature from its fi rst imaginings by colonial Europeans to the development of a national canon in the twentieth century. Beginning with a comprehensive introduction that charts the growth of a national literary tradition, this History includes exten- sive essays that illuminate the cultural and political intricacies of New Zealand literature. Organized thematically, these essays survey the multilayered verse, fi ction, and drama of such diverse writers as Katherine Mansfi eld, Allen Curnow, Frank Sargeson, Janet Frame, Keri Hulme, Witi Ihimaera, and Patricia Grace. Written by a host of leading scholars, this History devotes special attention to the lasting signifi cance of colonialism, the Māori Renaissance, and multicul- turalism in New Zealand literature. Th is book is of pivotal impor- tance to the development of New Zealand writing and will serve as an invaluable reference for specialists and students alike. Mark Williams is Professor of English at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand. He is the author of Leaving the Highway: Six Contemporary New Zealand Novelists , Patrick White , and with Jane Staff ord, Maoriland: New Zealand Literature 1872–1914 . Williams has also coedited Th e Auckland University Press Anthology of New Zealand Literature with Jane Staff ord. © in this web service Cambridge -

Albert Wendt's Critical and Creative Legacy in Oceania

Albert Wendt’s Critical and Creative Legacy in Oceania: An Introduction Teresia Teaiwa and Selina Tusitala Marsh The Flyingfox has faced the dark side of the moon and knows the gift of loneliness The stars have talked to him of ice He has steered the sea’s secrets to Aotearoa Fiji Hawaii Samoa and gathered the spells of the albino atua He has turned his blood into earth and planted mischievous aitu in it His is the wisdom of upsidedownness and the light that is Pouliuli (Albert Wendt, “For Kauraka”) (the dark side of the moon) We find ourselves at a moment of witnessing both the retirement, in a pro- fessional sense, and the inevitable passing away of many who constituted the first substantial wave of Pacific academics, intellectuals, and contem- porary artists. Although this collection was planned and initiated several years ago, we have been finalizing it in the shadow of mourning such formidable Pacific patriarchs as poet and activist Hone Tuwhare; scholar, writer, and arts patron Epeli Hau‘ofa; researcher and publisher Ron Cro- combe; poet and writer Alistair Te Ariki Campbell; and philosopher and educator Futa Helu. The contributors to this issue have in various permu- tations been part of conversations taking place in and around Oceania, about what the first wave—that first full generation of conscious, consci- entious Oceanians—has bequeathed to the generations who follow them. The contributions contained here thus document a process of deliberate reckoning with a unique intellectual inheritance. The Contemporary Paci²c, Volume 22, Number 2, 233–248 © 2010 by University of Hawai‘i Press 233 234 the contemporary pacific • 22:2 (2010) This special issue focuses on one of our predecessors and elders, Albert Wendt. -

Ocean of Stars: Albert Wendt and Pacific Literature in English

Kunapipi Volume 26 Issue 2 Article 16 2004 Ocean of stars: Albert Wendt and pacific literature in english Dieter Riemenschneider Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Riemenschneider, Dieter, Ocean of stars: Albert Wendt and pacific literature in english, Kunapipi, 26(2), 2004. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol26/iss2/16 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Ocean of stars: Albert Wendt and pacific literature in english Abstract Paul Sharrad’s recently released book on Albert Wendt, the first monograph on the outstanding literary figure of the Pacific egion,r is not only an ambitious but a profoundly successful scholarly study that deserves our attention. It enters the critical discourse on the ‘new’ literatures in English as a timely reminder of the importance of a regional literature and of Wendt’s literary and critical contribution to this discourse, both widely neglected among critics from beyond the Pacific. This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol26/iss2/16 159 DIETER RIEMENSCHNEIDER Ocean of Stars: Albert Wendt and Pacific Literature in English Paul Sharrad’s recently released book on Albert Wendt, the first monograph on the outstanding literary figure of the Pacific region, is not only an ambitious but a profoundly successful scholarly study that deserves our attention. It enters the critical discourse on the ‘new’ literatures in English as a timely reminder of the importance of a regional literature and of Wendt’s literary and critical contribution to this discourse, both widely neglected among critics from beyond the Pacific.